Chiushingura (1880)/Book 7

Book the Seventh.

The Discomfiture of Kudaiu.

he Gi-on Street in Kiyôto was crowded with pretty girls, flitting hither and thither, a very Paradise of Amida, beauty upon beauty showing their dazzling charms, bewildering and staggering the dullest and dreamiest of the passers-by.

he Gi-on Street in Kiyôto was crowded with pretty girls, flitting hither and thither, a very Paradise of Amida, beauty upon beauty showing their dazzling charms, bewildering and staggering the dullest and dreamiest of the passers-by.

“Hallo, there!” cried Kudaiu, making his way through the throng, followed by Sagisaka Bannai, to the entrance of Ichimonjiya, the teahouse of Ichiriki; “no host here? host, host”

“Wait a moment, whoever you may be,” cried a voice from within. “Who are you?” the voice continued, after a pause, the speaker opening the gate as he uttered the last words. “Yeh! what,—Ono Kudaiu, can it be your honour! with a gentleman too; pray enter, sirs, pray enter.”

And the servant—for the speaker was none other—bowed respectfully as he spoke.

“Iya!” exclaimed Kudaiu; “this gentleman comes here with me for the first time. You seem to be deuced busy just now, but I suppose you can let us have a room where we can have a quiet drop together.”

“Plenty of rooms,” replied the servant, “but a rich gentleman named Yuranosuke has had a fancy to get together all the best known women of the place, and occupies the whole of the ground floor; however, there is a small room at your service.”

“Full of dirt and cobwebs, I dare say.”

“Still as sharp-tongued as ever.”

“Sharp-tongued? no, but I am getting old, and must look out lest I become entangled in women’s webs.”

“At least you are as pleasant a gentleman as ever. Well, I can find you a good room upstairs.—Hallo, some of your there,” continued the servant, calling loudly for attendants; “light a fire, bring saké cups and tobacco, quick, pipes and bon…n…n…n;” uttering the last word in a loud ringing tone, that chimed in well with the ding of samisen and drum that came from the apartments were Yuranosuke and his crew of laughing girls were revelling. “What do you think of all this, Bannai?” cried Kudaiu, turning to his companion. “You see how Yuranosuke spends his time.”

“Well, sir, the man must be crazy, I think. Your private letters to my lord hinted at something strange about him, but my master had no idea things had come to this pass. I was ordered to come here and make inquiries, and if I saw anything suspicious I was to send word at once; but, faith, it is clear to me that I shall have my trouble for my pains. His son, that lout Rikiya, by-the-bye, do you know what he is about?”

“The lad seems to show himself here occasionally,” replied Kudaiu; “a couple of dissipated scoundrels they are, ’twill be strange if they don’t come to harm! What I am here to-night for is to try and find out if there is anything at the bottom of it all. Speak low, speak low, and come upstairs with me.”

“I follow your honour.”

“Well, then, come.” *******

“False, false your heart, I know it well,

You swear you love me, love me, while

Your lips a flattering tale do tell,

Your heart is ever full of guile.”

So sang a voice within, as Kudaiu and Bannai made their way to an upper story.

Meanwhile Yazama, accompanied by several other clansmen of Yenya, came up to the tea-house.

“Senzaki, Kitahachi, sirs,” he cried, “this is the place where Yuranosuke, our chief, passes his time; it is called Ichirikiya. Ha! Heiyemon,” addressing one of his companions, who seemed to be the follower rather than the equal of the rest, “you can remain in the servants’ quarters; at the proper time I will send for you.”

“I am much obliged to your honour,” said the latter, hurriedly; “I venture to ask your honour to do your best for me.”

Heiyemon then withdrew.

Yazama, knocking at the side entrance, now asked for admission. A girl’s voice answered from within, exclaiming: “Ai, ai, there—who are you, what is your name?”

“Iya!” cried Yazama, as he entered with his comrades; “go and tell Sir Yura that Yazama Jiutarô, Senzaki Yagoro, and Takemori Kitahachi are here, and desire to speak with him. Tell him we have sent messenger after messenger praying him to return, but without success, and we have therefore come ourselves to see him and talk over matters.”

“I really am afraid, gentlemen, that you have taken all this trouble for nothing,” cried the girl; “for the last three days his honour has been feasting and drinking, and has got into such a muddled and confused state that it will be some time before he is himself again.”

“Can this be true?” cried Yazama: “however, never mind, give the message all the same.”

The girl, nodding assent, obeyed; and Yazama, turning to one of his companions, continued: “Did you hear what the girl said, Senzaki?”

