Translation:Le Japon

Paris illustré

A. Lahure, Editor

13, Rue Jean-Bart, Paris

Charles Gillot, Director

L. Baschet, Editor

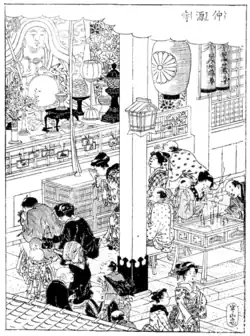

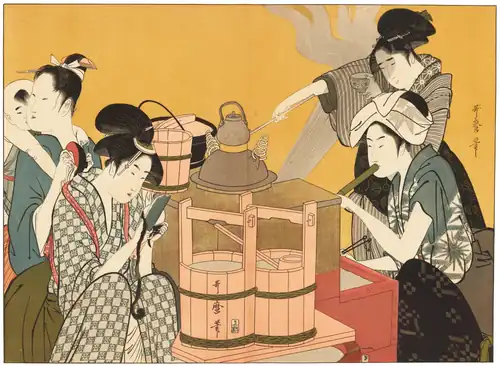

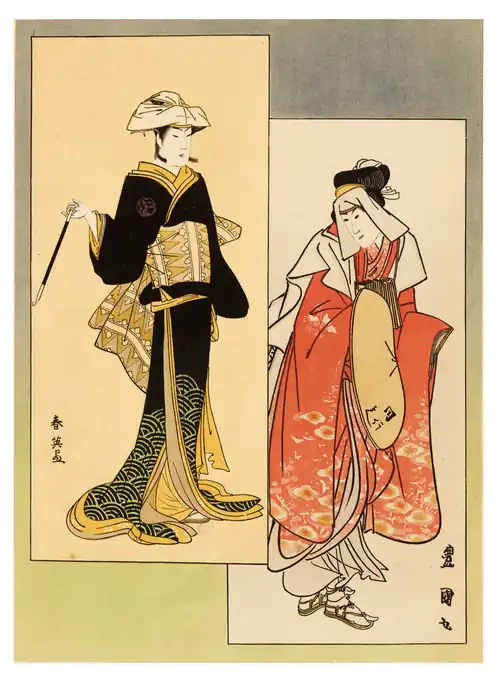

Utamaro.—A Singer of Dramas in a Meeting Hall.

Japan

Nowadays, with so many works on Japan existing in France, it is certainly pointless to make a new description.

However, Paris Illustré wants to make a short work to submit it to the public, as very complete works attempt this mediocrely. It also believes that this work, written by a Japanese, will have more local color.

Their idea is good; but why did they charge me with this mission, which should have been given to a Philippe Burty? I am not a scholar, but a dealer in art objects, in which I am an expert.

Before attempting to fulfil my mission, I would ask my readers for the greatest indulgence.

Japan’s new relations with the West have brought about a great change in our customs, so it would be incommodious to discuss those of our days. What I am to describe here is the Japan prior to the introduction of the new civilization.

History

Our history is divided into two periods: the mythological period and the historical period.

The historical period commences in the year 660 (before the Christian era) by the advent of Emperor Jimmu.

From Jimmu to the present day, one and the same family reigns the Rising Sun.

There have been 123 sovereigns in the space of 25 centuries and a half. During this time, the mores and customs have changed visibly and categorically.

Thus we may divide the historical period into three epochs:

- The epoch of primitive civilization;

- The epoch of Korean and Chinese civilication;

- The epoch of Europe making us a new god.

The second epoch, from the third century to the middle of the nineteenth, is that which best shows the Japanese character.

The introduction of Buddhism and the philosophy of Confucius, from the fifth through the ninth centuries, caused a great change in our habits. An immense progress was made in the entire empire. Temples were constructed, silk was woven, and our existence, simple until then, became replete with new luxuries.

Legislation took a Chinese form and the religion of Buddha established itself in our country.

At the court of the Mikado, etiquette became more and more rigorous and at Buddhist temples ceremonies became progressively more pompous.

In the ninth century it all attained to a complete development.

Poetry, painting, sculpture, architecture shone in all their brilliance. And since that epoch nothing has approached it. We can say that during the eleven centuries which followed, the preponderating influence of the Mikado’s court established at Nara dominated in all things.

From the point of view of political history this period presents us two faces:

The imperial government and the shōgunal government.

Under the imperial government all power belonged the emperor, while under the shōgunal government, the executive power was confided in the Shōgun, the general of the armies.

The constitution created in 1186 by the Shōgun Yoritomo, who established the fundamental bases of hereditary succession, but this power was the object of ambition for great men, and owing to the weakness of his heirs, other dynasties came to power one after another.

The last dynasty was of the Tokugawa family, which came to power in 1603 and rendered to the emperor in 1868.

The government of the Tokugawa having completed the civilization which we have to-day, it suffices to expose to our readers the former customs to give an idea of Japan of to-day.

The Land and the Climate.

The archipelago of Japan is composed, as everyone knows, of four main islands and about 4,000 smaller ones spread out from South to North of a generally temperate climate. The interior sea of Japan presents less of a Mediterranean character, properly speaking, than of a vast canal traversing the Japanese archipelago which places the water of the Korean sea in communication with the water of the Great Ocean by the passage of Shimonoseki in the West between Japan and Kyūshū, and the straits of Bungo, of Naruto, at the South and at the East.

In the interior sea five basins can be distinguished by the promontories and the gulfs of the great lands of Kyūshū, of Honshū and of Shikoku, or by the charming groups of islands which they border. Those basins receive the names of the principal provinces whose banks they border.

The configuration of the coasts and the numerous groups of islands of the interior sea is in fact one of the most picturesque places of Japan.

These islands, small or large, deserted or populated, and thoroughly covered in luxuriant vegetation form the belt of the two great lands of Shikoku and of Honshū, of which mountains of great height can be seen.

The whole country offers a most agreeable aspect, because of the mountains covered in vegetation and the rivers which flow in great number.

In some southern provinces they are ignorant of the snow while in the north, on the contrary, winter is very harsh: nevertheless the four seasons are more marked in Europe than throughout the country.

