Wise Parenthood (15th edition)/Chapter 4

TO be entirely satisfactory a method should combine at least three essentials—safety, entire harmlessness, and the minimum disturbance of spontaneity in the sex act (that is to say, it should be as little inæsthetic as is possible).

Marriage is too often the grave of romance, and undoubtedly the disabilities of recurrent pregnancies, and the consequent necessity which married people have so long felt of using some means of prevention, have done much to deaden the beauty and undermine the security of the marriage relation. Alas! that it should be so, but without question many of the less worthy people have known better how to retain the adventitious charms of union than have those united in holy wedlock.

Ideally all knowledge of methods of controlling conception should be confined to the married and those immediately about to marry. Something approaching a sacred initiation into the rites of marriage should be available, under dignified and impressive circumstances, for every wedded pair, but alas! this is a remote ideal, and to-day far too often the married are in ignorance of what should most vitally concern them.

This book is written essentially for the married. It is true that it may pass, directly or indirectly, into the hands of those who have not put any religious or civil seal on the bond of their love. But if it does, one can be sure that it will reduce, and not increase, the racial dangers which are so often coincident with illicit love. Moreover, as I have often said on the public platform when questioned about the dangers of spreading immorality, the methods which I advise and those disseminated by the Clinic and the Society for Constructive Birth Control cannot be used by a virgin girl. While on the other hand, if the knowledge in this book may enable a few wives apparently without reason to avoid all childbearing, it is surely well that such women should not be mothers, for motherhood is too sacred an office to be held unwillingly.

Some people, generally those who have been brought up in the hazy ignorance of either an idealistic or a shamefaced attitude towards sex, refuse to use any preventive method. Not infrequently a woman who has had several children and acquired a fear of pregnancy so refuses, and cuts off her husband from all normal intercourse, with, possibly, serious effects on the health of both. Such people should try to realise that because there may be a few inartistic moments in a course of procedure, that cannot rationally be held to prohibit the procedure. It would be as reasonable to decide that as some of the processes of cooking and the after-effects of digestion are inartistic, solid food should not be taken. In this physical world we are to a considerable extent dependent on the physical facts of our bodies, which we cannot override without making grievous trouble either for ourselves or those around us.

No method is absolutely safe, but if two methods, each very nearly reliable, are combined, then something approaching absolute safety is achieved. It must be remembered, however, that the most perfect procedure devisable cannot be safe in the hands of one who is careless. The one to whom the consequences of carelessness are most serious is, of course, the woman; she, therefore, is the one who should exercise the precaution. Consequently she must have knowledge sufficient to be sure that she is taking the right steps. A large number of women are not acquainted with the physical structure of the human body; it is, therefore, necessary to describe a few essential features which all women must understand in order to take the best precautions.

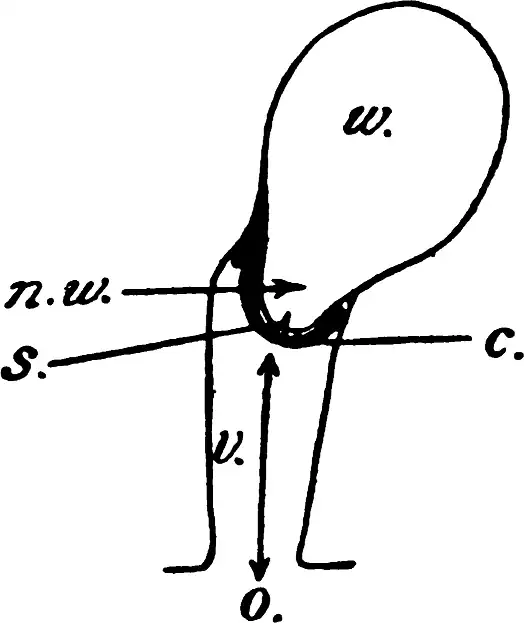

A married woman has no difficulty in distinguishing the entrance of the vagina. The vagina itself is not a sex organ, but is the canal leading to the important internal organ—the womb. The ovaries, the actual source of the egg cells, are entirely internal and do not concern

us here. The womb, however, though it is internal, can readily be felt near the end of the vaginal canal (v in diagram) if the woman feels for it with her longest finger (of which the nail should be very clean, and is best covered with boracic vaseline before it is gently inserted). The distance from the opening of the vaginal orifice (o), which is the external opening, to the end of the vaginal canal where the womb can be just felt by most women, is generally about the length of the woman's own finger, although some women are made with long vaginal canals and short fingers; just as some have long noses and short chins. Such women may find it difficult to use this particular method; they are relatively few in number however. The womb (w) lies internally, but at the end of the canal and a little to one side, its neck projects like an inverted dome of soft firm tissue (n w); in the centre of this is the very small actual opening (s) through which the sperm will pass if it is to fertilise an egg cell. This opening, however, is very small, and would not be felt under normal circumstances by most women. I have myself observed, and have confirmatory evidence from others, that there are times when this neck is wide enough open to receive the actual tip of the male organ. At such times, of course, conception is particularly likely to take place.