“I did,” replied the latter, “and she astonished me not a little. I had heard something of our chief’s dissipation, but thought it was merely put on to lull our enemy into a false security. But this looks like reality; he seems to have given himself up entirely to pleasure. I cannot make it out at all.”

“You see it is just as I told you,” broke in Kitahachi. “Yura’s disposition seems to have completely changed; the best thing we can do will be to rush in and slay him on the spot.”

“No, no,” cried Yazama, “let us have some talk with him first, and then”

“That will be best,” chimed in Senzaki, “and therefore we must wait here a little until the girl returns.”

Just then, Yuranosuke, with his eyes bandaged, appeared, staggering towards where the three rônin were standing, and surrounded by a number of girls, with whom he was enacting the part of devil in a game of blind man’s buff. “This way, devil, this way,” cried the girls, shouting with laughter as they frolicked about the drunken fellow. “This way, where you hear our hands clapping.”

“Caught, caught.”

“Not yet, Yura, not just yet, devil.”

“When I do get hold of one of you, I’ll make her gulp down a good draught of saké; she shall have a good pull, I promise you; ha! I’ve got some one,” seizing Yazama as he spoke; “bring the saké pot, quick, quick.”

“Iya,” cried Yazama, disengaging himself; “Yuranosuke, I am Yazama Jiutarô, don’t you know me? what can all this buffoonery mean?”

“Namu sambo,” muttered Yuranosuke; “I have done, the game is all up now.”

“What kill-joys those great hulking fellows are, Sakaye-san,” said one of the girls; “samurahi, I suppose, friends of our Yuranosuke!”

“I suppose they are,” was the reply; “a horrid-looking trio, too.”

“Pray excuse us, ladies,” broke in Yazama, “we have some matters to talk over with this gentleman, and we must ask you to be good enough to leave him with us for a little time.”

“Of course,” cried a number of the girls together, “we knew you

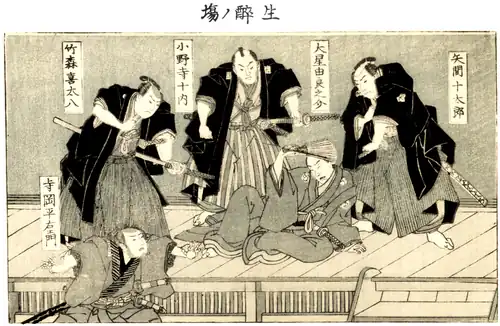

The Game of Blindman’s Buff.

would want us to go; well, we are off—Yura, you will come back to us soon.”

Having thus got rid of them, Yazama turned to his chief, who had lain himself down on the matting in an apparent stupor, and said:

“Yuranosuke, I am Yazama Jiutarô.”

“And I am Takemori Kitahachi,” added one of his companions.

“I am Senzaki Yagoro,” exclaimed a third samurahi. “Pray rouse yourself, we should be glad if you would listen to what we have to say.”

“Ah!” cried Yuranosuke, rising with a surprised air, “quite a number of you—you are heartily welcome, I am sure, but what have you come for?”

“We have come to learn,” interrupted Yazama, “when we are to start for Kamakura.”

“Start for Kamakura? That is a tremendously important matter, to be sure; what does that Tamba verse-maker—Yôsaku, I think they call him—say,

‘Away, away, to Yedo, we’

I beg your pardon, I am sure, I hardly know what I am talking about.”

“Yah!” exclaimed the three, simultaneously, “you’ve drunk yourself stupid; come, we will try if we cannot recall you to your senses.” And, drawing their swords, they were on the point of falling upon their thief, when Heiyemon, who had just come upon the scene, threw himself between them and his master.

“Stop,” cried the faithful follower, “put up your weapons. I must ask pardon, gentlemen,” he continued, “for interrupting you; mean fellow though I be, I must implore you to restrain yourselves for awhile. Your honour,” he added, turning to his chief, “I am the fellow Heiyemon, saving your respect; I hope I see your honour in good health.”

“Pfuh—Teraoka Heiyemon, is it? Ah! I remember you; you were sent northwards with letters lately; a quick-footed soldier enough, I see.”

“Just so, your honour. While up north, I heard of the self-dispatch of our lord. Namu sambo! I turned my steps homeward without a moment’s delay, but the news reached me, while journeying south, of the destruction of our lord’s house, and of the dispersion of the clan, and I was beside myself with grief and rage. Though a common soldier merely, I could not forget that I owed everything to our lord’s favour, and a burning desire to revenge the destruction of our house took possession of me. I went to Kamakura, and for three months lived in the greatest wretchedness, dogging Moronaho’s movements continually, in the hope of finding some opportunity of striking the fellow dead at a blow, but he took such care of himself that I could never get at him. In despair I thought there was nothing left but to commit self-dispatch, but then the recollection of my old parents at home prevented me, and I went to see them. On the road, I heard a rumour (perhaps it was dropped from the sun) that a plot was being set afoot to revenge our lord’s death,—your honour can imagine how delighted I was at the news; and, leaving everything behind me, I sought out the route of you gentlemen,” turning to the three rônin, “and followed you here, trusting that you would have the infinite kindness to listen to my humble request, and intercede for me with his honour for permission to add my name to the list of conspirators.”

