Chiushingura (1880)/Book 6

Book the Sixth.

The Heroism of Kampei.

“All the old folks, hand in hand,

Haste to watch the joyous band,

Mingling in the harvest-dance[1]

’Neath the old folks’ kindly glance.”

uch was the country snatch the corn-threshers greeted the morrow’s dawn with at the village of Yamazaki,[2] which, as you will guess from the name, lay in the shadow of the hills. Here stood the mud and wattle cabin of Yôichibei, who tilled some few roods of land around; and it was here that Kampei had retired after his disgrace with his affianced Karu, who, up betimes, was combing out her disordered hair—of a truth, its dishevelled state seemed to show her indescribable anxiety for her lover’s return—and restoring to it its beautiful dark gloss, managing at last to arrange it so charmingly that it was a pity there were none but country boors to admire her.[3] As she finished her task, wishing she had a friend to talk over her fears with, her mother, leaning on a stick, came hobbling up the country path.

uch was the country snatch the corn-threshers greeted the morrow’s dawn with at the village of Yamazaki,[2] which, as you will guess from the name, lay in the shadow of the hills. Here stood the mud and wattle cabin of Yôichibei, who tilled some few roods of land around; and it was here that Kampei had retired after his disgrace with his affianced Karu, who, up betimes, was combing out her disordered hair—of a truth, its dishevelled state seemed to show her indescribable anxiety for her lover’s return—and restoring to it its beautiful dark gloss, managing at last to arrange it so charmingly that it was a pity there were none but country boors to admire her.[3] As she finished her task, wishing she had a friend to talk over her fears with, her mother, leaning on a stick, came hobbling up the country path.

“Ah, daughter, so you have finished doing your hair. How prettily you have put it up. Well, the wheat harvest is being gathered in, and you see nothing everywhere but people as busy as they can be. Just now, as I passed by the bamboo copse yonder, I heard the young fellows singing, as they threshed the corn, the old snatch—

‘All the old folks, hand in hand,

Haste to watch the joyous band,

Mingling in the harvest-dance,

’Neath the old folks’ kindly glance.’

Your father is long in returning; I have been as far as the end of the village to look out for him, but without seeing the least sign of him.”

“I wonder at that,” replied her daughter; “I can’t understand it; what can make him so late? Shall I run out and see if he is coming.”

“Why, no; young women cannot go wandering about all alone. Don’t you remember how you hated walking about the village when you were a little girl? and so we sent you to service at my lord Yenya’s; but now, our grassy moor seems to have drawn you home again. Ah, daughter,” after a pause, “if Kampei were but here your face would soon lose its anxious look.”

“Yes, mother, of course it would. When a girl has her lover with her, however dull and stupid the village may be, all seems joyous to her. And soon we shall be in the Bon month,[4] and then Kampei and we shall be the ‘old folks’ of the song, and go ‘hand in hand’ to see the dancing—shall we not? You don’t forget your own youth, mother.”

The girl spoke in a sprightly tone, wishing to spare her mother any anxiety, but her trembling limbs showed the distress she could not completely hide.

“Nambo; you talk merrily enough, but in your heart, in your heart”

“Iye, iye! mother,” said Karu, “I am not troubled. Is it not for my husband’s sake that I have engaged myself at the tea-house in the Gi-on Street at Kiyôto? I am quite ready to go; and it is only the thought that I shall not any longer be able to look after my father’s comforts that grieves me. My brother, who, though of mean condition, has been permitted to become a retainer of our lord Yenya, will be taken up by his duties”

Their talk was interrupted by the arrival of Ichimonjiya, the master of the tea-house in the Gi-on Street, accompanied by two coolies bearing a kago. “This is the place,” he cried. “Is this the house of Yôichibei?” he added, as he came up to the door, entering as he spoke.

“Pray come in, sir,” said the mother of Karu. “You have had a long journey, to be sure. Quick, daughter, bring the gentleman tea and tobacco.”

The two women were so anxious to please their guest that they would have covered the walls of their house with beaten gold, if they could have done so, to gratify him.

“Well, mistress,” said the master of the tea-house, “last night I gave your good man a vast deal of trouble. Has he got back all right?”