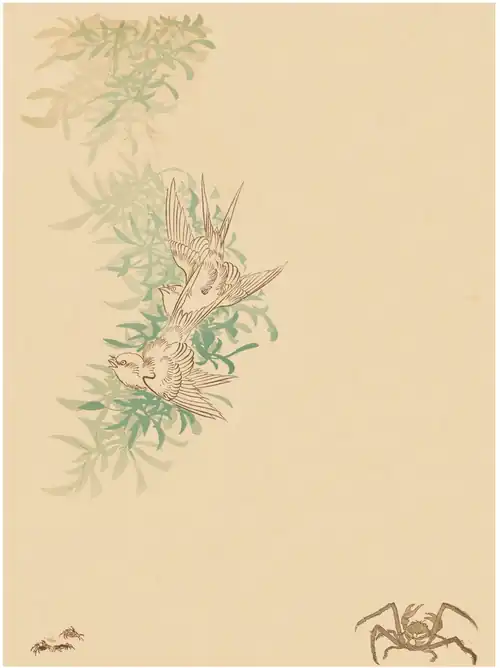

Spring in Japan is as delightful as in Italy. The sun’s rays seem to shine brighter and give off more heat than in France. The atmosphere slightly whitened by mist makes the flowers bloom, which are much more numerous than in Europe. One of the wonders of Japanese flora is the flowering cherry tree, which sometimes covers an entire mountain and gives it the appearance of a pink cloud. Birds and shining insects flutter about the flowering trees; all of natures seems to be celebrating!

It is very rare at this time of year to have a return to low temperatures, which are so common elsewhere.

On the other hand, summer begins with a long rain that sometimes lasts the entire fifth month. While this rain is favorable to rice cultivation and brings happiness to the peasants, it also engenders melancholy and sadness among the artists. How many poets missing the flowers and birds, raise their complaint to the heavens at being brusquely torn from such a beautiful dream of spring.

As soon as this heavy periodic rain has stopped, an intense heat sucks up the vapors from the ground and makes the atmosphere heavy and stifling.

Fortunately, this short period is replaced by dry, bearable weather, despite the great heat which persists until the first dew of autumn.

Autumn is heralded by the arrival of westerly winds that bring the first coolness and blow through the trees, imitating the sound of a storm.

Little by little the forests and mountains change their appearance and the leaves take on yellow tones of infinite variety, waiting for the frost, which, with the approach of winter, will soon cover the ground.

Autumn is the most pleasant season in Japan. The mild weather, the pure atmosphere, the bright moon, the easy walks, all make you dreamy and sentimental.

The complete fall of the leaves and the gradual drop in temperature signal the arrival of winter. But after this first cold, the weather becomes mild again during the tenth month, called “the little spring.” The great cold soon comes to destroy it.

The first snow is celebrated by nature lovers, who go to contemplate the strange appearance of the countryside.

Nothing is more beautiful than snow in Japan because of the picturesque mounds and trees that are nothing like the monotonous landscape regimented with straight trees. The admiration that one feels at the sight of snow makes some Japanese forget the cold; a servant, fearing to stain this beautiful white carpet, cried out one morning: “Ah! the new snow: these tea grounds, where shall I throw them?”

From another servant came this charming phrase: “Oh! please, madam, don’t send me to the market this morning, the little dog has painted the courtyard with his paws. I would never dare to erase this delicate painting with my country clogs.”

Daimyō Feudalism and Legislation

From an administrative point of view, Japan is divided into eight regions, comprising sixty-eight provinces, not counting the island of Yezo, which formed, so to speak, a colony.

The provinces are subdivided into 639 districts, owned by 260 daimyō who formed a feudal confederation at the head of which is the Shōgun, as civil and military lieutenant to the Mikado.

The law decreed by the Yedo government applies throughout the confederation, leaving the daimyō with administrative and judicial powers over their domains.

Thus the governor of a city or district is at the same time administrator and judge for all causes; it is he who pronounces sentences of death, crucifixion, or decapitation.

The prison was only preventive. Confinement to remote islands serves as punishment for political prisoners who have escaped the death penalty.

Legal suicide is the privilege of the nobility; we will discuss this further below.

The legislation, remarkably simple, is sufficient to punish the small number of criminals, which is far less than the proportion found among civilized peoples.

The feudal régime naturally necessitated the division into two classes, the nobility and the commonalty.

Hokusai.—Fujiyama, Sacred Mountain of Japan.

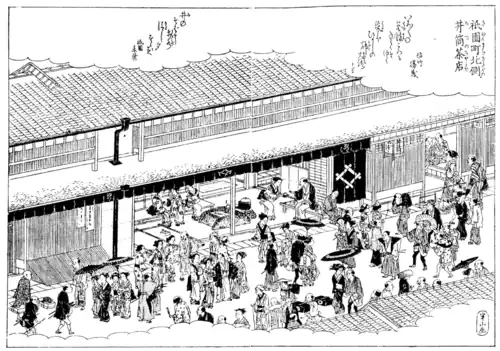

Hanzan.—A street in Kyōto.

Above the people is the Samurai. The Samurai are under the command of the Daimyō, who answers to the Shōgun, who in turn answers to the emperor.

The Daimyō exercise their rights without abusing them, and the Samurai are highly esteemed by the people. It is rare to see a nobleman commit an act of violence. The two swords he carries at his belt are used only for self-defense: moreover, it is considered cowardly to draw one’s sword without being offended.

In general, Samurai have impeccable conduct. They are sincere and devoted to their masters, polite to their friends, gentle and generous to the people.

Among them, the chivalric feeling is highly developed and caste honor is greatly respected.

Samurai spend their time studying and practicing with weapons. Civil servants are chosen from among them. Even today, it is mainly former samurai who form the progressive groups and are at the head of Japanese civilization.

Harakiri

A too great scholar is often deceived by the ignorant, just as honest people are more easily deceived. A great French work repeats stories about our customs from an ancient traveler which are inventions.

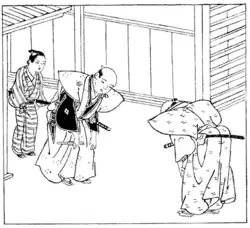

Sukenobu.—Samurai in Official costume.

In this book, harakiri is ridiculed in a witty but illogical manner.

Seppuku, commonly called Harakiri, is a solemn act where the life of a nobleman is at stake; it was a point of honor based on a very high feeling that introduced this custom into our culture. If one must end one’s life, it is preferable to do so oneself rather than allow oneself to be killed by another. This suicide is sometimes an excuse made to society by a man whose honor is compromised and sometimes a mercy granted to men-at-arms in the event of a death sentence. In the latter case, the official formality is indispensable as well as a privilege.