The woman should know that this opening is there, and that, therefore, if she wishes to prevent the sperm reaching the ovum this small entrance is the critical gateway through which the sperm must not be permitted to pass. In the vagina itself the sperms are merely waiting in the ante-room. The vagina, however, is of great importance to the man in the sex act, for it is into the vagina that his organ enters, and there it receives the sensations necessary for the completion of the normal act, the contact of the soft tissues of the parts being an important element in the right performance of the vital function. The ideal preventive method, therefore, does not interpose anything between the tissues of the vaginal canal and the male organ, but it should close the minute entrance of the womb and shut away the sperm from entering that critical part.

The best appliance at present available for doing this is a small rubber cap, made on a firm rubber ring, which is accurately fixed round the dome-like end of the womb. It adheres by suction assisted by the resilience of the firm rim against the circular muscle's and remains securely in place, whatever movement the woman may make. They do not grip or pinch the neck of the womb, as is often implied by ignorant critics of the method. (In the diagram, c shows the rubber cap in position.) These small rubber caps are quite simple, strong, easily fitted, and should be procurable from any first-class chemist.[1] The important point about adjusting them is that they should be of the right size. The average woman is fitted by a small or a medium size, but the woman who has had several children generally wants them larger. Educated and intelligent women can generally fit themselves quite easily, but some women cannot, and for them personal instruction is necessary.

Women who are quite healthy, and under the impression that they are entirely normal, may perhaps find the use of this cap impossible, or find that if they do use it, it fails them, because, without knowing it, they may have experienced some internal after-effects of childbirth. One of the commonest (which is of frequent occurrence among those women who have been to the Clinic) is the laceration of the neck of the womb as a result of the stretching by the child's head at birth. The result is that, although the neck of the womb has healed, and the woman is quite unconscious of any pain or disability, instead of a circular contracting muscle, the neck consists of two or more flaps, one of which may get on the outside of the rim of the cap or otherwise interfere with its proper placing, and in any case make it difficult or unreliable for the woman to place it in position herself. Hence, unless a woman is acquainted with anatomy and knows herself to be normal, it is much better that she should be examined by an expert, such as the nurse at our Clinic or one of the doctors in touch with our Clinic, before using the cap herself. After one examination, a healthy woman need have no further expert assistance until she has another child, when she should be examined again after child-birth.

For women who are doubtful about their own perfect normality, or where injury has occurred during child-birth, the simpler method advised on page 52 should meanwhile be used.

Before insertion the rubber cap should be moistened with very soapy water, so as to allow it to slip in easily. Quinine ointment is sometimes preferred for this purpose, and if both the inside and outside of the cap be well covered with it, it may be unnecessary to insert quinine pessary later (see page 41) if the cap is very well fitted. It should be placed in its position for use at any convenient time, preferably when dressing in the evening and some hours before going to bed. The great advantage of this cap is that once it is in and firmly and properly fitted it can be entirely forgotten, and neither the man nor the woman can detect its presence. This point, although primarily an aesthetic and emotional one, is of supreme physiological benefit also, and is one of the strongest arguments for this method. The cap should be put in at least some hours before bedtime, and left in undisturbed until at least the following day; but I very much advise it being left in two or three days after any individual act of union. The reason for this will be mentioned below. After use, even if the cap is to be again inserted in an hour or two, it should be carefully washed in soapy water, and though not essential where there is perfect health, it is much better to dip it into a weak solution of some wholesome disinfectant before putting it away in the jar of water recommended in the Appendix. Some women, as advised by the medical man who invented caps, insert the cap when the monthly period has entirely ceased, and leave it in for three weeks, but I have never recommended this and consider it inadvisable. This is safe only with perfect health, and few of our modern women can boast that. The cap should not be worn needlessly there is no reason to do so, as it can be slipped in easily when desired. If a woman suffers even trifling ill-health, accompanied by a slight local discharge, then there is no doubt that the cap should never be left in more than a couple of days at a time, though after being taken out for an hour or two and cleansed, it may be re-inserted on the same day. A woman who needs to use her cap very frequently would do well to have two and to keep them alternately in a disinfectant solution. Women very greatly vary in their vaginal effect on rubber. When it is unlikely that it will be required, it is always better not to keep the cap in place but to remove it.

