Chiushingura (1880)/Book 11

Book the Eleventh.

Retribution.

hat the soft may overcome the hard, the weak may overcome the strong, was the secret revealed by Sekikô to the hero Chôryô.[1]

hat the soft may overcome the hard, the weak may overcome the strong, was the secret revealed by Sekikô to the hero Chôryô.[1]

Ohoboshi Yuranosuke, the liegeman of Yenya Hanguwan Takasada, mindful of this maxim, got together his fellow-plotters, forty odd brave fellows, and, embarking with them on board a couple of fishing-boats, in which they lay concealed under straw mats, started for Cape Inamura,[2] in the neighbourhood of which they hoped to find their landing as little guarded against as their enterprise was unsuspected by their enemy.[3]

They arrived in safety at Cape Inamura, and as the first boat was brought alongside a huge rock on the beach, Yuranosuke leaped ashore, followed by Hara Goyemon, after whom came Rikiya, succeeded by Takemori Kitahachi, Katayama Genta, and others. From the next boat there landed in regular order, Kakuyama Magoshichi, Sudagoro Katsuta, Hayami, Tomonori, the famous Katayama Gengo, Ohowashi Bungo, carrying a huge wooden mallet, Yoshida, Ohokazaki, Kodera, and others, Kowase Chiudaiu, holding under his arm a number of small bows, the renowned Ohoboshi Sehei, and others, including the eldest son of Kodera, rising up together like the lift of the morning mist, Shinoda and Akane, carrying halberds aloft, with Nogawa, armed with a cross-bladed spear, while several men provided with ladders brought up the rear. All wore mantles bearing for devices different letters of the “Iroha”—a different letter for each man.[4] Yuranosuke, not in the least dissipated now,[5] had caused his aide, Yazama, to bring with him a number of eight-foot bamboo poles, for the purpose of putting the plan of forcing open the shutters I have already described, into execution. At a little distance behind his chief, followed, humbly enough, Teraoka Heiyemon. In all, the party consisted of forty-six men, wearing for device each a letter of the alphabet on their sleeve, chain-armour on their thighs, on their breast the cuirass of loyalty—of a truth, a lesson-book, as it were, of the alphabet[6] of faithful duty.

“Comrades,” cried Yuranosuke, turning to his companions, “do not forget the sign and countersign, ‘Ama’ and ‘Kawa,’ the names of Gihei’s house. As has already been settled, Yazama, Senzaki, Kodera, and their party, headed by my son Rikiya, will make their way in by the front gate, while Goyemon, with myself, will press round to the rear entrance. At the right moment, a loud whistle will be heard—let every one then rush to the attack; there is but one head we have to take.”

The men listened respectfully to their chief’s command, and as they came in sight of their enemy’s castle their eyes were ablaze with fury, while, filled with hatred of their foe, they separated into two parties, one to attack by the rear, the other by the front gate.

The great lord of Musashi, meanwhile, his suspicions lulled by the account he had received of Yuranosuke’s dissipated life, spent his time in drinking and debauchery, assisted by the wretch Yakushiji,[7] whom he had taken into high favour.

On this very night, exhausted by his excesses, the murderer of Yenya had only just fallen asleep, when Yuranosuke and his party approached the castle. A profound stillness reigned, broken only by the occasional rap-rap of the clappers of the sentinel going his rounds.

The plan of attack having been finally settled between the two parties, Yazama and Senzaki, like a couple of bold fellows as they were, crept up to the front gate, and, peeping through a chink, took a survey of the interior. As soon as the faintness of the sound of the clappers showed that the sentinel or watchman was pretty well at the farther end of his round, they caused a ladder to be carefully and noiselessly placed against the wall, and, mounting it rapidly, with the agility of spiders climbing up their web, presently found themselves on the top. The sound of the clappers now became more distinct, and showed the approach of the sentinel; to elude whose notice they at once dropped to the ground on the inner side. But in vain; the man saw them drop, and uttered an exclamation. Before he could repeat it, however, they rushed upon him, and, throwing him down, bound his arms tightly. “You must guide us, and truly too,” they cried, gagging their prisoner as they spoke, and attaching him by a cord to the person of one of them. Seizing the fellow’s clappers, they then went the rounds, forcing him to show the way, and clapping, clapping, just as the sentinel himself might have done. Were they not a couple of stout-hearted blades?