“Got back—did you say?” cried the mother of Karu. “Why, sir, has he not come back with you, then? What can this mean? Since he went to see you he has”

“Not come back yet?” broke in Ichimonjiya; “well, that is strange. Perhaps he has been carelessly passing by some shrine of Inari, and been bewitched by some crystal-pawing fox.[5] However that may be, here am I, come to take away the girl according to agreement. An engagement of five years for one hundred riyô; that was what we clapped hands on. Your husband said he had a pressing need of the money, and begged me with tears in his eyes to advance him half of the price, which at last, after he had sealed the paper, I agreed to do, bargaining that the girl should be given up on the payment of the remainder. He seemed beside himself with joy when I counted out the fifty riyô to him, and set out on his return there and then, although it was late, about the fourth hour (about 8 P.M.) I should say, and I warned him that it was unwise to travel by night with money about one. He wouldn’t listen to me, however, and hurried off. Perhaps he has stopped somewhere in the road.”

“But there is no place he would be likely to stop at, mother,” said Karu.

“Stop, indeed!” exclaimed the wife of Yôichibei, “he would be sure to hasten homewards with all speed. He would never rest until he had got back and gladdened us by the sight of the money. I cannot understand his being so long, at all.”

“Understand it or not,” cried the tea-house master, impatiently, “that is your affair; here is the balance of the purchase-money, and now I should like to take the girl with me.”

The fellow took fifty riyô from his bosom as he spoke, and offered them to Karu’s mother, saying, “This makes up the hundred riyô; come, take them, and let me have the girl.”

“But I can’t give her up,” cried her mother, “spite of what you say, until her father shall have returned.”

“But you must, you must, I tell you,” shouted Ichimonjiya; “why waste time? Look, here is the agreement with Yôichibei’s seal upon it—it speaks for itself. The girl is mine from this day, and for every day of her service I lose I will make you pay well. Go with me she must, and shall.”

Seizing Karu by the hand, he was about to lead her away when her mother interrupted him, catching her daughter by the other hand, and exclaiming, “Nay, nay, a little patience.”

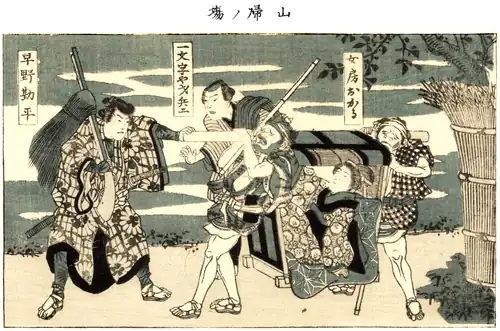

Ichimonjiya, however, pulled the girl towards him, and got her to the kago, in spite of her mother’s resistance. At this crisis, Kampei, with his straw cloak over his matchlock, suddenly made his appearance, and, seeing how matters stood, hastened into the house, exclaiming: What is all this about, Karu? tell me. What is this kago here for? Where are you going in it?”

“Ah, Kampei!” cried the girl’s mother, “I am so glad you have come. You are just in time.”

Kampei could not understand his mother-in-law’s delight. “There is some mystery here. Mother, wife, tell me, what is the meaning of all this?”

Further conversation was interrupted by Ichimonjiya, who strode into the apartment, and squatting down, exclaimed angrily, “O! let there be an end to this. You are my servant’s husband, are you?” turning to Kampei. “Husband or not, matters little to me. The agreement provides that no one (husband or other) shall prevent the contract from being carried out. See, Yôichibei’s seal is on the paper; is not that enough for you? Come, old lady,” he resumed, speaking to Karu’s mother, “let me have the girl without more ado.”

