Chiushingura (1880)/Book 10

Book the Tenth.

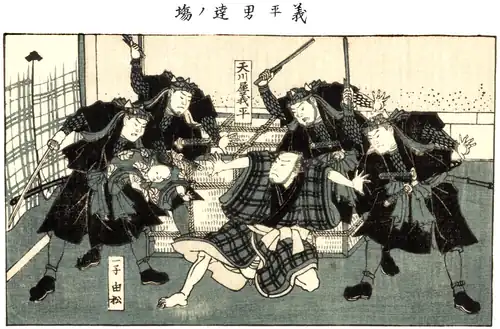

The Proof of Gihei.

nd so muttering to himself, Ryochiku went away.[1]

nd so muttering to himself, Ryochiku went away.[1]

It was past the hour of the hog,[2] and the night was dark, the moon being hidden by clouds, when a patrol of several men, iron mace and bundle of cord in hand,[3] and darkened lantern hanging at hip, crept slowly along one of the streets of Sakai, scanning each house closely as they advanced. One of the number went in front, like the dog scenting game for the hunter. Him the one who seemed to be chief of the patrol motioned to approach, and, as the former obeyed, whispered a word or two in his ear, to which the man immediately nodded an assent.

The party then stopped before a certain house, at the door of which the one who acted as scout began to knock vigorously.

“Who is there—who is that?” cried a man’s voice from within.

“Iya!” said the chief of the party. “I am master of the ship that arrived this evening. There is some error in the freight account—let me in, I must have a word with you.”

“You’re making a mighty fuss,” answered the voice, “about what is a small matter enough, I dare say. Can’t you let it rest till the morning?”

“Why, no,” said the first speaker, “the ship ought to get away to-night, and the account must be settled before she leaves.”

Fearing lest the loud tone in which his interlocutor spoke should awake his neighbours, the man of the house came to the door, and opened it, utterly unsuspicious of any trickery.

Hardly, however, had he pushed the door back, when two of the patrol threw themselves upon him, exclaiming:

“You are our prisoner! Do not attempt to move—we arrest you on authority!”

The remainder of the patrol then closed round their prey, and dragged him into the house.

“Kowa!” cried the prisoner, throwing his eyes round him in amazement. “What means all this?”

“What means this? Darest thou ask, villain!” exclaimed the chief of the patrol. “Thou art Gihei, art thou not—living at the sign of the Amagawa,[4] in this town of Sakai,[5]—and by order of Yuranosuke, a kerai of the late Yenya Hanguwan, hast got ready for him a quantity of arms and horse-gear, enough to load a good-sized ship with; which thou art about to send at one dispatch to Kamakura. Our orders are to arrest thee, and doubtless thou’lt be put to the torture—nay, thou canst not escape,—bind his arms, men.”

“This is a strange charge, sirs!” cried Gihei, for the prisoner was none other. “I know nothing whatever about what you accuse me of—you must have hit upon the wrong man!”

“Yah!” interrupted the chief. “Hold thy peace and make no noise, there is proof enough,—now, men!”

Upon this, his subordinates brought forward a travelling-box, wrapped in matting, that had been stowed on board that night, at the sight of which Gihei appeared somewhat disturbed.

“Stir not!” cried the chief to him, while the men rapidly undid the covering and were beginning to open the box, when Gihei, freeing himself by a sudden effort, kicked a fellow aside, and leaping upon the lid, took up a firm position.

“Yah, you ill-mannered boors!” he cried. “This trunk is full of articles ordered by a noble lady, the wife of a daimiyô, and contains various small things and warahi[6] books and objects, such as are kept in the secret drawers of armour-coffers, together with the letter ordering them all. If you open it, the name of a most illustrious and noble house will become public; and you must take the consequences upon yourselves, if you persist in disclosing it.”

“Ah! a likely story,” exclaimed the chief. “Thou hadst better confess the truth, without further trouble,—wilt not? Good!

“You know what you have to do,” added the chief, addressing one of his followers, who, with a gesture of assent, immediately left the room, and returned, after a few moments’ absence, dragging in with him a child, a little over a year old, the only son of Gihei, and called Yoshimatsu.