Presently the sound of a whistle is heard. Yazama and his companion know that the moment for action is come.

Clapping loudly, they shout “Ama,” “Kawa,” and, drawing back the bolts, throw wide open the great gate, through which Rikiya is the first to rush, followed closely by Sugino, Kimura, and his brother.

“Here we are, here we are,” cry the men of the party, as they crowd tumultuously in.

Rikiya, meanwhile, scans closely the line of outer shutters, without being able to alight upon a weak spot. Remembering, however, his father’s device, suggested by the snow-laden bamboo, he deems the occasion a fit one for putting it into execution, and, ordering the unsplit bamboos they had brought with them to be strung with stout cord, causes the ends to be inserted in the upper and lower grooves in which the shutters move.

“Once, twice, thrice,” and all the strings are cut at the same moment; the bamboos straighten themselves suddenly, and all at the same time, so prizing out the upper framework and pressing down the lower crosspiece that the row of shutters fall in with a simultaneous clatter.

“Now for the attack,” shout the leaders, while cries of “Ama,” “Kawa,” fill the air. The retainers of the house, aroused by the uproar, begin to show themselves, carrying torches and lanterns. The rear attacking party, having made their way through the rear gate, now appear, one company headed by Goyemon, the other by Yuranosuke. The Karô, seating himself upon a camp-stool, gave his orders. His followers, few in number as they were, fought with desperate courage, and displayed to the utmost their skill as swordsmen.

“Have no eyes for aught but Moronaho,” cried Yuranosuke, “’tis his head that we require.”

Aided by Goyemon, the Karô directed the struggle on every side, while the young men, vieing with each other in bravery, kept up a constant clashing of weapons.

To the north of the mansion of Moronaho lay that of Nikki Harima-no-kami;[8] to the south, the residence of Ishido Umanojô.[9] On either side, the roofs of the buildings were crowded with men carrying lanterns, twinkling in the darkness of the night like the stars in heaven.

“Ya, ya,” they cried, “what means all this uproar and confusion, clashing of weapons, and hurtling of arrows? Are you attacked by rioters, or by robbers, or has a fire broken out somewhere? We have been commanded to find out what is going on, and inform our masters of the cause of the disturbance.”

“We are liegemen of Yenya Hanguwan,” replied Yuranosuke, without a moment’s hesitation. “Some forty of us banded together to revenge our lord’s death upon his enemy, and are now struggling to get at him. I who address you am Ohoboshi Yuranosuke, and my companion here is Hara Goyemon. We are not rising against the government, still less have we any quarrel with your lords. As to fire, strict orders have been given to be careful, and we beg you not to be under any apprehensions on that score. We only ask you to leave us alone, and not to interfere with us; if, as neighbours, you should think yourselves bound to assist our enemy, we shall be obliged, despite our inclination, to turn our weapons against you.”

To these bold words of Yuranosuke the retainers of the noblemen on either side of the mansion of Moronaho shouted back approvingly:

“Right well done, right well done; in your place we should feel ourselves bound to act as you are acting; pray command our services.”

And the next moment the roofs were deserted, amid cries of “Down with your lanterns, there, down with your lanterns.”

Meanwhile the struggle with the retainers of Moronaho continued, some two or three only of Yuranosuke’s comrades being wounded after an hour’s fighting, while quite a number of the enemy were stricken down.

Nothing, however, could be seen of Moronaho, although the soldier Heiyemon ransacked the buildings in search of him.

“I have searched every room,” cried Heiyemon, approaching his chief, “and probed the ceilings and floors with my spear, but without coming upon any trace of our enemy. But I looked into his sleeping-room, and found the bed-clothes still warm, so that, seeing what a cold night it is, he cannot have got far away. Possibly he has made for the great gate, so, without further delay”

The soldier was on the point of hastening away to guard the issue he had referred to, when he was interrupted by a voice crying:

“Ho, there, Heiyemon, not so fast, not so fast.”