Now the cap alone, if it really fits and if it is left in for two days so that the sperm are naturally got rid of without having a chance to enter, should be completely safe by itself. There is, however, always the possibility of a slight displacement or of a particularly active sperm remaining after the cap has been taken out and then using the opportunity to swim into the entrance of the womb. To render this impossible, or at any rate unlikely in the extreme, it is as well to plasmolise the sperms when they first come in; and in order to do this the best method is to have some plasmolising substance in the vagina at the time when the sperms are deposited. The reason why it is better to do this rather than to wait and deal with the sperms afterwards is given in the paragraph on douching (see page 66).

Several substances may be used for the purpose of plasmolising the sperms. One which is very easy, and widely used because it is specially prepared and can be purchased readily, is the soluble quinine pessary. This is a mixture of various quinine compounds with cocoa-butter for its greasy base. In my opinion the grease affords valuable protection, and the same quinine compounds mixed with gelatine or other non-greasy substances (sometimes sold to those who object to grease) are not as reliable. Experience at the Clinic, however, has confirmed what I knew from personal experience many years ago, namely, that quinine is partly absorbed by the vaginal walls and does not entirely suit all women. We have had prepared for use at the Clinic (and have there tested them) greasy suppositories made entirely without quinine, and with chinosol in its place. Chinosol is a harmless and very satisfactory disinfectant, specially recommended by Sir Arbuthnot Lane for its valuable properties. Hence, for a double reason, the chinosol greasy pessary is to be preferred to the quinine, for while the quinine pessary is satisfactory to about 95 per cent. of women, the chinosol pessary is completely satisfactory, and the chinosol has a subsidiary useful property. Since it has been perfected, it has been the only form of greasy pessary recommended at the Clinic. Like the greasy quinine pessary, it can be slipped in at the last few moments, so that the crisis is not æsthetically interfered with.

In a few words, therefore, I advise as the safest and readiest method of contraception for the perfectly normal woman, that she should use the all-rubber cap fitted in some time before retiring, and slip the chinosol greasy pessary in a few minutes before the act. With these precautions, nothing further need be done. There is no getting up to douche or to take other precautions in the middle of the night. It is not even necessary to remove the cap or to take any steps the following morning. The usual processes of Nature will dispose of the now impotent sperms. Those who are very anxious, however, who may feel this calm inactivity insufficient, may desire to douche the next morning and take out the cap. If they wish to do so, there is no harm in using one of the douches mentioned on page 71, so long as douching is not too frequently indulged in and does not become a regular habit.

The action of quinine on the vagina varies considerably with different types of women. For the average woman it is quite harmless, and indeed for some beneficial. More detail about this interesting point will be found in my larger text-book, "Contraception, Its Theory and Practice." On the other hand, I am convinced that it is, at least, partly absorbed by the walls of the vaginal canal, and thus penetrates the system in such a way as to make peculiarly sensitive women either somewhat sleepless or to interfere slightly with the digestion, or to initiate local tenderness. It has been proved by scientific experiment that some substances (iodine, for instance) do penetrate through the walls of the vagina and get into the circulatory system with remarkable rapidity. Whether or not the same applies to quinine has never been tested, so far as I am aware, except by the actual experience of those who have long used it as a contraceptive. I am satisfied that it does penetrate the system of some (and therefore presumably of all) women; thereupon it depends on the individual's general reactions whether it is beneficial or upsetting. Women who have for some time past used quinine pessaries have no need to feel doubtful about them or to stop their usage if they are entirely satisfied with them; but those beginning the use of contraceptives would be better advised to use chinosol greasy pessaries from the first.

One slight drawback to any soluble greasy pessary is that the cocoa-butter, of which they are made, has a smell to which some people object; but this is now almost universally overcome by the various makers who have placed on the market odourless or pleasantly scented cocoa-butter pessaries.

A slight disadvantage of the greasy pessary when made in the ordinary size is that it produces more lubrication than is necessary for some women, and the friction, essential for the complete orgasm, may be difficult to obtain. Such people should use the small-sized chinosol pessary which is now obtainable.