“Oh! son-in-law,” exclaimed the wife of Yôichibei, “what am I to do? Our daughter told us some time since you were in great need of money, and begged us to give her some for you; but how could we, poor folk, without a cash! At last, her father said the only way was to send our daughter for a time to service; but that this must be done without your knowledge, because he thought that perhaps you would not like money to be got in such a way. In case of need, you know, they say a samurahi may rob and steal;[6] and as it was for her husband’s advantage, there was nothing shameful in parting with her. So her father went yesterday to Kiyôto and settled terms with this gentleman here, the master of the house in the Gi-on Street, and ought to have been back ere this, but has not yet returned, which makes us feel very anxious about him. In the midst of our uncertainty this gentleman appears, and says that he gave half the hiring-money to Yôichibei last night, and has brought the other half with him, which he offers to us in exchange for Karu. I have asked him to wait until her father returns, but he refuses. What are we to do, Kampei?”

“Really my father-in-law is most kind,” said the youth. “I have had a windfall, but more of that bye-and-bye. There can be no doubt, I think, that Karu cannot be given up until her father shall have returned.”

“Cannot be given up,” cried Ichimonjiya; “and why not, I should like to know?”

“Well,” said Kampei, “this is Yôichibei’s seal, no doubt, and perhaps you really have paid the fifty riyô, but….”

“Iya!” broke in the tea-house master; “why, I could buy up all the women in Kiyôto and Ohozaka, for that matter; indeed, the whole population of Nyogo island;[7] and it is not likely I should say I had paid half the money down if I had not done so—is it? Besides, I can prove that I paid it. When I had counted out the money to the old fellow he wrapped it up in a cloth, which he was about to tie round his neck, when I showed him how dangerous it was to carry money in that way, and lent him a purse made of stuff just like my dress here, both in stuff and pattern. He tied the purse round his neck and started off at once.”

“What do you say,” broke in Kampei, “a purse made of striped cloth like this of which your dress is made?”

“Yes, yes, that will be proof of the truth of what I say, will it not?”

A terrible thought rose up in Kampei’s mind as he heard this, and he furtively but closely examined Ichimonjiya’s dress. His scrutiny convinced him that it was exactly of the same stuff and pattern as the purse he had taken the previous night, which was made of a sort of striped cotton cloth, shot with silken threads, and he could only conclude that the man whom he had accidentally slain was no other than his own father-in-law. “Would that the slugs had shattered my own breast-bone,” he thought to himself; “it would have been a less miserable affair than this.”

“Come, Kampei,” cried Karu, impatient at her lover’s silence, don’t stand there hesitating, but speak out and decide whether I am to go with this man or not.”

“Ah, well,” said her lover, “you see—what this man tells us seems to be true. There appears to be no help for it, and you must go with him.”

“What, before my father returns?”

“I forgot to tell you that I saw your father this morning. It is uncertain when he will return.”

“How! you saw my father this morning! Why did you not tell us, then, at once, and put an end to our anxiety?”

Ichimonjiya, taking advantage of the pause, exclaimed: “They say if you search for something seven times without finding it you may suspect some one. However, now we know where the good man is, we need trouble ourselves no more about him. So pray don’t let us be at sixes and sevens[8] any more about the girl, or faith, we shall begin to quarrel. Cheer up, all three of you; and if ever you, sir, or the old lady, should visit Kiyôto, I hope I shall have the pleasure of a call from you. Now, my girl, into the kago with you; up with you, quick.”

“Ai, ai,” cried the girl. “O Kampei, must I, then, go? I leave my father and mother to your care. You will not fail to be kind to them, will you? to my father especially, for he is very infirm.” The poor girl, of course, had not the least notion that her father was no more. Sad and pitiable situation! Kampei was on the verge of confessing everything upon the spot, but the presence of a stranger restrained him, and he was forced to endure his misery in silence.

“Son-in-law,” exclaimed the wife of Yôichibei, “you and your wife must now take leave of each other. It is a bad parting for you, daughter, but do not be faint-hearted.”

“Do not fear, mother. It is for my husband’s sake that I am sold into service for a time. I have no cause whatever to be unhappy. I

The Departure of Karu.

shall have plenty of courage—it is only going without seeing my father that troubles me.”

“Your father shall come and see you as soon as he returns, I promise you that. Take care of yourself, daughter; apply the moxa occasionally, and bring us back a healthy face. Have you all you want,—nose-paper and fan? Mind you don’t stumble and hurt yourself.”

The girl then got into the kago with her mother’s help, and the last farewells were exchanged.