“And now, Gihei,” resumed the chief, “for the moment we won’t trouble ourselves about the contents of yonder box. You know that Yuranosuke and the other rônin of Yenya’s following have got up a plot against the life of Moronaho, of the details of which you cannot be ignorant. Reveal them to us and all will be well; refuse, and your boy here—you shall see what his fate will be.” Drawing his sword as he uttered the last words, the speaker placed the point against the child’s throat.

Gihei looked on unmoved, and said scornfully:

“Do you think you have to do with a woman or a child, that you hope to terrify me into making some confession by threatening me through the boy? You will find no coward in Gihei of the sign of the Amagawa. No fear for my child will make me say I know something, when I know nothing—nothing, I swear it by the lowest hell. If, however, you are simply enemies of mine, my boy there is in your hands, and if you choose to kill him I cannot help it.”

“Faith!” cried the chief admiringly, “you’re a stout-hearted fellow enough! Why, yonder chest contains spears, matchlocks, suits of chain-armour, etc., together with some forty-six devices for the use of the conspirators against Moronaho—and you dare to tell us you know nothing about all this! You would do better to end such talk, and make a clean breast of the whole matter. If you don’t, you will be killed by inches; hewed at, until your body is hewed into shreds. How like you that?”

“Do not think you frighten me,” cried Gihei, “with your threats. I deal not in weapons and armour only, but also in yeboshi caps for court and feudal nobles, in all sorts of things, in fact, down to straw sandals for servant lads and wenches. If there is anything unusual enough in that to need enquiry, everybody in Japan will be pestered out of their lives. If one is to be hewed in pieces, or scourged with the threefold cat, for following a trade, why, life is not worth having. Slay me, then; thrust your sword through the child’s throat! Why don’t you set to work upon me? Where would you like to begin—hew off my arm, or tear open my chest, or slash me on the shoulder or on the back?”[7]

As he uttered the last words, Gihei, quitting his position on the chest, made a sudden rush upon his captors, and snatched the child from their grasp.

The Proof of Gihei.

“You shall see,” he cried defiantly, “how far your threats are likely to influence me!”

The firm expression of his face shewed that he would not recoil from any extremity, and he seemed on the point of strangling his own child, when the lid of the chest was thrown open, and Yuranosuke, who had lain concealed in it, stepped suddenly forth.

“Yah!” cried the Karô, “hold your hand, Gihei, hold your hand!”

Filled with astonishment at this unlooked-for appearance, Gihei stood speechless, while the chief and the other members of the seeming patrol threw away their maces and bundles of cords, and, taking up a position at a little distance from their captive, assumed a respectful attitude. The Karô of Yenya, with a dignified and grave air, then advanced a step forward, and prostrating himself before the wondering Gihei, exclaimed:

“Sir, I hardly know how to express my admiration for you. Your devotion marks you out among the mass of men, as the brilliance of its flower reveals the lotus in the muddy marsh; as its glitter shows the grain of gold in the sand of the sea-shore. For my part, I knew well how loyal a heart was yours. The Karô of Yenya never for a moment doubted your fidelity, but to my comrades here you were a stranger, and some among them thought that since you were a Chônin[8] your fidelity ought to be proved; and would not rest until it was settled that you were to be seized, and your loyalty tried, by taking advantage of a father’s natural love for his child, and putting you to the proof—by threatening the life of your darling and only boy, unless you divulged our secrets. To show my comrades how brave and true a heart yours was, and to put these companions of mine at their ease, I have joined in the proof, though I knew what a cruel trial it would be to you. And now I do most humbly crave your pardon for what you have been made to suffer. They say that we Bushi are the bloom[9] of mankind, but never, never, has any Samurahi equalled you in generous devotion, and the hero who should withstand the onset of a thousand foes would display a courage inferior to what you have just revealed. Would that we could borrow your brave heart! With your noble conduct as our model, could we possibly fail in fulfilling our vengeance upon our enemy; even though he should betake himself to some precipice-fenced fastness in the mountains; or should enclose hinself within walls of iron and brass! Among men, true men are scarce, they say. Those that exist, it would seem, must be sought for among the ranks of the Chônin. For what you have done for us, if we did not bow down before you with reverent thanks, as before our village and household gods,[10] we should be wanting in gratitude to you for the favour you have shown us. ’Tis in the hour of need[11] that the hero reveals himself. Our lord, who is no more—alas, alas, how sad, how pitiable his fate!—had he known your true and valiant heart, would have advanced you to high military and civil rank,[12] and never would have repented him of his bounty. The eyes of my companions were blinded, as it were, to your worth; the courage you have displayed this night has acted like the infallible specific of some famous doctor, and they can now recognise your high qualities, thankful that you have caused the scales to fall from their eyes.”