“Ha!” cried Yuranosuke, “you’re quick of tongue, it seems, as well as quick of foot—you ought to be clown to some strolling company. As for me, my desire for vengeance is hardly strong enough to make me smash a flea, if I had an axe ready in my hand, to satisfy it; it would be strange, then, if I should take the pains to get up a conspiracy with forty or fifty comrades. Why, look you, if the plot failed, my neck would pay the penalty; if it succeeded, self-dispatch would inevitably follow; death any way. Where would be the use of seeking vengeance if I could not live to enjoy it?—one does not swallow jinseng medicine one moment to get strangled the next. Besides, you were but a common soldier, getting your five riyô a year, and three rations a day; why should you trouble yourself about our lord’s misfortunes? Your pay was hardly more than a begging priest’s dole of rice; for you to throw away your life in order to revenge Yenya would be as absurd as if a man were to give a high Kagura feast[1] in return for a morsel of laver. If you are bound to take one head, I, with my appointments of 1500 kokus, ought to take a bushel of heads at least. There need be no talk of seeking revenge, do you understand,—better do as the rest of the world. Come, tsu-tsu-ten, tsu-tsu-ten, don’t you hear the joyous note of the samisen? away, and make merry.”

“Your honour cannot be in earnest,” exclaimed Heiyemon. “My wage, true, was small enough, and your honour held a high post, but did we not both draw our livelihood from one and the same source? There is no question here of high or low. According to custom I know well enough I have no right to ask that the form of a fellow like me should be seen among you great gentlemen, but, oh! let your honour, though our lord’s representative, listen to my entreaty, and pardon my blunt speech! I am really nothing but an ape in the likeness of a man, ’tis true, still I implore you let me follow you; if only to tie your sandals or carry your burdens, take me with you; you cannot refuse me this boon, you…—ha! he has fallen asleep.”

“Asleep, aye, so he is,” cried Kitahachi, “miserable wretch. You need waste no further words with him; Yuranosuke may be looked upon as a dead man. Yazama, Senzaki, sirs, you now see what this brute’s real disposition is; shall we make an end of him, as was our intention?”

“Yes, yes,” responded his companions, “his fate will serve as a warning—upon him then.” They again laid their hands on their swords, but Heiyemon a second time interposed, and restrained them from giving way to their anger.

“Sirs,” exclaimed the foot-soldier, drawing near, “if you will carefully turn over the matter in your mind, you will see that Yuranosuke’s conduct may be explained. Ever since our lord was taken from us, His Honour has been harassed by the thought of vengeance upon our clan’s enemy, and none can know what cares have been heaped upon him, or what anxieties he has had to pass through, in the exact performance of the duties[2] devolving upon him. Look, too, how he has been compelled to bear in silence the contumely of men, and restrain his just indignation. If he did not, now and then, force himself to drink a bottle of saké, he would die, worn out with trouble and vexation. Wait till he wakes up, and you will see him again in his right mind.”

Yielding to the justice of Heiyemon’s address, the three rônin, attended by the foot-soldier, withdrew, and the good and evil of Yuranosuke’s conduct remained to be cleared up. ***** Now the waning moonlight began to merge in the breaking dawn, and Rikiya, breathless with the haste with which he had made his way from Yamashima, peeped through the paper screen, within which Yura was lying in a heavy sleep, and, fearful of rousing some of the other inmates of the house, gently approached his father’s slumbering form, and clashed his sword slightly. The Karô instantly rose to his feet, as if awakened by the clang of bridle-ring.[3]

“Yah, Rikiya,” he exclaimed, “the noise of your sword has awakened me; what need presses now? Softly, softly.”

“Here is a letter from the Lady Kawoyo, which I was ordered to bring to you without a moment’s delay.”

“Have you any verbal message to give as well?”

“Our clan’s enemy, Moronaho, has obtained permission to return to his lands, and in a few days will be ready to start. Details will be found in the letter.”

“Good. You can return home now, and at nightfall send me a kago; away with you.”

Rikiya bowed assent, and at once left the apartment.

The Dissipation of Yuranosuke.

Yuranosuke, eager to learn the contents of the letter, was in the act of opening it when Kudaiu appeared.