The next moment, Yazama abruptly made his appearance, dragging with him their long-sought enemy, Moronaho.

“Look at him, look at him,” cried the elated captor, “I found him hidden in an outhouse, and dragged him here alive.”

The sight of their enemy in their power revived the cast-down spirits of the conspirators, as the dew revives the drooping flower.

“Well done, well done, indeed,” cried Yuranosuke. “But he must not be put an end to unceremoniously. He was a Shitsuji[10] in the Empire for a time, and must be put to death in due form.”

At a sign from Yuranosuke, Moronaho was placed in a prominent position in an adjoining apartment.[11]

Yuranosuke, addressing the victim, exclaimed: “Though but as doubly humble retainers[12], we have ventured to force ourselves within your walls, impelled by the desire of avenging the death of our lord upon his enemy. We pray you pardon our violence, and beg of you that you will present us with your head,[13] according to the usage of our country.”

Moronaho, though a vile sort of creature enough, yet managed to keep a composed countenance, exclaiming with forced calmness:

“Right, right, I am ready; here is my head—take it.”

Thrown off his guard for a moment, the Karô approached his prisoner, who, suddenly drawing his sword, aimed a blow at Yuranosuke, which the latter only escaped by a nimble leap aside, and twisting up his assailant’s arm.

“Ha,” cried the Karô, “a clever stroke that. Sah! Friends, upon him—you may slake your thirst for vengeance now.”

Another moment, and the body of Moronaho lay on the floor, covered with wounds.

The conspirators crowded round it, wild with excitement, shouting:

O rare sight! O happy fortune! Happy are we as the môki[14] when he found his waif, fortunate as though we gazed upon the flower of the udonge,[15] that blossoms but once in three thousand years.”

Cutting off their enemy’s head with the dagger with which their dead master had committed seppuku, they resumed their orgy, exclaiming:

“We deserted our wives, we abandoned our children, we left our aged folk uncared for, all to obtain this one head. How auspicious a day is this!”

They struck at the head in their frenzy, gnashed at it, shed tears over it; their grief and fury, poor wretches, beggared description.

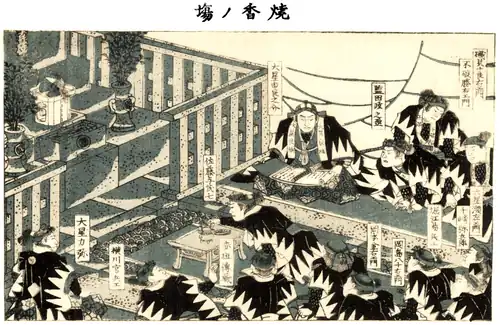

Yuranosuke, drawing from his bosom the ihai[16] of his dead master, placed it reverently on a small stand at the upper end of the room, and then set the head of Moronaho, cleansed from blood, on another opposite to it. He next took a perfume from within his helmet, and burnt it before the tablet of his lord, prostrating himself and withdrawing slowly, while he bowed his head reverently three times, and then again thrice three times.

“O thou soul of my liege lord, with awe doth thy vassal approach thy mighty presence, who art now like unto him that was born of the lotus-flower to attain a glory and eminence beyond the understanding of men! Before the sacred tablet tremblingly set I the head of thine enemy, severed from his corpse by the sword thou deignedst to bestow upon thy servant in the hour of thy last agony. O thou that art now resting amid the shadows of the tall grass,[17] look with favour on my offering.” Bursting into tears, the Karô of Yenya thus adored the memory of his lord.

“And now, comrades,” he resumed, after a pause, “advance each

Retribution.

of you, one after the other, and burn incense before the tablet of your master.”

“We would all,” cried Ishido, “venture to ask our chief first among us to render that honour to our lord’s memory.”

