Chiushingura (1880)/Appendix

Appendix.

here are several different texts of the Chiushingura extant, among which that of the jôruri,[1] which has been chiefly used in preparing the foregoing translation, seems to be the most popular.

here are several different texts of the Chiushingura extant, among which that of the jôruri,[1] which has been chiefly used in preparing the foregoing translation, seems to be the most popular.

The most complete and standard text, however, is that of the “Yehon Chiushingura” (Illustrated Chiushingura), in two parts, each ten volumes, the first part narrating the events that led up to the conspiracy of the forty-seven rônin, and the successful issue of it; the latter part the further fortunes of the conspirators. The work is profusely illustrated with spirited though coarsely-executed woodcuts, and seems to have been published in the twelfth year of the “nengo” Kuwansei (A.D. 1800–1). It is extremely badly printed, and little use has been made of it in preparing the present translation.

The author was one Chikamatsu Monzayemon, who appears to have flourished in the early portion of the eighteenth century. I am not aware of any other important production of his pen.

The edition I have principally used[2] announces itself as having been printed, partly at Ohosaka, by one Seisuke, at the sign of Kajima, in the Funa-machi (“Ship Street”); partly at Yedo, at a house in the Seto-mono-chô (“Porcelain Street”), near the Nihon-bashi (“Japan Bridge”—the “London Bridge” of the Capital of Dai Nippon).

It is in eleven parts or livraisons, the last being double, and is printed in a large thick character known as kantera, a term apparently not Japanese, and the meaning of which I have been unable to discover.

The text is written partly in sôsho,[3] Chinese character, partly in the flowing Japanese syllabic character known as hiragana, the sôsho forms being not seldom accompanied by a transliteration into hiragana.

In addition, the columns of the text are, to some extent, notated musically; various marks indicating where and how the voice should be modulated, and where the accompaniment should be introduced. There is no punctuation, beyond a division into sentences or phrases, shown by a plain circle having nearly the same value as our comma.

A Japanese orchestra generally consists of nine performers (gakunin), distributed as follows:

- Two Taiko-gata, or drummers.

- Two Fuye-gata, or fife-players.

- Two Shoshichiriki, or flageolet-players.

- One Kane-gata, answering to our triangle-man.

- Two Utai-gata, or song-men.

Such an orchestra is called a kunin-bayashi; when it consists of only one performer of each kind it is called a gonin-bayashi—i.e., “five-men-grove” hayashi, “grove” being the technical term for a musical band, company, or orchestra. The kane-gata generally introduces and terminates the whole piece, and each successive movement of the music as well. He is followed by the flageolet-players, and they, in their turn, by the lifers, the drummers coming last. The whole band, except the kane-gata and the utai-gata, then perform a sextet in concert, the kane-gata introducing his instrument from time to time. The sextet finished, the duets—or, in a gonin-bayashi, the solos—recommence, and the whole piece thus consists of a succession of movements, in which the instrumentalists follow each other in the order above described; each movement being a series of duets, in a full orchestra, by the different musicians, followed by a sextet of the whole of them, except the triangle and song-men.

The action of the romance is laid in the 14th century, but the events upon which it is founded really occurred at the commencement of the 18th; and must have created a great and lasting interest among the people, for the story is referred to in the commonest epitomes of Japanese history, and is—or, at least, was, some few years ago—familiar to every Japanese with the least tincture of education. In view, however, of the severe penalties that, under the Shôgunate, attached to the publication of recent or current events of a public character, the author found himself forced to adopt the practice, not uncommon with Western writers of a couple of centuries back, of barely disguising the reality by diluting it, so to speak, with a certain amount of fiction, and by so altering names and dates as to evade the law without too effectually concealing the truth. The episode has been given to the world by Mr. Mitford, in one of his admirable Tales of Old Japan, that of the “Forty-seven Rônin”; but I have nevertheless thought it not out of place to re-tell the tale in the following abbreviation from a popular Japanese version of it, endeavouring as far as possible merely to supply the lacunæ in Mr. Mitford’s version.

During the reign of the Shôgun Iyetsuna, the President of the Gorôjiu (Council of State, lit., “August Assembly of Elders”), about the middle of the 11th month of the 13th year of the period Genroku (A.D. 1701), was officially informed that, in the 3rd month of the ensuing year, three ambassadors of high rank would arrive at Yedo from the Court at Kiyôto. The President, in consequence of this announcement, appointed Asano Takumi-no-Kami (Yenya Hanguwan) and Kamei Sama (Wakasanosuke) special commissioners to receive the ambassadors, with directions to consider themselves under the orders of an official of no very high rank, Kira Kôdskenoske Yoshifusa (Moronaho). The Karô of Kamei, Ogiwara (Honzô) by name, on hearing of his master’s appointment under Kira Kôdske, who soon began to show his harsh and tyrannical disposition, lost no time in seeking out the latter, and winning his favour by timely gifts. Ohoishi Kuranosuke (Ohoboshi Yuranosuke), the Karô of Asano Takumi, refused to act in a similar manner, though much passed to do so by Ohotaka Gengo (Ohowashi Bungo), a retainer of Asano. Kira Kôdske consequently received Asano with the worst grace possible, and took every opportunity of slighting him. On the arrival of the ambassadors, Asano, who was but ill-acquainted with the duties of his office, committed several grave errors in the discharge of his commission, for which he was severely reprimanded by Kira Kôdske. Anxious to avoid a repetition of his fault, Asano, previously to the coming-off of a grand entertainment which the Court at Yedo gave to the ambassadors, sought advice and instruction from his superior. But the revengeful and covetous Kira Kôdske refused to assist him in any way, and treated him with such violence that the unfortunate Asano at last lost his temper, and drew his sword upon his tyrant within the precincts of the palace, inflicting upon him a severe wound. Kira Kôdske, indeed, would have been slain, but for the timely, or untimely, interference of one Kachikawa Yosobei (whose rôle, in the romance, is appropriated by Honzô). By thus drawing weapon within the court-precincts, Asano committed a capital offence, and was accordingly compelled to rip his bowels open, on the 14th of 3rd month of 14th year of Genroku (A.D. 1702).

Meanwhile, Kayano Sampei (Hayano Kampei), a retainer of Asano, in company with a comrade, had, at the commencement of the quarrel between their master and Kira Kôdske, the consequences of which he dreaded, travelled the extraordinary distance of 170 ri (420 miles) in 4¼ days—ordinarily a journey of 17 days—to find the Karô of their clan, Kuranosuke, who was in Banshiu (Harima), and warn him of the danger which Asano ran through the ill-will of Kira Kôdske.

News of the self-dispatch arrived the very day after their arrival, and the retainers of Asano, wild with rage and grief, hardly knew how to act. Kuranosuke next received information from Yedo that, unless his master’s castle and lands were surrendered, orders would be issued that the whole family and clan of Asano should be utterly destroyed. The Karô endeavoured to avert this disaster, but in vain; and, on the news of his want of success reaching him, assembled the clan, and after explaining to them their position, and the impossibility of defending their lord’s castle and lands against his enemies, produced a document binding them to commit self-dispatch, to the terms of which he prevailed upon sixty-three of them to signify their assent in the most solemn manner, namely, by imposing upon it their hands smeared with their own blood. The rest had discreetly retired during the delivery of the Karô’s address.

Having thus separated his wheat from the chaff, he called the sixty-three together again, and told them that his real purpose was, not that they should at once commit self-dispatch, but that they should first of all slay Kira Kôdske, and afterwards “follow their lord upon the dark path.” This was agreed to on the 11th of the 4th month.

Amano Yarihei (Amagawa Gihei) now comes upon the scene. He had acted as agent for the clan, and, on hearing of the cruel death of Asano, had offered Kuranosuke all the aid he could give towards the carrying out of any design the Karô might entertain against Kira Kôdske. The Karô at first declined the trader’s assistance, but, on the latter’s devotion being shown by his attempt to kill himself on being refused the boon he asked for, Kuranosuke revealed to him the plot to revenge the death of Asano upon his enemy, and consented to allow the delighted chônin to furnish the requisite arms and fighting gear.

The Karô then laid hands on the treasure of Asano, and, after calling in and paying off the paper currency of the clan, and reserving a small sum for the expenses of the conspiracy, divided the remainder equally among his sixty-three fellow-conspirators, each of whom received 25 riyô. This was especially displeasing to one Ono Kurohei (Ono Kudaiu), who had urged the Karô to divide the money among the conspirators proportionately to their salaries—a proposition to which Kuranosuke would not listen, saying that misfortune had put them all on a level.

The conspirators then separated, promising to assemble upon the signal of the Karô.

Kayano Sampei (Hayano Kampei), meanwhile, went to his village, and there found his mother dead. His father besought him to secede from the conspiracy, pleading his age and loneliness; and Kayano, distracted between his love for his father and his sense of honour and loyalty to his lord, sought escape from the dilemma in self-dispatch.

