Chiushingura (1880)/Book 1

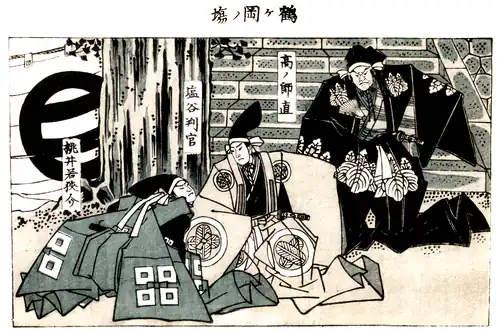

Tsuruga-oka.

Book the First.

What Happened at Tsuruga-oka.

fter the Shôgun of the Ashikaga dynasty, Taka-uji kô, had overthrown Nitta Yoshisada, profound peace reigned throughout the land. His Highness built a palace at Kiyôto, and the fame of his achievements penetrated into every corner of the empire.

fter the Shôgun of the Ashikaga dynasty, Taka-uji kô, had overthrown Nitta Yoshisada, profound peace reigned throughout the land. His Highness built a palace at Kiyôto, and the fame of his achievements penetrated into every corner of the empire.

All the people yielded to his authority, bowing down before him as the grass bends to the breeze, and the imperial might spread its protecting wings over the realm.

In commemoration of his success, the Shôgun caused a shrine to be erected to the War-God Hachiman at Tsuruga-oka, and sent his younger brother, Ashikaga Sahiyôye no kami Nahoyoshi kô,[1] to act as his deputy at the inauguration of the newly completed building.

Towards the close of the second month of the first year of the nengo Riyakuô (A.D. 1338), Nahoyoshi accordingly arrived at Kamakura, and was received by the Lord Moronaho, Count of Musashi, and chief representative of the Shôgun at the Eastern capital, a haughty nobleman, arrogant of carriage, and overweeningly proud of his position near the person of his august master; assisted by Wakasanosuke Yasuchika, younger brother of Momonoi, Lord of Harima, and Yenya Hanguwan Takasada, a baron of Hakushiu, charged by His Highness with the duty of receiving guests, and who were keeping strict ward within the curtain before the shrine. Nahoyoshi, taking his seat under the porch of the shrine, motioned Moronaho to a place on his left, while the two younger noblemen took up their position below the steps by the great maiden-hair tree there standing.[2] Pointing to a Chinese coffer, which the attendant had brought forward at his command, Nahoyoshi exclaimed:—“Among the helmets contained in this chest is one which belonged to Nitta Yoshisada, who was defeated by our brother Takauji, bestowed upon him by the Emperor Godaigo. Nitta, it is true, was our enemy; but he was a descendant, in the elder line of the Seiwa family, a Genji house, and it is commanded that the helmet worn by him should not be thrown aside, but placed in the treasury of the shrine.”[3]

“His Highness’s command surprises me,” cried the Count of Musashi; “Nitta, no doubt came of the Seiwa stock, but thus to honour a helmet worn by him, seeing that scores of feudatories of high and low degree claim like descent, is hardly, I submit, a prudent policy.”

“Nay, my Lord, not so,” said Wakasanosuke; “it seems to me that His Highness hopes in this way to obtain the submission of the disbanded partisans of Nitta without having recourse to force, trusting to the effect which his generosity in thus honouring their chief will have upon them. Your counsel is lacking both in wisdom and respect.”

The words were hardly out of his mouth when Moronaho exclaimed, angrily:—

“Yah! you dare to interrupt me and twit me, Moronaho, with lack of wisdom. Round the spot where Nitta was slain, forty-seven

The Audience of the Lade Kawoyo.

helmets that had fallen off the heads of their dead wearers were found; who shall tell which of them was Nitta’s? and if the wrong one should be thus honoured, what ridicule would be incurred! Away with you[4] for an overmeddlesome raw youngster.”

The colour mounted to Wakasanosuke’s face; but Yenya Hanguwan interposed.

“Kowa! your lordship is no doubt right. Still, what Wakasanosuke says is worth consideration. His Excellency, perhaps,” he added, glad to avert a quarrel, “will assist us.”

“Let the wife of Yenya be sent for,” replied Nahoyoshi, in answer to the appeal made to him.

A messenger was accordingly dispatched in quest of her; and after a short interval the Lady Kawoyo, the beautiful wife of the Hakushiu baron, presented herself. Her face was powdered, and the brilliancy of her appearance rivalled the lustre of a gem, as, with bare feet and long sweeping train, she modestly prostrated herself at a respectful distance from His Excellency.

“Lady Kawoyo,” said Moronaho, who was an admirer of the sex, “we are much obliged to you. His Excellency has commanded your attendance, pray come nearer,” assuming a soft manner as he spoke the latter words.

Nahoyoshi, regarding her, added:—“It is true that we have sent for you. Some time since, during the rebellion in Genkô (A.D. 1331), Godaigo Tenwô bestowed a helmet that His Majesty had himself worn upon Nitta Yoshisada at the capital, and the latter doubtless wore it upon the day of his death. It is supposed to be among the helmets I have caused to be placed in yonder coffer, but there is no one here who can pick it out. We have heard that the wife of Yenya was, at the time we refer to, one of the twelve Naishi, and if she can recognise the helmet in question we bid her to point it out.”