“Ah me!” cried the wife of Yôichibei, “what ill-fortune has come upon us! why was the child born to such misery as this?”

The poor woman ground her teeth in an agony of distress, and burst into tears, while her daughter, grasping convulsively the sides of the kago, managed, but with difficulty, to stifle her sobs and restrain her tears so as to hide her grief. Pitiable sight!

The bearers now made a start, and the kago was borne rapidly away, the poor girl’s mother gazing after it wistfully.

“Ah!” she cried, “I have not comforted her at all; how wretched, how wretched!”

“Son-in-law,” she added, turning to Kampei, “you see I am her mother, yet I have forced myself to let her go. You must not let your grief overcome you. You spoke just now of my husband’s return being uncertain, and said you met him this morning.”

“Ha! did I?”

“Yes. Where was it you met him? where did you part from him?”

“Where did I part from him, you say? I think it was at Toba or Fushimi, or perhaps Yodo, or it might have been at Takeda.”

The words were hardly out of Kampei’s mouth, when a shuffling of feet was heard outside, and three hunters of the neighbourhood, Meppo Yahachi, Tanegashima no Roku, and Tanuki no Kakubei, immediately afterwards thronged the entrance, bearing on their shoulders a door, on which was laid a corpse decently covered with a straw rain-cape.

“As we came back from hunting among the hills last night,” exclaimed one of them, “we found the body of Yôichibei, who has evidently been murdered; and we have brought it here.”

Overwhelmed at the sight, the mother of Karu for a moment could not find speech.

“O, son-in-law,” she exclaimed at last; “whose work is this? who is the villain who has thus slain my husband? Son-inl-aw, son-in-law! been you must not rest until this cruel murder has amply avenged, amply avenged. O my husband! my husband!” Her complaints and reproaches were, however, of as little avail as the tears which flowed freely from her eyes. The hunters, shocked at the sight of her misery, exclaimed together, “Dame, dame, this is a terrible misfortune truly. But had you not better lay a complaint at once before the magistrate? A sad business, a sad business.” With which words they laid down the door with its burden upon the matting, and took their departure.

The mother of Karu, restraining her tears for a moment, marched up to Kampei: “Son-in-law,” she cried, “what can all this mean? The more I think the less I understand. Samurahi though you are, how can you look upon your father-in-law’s corpse without a start? You say you met him this morning. Did he not give you some money? Did he say nothing to you? Speak, speak! What, you have not a word to say? Ah! I understand, this explains everything.”

She thrust her hand suddenly as she spoke into Kampei’s breast, and dragging out the purse, continued:

“I saw you looking at this furtively just now. Ah! there is blood upon it,—it is you, you who have murdered my husband.”

“Iya! That purse is”

“That purse—ah! you thought your foul deed would remain hidden, but it is plain as sun at noon, in spite of you. You have killed him for the money that was in this purse—did you know for whom it was? Yes, of course you did, and murdered him because you thought he might not give you the whole of it, and hide some on his way back. Poor husband, poor husband! was it for this you sold your daughter? Wretch, we had always thought you a man of honour; and all the time you have been a villain,—oh! that I could kill you on the spot; you are a monster, not a man. The horror has dried up my tears, and I cannot weep. Alas! my poor husband! you little knew what a brute of a son-in-law it was in whose behalf, anxious as you were to help him to regain his position as a samurahi, you, an old man, gave up your rest and travelled by night and on foot to Kiyôto; gave up your treasure and your only daughter for one who sought to harm you in return for the good you were doing for him; like a dog that bites the hand that feeds him. Was ever such a vile crime dreamt of as this? Monster—devil. Give me back my husband, I tell you—bring him back to life!”

Blind with rage and grief, the poor woman threw herself upon Kampei, and seizing him by the side hair, dragged him towards her, buffeting him the while with all her might.

“Wretch,” she continued, “if only I had the strength I would hack you in pieces, though even that would not glut my vengeance.”

She went on loading him with reproaches, until at last, exhausted with grief and passion, she fell down in a faint; while Kampei, in an agony of remorse that made the sweat stand out upon his body,[9] threw himself upon the ground, gnawing the matting in his dread that the judgment of heaven had overtaken him.