Yuranosuke and his fellows then withdrew a little, thrice bowing their heads to the matting, and exclaiming:

“We humbly crave your pardon, sir, for our violence.”

“Nay, sirs,” cried Gihei; “I have done nothing to merit the honours you heap upon me; pray rise. The proverb says, ‘Judge a man as you do a horse—after you’ve tried him.’ And seeing that I was unfortunate enough to be unknown to you, it was necessary that you should put me to some proof. At first I was but a mean fellow; but since I have had the honour of transacting the business of your lord’s clan, I have become of some consequence. When I heard of the calamities that befell your noble chief, I shared your terrible distress. I racked my brains to devise some plan of exacting vengeance upon your lord’s enemy, but with no more success than a tortoise might hope for trying to strut,[13] like an actor, upon its hind legs. It was then that his honour here, Yuranosuke, came to me; and I did my best, without troubling my head about the consequences, to obey the commands I was favoured with. Oh that I were not a mere chônin! If I were a samurahi, were my rations no more than a handful of rice a day, I might have asked to be one of you, following humbly after you[14] in your enterprise. I should have been content if I could only have been allowed to draw water for your tea when wearied; but it could not be, mean chônin, O how mean! as I am; while you, sirs, by the favour of your lord, enjoy the distinction of wearing swords, and are permitted to devote your lives to his memory,—would that a like fortune were mine! At least, when in attendance upon your lord upon the dark path, you will not fail to let him know how gladly the fellow Gihei would have accompanied you!”

The companions of Yuranosuke, deeply moved by these earnest words, burst into tears, and ground their teeth in sympathetic rage, as they saw how bitter was the distress of Gihei at finding himself unable to give full vent to his loyal feelings. The Karô, however, restrained himself, and immediately addressed Gihei as follows:

“We shall leave for Kamakura to-night, and ere long[15] we hope to have achieved success. They tell me that you have gone so far as to send your wife away, in your care to preserve our secret. ’Twas well thought of, but you shall endure the discomfort of separation from her for a short time only; she shall soon be called home again. And now I must say farewell.”

“But let me wish you a fortunate issue to your undertaking in a cup of saké ere you start, sirs,” cried Gihei, as Yuranosuke prepared to depart.

“Nay, we must”

“Pray do not refuse me; here are hand-struck buckwheat cakes—they will bring you luck.”

“Hand-struck,[16] are they? lucky indeed,” cried Yuranosuke.

“Ohowashi and Yazama,” resumed the Karô, turning to his companions, “you two can remain with me; the rest of you may depart, and, picking up Goyemon and Rikiya on your way, get forward as far as Sadanomori.”

“Will your honour please to come this way?” said Gihei to Yuranosuke, and the two men who remained with him, after the rest had left.

“It would be rude to refuse you,” answered Yuranosuke, as, together with Ohowashi and Yazama, he followed his host into an inner room.

At this juncture a woman came up to the house—Sono, the wife of Gihei; who, either at the instance of her father Ryochiku, or by the will of her husband—she was puzzled between them, as one might find it hard to tell whether the moon, just above the horizon, was rising or setting—had been thrust out of doors.[17]

She was alone, and carried a small lantern in her hand, and as she knocked at the door she trembled with fear, confused with the pitch darkness and full of anxiety about her child.

“Igo, Igo,” she cried, after having knocked several times, “are you there?”

“What’s that,” muttered the servant-lad from within, in a sleepy tone, as he stumbled up out of bed, only half awake. “What’s that calling me—some wandering spirit or tricky goblin or other?”