All proper preparations having been made, Kuranosuke, with his comrades—the conspirators had, in the interval, dwindled down to forty-seven in number—forced their way into the mansion of Kira Kôdske by night, and put the enemy of their much-mourned lord to death. This act of vengeance seems to have been accomplished on the 14th of the last month of the 14th year of Genroku (A.D. 1702). The authorities were somewhat perplexed how to act—so great was the sympathy felt for the devoted band—but finally condemned them to Seppuku, which they accomplished the following year at the tomb of Asano, in the burial-ground of the Temple of Sengaku at Yedo.

The Temple of Sengaku is close to that of Tôsen, formerly the British Legation—and the tombs of Asano and his forty-seven devoted followers are still shown there.

The marvellous portion of this “ower-true tale” remains to be told. The conspirators, after slaying Kira Kôdske, cut off his head, and offered it with proper ceremonial at the tomb of their lord. As the head touched the stone-work the monument was distinctly seen to quiver.

The following is said to be the “Schwanenlied” of Asano:

Kaze sasou

Hana yori mo,

Nawo mata haru no

Nagori wo

Ika ni to ka sen!

which may be thus rendered—

Tender blossoms strew the ground,

Flung in wan confusion round

By the wind’s too boist’rous breath;

More my lot might pity find,

Forced to leave sweet Spring behind,

Doomed to an untimely death.[4]

Page 1. Shôgun.

This, the ordinary official title of the former Kubô (known generally to foreigners as Tycoon), is a Sinico-Japanese compound, meaning “General” or “Commander of the Forces.”

The full title is Sei-i-tai-shôgun, “barbarian-quelling Generalissimo,” and is said to have been first bestowed, about 86 B.C., by the Emperor Shiujin upon his son, the celebrated Yamato-dake-no-Mikoto, who reduced the indigenous Aino tribes of the North and East into subjection to the Imperial power.

The first of the hereditary Shôguns, however, was Minamoto Yoritomo, upon whom the title was conferred in A.D. 1190, or, at least, from that date, if, as some writers maintain, it was bestowed posthumously. Whatever may be the truth as to the date of bestowal of the rank upon Yoritomo, there can be no doubt as to his exercise of the power belonging to it for many years previous to his death, which was caused by a fall from his horse in the last year of the 12th century after Christ. The predominant position which he had won for the office was maintained by his successors in it, all of whom were direct or collateral descendants from the Minamoto stock—or were adopted as such—up to the year 1868, when the Mikado resumed the power of which his ancestors had for so long a period been deprived, and H’totsubashi, better known as Keiki, the last, and apparently the least energetic of his dynasty, retired to the town of Shidzuoka, some 60 miles westward of Yokohama, where, forgetful of the glories of his foregoers, he leads a life of somewhat ignoble obscurity and ease.

Page 1. The Shôgun of the Ashikaga family had overthrown Nitta Yoshisada.

The Ashikaga branch of the Minamoto family held the Shôgunate from A.D. 1334 to A.D. 1579, or thereabouts.

When the dynasty of Yoritomo became extinct, in A.D. 1219, the Shôgunate passed, nominally, first into the hands of members of the great Fujiwara house (one of the original eight noble families), and afterwards into those of a succession of Shinwô, or princes of the Imperial blood, but the real power was exercised by the Hôjô family,[5] connected by marriage, and, probably by blood also, with that of Yoritomo.

During this period, the Mikados seem to have been mere puppets in the hands of the Hôjô usurpers, but towards its close, the Emperor Godaigo—who owed his elevation to the influence of the Court of Kamakura (then the Eastern Capital and residence of the Shôguns—as Yedo, now Tôkiô, was afterwards—now a mere village, distant some 16 miles from Yokohama, and chiefly famous for its grand bronze image of Buddha)—nevertheless made a show of independence, and, in his attempt to free himself from the thraldom in which he was held by his powerful vassal, brought about the war known in Japanese history as the war between the Faction of the North (the Kamakura party) and the Faction of the South (Kiyôto party), which was to be alike ruinous to himself and his rebellious subject. The war, which commenced in A.D. 1319, lasted, or rather languished, for 75 years. During it, either party maintained its own Emperor, but since the revolution of 1868 the names of the Emperors of the North have been expunged from the Imperial catalogue, and the Emperors of the South alone are now considered as having been the rightful occupants of the throne.

In A.D. 1330, the Emperor Godaigo was taken prisoner and sent in exile to the island of Oki. A year or two afterwards, however, one of the Imperial generals defeated the Hôjô forces in a great battle, and made himself master of Kamakura. The Imperial exile was re-established upon the throne, but ungratefully gave his confidence, not to the men to whose exertions he owed his return to power, but to a member of the Ashikaga family of the name of Takauji. Disgusted with their treatment, Nitta and his party rose in rebellion against an emperor who knew so little how to requite their services. The struggle was a brief one. Takauji was ordered to march against them, and they were defeated with great slaughter, Nitta himself being among the slain. The rebellion thus extinguished, Takauji was installed as Shôgun at Kamakura, and founded a dynasty that for the next two centuries and a half was virtually to govern Dai Nippon.

Page 1. Shrine to be erected to Hachiman.

The etymology or real signification of this appellation of the Japanese Ares I have not been able to trace. The Chinese characters by which it is usually represented mean the “Eight banners,” and may possibly imply some notion of the god being a sort of manifestation of the Buddha of the Eight Banners.

The hero deified under this title was the Emperor Ôjin, who died about the commencement of the 4th century of our era. His mother was the Empress Jingu, celebrated as the conqueror of Korea. According to some, Ôjin was the conqueror of Korea, and was, on this account, deified as the God of War. Others, again, assert that he made the Japanese acquainted with the art of weaving, and favoured the adoption of Chinese civilization. He was commonly worshipped by samurahi, and was vernacularly known as the Yumiya, or Archer God. The principal temple at Kamakura is dedicated to his worship.

Page 1. Nengo Riyakuô.

Previously to the adoption, some two or three years since, of the European calendar, three systems of chronology existed in Japan, all similar in character to what still exist in China.

The era of the first commenced with the accession of the traditional Emperor Jinmu, in B.C. 600. Thus A.D. 1870 was 2530 of the era of Jinmu.

The second was based upon the sexagenal cycle used in China to the present day. The first of these cycles commenced with the 61st year of the reign of Hwang Ti, B.C. 2637, and the year 1875 is the 11th of the 76th cycle.

The mode in which the sexagenal cycle was used, and each year of it distinguished, was not a little complicated, and for an explanation of it—which would be out of place here—the reader is referred to any work of repute upon China or Japan.

According to the third system, the one most commonly used in books, any year after A.D. 645 was known by its place in the “nengo” (chin “nien hao”) or year periods, which from time to time were established and named by Imperial decree. These “nengo” had a duration of from 2 to 15 or 20 years, and were distinguished by such high-sounding titles as “Exalted Virtue,” “Celestial Peace,” “Great Development,” and the like. The present “nengo,” which is not to be changed during the life of the reigning Emperor, is called Meiji, “Illustrious Rule,” and the year 1879 is the 12th year of it.

The name “Riyakuô” in the text signifies “Uninterrupted Prosperity.”

Page 2. Wakasanosuke Yasuchika.

In Japan, the family name, only used by men, comes first; the individual name assumed at puberty comes afterwards. Under the old regime, the son of a samurahi on attaining the age of 15 performed “gembuku,” that is, shaved off his forelock, and became a “jak’k’wan,” entitled to wear a hat or cap. At the same time he adopted a “nanori,” or individual name, generally selected for him, according to certain very intricate rules, by a man of learning, with or without the assistance of a soothsayer, astrologer, or diviner.

Government officials, and shizoku generally (the samurahi of the “Tokugawa jibun,” or old Tycoon days), are now giving up the practice of “gembuku,” and wear their hair in the European fashion, as they clothe their bodies in strange-looking travesties of European garments.

Page 2. A Baron of Hakushiu.

Hakushiu is synonymous with Hôki, one of the former Sanindô provinces.[6]

Page 2. Seiwa family, a Genji house.

The usurpation of Yoritomo—for such, in effect, his ascendancy became—towards the close of the 12th century, was the culminating point of the struggle between the powerful Taira, or Hei, and the Minamoto, or Gen, clans, that for a long course of years had spread ruin through the Empire, to end in the establishment of the hereditary Shôgunate in the family of the successful chief of the latter faction. The Seiwa was the elder branch of the Gen house, and derived its name from its founder, the Emperor Seiwa, who flourished about the middle of the 9th century.

Page 2. Feudatories.

In the text “Hatamoto,” literally, “under the flag” (of the Shôgun). They were the lesser feudatories of the Kubo, and were often known as Shômiyô (“lesser names”), in contradistinction to the Daimiyô (“greater names”). The main difference, however, between the higher and lower nobles seems to have been less one of birth than of property—the Daimiyô being holders of lands of which the produce was valued at 10,000 kokus of rice annually, or more; the Shômiyô, of lands of which the annual produce was under 10,000 kokus.