The only real drawback to a greasy pessary is that the melted cocoa-butter tends to spread on to linen. For those who object to this or find it inconvenient in any way, the following suggestions may be useful as alternatives:—

(a) A pad of cotton wool, thoroughly smeared with vaseline, which has been mixed with powdered borax, may be inserted into the end of the vagina. This may be used by those who find soap in any way unpleasant, or irritating, as it should tend to be more soothing.

(b) A strip of boracic lint may be inserted and packed round the cap after its insertion and not very long before union takes place. This is perhaps the cleanest and easiest of these alternatives.

None of these methods, however, seem to me so easy nor quite so satisfactory as the soluble greasy pessary.

Several varieties of soluble pessaries are made with other substances on the Continent, but they are not so easily obtained in this country, though some, particularly of German make, are being pushed. In France the peasant women make up such things for themselves, and a woman who has time and skill could do this, using gelatine instead of cocoa-butter. Gelatine, however, is not in itself an assistance, as is cocoa-butter, and so gelatine suppositories are less reliable than ones composed of a greasy substance. The grease itself clogs the sperms and prevents their movements.

The greatest care should be exercised in getting a rubber cap exactly to fit. In order to put it in, the woman should be in a stooping position, sitting on her heels with her knees completely bent, and she should press the rim of the cap together so as to slip it into the opening. When the cap reaches the end of the vaginal canal it will naturally expand and then tends to find its place itself (c in diagram). It wants pressing firmly round the protuberance of the womb, however, and if it is too small it may miss covering the critical opening. It should be the largest size which fits with comfort, and the rounded neck of the womb should be felt in the soft part of the cap. One too large, of course, will leave a gap and be more disastrous than one too small. A woman who is afraid of her own body or ignorant of her own physiology should get a practitioner to fit her with a rubber cap or attend the Birth Control Clinic; but for women of average intelligence this is not necessary. (It is shown in place in the diagram at c.) On the other hand, as the relative sizes of all the parts of our bodies vary very much, a woman may have a vaginal canal longer than her own centre finger, and would then have to be fitted by a medical practitioner, a nurse, or some competent person. In the first instance, she should purchase more than one size to find out exactly what suits her. On each occasion it should be pressed firmly, after some active movement, to see that it does not slip. When the cap is once firmly on, both the man and the woman can be at ease about it, as it should remain in a couple of days without dislodgment. But it should be tested by feeling round it before each time of union. It should perhaps be mentioned that it is quite impossible for the cap to enter farther or get into the body cavity and "lose itself" among the organs, as some ignorant people fear.

In order to get it out, all that is necessary is to bend a finger under its rim and jerk it off. The cap can then be brought out, washed and left to dry until it is next wanted. The little jerk at the edge of the rim itself is necessary to overcome the suction effect, which some women find unpleasant when they merely tug at the ribbon which is generally attached to the rim of the cap and lies along the vagina when the cap is in place. It is generally better to have a cap without any such attachment, or to cut off this ribbon and its attachment and rely solely on the finger to jerk off the cap. Rubber tends to rot; so, after some months' use, it should be carefully examined to see that it is not torn or become liable to be readily perforated. If the woman can afford it, I should recommend a new one every six months or so, though with great care they will last a couple of years.

A great many different forms of rubber cap are on the market, shaped in various ways, but the circular, strong ring, with the high dome-shaped soft centre, called the ProRace, is the kind I recommend and which to the average woman is by far the most satisfactory. The rim should be composed of firm and solid, but soft and flexible, rubber, and not contain any metal spring or wire. (See Appendix.)

This procedure on the part of the woman, though it may sound elaborate and a little sordid when described in full detail, is, nevertheless, after the first usage, so simple and so unobtrusive, that it can be entirely forgotten during the marriage rite itself. It therefore alone among mechanical preventive methods does not tend to destroy the sense of spontaneous and uninterrupted feeling, which is so vital an element in the perfected union, and at the same time allows all the benefit to be derived from it. Doubtless when once the intelligent inquiry and scientific research commensurate with the importance of the subject are devoted to it, better preventive methods may be devised, although there seems little immediate prospect of any more satisfactory new method meeting all the requirements. In the meantime this combination of methods is far the best course which is available at present, and, indeed, the only one which I can sincerely recommend, and it has the endorsement of the leading medical practitioners.