“Iya, no. It is I, Sono, your mistress; open the door, quick.”

“Ah, but in spite of what you say I am rather frightened; you must not shout at me if I let you in,” cried the lad, opening the door as he spoke.

“Yeh!” he exclaimed, delightedly, as he saw Sono. “It is the mistress; I am so glad to see you back. Why, you are all alone—you might have got bitten by some wild-dog.”

“I might as well be, and die from the bite,” said Sono bitterly. “I can no longer endure this misery—banished from my own house.”

“I don’t understand you.”

“Is my husband asleep just now?”

“No.”

“Is he out?”

“No.”

“Well, then, where is he; what is he doing?”

“I am sure I don’t know. Just after nightfall, a lot of men came up here, shouting ‘caught, caught,’ like a cat might do that had just got hold of a rat; and when I heard the noise I covered my head with the bed-clothes and went to sleep. The men are now in the house, drinking saké, and enjoying themselves.”

“Strange! I wonder what my husband has in hand,” said Sono, half to herself.

“And baby,” she added, addressing the lad, “is he asleep?”

“Ay, he is fast asleep enough.”

“Has he been sleeping with his father?”

“No.”

“With you, then?”

“No, all alone; rolled up by himself.”

“Why, hasn’t he been nursed to sleep, then?”

“No; master tried, and so did I, but we could not give him any milk, so he did nothing but cry all the time.”

“Poor little fellow,” cried Sono, leaning against the door, and bursting into tears. “Of course, he would cry, what could he do else?”

Gihei, who was near, no more noticed her tears than heaven regards the patter of rain upon the earth beneath, and her sleeve was soon drenched with the flow.

“Ho, there, Igo, Igo,” he shouted, making his appearance and looking round. “Where is the fellow?”

“Here I am, sir,” said the lad.

“Blockhead!” cried Gihei, looking aslant at him, with a scolding expression.

“Go and wait upon my guests, yonder.”

Storming at the lad, the husband of Sono left the room, and was about to close the slide behind him, when his wife prevented him.

“Husband, husband, do not shut the door; I want so much to speak with you.”

“I can neither listen to you nor talk with you. You and your father, I find, are a pair of miserable wretches; away with you,” cried Gihei angrily.

“You take me to be like my father,” said Sono, “but I am not; look, this will prove it to you beyond a doubt,” throwing a paper, through the half-opened door, at her husband’s feet, as she spoke.

As Gihei stooped to pick it up, his wife made her way to his side.

“What is this?” exclaimed her husband, in a tone of astonishment; “’tis the letter of divorce I wrote some time since; I don’t understand your bringing it back.”

“You don’t understand my bringing it back—how can you say so?” cried Sono. “You know well enough how ill-disposed my father, Ryochiku, is towards you.[18] What could induce you to give that divorce-letter into his hand? As soon as he got back with it he wanted to marry me to some one else, there and then, to my utter astonishment. However, I put a good face on the matter, so as to lull my father’s suspicions, and watching my opportunity, stole the divorce-letter out of his pocket-book, and ran back home with it.”

“Surely you love your child,” continued the poor woman, with her tears flowing fast. “How could you be so cruel as to send me away, for him to hang at a foster-mother’s breast?”