Page 3. The Twelve Naishi.

A Sinico-Japanese word, meaning “inner attendants.” They were noble ladies, daughters of Kugé, who were peers of the Mikado’s creation, higher in rank than the Daimiyô (who were, in reality, nothing more than deputies of the Shôgun), but possessed only of small estates, and of little direct power or influence. Their duties were to wait upon the Mikado and his consort (K’wôgo).

Page 5. Yoshida Kenkô.

A mediocre versifier, who flourished under the Shôgunate of Takauji. Some of the pieces in the well-known Kokinshiu (“Songs, New and Old”) are attributed to him. He was also the author of a collection of essays on all sorts of subjects of very little intrinsic interest or value, known as the Tsure-dzure-smsa.

Page 8. Ôgon.

Ôgon should be translated “barred gold pieces.” The coins referred to were probably Ôban. Ôban, Koban, and silver coins seem (according to the Kingin-dzumoku) to have been first issued in the nengo Tenshô, (A.D. 1573–1596); though in the same work we find hints that coins were in use as far back as the nengo Tengiyô (A.D. 938–947). The “ôban” was a thin plate of gold (or heavily-gilt silver) of oval shape, about 6 inches long by 4 inches broad, marked with various stamps and seals, rough on the one face, generally on the other covered with an elaborate design, consisting of rows (commonly seven) of transverse shuttle-shaped depressions. The Tenshô ôban contained 44 momme of gold (a momme was, I believe, about 58 grains troy). On the ornamental face are written the characters “ten riyô,” by which are meant, says the Kingin Dzumoku, ôgon, or fine gold, riyô, so that each ôban was worth 420 momme of silver. The seal was a paraph of the characters “yei-jô,” which signify literally “glory and order.”

Page 20 (note). The Japanese “abacus” or calculating board.

The reader is referred to the article on Arithmetic in the “Encyclopædia Britannica,” where a full account of the abacus in use in China, (swanpan), and in Japan (soroban) will be found.

Page 26 (note †). The word “suma” is a misprint for “tsuma.”

Page 37. Kamishimo.

A sort of outer ceremonial dress, of stiffened material, curiously shaped about the shoulders so as to present a winged appearance. The trader-class, as well as the samurahi, seem to have had the right of wearing it on certain occasions. A peculiar Kamishimo, without any device or crest, was worn by a samurahi when committing seppuku.

Page 45. Example set by the falcon.

“Taka wa shishite mo ho wa tsumadzu.”— The falcon even at the point of death will not peck at an ear of rice. Of such a noble nature is the bird, that it would rather die than rob the peasant of a single grain of rice.

Page 47. I am as fortunate as if I were to come upon the Udonge in bloom.

In the great Sinico-Japanese Encyclopædia—Wa Kan Sansai-dzuye, “Japanese and Chinese Illustrations of the Three Powers (Heaven, Earth, and Man),”—vol. 94, part 1, under the heading of Basho, we are told that the Udonge is a kind of fig-tree. In vol. 88, under the word Ichijiku, the Udonge is again declared to be a kind of fig. The popular notion is that the Udonge blooms but once in three thousand years, a notion derived, doubtless, from the fact that, in figs, the flowers being within and not without the receptacles, are not externally visible; and hence the tree appears never to bloom.

In the Nehankiyo, a Buddhist doctrinal work said to have been composed shortly after the death—or perfection—of Sakya Muni, the manifestation of Buddha upon earth is announced as a most rare event—rare as the blooming of the Udonge.

In the century of poems collected by Kiu-an, there is a stanza referring to the Udonge, of which the following is a literal rendering:—

“The reign of our Emperor,

May it be as the Tama-tsubaki,

Everlastingly green;

May his days be so long in the land

That he may behold the Udonge bloom a hundred times.”

The Tama-tsubaki is a hardy ever-green shrub, apparently identical with the Euonymus Japonicus. The Ficus Indica, it will be remembered, is reverenced by the Southern Buddhists as a sacred tree.

Page 52. “Namu Amida Butsu,” or “Namu miyôhô renge kiyô.”

Introductory phrases of Buddhist prayers. The words are neither Japanese nor Chinese, but are altered Sanskrit. The first is said to mean “O aid me, thou everlasting Buddha,” or “Buddha of boundless light.” Amida, Amita, or Amitabha, is a personage of the later Buddhism, especially honoured in China as the king of the paradise in the Western Heavens. “Namu” is the Sanskrit “namoh,” Pali “namo” used in invocations. The second, translating the Chinese characters in which it is commonly written, would seem to signify: “O precious law and gospel of the lotus-flower.” It is commonly used, if I remember rightly, by members of the Nichiren sect. Good souls are supposed to live for ever, perched upon a lotus-flower. Sadakuro tells his victim to choose whatever prayer he may prefer, and die without further delay.

Page 54. In the text, the teeth of Karu are said to have been unblackened, which evidence of her youth has been erroneously omitted from the present version.

The extraordinary custom of blackening the teeth and shaving off the eyebrows was originally practised by legally-married women only, but gradually came to be adopted by all women who had attained their twenty-second or twenty-third year, whether married or not. The practice of shaving off the eyebrows is said to be falling into desuetude, and the teeth are now, it is believed, blackened by married women alone, and even by them only after having given birth to a child. The material used in blackening the teeth is a preparation of gall-nuts and oxide of iron. The custom is said to have arisen in the reign of the Emperor Daigo (10th century), but I have not been able to find any satisfactory explanation of its origin or meaning.

Page 55. The Bon month.

That is, the 7th month, when, on the 13th, 14th, and 15th days, the Bon festival, or feast of lanterns, is held. The Chinese characters representing the word Bon mean “demon or spirit-period,” but the etymology of the word is unknown to me. The popular term is Tama-matsuri, for Tamashii no matsuri, “feast of ghosts”—All Souls’ Day, as we should say.

A shelf is erected in the principal chamber of each house, on which rushes are laid, and over which the ihai,[7] or tablets of the departed, are suspended, in the hope that their spirits will revisit the scene of their earthly life. A cord is carried across the shelf (Tamadana, or spirit-shelf), from which depend various fruits, such as millet (Panicum italicum), Hiye (Panicum cruscorvi), water-bean nuts (Nelumbo nucifera of Gœrtner), chestnuts, and egg-apples or brinjals (often called aubergines, fruit of Solatium melongena). Various boiled cereals are also placed upon the spirit-shelf, laid on leaves of the water-bean.

On the 13th day, about sunset, an ogara, or hemp-stalk dried after having been peeled, is lit. The flame, which lasts only a short time, is the Mukai-bi, or “greeting-flame,” welcoming the spirits on their arrival. On the evening of the 15th, the ceremony is repeated, and the Okuri-bi, or “speeding-flame,” signifies the farewell of the living to the departing ghosts of the relations or ancestors whose thai are suspended over the spirit-shelf.

Page 56. Inari.

Name of a Shintô deity, the patron of rice-farmers. The Chinese characters of the name mean “the bringer of rice.” The name Inari itself is Japanese, and is probably connected with the word ine—growing-rice, paddy. The fox (Kitsune) is supposed to be attached to the service of the god.[8]

Page 56. Nyogo Island.

Said to he inhabited entirely by women. An account of it is given in the Yumi-hari-dsuki, a sort of romance founded upon the adventures of Yoritomo on a supposed visit to the island, which is placed in the neighbourhood of the Loo-choo group.[9] The egg-plant (Solanum melongena), or brinjal, is described as growing there to such a prodigious size that ladders are necessary to get at the fruit.

Page 67. We shall climb together the Shidé Hill.

In the the mythical geography of Buddhism, a hill over which souls have to pass on their journey to hell or paradise. Some distance beyond it, they arrive at a place where three roads (San-dzu) meet, one of which leads to hell (jigoku), another to paradise (gokuraku), and the third from the world. Before continuing their journey—to hell or to paradise, as may have been decreed—the ghosts strip off their clothes, and give them up to an old woman whom they find stationed there to receive them, under a pine-tree. The old woman is known popularly as San-dzu no obâsan.

Page 68. That you may take it with you on the dark path.

The dark path is an euphemism for death. Ghosts are supposed to go under the world, where both hell and paradise seem to be situate; hence the expression, “to go on the dark path.”

Page 76. Jinseng medicine.

Jinseng or Ginseng is the aromatic root of a species of Panax, a member of the Ivy family, much esteemed in China, and to some but a less extent in Japan, as a tonic and a stimulant. The plant is said to live for a thousand years, and then to assume a human form. The infusion, if given to a moribund, is supposed to prevent decomposition.

Page 77. A high Kagura feast.