| • | • | • | • | • |

A medical practitioner opposed to contraception has announced that he has known women who cannot wear the cap I describe, quoting one lady doctor even as being unable to insert the cap for herself: from this he implied that the cap must therefore be useless! His argument was absurd, for he was quoting cases which are abnormal in a scientific sense, and applying the result to the normal. I think I know personally the lady doctor to whom he refers; but at any rate I know a lady doctor who consulted me and told me she could not fix the cap as she has a very long vagina and small hands. In quite early editions of this book I noted such exceptions (and others) who would be unable to wear the cap. The opponent who uses them in argument against the method for normal women is only arguing illogically and should not be allowed to influence reasonable opinion.

| • | • | • | • | • |

Another medical practitioner, in favour of contraception, Mr. Norman Haire, M.B., has recently (July, 1922, in the Malthusian League's practical leaflet) advocated the Dutch or hemispherical type of cap in preference to the small occlusive I describe above. I welcome the fact that the other Society should now adopt my main thesis, namely that an internal rubber cap worn by the woman is the best form of contraception. Whether one shape of cap or another is worn is a point of minor difference, as the fundamental principle is the same in the use of all the various internal rubber caps, though they vary greatly in details. Most unfortunately Mr. Haire ardently advocates the Dutch simple half-sphere pessary in preference to the small occlusive cap worn on the neck of the womb. I wish therefore to point out serious objections to the Dutch cap which its masculine advocates entirely overlook.[2] Since stating these objections in the Lancet further serious drawbacks to this type of cap have come to my notice.

The Dutch cap must be worn so as to cover the whole end of the vagina, and it is therefore necessary for a woman to wear a cap with a very much larger diameter than would be the diameter of the occlusive pessary, for the Dutch cap depends on a certain stretching of the end of the vaginal walls for its power to remain in position. Hence the user of the Dutch cap has the end of the vagina stretched, and moreover the end of the vagina is stretched in such a way that certain movements of physiological value which ideally the woman should make are then impossible. It is true that few women either know or practise the completest physiological and natural union; but, in my opinion, that is no reason for justifying the advocacy of a means of contraception which inherently makes certain natural and valuable movements impossible.

A further objection to the Dutch cap is that, of necessity, it must cover the whole end of the vagina, and that therefore the tissues immediately round the neck of the womb are deprived of contact with the seminal fluid. There is reason to believe that these tissues are among the most sensitive as well as most absorptive of the woman; they are not covered or interfered with by the small occlusive cap with narrow rim which I advise, but they are completely covered by the Dutch cap, and it is not good that they should be covered.

I am therefore opposed to the use of the Dutch or Malthusian cap advocated by Mr. Haire for general use.

At my Clinic we have advised the Dutch cap now and then for abnormal or difficult cases, when it sometimes proves very useful. Cases, for instance, when the woman has become excessively fat and the internal organs are stretched or out of place, and she is therefore incapable of the ideal and perfect movement anyway, and finds it difficult or impossible to adjust the small cap; also cases when the neck of the womb is injured, and some others.

But throughout all my work on behalf of our sex-life, I only advocate procedure for the normal and healthy, in the hope that they may improve and make more perfect their own lives. I recognise as useful palliatives or as necessary treatment a great variety of measures suitable for the great variety of diseased, injured and abnormal persons now among us; but I deplore the tendency still rampant to set our general standards by such persons. The advocacy of the Dutch cap for general use by a medical practitioner is only one more regrettable illustration of the all-too-frequent fact that the medical profession (consisting of those who treat disease) is frequently blind to the requirements, to the existence even, of perfect and joyous health.

As mentioned on page 38, some women have a lacerated cervix without in any other way suffering in their health, and some have slight prolapse or other defect sufficient to make the fitting of a cap difficult or unreliable. Some find the actual fixing of the cap beyond their unaided powers. For these and other reasons the cap is not always suitable for use by those who cannot have expert personal advice, and for a long time past I have recommended to women unable immediately to get the necessary examination and help that they should meanwhile utilise the recent modification of an old-fashioned method which we are finding satisfactory at the Clinic. This is the original "sponge method," first publicly made known in this country in 1823, and now generally superseded by more elaborate and expensive things. We find, particularly in homes where life is simple and the desire is to spend little money, that the simplest, safest and easiest method for uninstructed women to use is to soak in olive oil a fine-grained sponge (rounded to about the size of a small orange, and selected with care so that no large holes penetrate it). It should be soaked well in olive oil (or ordinary salad oil), and the oil nearly all squeezed out before the sponge is inserted. Some prefer olive oil with chinosol dissolved in it.