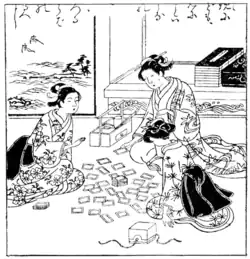

Sukenobu.—A card party.

It is too naïve to believe that we make a game of plunging a dagger into our bellies, unless you are convinced that we are brutes devoid of sensitivity.

In the Seppuku ordered following a judgment, a place is chosen where the solemn act is to be performed. The condemned man, dressed in the official all-white costume, sits on a rice straw mat. Two magistrates (principal and deputy), responsible for pronouncing the sentence, are present, as well as two assistants responsible for the execution and who are chosen by the unfortunate from among his friends.

A dagger blade wrapped in paper is placed on a white wooden sanbō that is brought before the condemned man. A profound silence reigns among the assistants kept at a distance. At this supreme moment the magistrate asks the unfortunate man for his last wish, which he pronounces

or written. Then he pulls aside the garment and, grabbing the dagger, cuts quite deeply into the skin of his stomach, from left to right. Immediately, the chief assistant standing behind him cuts off his head with a stroke of his sword.

The role of the assistant is to cut off life in order to spare the suffering of the man who has just accomplished a courageous act. The ill-informed author we have quoted says that an executioner waits with a sword in his hand to kill the condemned man, in the event that he hesitates to kill himself. This is inaccurate; no samurai has ever shown cowardice in such circumstances.

The Character of the Japanese

The general character of a nation of thirty-five million inhabitants is very difficult to portray accurately.

The southern Japanese are not at all like the northern Japanese. Only a few points are common throughout the country. These points are: love of country, filial love, devotion to one’s family, politeness, patience, order, cleanliness, and an appreciation for art.

The respect shown to scholars and artists is very great. Works of art are always moved with care. Likewise, everyday objects are handled with delicacy, and one can safely let any servant wash the most precious dishes. If she has not yet seen these objects, her instinct guides her. We are far from the indifference and inattention of certain foreign servants.

Travelers say that the Japanese have a cheerful character; let us say that we value being polite and pleasant. The first of our kings, Ōkuninushi, found that smiling is the source of happiness and fortune.

When his son Kotoshironushi learned the trade from the men, he followed his father’s advice and found that business was going wonderfully.

Faithful to these laws, the Japanese are very cheerful in appearance. Our scholars have commented on this as follows: the principle of harming no one applies to social etiquette. Bad humor being very contagious, it is inappropriate to disturb others because of oneself. One may have worries, but that is nobody else’s business; it is no reason to influence others. Hence, cheerfulness has become a habit.

But the Japanese are not lacking in other abilities.

The more reserved people are, the deeper their thoughts, because deep down, Japanese people are very thoughtful; they are also modest and cautious in conversation. Among friends, they are frank and affectionate; to the world they only express opinion if asked to address an issue. In this case they are more than interested. This reserved character is compensated by a brilliance that manifests itself in poetry and art.

The Japanese love pleasure, but they also work hard, and their taste for a luxurious life is less developed than in other countries, as a result of Confucian morality, which prescribes that everyone should be content with their lot in life.

Peasants are very honest, likable, and hospitable, and are well educated. They often have a more logical philosophy than city dwellers.

Women are very submissive to their husbands, but they are not their slaves. They enjoy their freedom. The law grants them rights. They know how to gain the upper hand through their gentleness, and they are generally excellent housewives and very faithful to their husbands.

Self-esteem is great among the Japanese. One can achieve anything by complying with this sentiment, but if it is injured, interest alone cannot restore the balance. Although there is no shortage of insolvent people, the word of honor is generally kept. One can safely entrust an important mission to a Japanese, and it will be fulfilled, even if means death. This characteristic is found even among criminals. I cite an example to affirm that the old tradition has not yet disappeared.

In 1879, a great fire broke out in Tokyo, and just as the fire was about to engulf the central prison, Mr. Onoda, who was then director, opened the doors and said to the convicts: “I will set you free tonight and save your lives, but promise me to return to this place tomorrow morning.” The next day, when the number of those present was counted, not one was missing.

Hanzan.—Interior of a Buddhist Temple.

Although we are as I have just described, we are not always good judges of ourselves. Some foreigners judge us quite differently. Mr. de Dalmas, author of “Les Japonais, leur pays et leurs mœurs,” has declared emphatically that the Japanese are not intelligent, that young students are incapable of embracing any comprehensive study, and that we are like the monkey who, having seen a watchmaker repair a watch, took it apart but was never able to put it back together. Mr. Georges Bousquet also judged us very harshly; despite this, I am pleased to be able to announce to these gentlemen that their writings have not succeeded in diminishing the great sympathy that the Japanese feel for the French.

The Religions

Our religions and our morals have been the subject of serious and in-depth study by Mr. Emile Guimet; to give an idea of these matters, it is enough to borrow a few lines from the catalog of his religious museum that he is going to open in Paris. Here is what he says:

“Japan has two religions, Shinto, the official national religion, and Buddhism, which was introduced to the country by Korean priests.”

Shinto traces its origins back to those of the Japanese people themselves, and in fact there is no other popular belief to be found at any point in the history of this country.

This religion recognizes a creator called the Master of Heaven and two auxiliaries named the Creator of the Universe and the Creator of Kami. (It is also said that one is a producer and the other a preserver.) The Master first created a subtle, light element that formed the sky, then a heavy, murky matter that was the origin of the earth. Then several divine beings, such as the Eternal Existence of Heaven, the Eternal Existence of Earth, etc., completed the work of creation. Finally, Izanagi and Izanami created the earth by stirring the matter floating in space with a spear; they then gave birth to the sun goddess, Amaterasu, and the lord of the land Susanoo, which was the origin of the emperors who reigned for thousands of years in Japan. The last descendant of this divine race was Jimmu Tennō, the ancestor of the current imperial family.

Shinto commands purity of life, physical and moral, obedience to the law, respect for the emperor, and finally, respect and love for one's ancestors.

Shinto does not worship idols. It considers divinity too great and too majestic to be humbled by giving it a material form. The temple, simply built of white wood, contains only symbolic objects, including the mirror, which represents purity.

The priesthood is hereditary in his family.

I will not elaborate on Buddhism here, as the public is more familiar with it than with Shintoism. I will simply say that Japanese Buddhism has remained purer than Chinese Buddhism.