“Ha, Sir Yura,” cried the new-comer; “I am Kudaiu; I hope I do not intrude upon you.”

“Far from it,” replied Yuranosuke, concealing his vexation; “it is quite an age since we met; a good year at least, and we are older than we were, older than we were. But you are here to rub out the wrinkles in your forehead, no doubt? a sad dog, I fear.”

“Iya! Sir Yura,” replied Kudaiu; “one must not pick holes in heroes’ coats, they say, but to begin your enterprise by idling in a tea-house, careless of men’s blame—faith, it looks promising.”

“Ho,” exclaimed the Karô, “you are hard upon me, hurling words at me like stones from a catapult.”

“Now be frank with me,” broke in Kudaiu, “this dissipation of yours, you know, is a mere blind to cover your revengeful designs against Moronaho”

“Not a bit of it,” cried Yura, “obliged as I am to you for the idea. Here am I, over forty years old, and do you think I should run the risk of being twitted with hankering after girls, called an old fool, and laughed at as crazy, to cloak any such designs as you hint at? a pleasant notion to be sure!”

“Then you have really no intention of revenging the death of Yenya?”

“Not I; not a whit of it. When our lord’s castle and lands were confiscated, I spoke of dying upon our own ground, but this was merely to flatter the dowager. You remember you said that to fight with the government was the same as declaring oneself a public enemy, and so all at once left us to ourselves. Afterwards we talked a good deal of nonsense, but nothing came of it at all. Then something was said of committing self-dispatch at the tomb, but… we made our way out by the Rear Gate, and now, as you see, are anything but wretched, thanks to your example. Old friends must not forget each other, and so—take my advice—shiver the past, let it care for itself.”

“Ah!” said Kudaiu, “as I think of old days, I feel as wild as if I were changed into the fox Shinoda.[4] So let us have a draught, Yura; come, it’s long since we had one together; let me offer you a cup.”

“Willingly. Now for a bout.”

“Give me the cup; let me have a drain.”

“Here it is; drink.”

“Won’t you have a bit of fish with your saké?”

Kudaiu, taking a piece of cuttle-fish with his chopsticks from a dish beside him, offered it to Yuranosuke, who accepted the morsel, exclaiming:

“Ah, a bit of the creature who salutes by throwing out his hands and carrying his feet to his head.[5] Thanks, thanks.”

Yuranosuke had lifted the morsel politely to his head, preparatory to swallowing it, when Kudaiu seized his arm, saying:

“How! Yuranosuke, on the eve of the anniversary of our lord’s death, have you the heart to swallow that piece of cuttle-fish?”

“Why shouldn’t I, why shouldn’t I? Have you heard that our master, Yenya, has been changed into a cuttle-fish? Yeh! what nonsense has got into your head. It was his stupidity that has made you and me rônin. We have all of us good reason to detest his memory; and as to fasting, I cannot see that we are in the least bound so to mortify ourselves for his sake. What a delicious morsel this is you have handed me!” concluded Yuranosuke, swallowing it at one gulp without changing a feature, and causing such astonishment to his cunning interlocutor that the latter could not utter a word.

“Ah!” resumed Yuranosuke, “it is but ill eating,[6] after all. I will order a fowl to be stewed; come, meanwhile, with me. Here, you women there,” he added; “sing, sing;” and beating time gaily with his feet, he continued, “teretsuku teretsuku, tsutsuten tsutsuten, keep up

The Device of Kudaiu.

the merriment there,” while he led the way, affecting a drunken gait, towards the inner apartment.

Bannai, coming down from the room where Kudaiu had left him, now made his appearance.

“It is clear enough, Sir Kudaiu,” he said, “that the man has no thought of vengeance in his mind, or he would have been careful not to eat flesh on the anniversary of our lord’s death. I shall inform Moronaho of this, and end his anxiety.”

“In truth,” replied Kudaiu, “it does not look as if anything was to be dreaded from such a fellow—and see!” he continued, pointing to a corner of the room, “he has left his sword there, plain proof that he is nothing but a spiritless brute; the blade is all red with rust as a rotten herring. We know the true character of the man at last, and need trouble ourselves about him no further. Ho, there! bearers, my kago here; quick, get in, Bannai.”

“Nay,” said the latter, “you are an old man; pray take it.”

“You will permit me, then,” replied Kudaiu, making as if to enter the kago, but deftly concealing himself under the raised floor.

“By-the-bye,” continued Bannai, “I have heard that Kampei’s wife, O Karu, is in the house; you remember her, Kudaiu, do you not?”

Surprised at receiving no answer, Bannai drew aside the blinds of the kago, and, looking in, was astonished to see nothing but a huge stepping-stone,[7] out of the court-yard.