“Nay,” answered the Karô, “’tis not I who of right should be the first. Yazama Jiutarô, to you of right falls that honour.”

“Not so,” cried Yazama, “I claim no such favour. Others might think I had no right to it, and troubles might thus arise.”

“No one will think that,” exclaimed Yuranosuke. “We have all freely ventured our lives in the struggle to seize Moronaho, but to you,—to you fell the glory of finding him, and it was you who dragged him here, alive, into our presence. ’Twas a good deed, Yazama, acceptable to the spirit of our master; each of us would fain have been the doer of it. Comrades, say I not well?”

Ishido assented on behalf of the rest.

“Delay not, Yazama,” resumed Yuranosuke, “for time flies fast.”

“If it must be so,” cried Yazama, as he passed forward, uttering gomen[18] in a low tone, and offered incense the first of the company.

“And next our chief,” exclaimed Ishido.

“Nay,” said the Karô, “there is yet one who should pass before me.”

“What man can that be?” asked Ishido, wonderingly, while his comrades echoed his words.

The Karô, without replying, drew a purse made of striped stuff from his bosom. “He who shall precede me,” cried the Karô, “is Hayano Kampei. A negligence of his duty as a vassal prevented him from being received into our number, but, eager to take at least a part in the erection of a monument to his liege lord, he sold away his wife, and thus became able to furnish his share toward the expense. Thinking that he had murdered his father-in-law to obtain the money, I caused it to be returned to him, and, mad with despair, he committed seppuku and died—a most miserable and piteous death. All my life I shall never cease to regret having caused the money to be returned to him; never for a moment will be absent from my memory that through my fault he came to so piteous an end. During this night’s struggle, the purse has been among us, borne by Heiyemon—let the latter pass forward, and in the name of his sister’s dead husband, burn incense before the tablet of our lord.”

Heiyemon, thus addressed, passed forward, exclaiming:

“From amidst the shadows of the tall grass blades the soul of Kampei thanks you for the unlooked-for favour you confer upon him.” Laying the purse upon the censer, he added:

“’Tis Hayano Kampei who, second in turn, offers incense before the tablet of his liege lord.”

The remainder followed, offering up in like manner, amid loud cries of grief, and with sobs and tears, and trembling in the anguish of their minds, incense before the tablet of their master.

Suddenly the air is filled with the din of the trampling of men, with the clatter of hoofs, and with the noise of war-drums.

Yuranosuke does not change a feature.

“’Tis the retainers of Moronaho who are coming down upon us—why should we fight with them?”

The Karô is about to give the signal to his comrades to accomplish the final act of their devotion by committing seppuku in memory of their lord, when Momonoi Wakasanosuke appears upon the scene, disordered with the haste he had used, in his fear of being too late.

“Moroyasu, the young brother of Moronaho, is already at the great gate,” cries Momonoi. “If you commit seppuku at such a moment it will be said that you were driven to it by fear, and an infamous memory will attach to your deed. I counsel you to depart hence without delay, and betake yourselves to the burial-place of your lord, the temple of Kômyô.”

“So shall it be,” answered Yuranosuke, after a pause. “We will do as you counsel us, and will accomplish our last hour before the tomb of our ill-fated lord. We would ask you, Sir Wakasanosuke, to prevent our enemies from following us.”

Before the Tomb of Yenya: The Last Homage of the Clansmen.

Hardly had Yuranosuke concluded, when Yakushiji Jirôzayemon[19] and Bannai Sagisaka suddenly rushed forth from their hiding-places, shouting:

“Ohoboshi, villain, thou shalt not escape,” and struck right and left at the Karô. Without a moment’s delay, Rikiya hastened to his father’s assistance, and forced the wretches to turn their weapons against himself. The struggle did not last long. Avoiding a blow aimed at him by Yakushiji, Rikiya cut the fellow down, and left him writhing in mortal agony upon the ground. Bannai met with a similar fate. A frightful gash upon the leg brought him to his knee,—a pitiable spectacle enough,—and a few moments afterwards the wretch breathed his last.