Now two samurahi, wearing deep-brimmed bamboo hats that concealed their features, knocked at the entrance.

“Does Hayano Kampei live here? Hara Goyemon and Senzaki Yagoro desire an interview with him.”

Ill-timed as the visit of the two samurahi was, Kampei nevertheless rose to his feet, and, tightening his girdle, snatched up his side-arms and thrust them hurriedly in.

“He then went to receive his visitors, exclaiming: Well, well, gentlemen, who could have expected the honour of a call from you at this poor hut? I am sure I do not know how to thank you sufficiently;” bowing his head low as he spoke.

“But perhaps,” cried Goyemon, “we are interrupting you in some family engagement; you seem occupied.”

“Oh! nothing of any importance; some small private matter, of no moment, I assure you. Pray do not trouble yourselves on that point, but do me the honour to enter.”

“In that case,” cried the two samurahi, “we will accept your invitation.” And passing to the upper end of the apartment, they seated themselves upon the matting.

Kampei, kneeling before them with the palms of his hands upon the ground, exclaimed: “Lately I was absent from my lord’s side upon an important occasion; a failure of duty for which it would be vain for me to try to find any excuse. Nevertheless, I implore you to procure my crime to be pardoned. I entreat you, gentlemen, most earnestly I entreat you, to intercede for me, that I may be permitted to join with the other retainers of my lord’s household in honouring the anniversary of his death.”

As he spoke the unfortunate youth was overwhelmed with shame at the recollection of his fault. Goyemon at once replied:

“Listen. Though a rônin without resources, you have offered a subscription of a large amount towards the expense of erecting a monument to our dead lord. Yuranosuke has been informed of this, and is full of admiration of your conduct. The monument will be placed in the family burying-ground of our lord. But your disloyalty makes it impossible for our chief to receive your subscription. The spirit of our dead lord would be indignant with us were we to accept your money for such a purpose, and we have been ordered therefore to return it to you.”

As he concluded Senzaki drew forth from his bosom a paper packet containing the money which Kampei had thought himself so lucky in finding, and had shortly after handed to Senzaki, and placed the packet before the youth, who, wild with grief and despair at the ruin of all his hopes,[10] was unable to utter a word.

“Ha, villain!” cried the mother of Karu, weeping and pointing to Kampei; “you are now reaping your reward. Listen, gentlemen: this fellow’s father-in-law, a man stricken in years, but regardless of his age, sold his daughter into service for the sake of this wretch before you, who, lying in wait for the old man as he was returning home, murdered him and robbed him of the money. The deed was done in darkness, that none might know of it. Sirs, can you accept the assistance of such a man, a parricide, whom, if the gods and Buddha do not punish, they must surely be deaf to all entreaties. You see the wretch,—a son, a murderer of his father. Hew him in pieces, sirs, I implore you; for I am but a woman, and have not the strength to avenge myself with my own hands.”

Overcome with her feelings, the unfortunate mother of Karu threw herself, in a flood of tears, upon the ground, while the two samurahi, aghast at the tale, laid hands on their swords.

Senzaki, his voice choked by indignation, exclaimed: “Kampei, villain! you dared to come to us with your murderer’s booty in your hand. Is this the way to atone for your disloyalty? Inhuman monster! How dare you call yourself a samurahi?—horror. A parricide and a thief, you deserve instant crucifixion; and I should be well pleased to spit you with my own hands upon the tree.”

“Like the philosopher Kôshi (Confucius),” added Goyemon, “who declared that he would rather die of thirst than drink of the water of a fountain so ill-named as that of Tô-sen (i.e., the Fount of Robbers), so no man of honour could hold intercourse for a moment with such a wretch as you. How could you dream of offering us your ill-gotten gains for the service of our dead lord? Yuranosuke, with his rare sagacity, must have divined what a disloyal and treacherous nature yours was, when he ordered us to return you the money. Bloodthirsty wretch, your name will be handed down to posterity as that of the infamous Hayano Kampei, a retainer of Yenya. Idiot that you are, would not at least remember what disgrace you were bringing upon your lord’s house? had you not sense enough for that, at least? What devil can have got hold of you?”