“Kowa!” he exclaimed, “this is strange. Has Kudaiu met with the fate of the Princess Sayo of Matsura?”[8]

As he looked round with a perplexed air, he suddenly heard himself addressed by Kudaiu from beneath the flooring.

“Bannai, Bannai, this is but a device of mine. Just now, Rikiya brought his father a letter which has caused me some anxiety. I want to find out what its contents are, and as soon as I do, I shall let you know. Meanwhile, accompany the kago as if I were in it.”

“I understand, I understand,” answered Bannai, nodding his head, as he obeyed his companion’s directions.

Meanwhile Karu was inhaling the fresh air from an upper verandah close by, trying to dispel the fumes of the saké she had been drinking, and chase away the gloom that settled upon her, as she compared the simple life of her village home with that she was now forced to lead.

Presently Yuranosuke appeared and said to her: “I must leave you for an instant. I have forgotten, samurahi though I be, a valuable sword, and must away at once to fetch it. You can arrange the hanging pictures on the wall and put fresh charcoal on the hearth by the time I return.”

Re-entering the room where he had had his conversation with Kudaiu, he was surprised to find the latter had gone.

“Hearken how the childish voices,

Father, mother dear, repeat:

Now the wayworn spouse rejoices,

Wife and little ones to meet.”[9]

“Yah! what is that?” cried Yura, as the words fell upon his ear; “cease, cease.”

Then looking around for a light by which to read the letter Rikiya had brought him, he caught sight of a lantern hanging by a small doorway in a corner of the court, and went up to it. The dowager’s letter, which was about Moronaho, was a pretty long one, and it took the Karô some time to wade through it, crammed as it was, like all women’s epistles, with “and so-you-know’s”[10] and sentences turned upside down. Karu, who was looking down from above, thinking the letter might be from some rival, leant over the balustrade, straining her eyes in the vain attempt to make out what it was about. A way of satisfying her curiosity, however, suddenly suggested itself. She disappeared for a moment, quickly returning with a bright metal mirror in her hand, by the aid of which she managed to read the letter from beginning to end.

Meanwhile Kudaiu, who had all this time lain concealed under the flooring of the adjoining room,[11] by furtive glances at the long slip of paper[12] which Yuranosuke, not being a god, could not suppose was within the ken of other eyes than his own, and had allowed to fall upon the ground as he unrolled it, contrived, by the help of the moonlight, to make himself master of the contents of the missive, and further managed to tear off a portion, which he intended to keep as a proof. Just then a metal ornament fell from Karu’s hair upon the stones below, and Yuranosuke, startled by the noise, looked suddenly up, instinctively hiding the letter behind his back. A cunning smile crossed Kudaiu’s face, while Karu, confused at being detected, hastily shut up the mirror, exclaiming, “Is that Yura?”

“What! O Karu, what are you about up there?”

“Why, the saké you made me drink has overcome me, so I came out to see if the cool air would revive me a little.”

“Oh, you came out to see if the cool air would revive you, did you? Iya! O Karu,[13] I have something to say to you. I cannot say it to you up there, I might as well be talking to you on the bridge of Heaven;[14] come down to me, and you shall hear it.”

“You have something to say to me? Why, what can you want with me?”

“Come down, and I will tell you.”

“Well, I will go round by the stairs and come to you.”

“No, no; if you go round, some of the servants will get hold of you and make you drink more saké. Is there no other way?—ha! here is the very thing; see, you can come down this ladder.”

And seizing a small ladder that stood close by, Yuranosuke placed it against the eaves of the verandah.

“I cannot come down that way,” cried the girl; “I should be frightened, I know; I should be sure to fall.”

“There is no danger,” exclaimed Yuranosuke, “none whatever; you need not fear, a strapping girl like you.”

“Don’t be so silly; it is like being in a boat, I know I shall tumble.”

The girl, however, got upon the ladder, and began to descend, but very reluctantly. “Quick, quick,” cried Yuranosuke, “or I will pull you down.”

Frightened at his tone, she descended a few steps and then again hesitated. Irritated at her slowness, Yuranosuke sprang upon the ladder, and, seizing the girl, lifted her to the ground.

“What did you see from up there? tell me,” he added.

“See? Oh, I did not see anything.”

“You did, you did; tell me.”

“Why, what should I see?—the letter seemed to please you.”

“You read the whole of it from up there.”

“I have told you I saw nothing—you are troublesome.”

Yuranosuke, persuaded that she had read the whole, could not conceal his vexation. Karu, coming softly up to him, exclaimed: “What is it, Yuranosuke; what is annoying you?”