“Oh!” cried Gihei, “the complaint comes from the wrong side, I think. Did you not heed what I said to you when you left, that I did not send you away for any fault of yours, but simply wished you to stay at your father’s for a short time, and could not give you my reasons because he was formerly a follower of Kudaiu, and I did not know which way his inclinations tended. I told you, too, to feign illness, and to put on an indisposed look night and morning, and neglect your hair, so that you might run no risk of being troubled with offers of marriage—for who would think of asking a woman to be his wife who neglected her hair? Why have you disobeyed me? And as to your child, Yoshimatsu, think you that you alone were distressed about him? During the day that lad Igo could coax and wheedle him into being quiet, but when night came he kept crying out continually for his mother, and however much we tried to pacify him by telling him his mother would be back soon he would not go to sleep, and when we sought to make him, by scolding or slapping him, or making faces at him, he did not cry, but whined and moaned so pitifully that I could hardly bear the sight of his misery. I now understood the force of the saying ‘your children will teach you how your parents loved you;’ and remembering how often I had behaved ill to my father and mother, I was filled with remorse, and wept almost the whole night through. Last evening, I several times took up the boy in my arms, with the intention of bringing him to you, and even got as far as the door with him, but recollecting that for you to have him for one night only would be of no use at all, and that I did not know in the least how long you might have to remain away from me, I thought it would make matters worse to take the child to you, and so walked about with him, dandling him and patting him till he at last fell asleep in my arms, when I lay down with him nestled close to me, and rolling his head about as he sought for the breast. I never intended to separate you from your darling for the rest of your life, but only for a short time, and, under the circumstances, I could not avoid writing the divorce-letter. Your father, Ryochiku, would never forgive me were I mean enough to get back the letter I gave him, in this underhand manner. I cannot receive it therefore, and you must take it back with you. The gods have decreed our union thus far; we must now be to each other as if the one of us had died.”[19]

As her husband ceased, Sono was silent for a moment. Knowing well the resolution of his character, she felt that he could not be induced to alter his determination, and when at last she found courage to speak, her tone was sad.

“How wretched a fate is mine! If I remain here I am in your way; if I go to my father’s house I shall surely be forced to marry again. Oh, husband, won’t you let Yoshimatsu be awakened, and brought to me for a few moments? Perhaps this is a last parting!”

“Nay,” replied Gihei, “to see him for an instant, and then to have to leave him, would but make the pain of parting from him harder than ever to bear. And now away with you—I have guests here to-night.”

“Let me see the child,” said the mother, “if only for a moment.”

“Come, come,” cried Gihei, soothingly, “have a little courage. Did you not hear what I said just now about the harm of seeing him, even for a moment only?”

And putting the letter into his wife’s hands, he forced her to the door, and, steeling his heart against her entreaties, pushed her out, exclaiming:

“If you really love your child, return to your father’s at once, and get him to afford you hospitality until the spring—when I hope I shall be able to come to some determination—if you will not do this, then all had better end between us.”

“Ah, if I could only be sure that my father would not force me into marriage with some one, I might bear the parting,” cried Sono, from without.

“Cruel husband!” she continued, “to send me away in this manner, who have done nothing wrong—not to let me see my child’s face even. How can you be so hard-hearted

“For pity’s sake,” she continued, knocking at the door, “open; let me have a look at him, even if asleep, just once, I entreat you with clasped hands, I beseech you; cruel, cruel!” and overcome with grief, she sank on the ground, and burst into tears.

“Ah,” she cried, after a time, collecting her energies, “I will restrain myself—I will say no more. Let my child but catch one glimpse of me, I know he will cry out ‘Mammy,’ and cling to me so that none can separate us. If I return to my father’s to-night he will force me into a betrothal ere a day passes. Oh, husband, what have I to live for? Adieu, husband, adieu for ever!”

The wife of Gihei, however, did not at once go away, but placed her ear against the door, hoping to hear her child’s voice, or perhaps that her husband might relent enough to let her have a look at him, but there was not a sound in the house.

“Alas, alas,” she cried, mournfully; “must I then go without one look at him!”

She turned to depart, when a couple of stout fellows, their faces concealed all but the eyes, suddenly blocked up her path. Ere she could utter a cry, they rushed upon her—was it not outrageous?—and while one of them held her fast, the other gathered her hair (which was dressed Shimada fashion) in his hand, and cut it off close to the roots, deftly possessing himself at the same moment of everything she had in her bosom.

The next instant the pair had vanished, no one could tell whither. Brutal ruffians they must have been, to attack a woman!

“Ah, wretches!” cried Sono. “Ah, villains! What means this violence? You have cut off my hair and seized the paper I had in my bosom; if you are common thieves,[20] why don’t you kill me at once?”

His manhood[21] roused by his wife’s cry of distress, Gihei could hardly refrain from rushing to her assistance, and the gnashing of his teeth showed the struggle that went on in his breast.

While the husband of Sono stood thus irresolute close to the door, Yuranosuke entered from the inner apartments, shouting out loudly for his host.