There are six main Buddhist sects in Japan, one of which, called Shinshū, was founded in the thirteenth century by the priest Shinran and is the most widespread today. In this sect, priests are not required to be celibate or abstinent, and the priesthood is hereditary.

Japanese Buddhist books are translations of Chinese books and numerous Buddhist manuscripts from India, written in ancient Sanskrit, of which some temples possess precious collections. These works have all been explained and commented on by priests from various Japanese sects. Their number is considerable, amounting to eight thousand.

Now let’s go into the details of the practice.

No single individual professes two religions at the same time among other peoples, whereas the Japanese are both Shintoists and Buddhists, with the exception of priests.

The mark of respect shown to national deities and ancestors is the object of Shintoism.

And one escapes the sufferings of the soul by entrusting oneself to Buddhism.

There are a considerable number of Buddhist temples and convents and Shinto chapels in Japan, including 90,000 Buddhist and 128,000 Shinto shrines in 83,000 towns and villages.

In Shinto worship, each temple has its own parish, and the inhabitants of that territory must participate in its periodic festivals, while in Buddhist worship, the inhabitants of all territories are free to belong to any sect and, in the event of a ceremony, go to the temple whose cemetery contains their family tombs.

Despite this large number of temples, every family, rich or poor, has a Buddhist pagoda, where the inscriptions of all family members from the first ancestor to the last are kept.

These inscriptions contain the names, dates of birth and death, and on the corresponding anniversaries, an act of veneration is performed in honor of each deceased member.

In religious families, the pagoda is open every evening and all practicing members come there to pray.

In some families, this service is entrusted to priests.

Instruction and Education

The principles of education were given to children by their parents until today. This was called family garden education. It consisted of:

1st. To learn to read and write the Japanese alphabet and the most useful Chinese characters;

2nd. To instill in the child the moral principle of Confucius, which can be summarized as duties towards one's teacher, parents, and friends.

It was customary for parents to tell their children in the evening after dinner all sorts of national legends and stories about China, which could serve as a model of conduct, and the innocent little ones took great pleasure in listening to them.

When a child misbehaved, he was threatened by being told that he would not hear this or that story, and he obeyed immediately. Thus, before reaching the age when one learns to read, children were already aware of many circumstances of life. They were not only told stories of Bluebeard and Buddhist miracles, but also the biographies of famous men.

Family education is of prime importance, because for a child, no one is as knowledgeable as his father or as good as his mother, and he believes everything he is told. Although experience changes ideas at a certain age, the first ones that have been impressed on a young brain are difficult to erase.

In the absence of today’s universal and compulsory education, there were private institutions run by teachers who received students.

Not only were they responsible for teaching them to read and write, but they also taught them politeness and etiquette. The teacher was a second father to boys, and a second mother to girls.

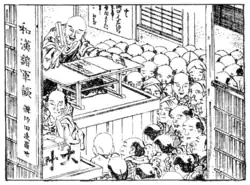

These institutions were called Tera “Buddhist temple” and the students were called Terako “children of Tera”; education was originally provided by Buddhist priests.

Higher education was provided by scholars or in the colleges of Daimyo.

There, they studied the books of Confucius, the history of China and Japan, literature, poetry, and various other subjects, to the point that a Japanese scholar knew China as well as an eminent Chinese.

The Yedo Academy was the center of literature and science.

who went to Japan every time there was a change of dynasty or when wars destroyed everything.

Since the sciences of Europe were unknown, the main subjects of study were philosophy and history. Literature and poetry were highly appreciated. Some scholars were even brilliant mathematicians, but this science was not as widespread as the others. Lacking the positive sciences, we devoted our time to belles-lettres. All educated Japanese are poets.

Dwelling

The appearance of a Japanese city is completely different from that of a European city; strictly speaking, it is neither a city nor a village.

In Yedo, for example, the trade and entertainment district resembles a fairground, while the aristocratic districts form a sort of immense villa. The Shogun’s residence is located in the Shiro, a fortified enclosure made of granite and surrounded by ditches. The residences of the daimyo, called Yashiki, are veritable palaces. Temples are always located in the middle of a park. The regular row of bourgeois houses is interrupted by belvederes raised to watch over fires.

All the houses are built of wood; they are small, low, light, and charming. Stone is used only for the foundations. The partitions of the rooms are made of very light masonry. The roof, placed directly above the first floor, is covered with tiles or small pine boards; it protrudes by about one meter, which adds to the elegance of the building’s style. There are no windows; instead, there are large openings which close with double sliding doors, some of which are made of wood and called amado (rain doors), replacing shutters, while others, called shoji (wind doors), are made of fine, thin wood covered with light paper which serves as windowpanes.

Three- or four-story houses are very rare. The first floor of wealthy houses is reserved for reception rooms. In this case, a beautifully crafted wooden balcony surrounds these rooms, offering a lovely view of the street and the garden, which always accompanies the dwelling.

In a populous neighborhood, the garden is located behind the house. The first floor of small houses, being too low, forms only an attic; in any case, it is the ground floor that one usually inhabits. It should be added that most Japanese people own the houses they occupy.

As in France, the number of rooms varies according to the size of the house.

So let’s take the middle class.

Let us, for example, enter the home of my partner Mr. Wakai, who lives in one of the nicer neighborhoods of Yedo.

At the entrance to the house there is a sliding door, made of artistically crafted latticework. Behind this door is a room with a dirt floor at sidewalk level. Once inside this square room, you say “gomen-nasai,” which means “excuse me.” One then takes off one’s shoes, leaves them on a stone step at the entrance, and goes up to the apartment. Geta and zori are always found on this step. The zori is a thin straw sole with a padded sheath in the shape of a spur that holds the foot in place; the geta has the same shape as the zori but is made of wood and is five to ten centimeters high.

The first room is the antechamber, which leads to the tea room opposite, the living room on the left, and the maid’s room on the right. All these rooms are covered with tatami, thin white mats lined with tightly woven rice straw seven centimeters thick. A tatami is about the width of an Oriental rug, always the same size, and cut at right angles. The size of a room is therefore determined by the number of tatami mats that can be laid in it. The extreme softness of these mats produces a very pleasant impression when one walks on them.

The lady of the house is usually in the tea room, so one enters this room and greets her by placing one’s hands on the ground and bowing one’s head. If it is a woman who is visiting, the greeting lasts quite a long time and, especially in the provinces, involves a genuine nod of the head accompanied by polite words spoken in a low voice.