Goaded by these reproaches into a kind of despair, his eyes fixed and overflowing with bitter tears, Kampei thought but one course was open to him, and suddenly throwing off the upper part of his dress, grasped his sword, unsheathed it, and with one stab gashed open his bowels.

“Alas!” he cried bitterly, “I dare not show my face again to men. As soon as I saw that my hopes were vain, I made ready for what was inevitable. As to the murder of my father-in-law, I will explain how this came to pass, so that the name of my dead lord may not be dishonoured. I pray you hearken to me, sirs. After I parted from Senzaki the other night, it soon become dark, and, as I followed a hill track, I suddenly disturbed a wild boar, and sent a couple of bullets after him. As I came up close, and bent over what I thought was the carcase of the animal, I saw to my horror that I had accidentally shot some wayfarer. I searched the dead man’s dress for medicines, and came upon the purse. Possibly I did wrong in taking it, but it seemed to me, then, as if it had been sent to me from Heaven. I immediately hurried away after Senzaki, and gave him the contents. When I got home, I found that the man I had slain was my father-in-law, and the money I had taken the price of my wife. Everything I do seems to fit in with the facts around me as ill as the two halves of an Isuka[11] fowl’s bill. An evil fate pursues me. Consider, now, I pray you, my situation.”

As he concluded, his bloodshot eyes became suffused, and he gave vent to his despair in a flood of tears.

Senzaki, as if struck by a sudden thought, rose up hastily, and began to examine the corpse. On lifting it, and turning it over, a large gash became visible.

The Distress of Kampei.

“Goyemon,” he cried to his companion, “come here. This at first looks like a gunshot wound, but it is really a sword cut. Kampei, you have been over hasty.”

The mother of Karu was so astonished by the discovery that she could not utter a word.

Goyemon, across whose mind a sudden recollection flashed, exclaimed: “Now I remember,—you too cannot have forgotten,—the corpse we passed on our road here, with a gunshot wound in it. We went up to it, and found it was the body of Ono Sadakuro, whom his father—that covetous wretch, Ono Kudaiu—tired of the fallow’s evil course of life, had turned out of house. We had heard that the son, not having a mat to bless himself with, had taken to highway robbery. Without doubt, Kampei, this Sadakuro was the villain that murdered your father-in-law.”

“What?” cried the mother of Karu, bending over the corpse and examining the wound, “Kampei then was not the murderer of my husband? O! son-in-law!” turning to the unfortunate youth, “I pray you with clasped hands to forgive me. I am but a silly, stupid old woman, and you will bear with me and pardon me for all that I have said. Kampei, Kampei, you shall not, must not die,” turning her face, streaming with tears, to him as she spoke.

“Now that what seemed evil in my conduct has been explained, mother,” cried Kampei, “I can face the dark path in peace. Soon I shall be with my father-in-law, and we shall climb the Shidé Hill and pass by the triple cross-way together.”[12]

Goyemon, interrupting Kampei, who had seized the sword which still remained in the wound with the purpose of hastening his death, exclaimed:

“Ah! Kampei, yet a little patience; without knowing it you have slain your father’s murderer. Fortune has not been all against you, and, by the favour of the Archer-God, you have been enabled to take a glorious revenge. But I have something to shew to you ere you die. Look here,” drawing a paper from his bosom and spreading it open before the dying youth; “at the foot of this is a list of the samurahi who have sworn to take the life of our enemy Moronaho.”

Goyemon began to read the paper, but Kampei, who felt his agony coming on, broke in, saying:

“Tell me the names of the conspirators.”

“We are forty-five in all,” replied Goyemon; “but now that I have come to know how truly loyal and devoted a retainer you have been, I shall add your name to the list, and I give you this paper that you may take it with you on the dark path, and reverently offer it to our lord Yenya.”

He then took an ink-horn from his bosom, and after writing down Kampei’s name, handed the paper to him, exclaiming:

“Seal it Kampei, seal it with your blood.”

Kampei obeyed, pressing his bloody hands upon the paper.