“O Karu, you know I have long loved you; I want you to be my wife.”

“Don’t say that; you know you are not speaking the truth.”

“Truth has come out of falsehood. I am now in earnest. Say yes, say yes.”

“No, I will not.”

“Why?”

“You are not in earnest; your ‘truth has come out of falsehood’ should be reversed. You have never wanted me, and now you only pretend to.”

“What if I purchase you?”

“Eh!”

“To show that I am in earnest, I will see the proprietor of the house at once.”

“I hardly know. I….”

“If you have a lover, I will assist you both afterwards.”

“If I could be sure of that—but are you speaking truly?”

“I am, on my honour as a Samurahi. Remain with me but three days, and then you shall be quite free.”

“I should like that immensely, but you are only joking with me.”

“Far from it; I will see the proprietor of the house, and make arrangements at once. Do not trouble yourself about the matter, but stay here quietly for a little time, until I return.”

“Well, then, I will do so; you may trust me.”

“Above all, do not stir from the place until I come back; you are mine now, you know.”

“But for three days only.”

“Of course, of course.”

The girl was overjoyed at the prospect held out to her, and loaded Yuranosuke with thanks, as he hastened away to fulfil his promise. As she stood there, full of glad thoughts, she heard some one singing

“All the wide world cannot show

Grief the like of mine;

Endless is the weary woe,

As for him I pine.”

“Yah! what is that? cease!”

“List’ning thro’ the lengthen’d night,

To the shore-bird’s[15] shriek;

Sad I mourn my lonely plight,

Sleep in vain I seek.”

And depressed by the words, she fell into a melancholy mood, in the midst of which she was surprised by the unlooked-for appearance of her brother Heiyemon.

“How! sister, is that you?” said the new-comer.

“My brother!” exclaimed the girl, in confusion, covering her face with her hands. “O, what a shameful thing, to be seen by you in this place!”

“Nay, sister, not so,” answered her brother, gently. “On my return from the Kuwantô,[16] I heard the whole story from our mother; ’tis for your husband’s sake, for our lord’s service, that you have been sold; do not be ashamed, sister, you have acted nobly.”

“O brother, your kindness has made me quite happy—but I have got something to tell you, that will gladden you too. This very night, a gentleman is to take charge of me from the proprietor; the offer was altogether a surprise to me.”

“That is most fortunate; who is he?”

“You know him very well; it is Ohoboshi Yuranosuke.”

“What! Yuranosuke has promised to take charge of you: is he really fond of you?”

“No, I don’t think he is; he has only treated me several times during the last two or three days. He says, afterwards he will let me join my affianced, and let me go to him if I like. I could not meet with a better chance, could I?”

“Does he know you are betrothed to Hayano Kampei?”

“No, he does not. How could I tell him? My being here might seem a shame to my father and my husband.”

“H’m! he seems to have become really a dissipated fellow. It looks very much as if he had given up all thoughts of revenging our lord’s death.”

“Nay, you are wrong there, quite wrong, I can assure you, brother; but—don’t speak so loud—listen.” And the girl whispered to him the contents of the letter.

“Are you sure that you read the letter correctly?”

“Yes, the whole of it. Afterwards, he came close up to me and began to joke with me, and at last asked me to let him take charge of me.”

“All this took place, then, after you had read the letter?”

“Yes; but why are you so solemn?”

“Ah! I understand it now. Sister, your days are numbered; you cannot escape. You must let me decide your fate.”

As the youth spoke, he suddenly drew his sword and aimed a stroke at his sister, who escaped it by a quick movement.

“Brother, brother,” she cried, “what have I done wrong? Both my betrothed and my parents are alive; they should punish me if I have done wrong, not you. But if Yuranosuke takes charge of me I shall soon see both Kampei and my father and mother again. It was the thought of that made me so glad,—brother, do not be angry with me, even if I have done wrong.”

And she clasped her hands in entreaty as she spoke. Her brother, flinging the naked blade away, threw himself upon the ground in an agony of grief, bending his head down to hide his tears.

“Poor sister!” he cried, “you do not know, you do not know—our father is no more. He was cut down and murdered, on the twenty-ninth of the sixth month.”

“Murdered! my father!”

“Aye, murdered. But that is not all. Oh, sister, try to bear the ill news; your betrothed, Kampei, whom you hope soon to rejoin, he too is gone; he has committed self-dispatch.”

“O, brother, it cannot be true! O me! O me! my betrothed Kampei, he too dead!—tell me, brother, it is not true,” she cried, clinging to the youth’s arm as she spoke, and bursting into tears.