In the tea room, opposite each other, are the Shoji, large openings through which the room is lit, and the Karakami, whose panels all connect to the adjoining rooms. The Karakami are sliding doors covered on both sides with strong paper, silk, or paintings. The size of the Shoji, Karakami, and Tatami is generally the same. The study is to the right of the tea room and the bedroom to the left. The partition connecting to the antechamber forms a 30-centimeter recess for a large shelf that replaces the European sideboard. The tea room serves as a dining room.

The shelf is irregularly divided into open sections and sections closed by small doors, some made of rare, natural wood and others covered with drawings or engravings. The shelves hold tea utensils, including small cups, tiny teapots, vases of various sizes, water jugs, cake boxes, etc.

A hibati (brazier) made of precious wood lined with metal contains ashes, in the middle of which a few pieces of charcoal burn. An artistic cast iron kettle called tetsubin, placed over the fire on a tripod (gotoku), always contains boiling water.

A tabacobon (tobacco tray) is provided for smokers. In Japan, especially in large cities, women smoke tobacco, but opium use is unknown here.

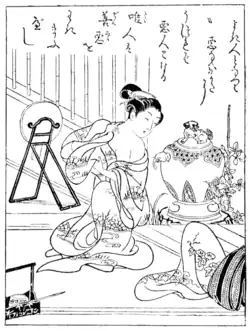

In the bedroom, there is neither bed nor chair; a large alcove closed off by karakami screens conceals the bedding, consisting of a mattress spread on the floor for the night and one or two enormous cotton or silk robes that serve as blankets. A small cushion placed on a lacquered stand serves as a pillow. In the morning, all these objects are put away after being thoroughly beaten.

Paper screens are used to surround the bed and replace curtains, which are unknown in Japan.

In another alcove are lacquered or natural wood furniture, the large drawers of which contain clothes, and the small ones, papers.

A small bathroom, next to the bedroom, has a very elegant appearance. The window, seventy centimeters high and projecting outwards, forms a dressing table. This window has a very artistic latticework made of small bamboo. A sort of copper cauldron serves as a basin for washing. A wooden bucket encircled with thin bamboo holds water that is poured out using a long-handled ladle.

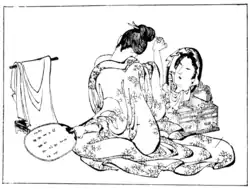

Women’s toiletries are kept in a small black and gold lacquered cabinet. A metal mirror is placed on a lacquered easel and covered with a piece of embroidered silk. This small cabinet also contains women’s jewelry, consisting of tortoiseshell combs, a variety of gold lacquer items, and hairpins made of gold, silver, tortoiseshell, etc., finely engraved with flowers and various motifs.

Moreover, these are the only pieces of jewelry worn by Japanese women.

A small hallway leads from the bathroom to the kitchen. The flooring in the latter room is made of fairly wide pine planks, lightly lacquered; it shines as much as a well-waxed floor.

The sink, which is generally made of wood, is much larger than in France.

A huge stoneware pot serves as a fountain, and the water arrives through a bamboo pipe connected to a wooden cube, which serves as a reservoir and is placed near the well in the courtyard.

The stove is made of masonry and copper.

The pots and pans, made of iron, copper, and terracotta, are stored on a shelf. The entire kitchen gives the impression of being remarkably clean.

The room adjacent to the kitchen connects via a staircase and a corridor to the Kura, a masonry building that would not burn in a fire. It is in the Kura that precious objects are kept, wrapped in small silk bags and stored in small square white wooden boxes bearing an inscription.

Harunobu.—The Toilet.

The living room overlooks a small, picturesque garden on one side, while on the other side there is a 20-centimeter-high alcove called a tokonoma (place of honor). This is where a lacquered shelf decorated with art objects or various other precious items is placed.

On the wall of the tokonoma is hung the kakemono, a painting or piece of poetry framed with pieces of old fabric, chosen according to the season, the occasion, and the guests being received.

Two paintings are never hung at the same time, unless the kakemono consists of two or three parts.

The objects placed on this platform must be chosen with taste, so that they harmonize well with the kakemono, the main decoration.

A vase decorated with a few branches of flowers is placed or hung at a certain studied height, unless the painting itself depicts flowers.

A flower vase should be made of bronze or ceramic, but greenery can be placed in porcelain decorated with colors.

Hokusai.—The Hairstyle.

You are in the middle of summer, a snowy landscape harmonized with jade and crystal objects is as pleasant to see as, during winter, a spring landscape accompanied by a bronze vase with flowers. Also, we take care to vary this little decoration according to the seasons, so that it always produces a pleasing effect on the eye and the mind.

Such being our national taste, it is very difficult for us to accustom ourselves to the rich and dazzling furnishings of Europe.

One of the finest examples of a Japanese house belongs to Mr. Hugues Krafft, author of Notre Tour du Monde. This charming little house, which he commissioned during his trip to Japan, was built on his property in Jouy-en-Josas in the middle of a large park designed in the Japanese style with great taste.

An excursion through the Far East can now be made just two hours from Paris.

Style of Dress

The traditional costume is still worn today by most Japanese people, even in large cities, with the exception of civil servants.

The rich brocade and embroidered robes, which are admired abroad, are far from being everyone’s attire. Only nobles or the wealthy can afford to wear these expensive garments.

In general, ordinary people wear cotton dresses in very sober colors. Those who can afford it wear silk dresses, but brightly colored clothes are only worn on special occasions. Mr. Hugues Krafft, who observed all these details, says that “the clothes of the Japanese people are always in discreet colors. Bright colors are only seen in the clothing of children and young girls.”

Japanese clothing consists of wide, open, layered robes that are fastened with a cloth belt. Men’s and women’s costumes are very similar in cut; but they are easily distinguished by the style and choice of fabrics, which are more attractive in design and color for women. Moreover, a woman’s robe is always lined in red, pink, or blue.

The man’s belt is made of dark fabric and is only nine centimeters wide. The woman’s belt, on the other hand, is made of generally rich silk fabric and is thirty centimeters wide. It goes twice around the waist and forms a large knot.

In winter, working-class men wear a leotard and blue canvas tights under their robes, and women wear one or more padded mantles. Bourgeois people never go out without a leotard and trousers.

Hairstyles are another particularity of Japanese dress. It is well known that hats are not worn in Japan. Men shave their heads above the forehead and comb their hair back over the crown. Women, more coquettish, did not want to submit to this singular custom and kept their hair. However, hair, always black and thick in Japanese women, requires a more voluminous hairstyle than in European women.