There are two kinds of Kagura festival, both connected with Shintôism, commonly celebrated in Japan. That referred to in the text is known as a Dai-dai Kagura—lit., “great great Kagura”—and is essentially a solemn adoration of the Sun-goddess (Amaterasu no Ohongami, or Tenshokô Daijin), followed by a sort of banquet, of which the expenses are defrayed by subscription. The solemnities, which are conducted by Kannushi (Shintô priests, guardians of shrines), take place in the hall of a Shintô miya, or temple, previously guarded from evil influences and from intruders by a roughly-made rice-straw rope carried round its walls. First, the O-harai (august purification) of the Sun-goddess is placed upon a stand, and proper offerings are set before it. The O-harai is a kind of box containing a fragment of the staff wielded by the priests of the temple of the goddess in Isé, at the festival there held in her honour twice every year. Each Kannushi then takes a branch of Sakaki (Cleyera Japonica), which he holds in one hand, while with the other he commences to beat upon a small drum. The attention of the goddess being thus aroused, the assembled clergy, who have previously disposed themselves in a semicircle in front of the stand upon which the O-harai was placed, chant, in a monotonous drawl and to the accompaniment of the drums which they do not cease to beat, a special liturgy (norito) to the Queen of the Plains of High Heaven (Takamagahara). The liturgy ended, O-harai inscribed with the name of the Sun-goddess are bestowed upon the laity,[10] who, ranged in front of the shrine, have assisted at the ceremony, and the proceedings, passing, pleasantly enough, “from grave to gay,” terminate with an entertainment, in which those who have subscribed to the expenses, no doubt, duly play their part. One of these O-harai ought to find a place upon every domestic Kami-dana or god-shelf—a small model of a Shintô temple to be found in almost every house, labelled with the names of various deities, one of whom must be the Sun-goddess—for it affords protection to the believer’s household—only, however, for a period of six months, when it must be changed for a new one brought or fetched from Isé.

For the above description I am in part indebted to Mr. Satow’s account of the Shinto temples in Isé, contained in the 1873–4 volume of the Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, where a vast amount of information on the subject of Shintôism will be found. The following specimen of a Shintô prayer, which I quote from Mr. Satow’s admirable essay on the “Revival of Pure Shintôism,” printed as an appendix to the first part of the third volume of the Transactions already cited, will, it is believed, be read with interest.

“From a distance I reverently worship with awe before Ame no Mi-hashira and Kuni no Mi-hashira, also called Shinatsu-hiko no Kami and Shinatsu-hime no Kami, to whom is consecrated the Palace built with stout pillars at Tatsuta no Tachina in the department of Heguri in the province of Yamato.

“I say, with awe, deign to bless me by correcting the unwitting faults which, seen and heard by you, I have committed, by blowing off and clearing away the calamities which evil gods might inflict, by causing me to live long like the hard and lasting rock, and by repeating to the gods of heavenly origin and to the gods of earthly origin the petitions which I present every day, along with your breath, that they may hear with the sharp-earedness of the forth-galloping colt.”

The other kind of Kagura is a kind of mystery or musical pantomime, enacted at the shrine of a local deity, in a sort of raised building or theatre accessory to the shrine and called Kagura-dô. The celebration may be in honour of the local deity, and then takes place upon his death-day, or may simply be intended to propitiate heaven generally. The expenses are usually defrayed out of the offerings of pilgrims, and by contributions from the Ujiko—the dwellers under the protection of the god to whom the shrine is dedicated. Before the mystery opens, a particular kind of sudzu, Kagura-sudzu, and two gohei are placed in front of the Kagura-dô. The Kagura-sudzu consists of twelve small bells, resembling those fastened round the tails of pack-horses in Japan, or those attached round the necks of mules in European countries, curiously strung together. A gohei, the proper Japanese term for which is mitegura, is a kind of wand, from one end of which depend, on either side, strips of paper, notched or slit in a particular manner, so as to present a twisted appearance. Woodcuts and descriptions both of the Kagura-sudzu and gohei will be found in the 15th volume of the Wo Kan Sansai-dzuye. The object of the bells is to call the attention of the god to what is about to take place; and the gohei represent—according to Mr. Satow—offerings of rough and fine cloth, which are supposed to attract the god to the shrine. The mystery is then inaugurated by a Miko, a sort of virgin priestess, generally a daughter of the Kannushi, presenting herself, carrying sometimes the sudzu and gohei, sometimes a sword, and going through a series of conventional gestures, which have the effect of purifying the spot from all uncleanliness, and of keeping all evil demons at a proper distance.

These preliminaries over, and the place thus made fit for the reception of the god, the dance commences, regulated by the music of a small band, consisting of drums and fifes. The dancers accompany their movements by significant gestures by which the plot or tale is told, no singing or shouting being permitted. The number of performers varies considerably: all are clad in antique costumes, with tall caps on their heads, long sleeves and preposterously lengthened hakama, or trousers, which turn up under their feet and are trailed behind, and all wear masks—one simulating the head of a fox, another the fierce look of a robber, a third the countenance of a mild genius, a fourth that of a demon, while others have the expression of a clown or natural, or are provided with horns, or show a protuberant snout like that of a pig, or have the cheeks prodigiously swollen and the forehead absurdly dimished.

The pantomime is various, but the following always forms a part of it. A dancer wearing the mask of a gentle genius is attended by another wearing that of a clown and carrying in his hand a bow and arrows. The former represents Hikohoho no Mikoto, one of the demi-god rulers of Japan. Their dance is grave and solemn, but is soon interrupted by the advent of a sturdy performer, who comes to the front strutting and stamping with great energy. This is Honosusori, a demon, wearing an appropriate mask and provided with a fish-hook and line. On approaching Hikohoho, he drops his swagger and humbly salutes the superior genius, intimating by gestures that he can make no use of the fish-hook and line, and begging to be allowed to barter it for the bow and arrows carried by the god’s attendant. His request being granted he retires in triumph; and Hikohoho tries his luck with the hook and line, but the first fish he catches breaks the line and makes off with the hook. The angler and his attendant thus discomfited, pray to the dragon-deities of the sea, who recover the hook and line, and present them to Hikohoho, who immediately returns both to Honosusori and takes back his bow and arrows.

The dance ended, the Miko dips a bamboo branch (Arundo bambos, Thbg) in warm water—according to some, the water of a bath which she has previously taken—and flirts a shower of drops over the assembled Ujiko. As the deity is supposed to have become incorporated with her body for the nonce, each drop so flung has a miraculous power, and those who are fortunate enough to be within their range may expect to be cured of all their ills.

The pantomime of Hikohoho and Honosusori is intended to commemorate the invention of angling; and the mystery, as a whole, is, according to Japanese tradition, a representation or imitation of the efforts made by the gods of old to induce the Sun-goddess to sally forth from the cavern to which she had betaken herself in a lit of dudgeon.[11] And, indeed, it seems probable enough that it is a relic of the sun-worship which appears to have been the earliest definite form of religion in the country, and simply signifies the joyous welcome with which the rising of the sun over the illimitable waters of the Eastern Sea was hailed by the primæval fishermen who dwelt on the shores of Dai Nippon. The etymology of the word is uncertain. Some derive it from kami, a god, and eragi, to laugh, and this derivation is countenanced by the fact that the Chinese characters by which the word is ordinarily represented mean “the pleasing of the god.” To my mind, however, the more probable derivation is that from kami and kura, a seat.

The legend of the withdrawal of the Sun-goddess is a good example of the Japanese myth; and the following account of it, taken, in great part, from Mr. Satow’s description of his visit to the Shinto temples in Isé, cited above, will not be without interest to the curious reader.

After the consummation of the marriage of Izanagi and Izanami, the first male and female deities and the immediate creators of Japan, the god Izanagi underwent a long purification by washing in the sea, in the course of which the Sun-goddess Ama-terasu no ohongami, “the mighty goddess brilliant in heaven,” was developed from his left eye, while from the right orb was produced Sosa-no-o no mikoto, or the Moon-god. Of all the numerous progeny of Izanagi these two were the most dear to him. He therefore resolved to make the Sun-goddess the ruler in heaven, and she accordingly climbed up the pillar on which heaven then rested, to assume the place assigned her. The Moon-god, on the other hand, was given the sovereignty over the blue sea; but the god neglected his kingdom, and the earth became desolate in consequence. On being asked the cause of his evil temper, the Moon-god replied that he wished to go to his mother Izanami, who was under the earth, and his father thereupon made him the ruler of the night. This, however, does not seem to have satisfied the god, for he committed various offences—among others, that of flaying alive a piebald horse from the head to the tail, and then throwing the carcase at his sister, who was seated at her loom, so alarming the goddess that she injured herself with the shuttle, and, full of fear and wrath, retired into a cave, the mouth of which she closed with a door of solid rock. Heavens and the earth were thus plunged into utter darkness, of which the more turbulent of the gods took advantage, filling space with a buzzing noise, and the general disaster was great. The gods then assembled in the dry bed of the Amenoyasu River—the River of the Peace of Heaven—and consulted as to the best means of appeasing the goddess. After much deliberation, the following device was hit upon. Iron was obtained from the Celestial mines, and the god Ishikori-dome, with the assistance of the divine blacksmith, Amatsumore, after twice failing, succeeded in forging a large and perfect mirror. “This, according to the legend, is the august deity in Isé.”