“Ah,” cried the Karô, as he caught sight of Gihei, “we are infinitely obliged to you for your kind and courteous hospitality; you shall have news from Kamakura—what other gear we may require I will let you know of by a swift messenger. And now we must bid you farewell—we should be on our way ere dawn breaks.”[22]

The Adventure of Sono.

“Well, sirs,” cried Gihei, “this is not an occasion on which I dare detain you; may your journey be a safe one, and may success attend your enterprise.”

“As soon as we get to Kamakura, we will send you tidings of us,” replied Yura. “Search as we may, we cannot find words in which fitly to express our heartfelt thanks to you for the services you have rendered us.”

“Yazama, Ohowashi,” continued the Karô, turning to his companions, “present Gihei with the parting gift you have ready for him.” The two men immediately stepped forward, one of them bearing an outspread fan, used for the nonce as a presentation stand, upon which was laid a paper parcel.

“We beg that you, sir,” resumed Yuranosuke, “and your wife, will deign to accept these trifling gifts from us.”

A cloud came over Gihei’s countenance. “I should not have put my neck in peril,” he cried, “simply to get a present from you, sirs. You despise me as a mere citizen, and think I shall be pleased by having my mouth filled with gold pieces.”[23]

“Nay, not so,” exclaimed Yuranosuke. “We are taking the last farewell of you we shall ever take in this world, where the gods have decreed that you should remain, and it is by desire of the Lady Kawoyo that we lay these poor gifts at your feet.”

“It is plain, sirs,” exclaimed Gihei, with increased vexation, “that you do not know me, and treat me with contempt. Your gifts are hateful to me,” spurning the fan away from him as he spoke. The paper packet opened out, as it fell to the ground, and its contents escaped. On seeing them, Sono uttered a cry of astonishment.

“Why, these are my comb and hair ornaments, and my hair that the men cut off just now.”

Gihei, meanwhile, had picked up the paper wrapping.

“And this,” he exclaimed, “is the letter of divorce I wrote! What is that about some one’s hair being cut off,” he added, turning to his wife—“whose hair?”

“I will explain,” said Yuranosuke. “I sent Ohowashi and Yazama here, round by the back of the house, to seize your wife and cut off her hair, so as to make her like a nun, which will prevent her father from forcing her to marry. Ere her hair grows again, I hope we shall have attained the object of our enterprise, and after our vengeance shall have been fully accomplished, you will be reunited—may you live long and happily together! Then you, lady,” addressing the wife of Gihei, “can take these ornaments, and, using these tresses as a cushion, dress your hair in the Kôgai[24] fashion—no one happier in the three kingdoms.[25] Only till then will you be, as it were, a nun. And however long it may be ere she be reunited to you, Gihei, we are all sureties for her that she will divulge nothing, and I myself, from the dark path, will act as intermediary in effecting your reunion.”

“How can I be sufficiently grateful for the favours heaped upon me!” cried Gihei. “Wife, wife, speak your thanks to his honour.”

“I can only say that I owe my life to you, sir,” said Sono, softly.

“Iya! I deserve no thanks,” replied Yuranosuke—“none whatever. And were Gihei not a citizen we should be overjoyed to have him with us. When we determined upon making our attack by night, our good fortune made us choose the name of your house, Amagawa, as our watchword. When we shall be within our enemy’s gates, ‘Ama’ will be our sign and ‘Kawa’ our countersign, and as we shout to each other ‘Ama, there,’ ‘Kawa, there,’ in the struggle, it will be as if Gihei were with us. And the first character of your name means ‘rectitude’ and the last means ‘level’; happy the omen, our

The Conspirators’ Farewell.

difficulties shall be levelled for us, and a complete success achieved! And now, again, farewell.” With these words, Yuranosuke rose, with his two companions, and the three then took their departure.

The fame of Yuranosuke’s deeds has come down to posterity, and the watchword “Ama” shall be “Yama.”[26] In the loyalty of his heart he found his tactics of Son and Go,[27] and the double-meaning language of the world tells us in his name how inexhaustible that loyalty was.[28]

End of the Tenth Book.