Engraving by Gillon.

Utamaro.—The Japanese Kitchen.

In addition, it is adorned with tortoiseshell or lacquer combs and pins made of gold or silver, chiseled and inlaid with coral or precious stones. The hairstyle itself was therefore one of the main ornaments of women’s attire, and the idea of wearing a hat never occurred to them.

Leather shoes are not worn in Japan. They wear a kind of sock called tabi, made of cotton, with separate toes, and when going out, they wear the geta that I mentioned earlier. It should be noted that Japanese women do not have bound feet like Chinese women and that they have as much freedom as men to come and go outside their homes, but they love the indoors so much that they rarely go out.

The official costume of the imperial court is very loose-fitting and has a unique cut. I cannot describe it without making this article excessively long.

At the Shogun’s court and among the Daimyo, the official attire consists of kami-shimo (top and bottom) and montsuki (coat of arms); the latter is usually black or plain in color, with the family crest in white. The kami, also called kataginu (shoulder costume), is made of fine light blue cloth, printed with tiny white designs. Its square shape on the shoulders is somewhat reminiscent of a boat sail (See p. 70). The shimo, also called hakama, is a very wide pair of pants, made of fabric matching the kami, with small vertical pleats. It resembles a pleated skirt.

In official attire, the two swords worn on the left side of the belt had to have similar mounts. It was also essential to carry a fan and a medicine box called an inro.

The parts that make up the mounts of the swords are either gold, silver, iron, or copper, or one of our own special alloys. They are true masterpieces of the art of engraving, which only Japan has developed to such a high level. Medicine boxes are mainly made of very fine lacquer. Some of these pieces are remarkably beautiful. The buttons that attach the medicine box to the belt are called netsuke. These are made of wood or carved ivory representing a wide variety of subjects.

Of all that Japan has produced, what most strikes artists is the color of the dresses. Some are made of silk fabrics with a wide variety of designs and colors, while others are embroidered with all kinds of subjects from painting. Dresses are not worn solely for the sake of wealth and vanity; above all, people seek artistic enjoyment in clothing. Several great artists of the seventeenth century, such as Korin, Moronobu, Yūzen, etc., contributed to this perfection in clothing. They created dresses that are true works of art.

The sword fittings, lacquerware, ivory and wood carvings, fabrics and costumes, etc., of which I have just spoken, form an essentially Japanese art, which remains a subject of admiration for artists and connoisseurs.

Meals

Japanese food differs significantly from European food in that it is not based on the principle of fat. All dishes are prepared with shōyu, an essentially Japanese sauce obtained by fermenting water, salt, rice, wheat, beans, etc. We completely lack butchery and charcuterie due to our Buddhist education, which commands respect for the lives of animals.

We eat rice cooked simply in water instead of bread. Fish and vegetables are very abundant. Poultry and game come next. We don’t have cabbage, but we do have many other vegetables unknown in Europe, including turnips that weigh several kilos and have a very delicate flavor.

Although everything is seasoned with the same sauce, there is considerable variety in the dishes. The kitchen is always kept extremely clean. Everything is washed thoroughly and repeatedly. Wine is not drunk, but tea is. Sake (rice wine) is a ceremonial drink, for celebrations and enjoyment, and is not served with everyday meals.

Meals are served in the tea room. There is no high table like in Europe; everyone eats on a gozen, a lacquer stool that reaches to the knees; each guest has his own gozen on which there is a bowl of rice, a bowl of soup, one or more dishes of meat and vegetables, and a small cup with a few pieces of turnip or other salted vegetables. A pair of wooden, ivory, or silver chopsticks, the size of a pen holder, replaces the European fork. Knives are not used; everything is cut up by the cook. Spoons are not necessary; soup bowls are brought to the lips. For distinguished guests, dinner is often preceded by a first feast where sake, sashimi, and many other dishes are served. Sashimi is a fillet of very fresh raw fish, cut into small pieces and eaten with shōyu, seasoned with grated horseradish. The gozen arrives only at the end of the meal, but the appetizers are so copious that many guests, especially sake drinkers, forget to touch their rice!

Music and dance often accompany a banquet, especially when it takes place in restaurants. In this case, musicians and dancers called geisha are invited, whose profession is to entertain the audience. Geishas are young women, usually intelligent and witty. They respond to invitations to liven up parties for a fixed fee, which varies according to their class. They are good conversationalists and very cheerful, but they are not “loose” women. On the contrary, they are required to have a good reputation in order to have a large clientele. They live freely wherever they please, but by the nature of their profession they are generally found in the districts with the larger restaurants and tea houses, which many people misunderstand, because the role of these houses is the same as that of the restaurants and cafés of Paris.

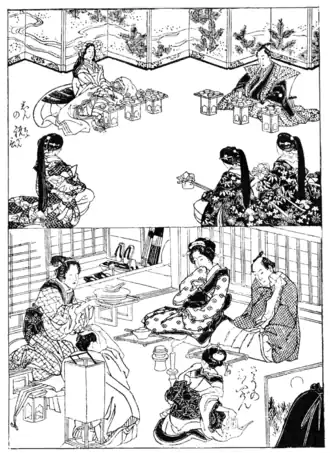

A Wedding of the Nobility. A Wedding of the Commoners.

(Sake Ceremony.)

The Wedding

Marriage among the Japanese is neither a union of love nor a dowry deal. However, it is one of the four solemnities of life, along with birth, death, and ancestor worship. Marriage is a duty imposed on men in order to preserve the lineage of their ancestors and to propagate the family. Any idea of passion must therefore be discarded; young people must not be allowed to choose freely. This task is left to the parents, who, having more experience, know life better. Once their choice has been made, the marriage can take place, if the boy and the girl like each other and agree to submit to their parents' proposal. Therefore, it is not the children who ask the parents for consent to marry, but rather the parents who ask it of the children.

When two families who wish to arrange a marriage do not know each other, an intermediary is used to reach an agreement for both parties, and when everything is arranged for the union, there is an interview, where the future spouses see each other for the first time. The formal custom is not to decide anything at this moment. Following this interview, if one or the other of the fiancés gives a negative response, everyone is relieved of the inconvenience. But this case only exists in large cities like Yedo, Kyoto, Osaka, etc.