Other gods meanwhile planted “Kodzu” (Broussometia) and “Asa” (Hemp), and from the bark of the former and the fibre of the latter coarse and fine clothing was prepared for the use of the goddess. A palace was also built for her, ornaments made to adorn her person, and a sacred wand fashioned out of the wood of the “Sakaki” (Cleyera Japonica) to place in her hand.

Tearing the bones out of the foreleg of a buck, the gods then set this in a fire of cherry-wood; the bone cracked in a particular manner, which was considered to afford a favourable omen, and preparations were at once commenced to entice the goddess from her seclusion.

One god pulled up a Sakaki tree by the roots, hanging on its upper branches the mirror, and on the lower the coarse and fine clothing. Another god then took the tree so adorned, and held it in his hand while he praised in a loud voice the power and beauty of the goddess.

A number of cocks were next collected and made to crow in concert. The god Tajikara (strong’i’th’arms) was posted close to the door of the cavern. The goddess Ame no Udzume was chosen as a sort of mistress of the ceremonies, and having adorned her head with a kind of moss, and bound up her sleeves with the stem of a climbing plant, commenced to play upon a sort of rude bamboo flageolet, accompanied by another god, who drew music from the strings of six bows, arranged with the strings uppermost (the origin of the “Koto,” a kind of horizontal harp), by drawing across them the rough stems of a tall kind of grass and of a rush, while the rest of the gods kept time with wooden clappers.

Bonfires were then lit in front of the cavern, and a circular box, “uke,” placed near, on which Udzume mounted and began to dance, singing a song of which the words have been preserved:—

“Hito futa miyo

Itsu muyu nono

Ya kokono tari

Momo chi yorodzu.”

These words are said to have been chosen afterwards to express the numerals

One two three four

Five six seven

Eight nine ten

Hundred thousand myriad.

There is a difficulty, however, in identifying “tari” with “to,” ten. But the stanza is susceptible of a totally different interpretation, and may be taken to mean

Gods! behold the door,

Lo! the majesty of the goddess;

Shall we not be filled with delight?

Arc not my charms excellent?

The last line is an invitation by the singer to the assembled deities to gaze upon her beauty.

These proceedings excited the mirth of the gods, whose Homeric laughter caused the heavens to tremble. The rest of the legend may be told in Mr. Satow’s own words.

“Amaterasu Ohonkami thought this all very strange, and having listened to the liberal praises bestowed on herself, said ‘men have frequently besought me of late, but never has anything so beautiful been said before.’ Slightly opening the cabin door, she said from the inside ‘I fancied that in consequence of my retirement both Ama no Hara (heaven) and Ashiwara no Nakatsukuni (Japan)[12] were dark. Why has Ame no Udzume danced, and why do all the gods laugh?’ Thereupon Ame no Udzume replied: ‘I dance and they laugh because there is an honourable deity here who surpasses your glory’ (alluding to the mirror). As she said this, Ame-no-futadama no Mikoto pushed forward the mirror and showed it to her, and the astonishment of Amaterasu O-mi-kami was greater even than before. She was coming out of the door to look, when Ame-no-tajikara-o no Kami, who stood there concealed, pulled the rock door open, and, taking her august hand, dragged her forth. Then Ame-no-kogane no Mikoto took a rice-straw rope and passed it behind her, saying: ‘Do not go back in behind this.’ ”

Udzume is commonly called Okame, and is represented in the Kagura by the dancer whose mask is a human face with puffed-out cheeks and diminutive forehead.

Page 83 (note). Names of Women.

Women do not use surnames, not even those of their husbands, and are known by one name only. In addressing them the honorific “O” is prefixed, and the honorific “sama” (often contracted into “san”) added. Thus, “Yuki,” snow, becomes O Yuki san,—Miss Snow; “Tsuru,” crane, O Tsuru san,—Miss Crane; “Kane,” gold or metal, O Kane san; “Hana,” flower, O Hana san; “Sono,” garden, O Sono san, &c, &c.

Page 98. The sage Sonko and the philosopher Riuto.

Both appear to have flourished under the Tsin dynasty (A.D. 265–317). On looking into their biographies, I find nothing worthy of record beyond the anecdotes in the text.

Page 100. Gi-on Street, the Temple of Kiyomidzu, the great Buddha at Nara, the Hall of Chion, and the Temple of Kinkaku.

The Gi-on Street was, and still is, the principal pleasure-street of Kiyôto.

The temple of Kiyomidzu (“the temple of the Limpid Waters”) is sacred to Kwanon—Chinese, Kwanyin—the Buddhic Venus of the Far East. It is much visited by women, especially by those who desire children. In the grounds is a famous waterfall called Otowa no Taki, the waters of which are supposed to be endued by the goddess with various healing and invigorating virtues.

Nara is eastwards of the line joining Kiyôto and Ohozaka. Formerly the Tenshi (Emperor) resided there, but it does not seem ever to have been the real capital as some pretend. Mr. Brunton, C.E., in a most interesting article upon native constructive art, printed in the Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan (1873–4, p. 81), gives an account of the Buddha, from which the greater portion of the following brief description is taken.

The image is contained in a temple 292 feet long, 170 feet broad, and 156 feet high—that is, to the arête of the roof, which is supported by 176 pillars. The height of the Buddha, which is in the usual squatting position, is 53½ feet, the length of the face being 16 feet, the width of the shoulders 28 feet 7 inches, and the length of the middle finger 5 feet 6 inches. On the head are 966 conventional curls. The glory or halo is 78 feet in diameter, and on it stand 16 figures, each 8 feet high.

Two images are placed in front, each 25 feet high.

The whole is in bronze, cast in pieces, afterwards soldered together, and the “whole construction shows great skill and original genius in the mixture of the metals, and in the methods of casting them.”

The total weight of metal is about 450 tons, consisting of the following ingredients:—

| Gold |

|

500 | lbs. | Avoirdupois. | ||

| Tin |

|

16,827 | lbs.„ | Avoirdupois.„ | ||

| Mercury |

|

1,954 | lbs.„ | Avoirdupois.„ | ||

| Copper |

|

986,080 | lbs.„ | Avoirdupois.„ |

This is the largest Buddha in Japan, and was first erected in 743 A.D., but was twice destroyed in the course of the wars that desolated Japan about that time, and the present image was set up in the 12th century. Six times in succession the casting failed, and it was only at the seventh essay that a successful result was obtained. The head is said to be much more modern than the rest of the figure.

The Hall of Chion (Chi-on In).—A celebrated temple in Kiyôto of the Zenshu (Buddhist) sect. The name In is generally given to a Buddhist temple of a higher, Tera to one of a lower, order. An intermediate kind exists, on which the appellation Ryô is bestowed. Chi-on In may be rendered as “The Hall of Intelligent Benevolence.”

The Temple of Kinkaku.—Erected by Taiko-sama, more renowned for its decoration, internal and external, than for the beauty of its situation. In fact, the temples of Kiyôto have been overpraised. None are comparable to the Shiba temple, lately destroyed by fire, in Vedo, or to the great Tôshô-gu at Nikko. Kinkaku may be translated “Golden Palace.”

Page 111. The devotion of Goshisho.

Goshisho was a minister of a king of Go (Wu), who, despite his remonstrances, neglected the affairs of the state and engaged in a long and disastrous war with the state of Yets (Yueh). Upon Goshisho strongly advising his master to have nothing to do with a beautiful girl sent to him as a present by the king of Yets, the king of Go became so enraged that he ordered his faithful minister to be decapitated and his head exposed. Shortly afterwards, he was taken prisoner by his adversary and led in chains past the very spot where the head of the unfortunate adviser was exhibited, the features of which were observed to form themselves into a bitter smile as the degraded king went by.

Page 112. Hero Yojô.

Yojô (Yü Jang) was the minister of a king of Shin (Tsin), who was defeated and slain in a war with a king of Shin (Ts’in). Yojô vowed revenge, and in order effectually to disguise himself swallowed varnish (some say, lime), which caused an eruption to break out in his face that completely changed his appearance. One day, hearing that the king of Ts’in would ride over a certain bridge, he stationed himself under it, armed with a sword, and awaited his enemy’s approach. As the king of Ts’in came near, his horse refused to cross the bridge, despite the efforts of his rider, who, thinking there must be some cause for such an extraordinary aversion, ordered his attendants to search the neighbourhood. They did so, and found Yojô, whom they brought to their master, to whom he confessed his designs. The king laughed at the presumption of Yojô, and, handing him his mantle, said scornfully, “Stick your sword through that, and imagine that my body is within it. Thus you can satisfy your longings for vengeance.” Yojô took the mantle without saying a word, and, wrapping it round himself, thrust his sword through it into his body and fell back dead.