- ↑ The present book begins thus abruptly in the original. The following pages will make clear who Ryochiku was, and whence he went away.

- ↑ About half-an-hour after midnight.

- ↑ Usually carried, for obvious purposes, by policemen.

- ↑ Lit., “The Heaven-stream”—the name given by the Japanese to The Milky Way.

- ↑ A considerable seaport town, in the province of Idsumi or Senshiu.

- ↑ Vide Appendix.

- ↑ Allusion is here made to the practice of hacking at the dead bodies of criminals, by which the young samurahi was wont to perfect himself in swordsmanship, under the old order of things. Treatises exist upon this repulsive art—for an art it seems to have been considered—and one of the commonest of picture-rolls used to represent the various cuts, distinguished by special names, by practising which the aspirant could best learn on the dead subject to qualify himself for mangling the living one.

- ↑ There were two main divisions of society—excluding the priestly class and peasantry—in old Japan, the lines of demarcation between which are still far from being obliterated. These were the Bushi or Samurahi (lit., servers, like the Saxon “thegn”; then retainers and fighting men), originating in the soldiery of the early days of the Shôgunate; and the Chônin (lit., “street people”), or citizens and artisans. The first class had the right of wearing hakama (a species of wide, loose trowser), and of carrying two swords, a short one and a long one, in their girdles; the latter could only wear one short sword, and the ordinary kimono, resembling a dressing-gown, with hanging sleeves.

- ↑ Lit., “the wild-cherry blossom.”

- ↑ Vide Appendix.

- ↑ Lit., “’tis not in peaceful times that the hero reveals himself.”

- ↑ Vide Appendix.

- ↑ Lit., “strut about” with the conventional, and, to Europeans, ridiculous gestures of a Japanese tragedian.

- ↑ Lit., “following close at your sleeves, and at the hem of your garments.”

- ↑ Lit., “in not more than one hundred days.”

- ↑ The Japanese word translated “hand-struck” means also an attack or encounter.

- ↑ This portion of the text is disfigured by numerous word-plays, and a general rendering of the meaning is all that has been attempted.

- ↑ Ryochiku was a doctor, in the service of Kudaiu, and a man of mean and parsimonious character. Dissatisfied with his son-in-law, on account of the latter’s connection with Yuranosuke, as well as by reason of certain pecuniary transactions on the occasion of the marriage, in which the doctor conceived himself to have been ill-treated by Gihei, he had done his best to annul the union with his daughter. Gihei, on the other hand, fearful of Yuranosuke’s secret being betrayed, through Sono, to Ryochiku, with whom he had had an interview just before the arrival of Yuranosuke and his party, had sent his wife home, under a letter of divorce, which, however, he intended to be of only temporary force: so that she might be out of the way until Yuranosuke’s designs had been successfully carried out.

Such is the explanation generally given of the conduct of Gihei on this occasion, but in the text followed in the present translation the reader is rather left to infer, than expressly told, by what motives the husband of Sono was actuated.

- ↑ In the tenth month of each year, the God Iyahiko is supposed to assemble the eight hundred and more remaining gods at the yashiro or shrine near Namiki in Idsumo, where all the varying destinies of men, their deaths, births, marriages, &c., are arranged for the ensuing year. The gods being thus absent from their usual abodes, the tenth month is called “Kamina-dsuki,” or “godless month,” during which the Japanese avoid forming new connections.

- ↑ Lit., “robbers of combs and hair ornaments.”

- ↑ Vide Appendix.

- ↑ Lit., “ere night opens,” i.e., grows clear.

- ↑ Lit., “by having Koban ears clapped on my cheeks.” The Koban was a gold coin of an oval shape, and about the size of a human ear, value nearly five shillings.

- ↑ In which the hair is kept in place on either side of the head by a comb.

- ↑ Japan, China, and India.

- ↑ Probably the Buddhic “Yama,” the “heaven of perennial light,” is meant.

- ↑ Vide ante.

- ↑ The puns in the text render anything like a literal version of the passage impossible. The name of Yuranosuke’s prototype was Kuranosuke (see Appendix), and “Kura” signifies “a storehouse, magazine, treasury, &c.”