“Too true, sister, alas! But it would be out of place to tell you the sad story just now. Our poor mother was beside herself with grief, and her tears flowed constantly as she spoke to me of our loss. She begged me not to say anything about it to you, lest you should weep yourself to death at the terrible news. And I should have still kept silence did I not know that you cannot now escape your fate. Yuranosuke is immovable where his duty as a loyal retainer is concerned. Knowing nothing of your relation to Kampei, he never had any intention of taking charge of you; still less did any thought of love for you cross his mind. The letter you read contained matter of great importance, and it is quite clear that he only wanted to get hold of you to put you to death, and so keep his secret. You know the proverb, ‘walls have ears.’[17] If the contents were to get abroad, even if not through you, your fault would still be as great. You were wrong to read a secret letter, and cannot escape your fate. Better to die by my hand than by that of some other man; and if I slay you, and tell our chief that, though you were my sister, I could not pardon you, as knowing what ought not to be entrusted to a woman, he will let me add my name to the list of conspirators, and I shall share with him the glory of the enterprise.”[18]

“What makes the meanness of my condition so intolerable is, that unless I show the world that there is in me what makes me superior to the mass of men, I cannot hope to be allowed to take part in our chief’s undertaking. You understand me, sister; give me your life, let yourself die at my hands.”

The unfortunate girl, sobbing, sobbing all the time, could not at first make any reply; mastering her emotion, however, by a strong effort, she at last exclaimed:

“Hearing nothing from Kampei, I thought he had used the money paid for me, and had set out to join Yura, and I was angry with him for not coming to say good bye to me first. Oh me! what a miserable fate is mine! Though ’tis wrong to say it, my father was old when he was murdered, while my husband was not thirty—that makes it so pitiable, so pitiable! Oh that I might have seen him once ere he died! Why were we not brought together? I knew nothing of their sad fate, and have never mourned for them, for my father and my husband, both now no more. O, what have I to live for! But I must not die by your hand, brother, or our mother will be angry with you. Let me end my life myself. You can still take my head, or my whole body if you like, and show one or the other in proof of your devoted loyalty.”

“Farewell, brother, farewell,” she concluded, after a pause, taking up the sword he had thrown away, and placing the point against her throat. At this crisis Yuranosuke suddenly came upon the scene. Perceiving how matters were, he hastily caught Karu’s arm, exclaiming:

“Patience, patience; this must not be.”

“Let go, let go,” cried the girl excitedly, while her brother stood by transfixed with astonishment at the unlooked-for appearance of his chief—“I will, I must die.”

“Ho, there,” replied Yuranosuke, forcing the sword out of the girl’s hand. “Brother and sister, listen to me. You have cleared away all doubt from my mind; you, sir,” turning to the brother, “shall accompany me to the Kuwantô, while your sister shall not die, but live, and duly mourn the dead.”

“Mourn them,” said the girl, “I will join them on the dark path,” trying to seize the sword as she spoke.

“Your affianced, Kampei,” exclaimed Yuranosuke, keeping a firm hold on the sword, “is one of us, but has not yet had the luck to slay a single one of our enemies; and now that he is among those who no more are, he will be at a loss what to say to our lord; but he shall be at a loss no longer. Look here.”

And jumping on the floor of the adjoining room, he thrust the sword between a division of the matting and through the planking beneath, piercing the writhing rascal Kudaiu, who lay hidden there, through the back.

“Drag the fellow out,” cried Yuranosuke, at last.[19]

Heiyemon flew to obey his chief, and, seizing Kudaiu’s blood-stained form, pulled the wretch roughly out.

“Yah!” cried the soldier, “that rascal Kudaiu? This is a piece of good luck, indeed”—flinging the miserable man down at his chief’s feet as he spoke.

Yuranosuke, to prevent his prostrate victim from rising, caught hold of his side-hair, and forced his head roughly back, exclaiming:

“Villain! Thou hast played the part of the vermin in the lion’s belly, who seek to destroy what gives them food and shelter. Well rewarded by our lord, and honoured by his especial favour, thou hast become a dog of a follower of his murderer, Moronaho; secretly informing the enemy of our clan of everything, true or not true, that thou couldest get wind of! Listen. Forty and more of us have left our parents, abandoned our families, and given our wives, with whom we thought to pass our lives, to be harlots, that we might take vengeance upon our dead lord’s enemy. Waking or dreaming, the scene of our lord’s death was ever present to us, our bowels were twisted with grief, and our eyes ever wet with tears. This very night, the very eve of our lord’s death-day—ah, what evil things I have been forced to say about him with my lips; but at least in my heart I heaped reverence upon reverence for his memory,—this very night was

Villainy Defeated.

if thou chosest to offer me flesh. I said nor yea nor nay as I took it, but O! with what shame, with what anguish did I, whose family for three generations have served the house of Hanguwan, find myself forced to let food pass my lips on the eve of my lord’s death-day! I was beside myself with rage and grief, every limb in my body trembled, and all my bones[20] quaked as though they would shiver in pieces. Villain that thou art, devil, hellmate” and twisting his hand more firmly in the wretch’s hair, the infuriated Karô dragged his victim roughly along the ground, and flung him heavily on the stones, exclaiming:

“Ho, there! Heiyemon, I left a rusty sword in yonder room; away with this fellow, and hew him in pieces with it; make his death a long and painful one.”