Page 112. The secret books of Son and Go.

Son (in Chinese, Sun Wu or Sun Tsz) was a celebrated Chinese commander of the 6th century before Christ, in the service of Ho Lü, prince of Wu. He was also the author of a book on military science still in use. The “Three Steps and Six Methods” is the book bestowed upon Chôryô by the genius Sekiko. (Vide post, “Chôryô.”)

Go (Chinese, Wu K’i), a famous general in the service of Ts’u (a feudal state under the Chen dynasty, flourishing from the middle of the 8th to the latter third of the 4th century before Christ). Ordered to march against the state of Ts’i, of which his wife was a native, he put her to death lest she should persuade him to deviate from his duty. He was finally taken prisoner and slain by the people of Ts’i. He wrote a book on strategy, which is still esteemed by military men. (See Arts. 635 and 866 of Mr. Mayers’ “Chinese Readers’ Manual.”)

Asano Takumi no Kami was the real name of the prototype of Yenya. Takumi no Kami was the designation of his office, overseer of works; but Asano Takumi, in the common language, means “poor in resources,” “shallow in conception,” “witless,” and the like.

Page 115. The thread of his existence was snapped in twain.

The soul is supposed to be a material substance of irregular bag-like form, kept within the interior of the body by a sinuous prolongation or “thread” attached to some part of the human frame. On this “thread” being snapped, the soul flies forth and life is terminated. The expression in the text tama no o may also refer to the rosary used by Buddhist priests, which consists of a hundred and eight beads strung together in the usual way. These hundred and eight beads are said to represent the hundred and eight lusts, cares, miseries, and vanities of the world; and as the sundering of the thread puts an end to the existence of the rosary, so the destruction of that human consciousness which links together the troubles of the world puts an end to all human ills and sorrows.[13]

Page 115. Komusô.

A class of men who, either from remorse or from disgust with the world, abandoned society to lead the life of wandering mendicants. They were—for the practice has now fallen into desuetude—generally samurahi, and went about dressed in white, wearing a curious deep-brimmed hat[14] which entirely concealed their features, and playing a sort of rude flageolet as they solicited alms. No special religious meaning seems to have attached to the custom. But the etymology of the word points to that contemplative life which leads to absorption in nirvana, and the practice therefore was, in all probability, more or less under the sanction of Buddhism.

Page 119. Warahi books.

Lit. “jest-books,” but in reality obscene novels and woodcuts, which, even under the old regime, the higher classes in Japan at least avoided diverting themselves with in the presence of others, and did not boast of possessing.

Page 122. Village and household gods.

The household god (ujigami) is, strictly speaking, the common ancestor of the clan, and corresponds with the Lar Familiaris of the Romans, or the Herôs epônumos of the Greeks.

The village gods (ubusuna no kami) are the local gods, but just as the Penates of the Romans often included, or were synonymous with, the Lares, so the ubusuna no kami seem to be confounded with the ujigami. Thus the inhabitants of a district under the protection of a special deity arc commonly called the ujiko, or members of the family of the deity, who himself is known generally as the ujigami. On this subject much information will be found in Mr. Satow’s essay on the “Revival of Pure Shintôism” previously referred to.

Page 122. High civil and military rank.

Lit., to the command of his troops and the governorship of his province.

Page 130. His manhood roused by his wife’s cry of distress.

Allusion is here intended, I believe, to the otokodate of Bandzui Chôbei, a sort of Japanese knight errant, or, more properly, benevolent brigand who robbed the rich to aid the poor, and enforced a code of his own against the oppressor in favour of the oppressed.

Page 135. The Hero Chôryô.

In Chinese, Chang Liang. One of the principal partisans of the founder of the Han dynasty. He died in the early part of the 2nd century before Christ. (See Art. 26 of Mr. Mayers’ work cited above, and the note to page 135 supra.

Page 142. Ihai.

These tablets are inscribed with the posthumous name (okuri-na) of the deceased and the date of his death. When the wife survives the husband, she often has her name added in red letters, which upon her death are converted into black ones. Ihai are placed upon the Buts-dana, or Buddhist shelf, and also—as stated in a previous note—on the Tama-dana, or spirit-shelf, on All Souls’ Day. The ancestral halls common in China, in which the tablets of the ancestors of a family, or sometimes of a clan, for several generations back, are honoured, are not found in Japan.

The Eighth Book consists of a metrical description, mainly in the form of a dialogue, of the journey of Tonasé, the wife of Honzô, the Karô of Wakasanosuke, with her daughter, Konami, from Kamakura to Yamashina, a small village hard by Kiyôto, where they hope to find Rikiya, the son of Yuranosuke the hero of the story, who, since the destruction of the house of Yenya, had withdrawn with his father into an obscurity hitherto impenetrable. It will be remembered that in the Fourth Book Rikiya is affianced to the daughter of Honzô.

On the stage, this portion of the romance would be sung or recited with appropriate gestures, so arranged as to form a kind of continuous slow dance, to the accompaniment of music.

The following attempt at a versified rendering[15] claims the indulgence of the reader. The translator has endeavoured to preserve, as far as possible, the spirit and even the letter of the original, although at the risk of roughness being perceptible in the execution of his task; but as the point of the text often lies in an untranslatable play upon words, he has been obliged in one or two instances to omit, and in others to modify or amplify, portions of the interlude.

- ↑ The etymology of this word is uncertain. It is, however, a Sinico-Japanese compound, and the Chinese characters by which it is represented mean “the pure blue porcelain glaze,” or, metaphorically, the genius of tragedy. According to a writer in the Japan Mail of March 10th, 1875, this species of composition takes its name from Jôruri Himé, the mistress of the favourite Japanese hero Yoshitsune, the brother of Yoritomo, the founder of the hereditary Shôgunate (A.D. 1180, circiter); and, though afterwards chiefly used in tragic narration, was first employed in telling the tale of the loves of the frail princess. More probably, however, the latter fact has, by a kind of metonomy, invested this Japanese Timandra (Yoshitsune may, without impropriety, be called the Alkibiades of Japan) with a posthumous title which it were not, perhaps, too fanciful to render as “The Muse of the Drama.”

A jôruri, at the present day, is a sort of dramatic part-prose part-metrical romance, commonly of a tragic cast, of which the dialogue may be recited or sung by actors, with appropriate gestures: the utaigata, or song-men of the orchestra, interposing, from time to time, with the narrative, which is often cast in a sort of irregular verse, and thus discharging to some extent the functions of a Greek chorus.

- ↑ The original text of the translation now offered differs somewhat—in places, considerably—from that resorted to for the earlier version.

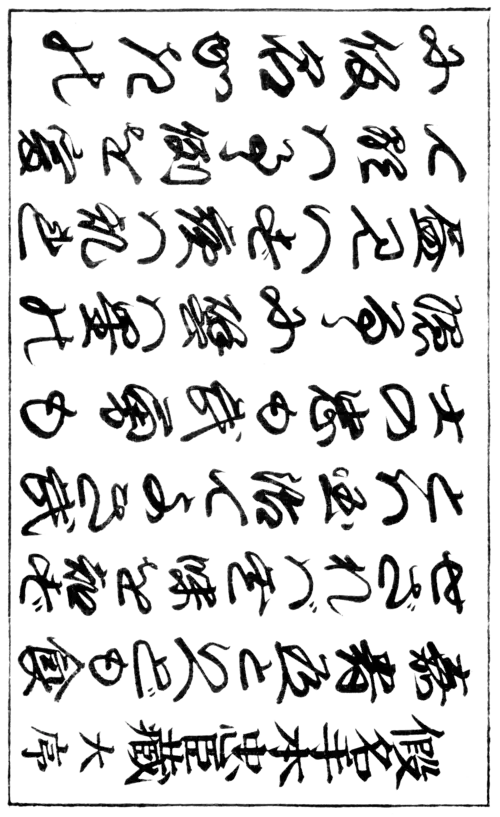

- ↑ I.e. “grass writing,” a cursive abbreviated mode of writing, more commonly used in Japan than the ordinary square Chinese. The principal difficulty in the acquirement of the written language lies in the decipherment of this variable and puzzling form, well termed by the old Spanish missionaries an invention de un conciliabulo do los demonios para enojar a los fideles, and several years’ assiduous study are necessary to obtain a useful command of it, which can be retained afterwards only by constant practice. The advantages that would result to the Japanese from an adoption of the Roman characters—a perfectly feasible change—are simple incalculable. A real foundation would thus soon be laid, on which a true national civilization, very different from the mere imitative and often very laughable travesty of Western forms, beyond which the Japanese, for the present, seem unable to advance, might be based; and the land of Dai Nippon, which can at least boast of never having been insulted by the tread of the conqueror within historic times, would rapidly assume a leading position among the ancient empires of the Extreme East.