Some years ago, when this book was first written, a large proportion of the women of the country who were healthy and normal turned to it for contraceptive information; now the greater number of normal and intelligent women are satisfied and have got information which they are using; but what may be described as the "difficult cases" are still trying one type of contraceptive after another, seeking one to suit them. The increasing proportion of difficult cases coming to the Clinic[3] shows that the study of contraceptives must reach a stage when the injured, abnormal or difficult case must be specially considered. Meanwhile I recommend the use of the sponge soaked in oil as most likely to succeed with slightly injured or somewhat difficult cases, for, although the cap is simplicity itself to adjust when used by a normal woman, it is not entirely suitable for the abnormal or injured, or those very ignorant and inexperienced.

I should like to emphasise the very important fact that contraception for normal women is the simplest possible hygienic measure; but contraception for the injured or abnormal, even in a slight degree, may be a complicated and difficult medical problem.

| • | • | • | • | • |

The most difficult cases of all, and at the same time those most urgently needing to exert reliable control over conception, are the women who are harried, overworked and worried into a dull and careless apathy. These too often will not, or cannot, take the care and trouble to adjust ordinary methods of control so as to secure themselves from undesirable conceptions. Yet they do not desire more children, and often have already produced a number of low-grade or semi-feeble-minded puny infants.

All health workers, district nurses, and workers in schools for mothers know scores of such women, and many have appealed to me asking what they are to advise for women too careless to use any ordinary method and yet who continue to give birth to hopelessly inferior infants which are only an expense and drag upon the community.

For such, in some of the former editions of this book, I suggested a method which leading American medicals have used with advantage, but I have found that the technique which is required is not yet sufficiently familiar to practitioners in this country to make it readily available. I trust the interest now taken in the matter may lead to a speedy recognition of the value of the lead given us in this direction by practitioners of other countries.

It seems easy enough to supply the intelligent and careful woman with physiological help; and for the careless, stupid or feeble-minded who persist in producing infants of no value to the State and often only a charge upon it, the right course seems to be sterilisation.

Curiously enough, in this country sterilisation is considered more mysterious and more feared than in America, where a number of States have compulsory sterilisation laws, and where thousands of sterilisations have been carried out successfully.

It ought to be known in this country that there is at present no quite simple and satisfactory method of sterilising women. Hence just the type of woman who most certainly should be sterilised in the interests of the State and of herself, namely, one with a slightly subnormal mentality or liable to epileptic fits, drink, etc., cannot be successfully sterilised without a major operation, so that she must use most carefully birth control methods or refrain entirely from married life.

But for men, sterilisation is comparatively easy—so trifling an operation that it is described by a leading American medical man "an office operation" when it is performed by simple vasectomy (see Birth Control News, June, 1923, Vol. II, No. 2). Of course, this is well known to medical practitioners, many of whom would be quite willing to perform the operation on their patients for moderate fees if they were requested to do so, but they shrink from suggesting it. It is for the public to take the matter into their own hands and ask for sterilisation for themselves or their children where it should be done. For instance, boys should be sterilised in families where there is epilepsy, or any degree of feeble-mindedness, not only in the parents but in the collaterals such as uncles or aunts, for feeble-mindedness and epilepsy are apt to "miss a generation," and appear in a manner unexpected to the parents, although the likelihood of the calamity arising is obvious to scientists who know some of the laws which govern these deplorable racial defects. Now that birth control is becoming so well established, it is time that the idea of sterilisation should be familiarised, so that those who would benefit by its application to themselves or their own families should be free without fear or anxiety to utilise it. The public will be ready to utilise it for racial purposes when its urgent need is realised. Not long ago a letter in The Times signed by some distinguished medical men advocated sterilisation in this country.

There are great varieties of individual needs on the part of various people, and as a good many other methods are in common use a few words about them are necessary, as I find that many people are using them without realising that they may thereby, to a greater or less degree, injure themselves.

- ↑ This round rubber cap is called the small check pessary or small occlusive pessary; sometimes, incorrectly, the small mensinga. I am not here speaking of the larger mensinga or matrisalus pessaries. A great variety of names are given to various types of the small occlusive pessary; the best make seems to me to be the ProRace. Forms with air-rims are often advised, but experience at the Clinic is against them. (See Appendix, pp. 79–81.)

- ↑ See also my letter in the Lancet September 9, 1922, p. 588.

- ↑ See "The First Five Thousand," by Dr. Marie Stopes. Published by Bale, Sons and Danielsson, Ltd., London.