“A valiant deed, a valiant deed!” ******* ******* For ever and ever shall the memory endure of these faithful clansmen, and in the earnest hope that the story of their loyalty—full bloom of the bamboo leaf[20]—may remain a bright example as long as the dynasty of our rulers shall last, has the foregoing tale of their heroism been writ down.

End of the Eleventh Book.

- ↑ The tale is as follows. In the reign of the Chinese emperor Riuko, Chôryô filled the post of Commander-in-chief. One day, passing over a bridge known as the Bridge of Hi, he met an old man on horseback, who dropped his sandal and somewhat surlily told Chôryô to pick it up for him. Though annoyed at the tone in which the request was made, the great man, seeing the age of his interlocutor, complied with it. Thereupon the old fellow told him to be at the bridge at dawn on the fifth day from that, and he would meet with due reward. Chôryô accordingly presented himself on the bridge on the fifth day, but was reproached by the old man as being late, and told to come again at the end of another five days—which he did, and was again dismissed in a similar manner and for a similar reason. The third time, Chôryô took care to be at the bridge by midnight, and this time was well received by the old man, who bestowed upon him a book treating of the art of war, the Rikuto Sanriyaku (previously mentioned in the Ninth Book), and, telling him that he would meet him once more that day seven years, suddenly disappeared. Chôryô visited the bridge in the seventh year, but found nothing there but a huge yellow-coloured stone, and thus came to know that his mysterious aquaintance was a spirit sent to try his patience and good manners. The name Sekikô is an abbreviation of Kôsekikô (“the lord of the yellow-stone”), the appellation by which the seeming old man was afterwards known.

- ↑ Near Kamakura.

- ↑ There is here a pun in the original which is not capable of being rendered in the translation. The whole meaning of the passage is, however, given.

- ↑ In the text followed, the forty-six letters of the Japanese syllabary are here enumerated in their usual order, with the names of the adventurers interspersed in such a manner as to allow of a thread of meaning connecting the whole passage.

- ↑ There again occurs one of those jeux de mots which the Japanese apparently mistake for wit. There are, however, equally poor ones, both in conception and application, to be found in Aristophanes, and even in the mouths of Homer’s goddesses, as in the speech of Athênê, Od. A. 62: “* * * ὁι τοσον οδυσαυ Ζευ.” The last letters of the Iroha or Japanese syllabary may be read as forming a phrase meaning “not to be overcome by drink.”

- ↑ There are forty-six letters in the Japanese syllabary, excluding the final nasal sound.

- ↑ One of the commissioners officially present at the seppuku of Yenya, described in the Fourth Book, who signalised himself by the brutality with which he executed his duty.

- ↑ I.e., Nikki, Lord or Count of Harima.

- ↑ One of the commissioners mentioned in the Fourth Book.

- ↑ Regent or Viceroy under the Shôgun.

- ↑ Such seems to be the meaning of the author, who is here more than usually obscure.

- ↑ Lit., “retainers of a retainer.”

- ↑ The Karô wished his enemy to commit seppuku, and then to take his head. This was the form of vengence that most approved itself to the sentiments of a Japanese gentleman of the old school.

- ↑ The môki, according to a Chinese fable, was a species of sea-tortoise with one eye in its belly. For three thousand years the monster had longed to see the light, but in vain. One day, while swimming about the surface of the sea, it came into contact with a piece of drift-wood, to which it immediately clung in such a manner that the belly was uppermost under the wood, a ragged hole in which fortunately allowed the tortoise the opportunity of at last satisfying its long-cherished desire.

- ↑ The udonge is a plant so rarely seen in flower that it is fancifully said to bloom but once in three thousand years.—Vide Appendix.

- ↑ Vide Appendix.

- ↑ An euphemism for the grave: a Buddhic term.

- ↑ I.e., “with your august permission.”

- ↑ One of the commissioners referred to in the Fourth Book.

- ↑ Take (bamboo) formed part of the boy-name of each successive occupant of the throne of the Shôguns during the period in which the so-called temporal power was vested in the hands of members of the Tokugawa dynasty.