“I have sealed,” he exclaimed. “Comrades, I cannot thank you enough; you have enabled me to obtain what I most wished for in the world. Mother, do not grieve, my father’s death and my wife’s service will not now be of no avail. The money will be used by these gentlemen who have sworn the death of the enemy of our house.”

The mother of Karu, her eyes filled with tears, placed the packet with the purse and the money which Ichimonjiya had brought, before the two samurahi.

“Pray accept this purse as a token of my son-in-law’s share in your enterprise: and consider that his spirit is with you in your plot against your enemy.”

“We will; we will,” replied Goyemon, taking up the purse. “We will prize this purse of striped cloth as if it were full of barred Ôgon.[13] Sir,” turning to Kampei, “may the perfection of Buddha be yours.”

“Alas!” said Kampei, “the perfection of Buddha is not to be dreamt of by such a wretch as myself. The hand of death is upon me, but my soul will remain on earth that it may be with you when you strike our enemy.”

His voice was rapidly failing, and the mother of Karu, seeing the end was near, burst into loud lamentations.

“O! Kampei, Kampei! my daughter is away, and knows nothing of all this misery. If only she were here to look upon you once more ere you die!”

“Nay, nay, mother; let her know nothing of her father’s death, nothing of my death. She has gone to service for the sake of our lord Yenya; and if she were told of all that has occurred, she might neglect her duties, which would be like disloyalty to our dead chief. Let things remain as they are. And now,” he resumed, “my mind is at ease;” and thrusting his sword into his throat, he fell back and died.

“Son-in-law, son-in-law!” exclaimed the mother of Karu; “alas! alas! he is dead! Is there any one in the world so wretched as I? My husband murdered, my son-in-law, to whom I looked for support after my man’s death, a corpse before my eyes, my darling daughter separated from me, none but myself, a poor old woman, left,—why should I live all alone in the world? what have I to hope for? O, Yôichibei, Yôichibei, would that I were with you!”

Her sobs prevented further utterance for a time. At last, mastering her emotion for a moment, she struggled to her feet.

“Son-in-law, son-in-law,” she exclaimed, “take me with you;” and falling upon his body, she embraced it convulsively, the tears raining down from her eyes as she gazed now on the corpse of her daughter’s husband, now on that of Yôichibei, until at last, exhausted by grief and despair, she sank on the ground, unable to utter a sound.

“Come, mistress!” cried Goyemon, “do not grieve so much. I know it is very hard to bear; but it may comfort you if I tell you that I shall inform our chief Ohoboshi of the manner of Kampei’s death. You had better, keep this money, a hundred riyô in all. ’Twill buy a hundred masses—fifty for the repose of your husband’s soul, and fifty for that of your son-in-law’s; you will see that all the funeral rites are decently conducted. And now,” continued Goyemon, “we must take our leave of you. Fare you well, mistress.”

“Farewell!” repeated Senzaki.

The two samurahi then took their departure, their eyes suffused as they gave a farewell glance back, and the tears falling as they became lost to view.

End of the Sixth Book.

Satisfaction in Death.

- ↑ Misaki-odori, i.e., misaki-dance. Misaki is the name of a place near Kiyôto. Misaki means also the maturing of the ear, fruit or crop.

- ↑ “Before the Hills.”

- ↑ In this passage, the sense of which is given with considerable closeness, are various word-plays and a character-rebus, the explanation of which would be out of place in the present translation, and would, besides, require the use of Chinese signs.

- ↑ Vide Appendix, “Bon month.”

- ↑ The fox, much dreaded on account of his supposed influence over human beings, is generally represented as holding a crystal ball in his forepaws, without which he is said to be powerless.

- ↑ Allusion to the proverb, “Kiritori gô-tô-wa, bushi no narahi,” i.e., Slaughter and rapine, samurahi’s daily deeds.

- ↑ Vide Appendix.

- ↑ Lit., at fours and fives.

- ↑ Lit., “Throwing off boiling hot sweat in his distress.”

- ↑ Lit., “Felt his senses turned upside down.”

- ↑ Which are of unequal lengths.

- ↑ Vide Appendix.

- ↑ Vide Appendix.