The Lady Kawoyo listened modestly to His Excellency’s command, and replied softly:—

“Your Excellency’s command honours me beyond my merits. Every morning and evening His Majesty’s helmet was in my hands, and I was present at the bestowal of it upon Nitta. Indeed, it was from my hands that the latter received it; accompanying his grateful acceptance with the following declaration:—‘Man lasts but one generation, but his name may endure for ever. When I go forth to battle I shall burn precious ranjatai perfume in the helmet thus graciously presented to me; and if I should die upon the battle-field, the foe to whom my head will fall a prize will know by the fragrance that he has taken the head of Nitta Yoshisada.’ ”

“Your answer, lady,” exclaimed His Excellency, as the wife of Yenya ceased speaking, “is sufficiently clear. Ho! there; take out the forty-seven helmets in yonder coffer, and show them one by one to Lady Kawoyo.”

The attendants hastened to obey; and, opening the coffer, brought out the helmets one by one. After a number had been examined, they came upon a five-fold helmet with a dragon crest, which the Lady Kawoyo immediately recognised by the odour still clinging to it, as the one bestowed upon Nitta by the Emperor Godaigo. The helmet thus identified was delivered to Yenya and Wakasanosuke, who were commanded to take charge of it, and see that it was duly placed in the treasury of the shrine. Nawoyoshi then rose and withdrew, followed by the two noblemen.

The Lady Kawoyo, thus left alone with Moronaho, addressed that nobleman with some embarrassment.

“My lord, pray excuse me. My duty being performed, and permission given me to retire, it would not be fitting that I should remain here longer. I beg, therefore, to take leave of your lordship.”

Moronaho, however, coming close up to her, detained her.

“Mâ, an instant, pray. Your duties to-day are over, and I venture to ask you to look at something I have to show you. His Excellency’s sending for you was a most fortunate thing for me,—just as if he were a god desirous of bringing us together. You know that I am fond of putting my thoughts into verse, and, day after day, I have asked Yoshida Kenkô to assist me in composing some lines to you, which were to have been sent to you. You will find them in this paper,” slipping a folded letter into her sleeve-pocket. “I hope you will look upon them favourably. You might give me your answer now, by word of mouth.”

The letter was addressed to the Lady Kawoyo—different enough in face and form from the Musashi stirrup,[5] from whom it purported to come. And the wife of Yenya, as she read the address, trembled with shame and confusion, yet feared to reproach Moronaho, lest disgrace should attach to her husband’s name. At first she thought of shewing it to her husband; but recollecting that it would only make him angry and might cause trouble, she simply threw the letter back without a word.

Moronaho picked it up, quoting a line from the Senzai collection—

“What thou hast spurn’d, is prized by me,

For hath it not been touch’d by thee!”

and continued to press his suit, hoping by importunity to compel a favourable answer—but in vain.

“Know you,” he cried at last, “that I am Count of Musashi? that on my will depends the weal or woe of the Empire? that your husband’s fate hangs upon your decision?—Do you hear me?”

Kawoyo could only answer with her tears, when Wakasanosuke opportunely returned, and, seeing that some insult had been offered to her, cleverly interposed.

“Lady Kawoyo, your duty is accomplished, and permission has been accorded you to retire. Ought you not, out of respect to His Excellency, to avail yourself of it?”—motioning her to withdraw as he spoke.

Moronaho saw that Wakasanosuke suspected something; and, determined not to show any weakness, cried angrily,

“Yah! again you dare to thrust yourself in my way. If the lady Kawoyo withdraws it is by my permission, not by yours. Kawoyo desires me, according to her husband’s secret wish, to instruct him how to discharge the duties of his office with perfect propriety, without which he would be helpless. And Yenya, though a Daimiô, seeks my aid; while you, a petty fellow who got your rank through the favour of nobody knows who, take care, and remember that a word from me will suffice to bring you into the clutches of the executioner.”

The colour mounted into Wakasanosuke’s face at this insolent speech, and he grasped the handle of his sword with force enough to crush it. Remembering that he was within the grounds of the Wargod’s shrine, and within the precincts of the palace, he had restrained himself when Moronaho had previously insulted him; but this last trial overcame his utmost patience, and he was on the point of making it a life and death quarrel, when His Excellency’s fore-runners came rapidly up, clearing the way with loud shouts for their lord’s passage.

In the confusion, Wakasanosuke was obliged to defer the hour, but still treasured the hope of vengeance. Thus, Moronaho, with a good fortune the reverse of merited, escaped destruction; and the next morning Yenya, ignorant of the ill-turn which his superior had played him, followed in his suite.

Nahoyoshi, meanwhile, returned at a slow pace to the palace, and his authority was everywhere reverently acknowledged; while his servants held their heads proudly erect, and the war-helmets were laid by arranged in peace-betokening order, according to the letters of the I-ro-ha.

Thus a profound tranquillity reigned in the land; throughout which, not to harm a head-piece became an universally observed rule.

End of the First Book.

- ↑ The Lord Nahoyoshi of the Ashikaga family, Commander of the left Imperial Guard.

- ↑ Still to be seen.

- ↑ I.e., As an offering to the God.

- ↑ Lit., “Draw in your head as a tortoise does.”

- ↑ Moronaho, as Lord of Musashi, had designated himself upon the cover of the letter as a Musashi Stirrup, Musashi being famous for the manufacture of stirrups.