- ↑ Asano died in the month of March, when the wild-cherry, so often the theme of Japanese poets and artists, is in blossom—a fugitive beauty soon perishing under the rough blasts of the equinoctial gales.

- ↑ The town of Odawara, so well known to European residents, was the principal seat of this family, who had a strong castle there, now in ruins and held sway over a large extent of the surrounding country.

- ↑ Vide Mr. Satow’s Geography of Japan, Trans. As. Soc. Jap., 1872–73, p. 33.

- ↑ Vide post.

- ↑ A different explanation is somewhere given by Mr. Satow, but the translator is, unfortunately, unable to say where it is to be met with.

- ↑ The Japanese commonly identify this mysterious island with Hachijo, Dotes of a visit to which island will be found in Vol. vi. part iii., of the Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan.

- ↑ Strictly upon the Ujiko only—that is, upon the dwellers in the district over which the local deity, worshipped at the shrine where the Kagura is celebrated, is supposed to extend his protection.

- ↑ It is no objection to this theory that the shrine at which the Kagura is enacted may not be dedicated specially to the Sun-goddess, for the latter, as the Queen of Heaven, is supposed to have a general right of tenancy of any shrine, and all local duties are more or less under her control.

- ↑ The middle country of reedy moors.

- ↑ “Tama no o” is also an extravagant grammatical term equivalent to “syntax.” The idea being that the latter, as a sort of connecting link between words, may be fitly designated by such an expression as the “thread of jewels.” See Mr. Aston’s Grammar of the Written Language.

- ↑ See the woodcut opposite page 105.

- ↑ A previous translation by the present writer will be found in an Essay on Ancient Japanese Poetry, contained in the Westminster Review for October 1870.

Konami.

“Its name upon this fleeting world[1]

Who first bestowed, O rapid Aska,[2] say,

Whose restless waters aye have swirl’d

Thro’ changing channels; as changeful is the way

Of Life to us from happiness hurl’d—

A Wavelet[3] breaks upon thy famous strand

Whom Yenya welcomed as the bride

Of his esquire who long had sought her hand,

Low fall’n with Yenya’s fall her pride;

She was betrothed and Kakogawa’s child

Fond hope deep in her being bore,

But Fortune adverse ne’er upon her smil’d,

No bridal gifts exchang’d,[4] no more

By lover sought, her soul is sad.”

Tonasé.

“Peace, daughter, peace; thy mother bids thee haste

Towards Yamashina, where glad

Thou shalt by bridegroom surely be embraced.

Alas! a bride-train thus forlorn

Hath never yet in all the world been known,

With doubt and grief my heart is torn;

Without attendant, mother and child alone,

On foot must urge their weary way,

And strive Yamato’s far-off land to gain.”

Konami.

“My body’s white as snow, men say,

The chilly winds with crimson hues it stain

Such as the wild-plum’s flow’r make gay,

My fingers all are sore benumbed with cold,

Apt name Kogoye[5] pass is thine;

O’er Satta’s ridge our toilsome way we hold,

Thence gazing back the curling line

All pensive watch of vaguely erring smoke

That issueth from Fuji’s peak

And van’shing in the lofty sky is broke;[6]

How sweet if ’twere the bonfire’s reek

At threshold lit[7] my welcome home a Bride,

How ’twould our sadness charm away!

With pines o’ergrown Matsubara’s[8] plain so wide

Now travers’d, crowded is the way,

The sea-coast way,[9] by some high Daimiyô’s train,

I know not whose; how blithe and gay

They seem: ah! when shall I know joy again?”

The Bridal Journey.

Tonasé.

“O would that Fortune smiling were

Upon us, proud thy bridal train should be;

Than thee none happier, none more fair.

Now yonder may we Sur’ga’s Fuchiu[10] see.

The omen cheers thy mother’s heart,

Her child shall yet the marriage pledge exchange,

By husband yet be led apart

In bridal bower, sweet vows to interchange.

In tender whispers heard by none.

Narrows the path thro’ th’ briars hardly seen,

To parents as to child[11] unknown;

Fain would’st thou now on lover’s strong arm lean.”

Konami.

“On Mariko’s sunny bank we stand,

His rapid stream shall roll our griefs away,

Dear mother; now on our right hand

High Utsu’s hill we leave behind, O say

Shall I a bridal pillow press,

Half-sleeping, by a husband’s arms embraced?

What mighty cares my mind distress,

Ohoi[12] river! thou whose waters haste

In rapid tumult onwards sped,

As fleeting often is the love of man,

Yet ’tis not fickleness I dread

In him I love, but ’neath misfortune’s ban

Our love’s full flow’r can hardly blow.

Our feet upon Shiradsuka’s bridge now stand,

Past Yoshida we further go

To Akasaka; our wearied limbs demand

Repose; the beckoning women[13] cry

That throng the door of every inn,[14] ‘Fair Bride,

To Kyomids’[15] far-famed temple hie,

To Otowa’s[16] plashing fall pray choose a guide,

And there, fair Bride, some space delay,

Adore the temple’s deity and view

How to Kwanon[17] the pilgrims pay

With sacred dance and music homage due,

Then join in the applauding shout

And share the merry throng’s loud happiness.’

‘Not so, my tale of tender doubt

To my chosen lord alone I shall confess.’ ”

Tonasé.

“Right, daughter; were thy lover here

Three suppliants we would Isé’s[18] gods revere.”

Konami.

“Thus we our clownish verses sing.

To Nar’migata’s[19] town we come. Success

The happy name, I trust, may bring.

Ha! Atsta’s shrine descry we yonder—yes,

Full seven leagues across the bay;

Haul taut the sail, bend, fellows, bend to th’ oar

With measured stroke—away, away—

Haste, haste, for distant still looms yonder shore.

Hark! how loud the rudder’s creak!

Meseems the chirp of some small sudsu[20] fly,

Or the grasshopper’s unceasing shriek,

The grasshopper that, as the old song tells,[21] doth cry

Thro’ the chilly nights when the hoar-frosts lie.”

Tonasé and Konami.

“How fierce the hail drives thro’ the windy air!

Our heads before its pelt we bend,

We lead, we follow the crossing boats that dare

Still with the howling storm contend.

Next Kamé’s hill we pass, awhile

At Seki halt, where from the eastern way

Parts stretching south for many a mile

The road to distant Isé,—the merry play

Of packhorse bells we hear as thee

We view, Sudzuka,[22] Tsuchi’s lofty peak,[23]

Rain-hidden, hardly may we see;

Rain ever hides, men say, the summit bleak,

O Minaguchi![24]—the rocky vale

Of Ishibé[25] we next fatigued toil thro’,

Pass Ohodsu, Mii’s[26] temple hail,

The hillside skirt, our further way pursue,

And now a petty hamlet nigh

Yamashina,[27] our journey’s end descry.”

- ↑ More literally, “floating”; hence variable, light, changing, unstable world. The earth is supposed to be suspended in the ambient atmosphere, as a fish in water. The following account of the creation, according to the ancient philosophy of Japan, extracted from the above-mentioned essay in the Westminster Review, may be interesting. “Originally all was chaos, matter existed but rude and formless. Divine influence penetrated the cosmic mass; a process of differentiation ensued, and the whole assumed an ellipsoidal form. Next the grosser parts became concentrated towards the centre, and the foundations of the earth were laid; while the more subtle parts receded and enveloped the globe with an ethereal fluid, of which the more delicate exterior layers constituted the sky, and those nearer to the earth’s surface formed the firmament. The notion of the existence of space apart from matter seems utterly strange to the philosophy of China and Japan, which, besides, never attributes the creation of the materials of chaos to any Divine First Cause; but owns, though impliedly rather than expressly, the self-existence of primeval unorganised matter and of some divine influence, not seldom, indeed, supposed to originate within and from the elements of chaos itself, by which the original substance of the Universe is forced to differentiate itself into elementary earth, air, and sky. From such a divine influence spring a multitude of powers personified as innumerable genii, who are the immediate creators out of the already partially developed materials of chaos of the animate and inanimate objects of nature, and to whom are entrusted the government and regulation of the phenomena and laws of the Universe.” The original text is full of word-plays utterly unsusceptible of translation, and the present version is, accordingly, in great part an imitation rather than an exact rendering of the Japanese. It is, however, believed that the meaning and colour of the text are preserved to the extent to which this is possible. The metre, which is somewhat irregular, consists of alternate lines of five and seven syllables—the following text of the first fourteen lines of the translation will serve as an example:—

Ukiyo to wa,

This “evanescent” (miserable) world, Taga ii-somete,Who first named it so? Asukagawa?O River Asuka. Fuchi mo chigiyô moSalary and estate. Deep places Seto kawari;Course of life how these change! Narrow channels Yorube ko-nami noOf me, Konami, his dependent: (a wavelet touching thy strand). Shitabito niTo his (Yenya’s) underman. Musubu, Yenya no Ayamari wa,The contract of betrothal (was allowed) but (there took place) the error of Yenya; Koi no Kasegui,The deep foundations of love; Kakogawa noOf Kakogawa Musume Konami gaThe daughter Konami, Ii-nadzuke,She was promised, Tanomi mo toradzu,But there was no giving or receiving of bridal gifts, Sono mama niUnder these circumstances, Furi-suterareshi,Shaken off and abandoned, Mono omioShe broods over things. - ↑ A stream near Kiyôto, flowing through flat land and constantly changing its bed. Hence the evanescent character of the banks amid which the river threads its way, and the propriety of Konami’s address to it.