“So will I, my lord,” answered the soldier, readily; and fetching the weapon, he rushed upon his prey, and hacked at him until he was covered with wounds.

“Sir soldier,” cried the miserable wretch, endeavouring to creep towards his assailant, and clasping his hands pitifully. “Intercede for me, lady,” turning towards Kara. “I entreat you, ask his lordship to have mercy upon me.” Thus was the haughty Kudaiu reduced to seek the aid of a common soldier, to implore the assistance of one who in former days he would scarcely have deigned to see, bowing his head repeatedly in the extremity of his shameful agony.

“Stop, Heiyemon,” cried Yuranosuke, suddenly bethinking himself; “it might be awkward if we killed the fellow here; take him away with you, as if he were simply dead-drunk.”

He threw off his mantle as he spoke, and cast it on his half-dead victim, so as to cover up his wounds.

At this juncture, the partition was suddenly pushed back, and Yazama, Senzaki, and Takemori entered from the adjoining apartment. “Sir Yura,” they cried, “we humbly crave your pardon for our error.”

Yuranosuke, paying no heed to them, continued: “Heiyemon, this fellow is dead-drunk, take him to the Kamo stream yonder, and give him a bellyful of water-gruel; away with you.”

End of the Seventh Book.

- ↑ Vide Appendix.

- ↑ Lit., “Scrutiny of each tree and bush” (to see if an enemy were lurking there).

- ↑ Alluding to the saying, “Yûshi wa kutsuwa no oto de ne wo sam asu,” i.e., “at clang of bridle-ring the sleeping hero wakes.”

- ↑ One of seven celebrated fox-goblins. The other six were named Kurosuke, Reita, Sansuke, Osuke, Yatsuyama, and Kudsunoha.

- ↑ Alluding to the Japanese custom, which is just the reverse, of acknowledging a gift by lifting it to the forehead.

- ↑ Lit., “does not tempt one to eat.” Sakana, the common term for fish when used as food, originally meant anything eaten with saké, perhaps even simple vegetables (na).

- ↑ Such as are generally found in courtyards of Japanese houses, for use in wet weather.

- ↑ Said to have drowned herself from disappointed love; and to have been turned into a stone.

- ↑ Lit., “As one hears in childish tones, Father, Mother, the words tell of the return home of husband or wife.”

- ↑ Lit., with “mairasesoro’s.” In Japanese correspondence the word “gozasoro,” a polite epistolary form of the copula or substantive verb, is constantly occurring. For “gozasoro,” the expression “mairasesoro” (lit., to cause to come or go) is commonly used by women and others not well versed in the complicated mysteries of Japanese letter-writing.

- ↑ The flooring of a Japanese house is always raised above the ground, and is open, more or less, all round.

- ↑ A letter, if of any length, is always written upon a long, narrow slip of paper, which is afterwards rolled up and fastened in various ways.

- ↑ See Appendix. Names of women.

- ↑ See Appendix.

- ↑ Chidori, a small bird found in flights on sandy shores.

- ↑ The eight eastern provinces, of which Kamakura at first and afterwards Yedo were the capitals.

- ↑ “Kabe ni mimi, tokkuri ni kuchi,” walls have ears and bottles have mouths.

- ↑ It is hardly necessary to comment upon the cold-blooded and selfish ferocity here exhibited. But “Chiushin” was the supreme virtue of the samurahi of old Japan, and to it, just as to the nobler sentiment of patriotism among the ancient Greeks and Romans, all the tender feelings were required to be sacrificed.

- ↑ Yuranosuke, it is said, on rolling up Kawoyo’s letter, after Karu had been detected in reading it, found that a portion had been torn off, and, always mistrustful of Kudaiu, was led by this discovery to guess at the latter’s place of concealment. According to others, the Karô saw his former subordinate’s face reflected in the mirror, by the aid of which Karu contrived to make herself mistress of the contents of the dowager’s missive, at the moment when, startled by the fall of one of the girl’s hair ornaments, he looked up and caught her in the act of reading the letter.

- ↑ Lit., “my forty-four bones.”