According to the intermediary, all the girls are beautiful and virtuous, and all the boys are intelligent and hardworking. But that doesn’t mean they can’t make mistakes! If the marriage is unhappy, divorce can be granted.

Among the nobility in particular, where the number of families of similar standing is quite limited, marriage is often contracted independently of the will of the future spouses, who, sometimes engaged since childhood, do not know each other.

The priest does not intervene in marriage, religion having nothing to do with a commitment that is not definitive since divorce can break it. Moreover, in our opinion, we do not like to see in a joyful ceremony the priest who will be called upon in moments of sorrow.

The civil act consists of informing the city halls of the husband and wife's districts in writing of the marriage.

The magistrate removes the woman’s name from his civil registry and sends it to his colleague, who adds it to his registry under the husband’s family name to legalize the marriage.

If this formality is not fulfilled, the marriage is null and void.

If one follows the customs, there are many formalities to be fulfilled; but the ceremony is simplified according to wealth and position. In the engagement the man must give a gift to the woman. Acceptance of this gift is proof of mutual agreement, and the wedding date is fixed.

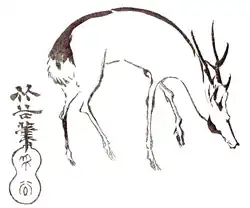

Facsimile of a drawing by Korin, the Japanese Impressionist Master

The betrothal gift consists of two silk robes, white and red, three barrels of sake, and three fish; but in the poorer classes this gift is reduced to a cotton robe.

There is no dowry, but the bride brings enough to set up her household in clothing, furniture and various everyday objects.

In a rich wedding, these objects that are carried constitute a veritable procession.

The man doesn't need to buy anything during his life, because fortunately for us, fashion doesn’t change as often in Japan as it does in Paris.

The wedding ceremony consists of performing the Sakazuki ritual (special sake cups). The main room is the chosen venue; the bride first takes the place of the lady of the house, and the groom sits in the place of the main guest, as is customary. The man wears formal attire and the woman a white dress. Relatives and friends take their places in the order indicated.

The ceremony is presided over by a lady-in-waiting among the nobility or by an intermediary among the common people. Three sake cups are placed on a special stand before the man. The man first takes the first cup and drinks three times. Then he begins the second cup, which he offers to the woman. She drinks from it three times, then begins the last cup and offers it to the man, who finishes it in three goes. Once this is accomplished, the marriage is concluded.

Then comes dinner and a remarkably cheerful party.

The newlyweds retire at the beginning of this part of the ceremony, thanking the company for their warm congratulations.

They are then led by the maid of honor to the bridal chamber, while the party continues in the living room.

Theatres and Shows.

In 1878, on the occasion of a Japanese performance, Mr. Philippe Burty gave a lecture on Japanese theatre for the first time in Paris, at the Théâtre de la Gaité. Unfortunately, it was not printed. I am returning to this subject, continuing the author’s intention.

In Japan, there are several types of public halls where you can spend the evening or even the whole day. Some of them open in the morning.

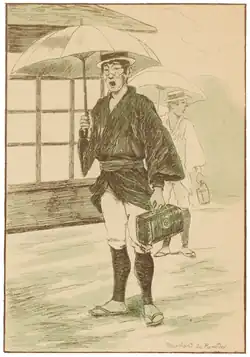

A Dandy.

Seller of Remedies.

A Civil Servant.

Singers on the Road.

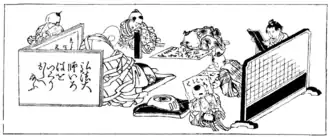

Apart from the theatres themselves, called Shibaï, there are commentary rooms (Kôskakou) and meeting rooms (Yosé).

In the commentary rooms, roughly analogous to lecture halls, speakers recount the highlights of Japanese history and the lives of famous men. Listeners are moved, educated, and carried away for several weeks. Each speaker, after speaking for one or two hours, is careful to postpone the rest until the next day, stopping at the most interesting passage. The education of the people is largely carried out in these rooms.

The Yosé (meeting rooms) are divided into several categories: rooms where people laugh, rooms where people get excited, rooms where people cry, where people are amazed, where people are entertained, and where people are frightened.

In rooms filled with laughter, the orator tells the audience stories that are often nonsensical, as indicated by the term used to describe them: Otoshibanashi (lost tales). Gestures and grimaces play a large part in them. As for the subject, it is sometimes a monologue, sometimes a small vaudeville play in which the orator plays all the roles.

The rooms where people are passionate about love only deal with novels, and the speakers tell stories called Ninjobanashi (love stories). These rooms are mainly frequented by women.

Those where we cry are musical. Our monotonous music admirably accompanies sad and dramatic songs. These are very touching plays, called Jōruri, from the name of a princess whose romantic story provided the subject of the first play performed in Japan.

The rooms where people are amazed are for children. Magic tricks are the subject of the show. As for the rooms where people are frightened, one hears stories of ghosts, murder, etc.

Dancing, singing, and lively music return to entertainment venues. They are exactly like the café concerts of Paris.

The halls I have just mentioned are, in large cities, very numerous. They all have more or less the same construction plan. They are empty rooms with no furniture, covered with thick tatami mats, on which the audience sits cross-legged. There are no chairs or benches. Sometimes there is a balcony and boxes, but very rarely. The hall is rectangular. At the back is the stage, four meters wide, two meters deep, and one meter above the floor. A curtain closes off the stage and opens from right to left. The backdrop consists of richly decorated karakami panels. When the curtain opens, the artists squat on the stage and only begin their roles after greeting the audience and welcoming them.

Storytellers sit at a small Japanese table only thirty centimeters high, on which stands a cup of hot water to quench their thirst and the manuscripts they consult when their memory fails them. Novel and monologue storytellers have no table. They use no other props than a fan they hold in their hands. Musicians arrive naturally with their instruments, and drama singers have a book placed on a richly decorated lacquer music stand. They are also given a cup of hot water.

There are usually two performances, one in the afternoon and one in the evening, with the stage lit by two tall candlesticks placed in front of the performer, who extinguishes the candles himself. The audience, a mix of men and women, sits on the floor, and the first to arrive has the right to choose the place he likes. In each room, small cushions are rented for seating; tea, cakes, and fruit are sold.

Each room has its own entrance and drink prices. There are no tips. Here are the average prices at Yedo: entrance, five sen; cushion, one sen; foot warmer in winter, two sen; teapot with a cup, one sen; a box of cakes that can delight an entire family costs four sen! As you can see, it is possible to enjoy a whole evening of entertainment at a small cost.