- ↑ A pun on the speaker’s name, Konami, “child-wave,” “little wave.”

- ↑ Without which a marriage, or rather betrothal, is not looked upon as complete.

- ↑ A double pun here—“Kogoye” meaning: 1st, “to freeze, congeal”; 2nd, “the passage of a child.”

- ↑ They are travelling westwards, leaving Fusi-yama (more properly, Fuji-san) behind them. Fuji-san is, and probably always has been within historical times, completely extinct, so far, at least, as the summit is concerned. But the vapours that commonly wreathe or hover around its high bare peak often have the appearance of smoke or steam issuing from the long since cooled crater. The elevation of Fuji-san is close upon 13,000 feet above the level of the sea. The upper portion is covered with snow throughout the year, except from the end of July to the middle or end of September, when the peak is bare, though even during those months large masses of snow lurk in sunless clefts and crevices. No Japanese poet has omitted to celebrate the picturesque beauty of the mountain.

- ↑ Alluding to the custom, probably borrowed from China, of carrying the bride over a flame into her husband’s house.

- ↑ That is, “the plain of pines.”

- ↑ The Tôkaidô, “eastern sea-way,” the high road between the capitals of East and West Japan.

- ↑ A considerable town in the province of Suruga, some 90 miles westwards of Yokohama. It is now known as Shidsuoka, and is the present residence of Hitotsubashi, the last of the Shôguns. There is a curious word-play here, the sense of which I have endeavoured to give—suru ga fuchiu meaning in the common language, “the crowning of one’s efforts with success.”

- ↑ They are now supposed to be passing through a place called Oya shiradzu ko shiradzu, which name signifies “unknown to parent, unknown to child,” and involves probably some local story or tradition.

- ↑ Ohoi means “great,” “vast.” The River Ohoi is one of the largest in Japan, and the bed of it, at the point where a ferry carries travellers on the Tôkaidô across it, must be some hundreds of yards wide. But, except occasionally during the heavy autumn inundations, the stream is not much more than a hundred yards in breadth, occupying a sinuous channel in the middle of the dried-up stony bed of the river’s course.

- ↑ These are servants who tout for guests.

- ↑ What follows seems to be a portion of an ancient song, to be found, I believe, in the Shinzenden of Bakin, and as old, probably, as the time of the Ashikaga Shôguns.

- ↑ Kyomidzu. See ante.

- ↑ Otowa. This is a petty of water falling over the ledge of a rock in the grounds of the temple of Kyomidzu, supposed to have peculiar restorative qualities.

- ↑ Kwanon is the Buddhistic Venus, and like the hominum divomque voluptas, Alma Venus! of the great Latin poet, is regarded by some not only as the goddess of mercy, but as presiding over the continuous sustentation of the world and all its living creatures;

“per te—genus omne animantum

Concipitur, visitque exortum lumina solis.”She is the Avalôkitês’vara of Northern Buddhism, first mentioned in the Sutras of the fourth century after Christ. But Avalôkitês’vara was a male deity, and Eitel gets over the difficulty by supposing that the Buddhist apostles to China in the fourth and ninth centuries of our era, incorporated a native female deity (Kwanyin) having similar attributes with those of the Buddhist god, with the object of their own devotions. Kwanyin is said to have a disobedient daughter of Chwang of the Chow dynasty, B.C. 690 circiter. She was condemned to be beheaded, but the executioner’s sword broke, and she was put to death by being smothered. Her soul descended to hell, which thereupon became a paradise. But Yama, the Pluto of Buddhism, fearful of losing his kingdom, rejected her, and she reappeared upon earth in time to cure her father of an illness by cutting off the flesh of her arms. As a mark of gratitude he ordered a statue to be erected to her “with arms and eyes complete (tsien),” but by a misunderstanding of the word “tsien,” which means either “complete” or “a thousand,” the statue was made with a thousand arms and a thousand legs; and the goddess is often so represented at the present day, both in China and Japan. Vide Eitel, “Handbook of Chinese Buddhism.”

- ↑ Isé is supposed to be the favourite abode of the primeval gods of Japan, the chief of whom is the Sun-goddess, known commonly as Daijingû Sama.

- ↑ Narumigata, in the common language, may mean “the place of establishment of oneself.”

- ↑ A sort of small insect, making, by attrition of its wings, a somewhat pleasant sound, and for that reason often kept in bamboo-bark cages, and fed upon bits of cucumber or melon.

- ↑

Kirigirisu

Naku ya, shimo yo no

Samushiro ni

Koromo katashiki;

Hitori ka mo nen!I spread my garment on the ground

Whereon the night hoar-frosts lie,

Through the gloom pierces the shrill cry of the grasshopper,

In the chill solitude

How can I find repose on my lonely couch? - ↑ Sudzu is the name given to the string of bells generally hung round the tail of the animal. The pass of Sudzuka—Sudzuka-tôge—is of considerable height, but the traveller who climbs it is well rewarded by the succession of picturesque views it affords him.

- ↑ Allusion is here made to the old song—

“Saka wa teru-teru,

Sudzuka wa kumoru,

Aino-tsuchi yama,

Ame ga furu.”Which may be thus rendered—

“The sun shines fair on Saka’s peak,

While clouds veil Sudzuka’s summit bleak,

And Tsuchi’s top that lies between

Is through the shower hardly seen.”Saka, Sudzuka, and Aino-tsuchi are three conspicuous and contiguous hills, forming part of the range crossed by the Sudzuka-tôge, on which the phenomenon referred to is often observed during the showery days of early summer.

- ↑ Meaning, strictly, “the outflow of the waters,” but by a pun signifying “the mouths of all men,” that is, common report.

- ↑ Literally, “the stony place.”

- ↑ From which the finest view of Lake Biwa is to be had.

- ↑ Yamashina is the last village on the road, being close to Kiyôto.

The Ballad of Takasago.[1]

A wanderer’s staff he grasps now erst

On distant journey bent:

Must many a weary, weary day

On per’lous track be spent.

Tomonari.

“Of Aso’s shrine in Higo land,

Within broad Kiushiu’s sway,

The guardian, Tomonari, I;

Now list ye to my lay:

“Upon Miyako’s wondrous sights

I never yet have gazed,

And towards the royal city press,

To feast my eyes amazed.

“And by the way I fain would halt,

And turn a space aside,

Where Takasago’s famous strand

’Fends Harima from the tide.”

O he has girded up his frock,

Nor fears the distant way,

All eager the stately town to gain,

No longer will delay.

Well through the surf his bark is launched

Upon the sparkling sea,

O may fair spring winds waft him on,

Clear skies above him be!

Still o’er the wid’ning wat’ry waste

His course he presses on,

Beyond the dim, white, misty line

Where sea and sky seem one.

Beyond, and far beyond again,

And leagues still leagues upon,

His bark sails o’er the circling sea

Ere Harima’s shores are won.

O hoar and venerable Pine!

Thy swaying branches through,

With constant boom, the sweet spring winds,

And ceaseless murmur, sough.

While from the sounding shore below,

Where still the mists adhere,

The cadenced roar of the flowing tide

Delights the wanderer’s ear.

O ancient Pine! whose lofty top

With countless winters’ snow

Hath sparkled, is there wight alive

Thy birth or youth may know?

Amid thy topmost twigs behold!

The glitterings rime doth lie

Upon the crane’s rough-woven nest,

Ere yet the sun is high.

Each morn, among thy far-spread limbs

The winds soft greetings sing,

Each e’en, low murmuring farewells,

Through all this time of spring.

I well could rest beneath thy shade,

There commune with my soul,

And muse in silent loneliness,

While by the hours should roll.

For converse should I ever long,

And seek response from thee,

The rustle of thy wind-stirr’d leaves

Would softly answer me.

Lo! leaves and twigs the ground bestrew

And to my raiment cling,

I shake me free, with busy rake

The brown heap shorewards fling.

Takasago no Ura.

O far-famed Pine of Takasago!

How scarred thy wave-washed trunk!

The waves of time, too, on my brow

Have rippled wrinkles sunk.

Long, long have clung to thee, hoar Pine

These leaves now brown and sere,

With greenness aye renewed thou still

Thy leafy top shalt rear.