Besides these halls, there are circuses, acrobats, wrestlers who give performances in amphitheaters.

The theater itself, also built of white wood, is a vast square hall. The stalls are divided into several compartments, each capable of holding six people. Around the stalls are the first and second boxes. The front boxes, which are not the best in our country, given their distance from the stage, are called deaf boxes.

The curtain is drawn from right to left. A man responsible for operating it takes hold of one end and crosses the entire stage, gathering it up in his arms. The set is partly painted, but unlike in Europe, we do not see the interior of a living room with one side open to the audience. Thus, to depict a house in a garden, the whole stage shows a garden with a house rising in the back and middle, exposing the side of the rooms in which the action takes place. This house is made of timber framing that is easy to assemble and disassemble. However, this work requires much more time than changing sets in European theaters, and consequently the intermission is longer. Convention plays a large part in Japanese theater, as it does everywhere else. Thus, thunder rumbles to shake the sky, a traveler arrives soaked to the skin by the storm, his umbrella is blown away by the wind, but during this storm none of the branches on the set’s trees move, not even the natural ones.

The scene change is carried out in two ways: either the scenery is painted on a curtain that is dropped to the ground, revealing the background scenery, or the stage itself rotates on an axis without the actors having to move. This circular stage facilitates the immediate transformation, because the circle of the floor is divided into two sides by means of a vertical partition that forms the backdrop.

Several trapdoors are installed on the stage for appearances, and the actors stand skillfully on them as they do in Europe during this movement of ascension or descent.

A quintessentially Japanese thing is the path called the flower road, a meter and a half wide, which crosses the theater from the back to the stage. If the stage represents a dwelling, the outside world arrives by this path and the actor, crossing it, walks, stops, and reflects in order to inform the audience of his intentions and plans.

Only men appear on the Japanese stage; female roles are played by actors who specialize in them. The actresses so charming in Europe, and especially in France, are entirely ignored by our audience. Our actors who play female roles are always dressed as women, even when going outside. One day, it is said, during a walk in town, a famous actor felt ill. He was taken to a tea house and the doctor, who was summoned in haste, attributed his indisposition to a purely female accident.

Actors paint their faces and transform themselves completely according to their roles. For this purpose, they always have their beards and eyebrows shaved. The costumes they wear are generally very rich and colorful, but in some roles, they are the very embodiment of truth.

The Tokugawa government in the seventeenth century prohibited men and women from appearing together on stage and authorized theater as a public institution, intending to encourage good and correct vice. Based on this principle, the characters in most plays were either extremely virtuous or extremely vicious. Some authors made a more serious look at social mores and created comedy.

Music plays a part in every play. They almost always sing about love and pain, as well as stories told by a character recounting his past. The roles are generally performed with great talent. Some actors are as refined as the best performers I have seen in Paris.

Fairies also play a part in our plays. Ghosts and spirits are depicted in a highly ingenious manner, to the great terror of the spectators. A fight, an assassination, or harakiri does not take place without bloodshed. By a clever artifice the artist in these scenes carries a paper or oilcloth bag filled with red and attached to the place where the dagger is to strike.

The stage is lit by candles, some of which are planted on long-handled wooden candlesticks held by men dressed in black from head to toe, who follow the actors’ every move. The audience is supposed not to see them, nor are the prompters, who, in this invisible costume, attend the first performances.

The room is lit by a series of uniform lanterns hung at equal distances in front of each box, at the expense of the teahouses, which have the right to decorate them with their coats of arms. Those with the most lanterns are the busiest. It had not occurred to us to light a room during the day, as is customary in Europe. Gas having been introduced a few years ago, this primitive originality has disappeared today.

A Japanese play consists of eight to twelve acts and several scenes, ranging in number from twenty to thirty. The performance begins at seven or eight in the morning and ends at ten or eleven at night.

A Meeting Room.

In large theaters, as well as in reading rooms, people smoke, eat, and drink. During intermissions, the cries of vendors selling programs and refreshments make a deafening din. People in the cheap seats buy their meals from these vendors. Those who can afford it are served by the tea houses. Cheap seats start at ten sous. One of the best first-class boxes costs fifteen francs. But the costs of the tea house rise quite considerably: you had to pay around fifty francs per box to be treated like a lord.

Tea houses are located in front of theaters and occupy a large part of the street. They have a clientele in town to whom they send the programs for each new play and receive ticket orders, which are always made one or two days in advance. Note that I am talking about a few years ago and that at that time we did not have newspapers. Sending out programs was therefore essential to inform the clientele of the plays that were to be performed.

Japanese Art.

I have saved this important question of Japanese art for last, which professional duty obliges me not to pass over in silence.—It is very difficult for me to speak of it in the little space which I have left. I am forced to only touch upon it, and I can offer to the reader only what is, in my mind, a too incomplete exposition. To treat even summarily a subject of such importance, it would be necessary to devote an entire article to it.

To those who wish to study it more fully, I recommend the magnificent work of Mr. L. Gonse L’art Japonais which is an authority on this subject.

Japanese art dates back to the most remote antiquity.—Although it borrowed its methods from the Chinese School, it differs from the latter in that it draws much more inspiration from nature.

As I said above, the Japanese compensate for their reserve by the brilliance they give to literature and the arts, and it is there that we find the expression of their feelings. We have seen that their general character is gentle and cheerful, so our art is charming and full of verve.

The only thing he lacks is the ability to accurately render nature.

An exact copy is completely foreign of Japanese artists, who prefer to give free rein to their poetic fantasies. Imagination dominates artistic works, which does not prevent them, on the contrary, from rising to heights that will never be reached by those for whom photography is the last word in painting. Thus, our artists are especially appreciated by those who know how to read the mysterious and universal language of art.

A Ceremonial Meal.

Oil painting is unknown in Japan; painting is done on silk or paper using Indian ink and watercolors. The frame is made of old fabrics and arranged in such a way that it can be rolled around a stick whose ends are made of ivory or hardwood. These paintings are called Kakemono (thing to hang) because of this fashion of hanging the painting on the wall.

History has handed down to us the names of many ancient artists, but we no longer have any trace of their works. It is only from the ninth century onwards that we find specimens considered authentic. The god Dzizo painted by Kanaoka, which is reproduced in Art Japonais, is one of these precious documents. It is painted very finely on silk with warm colors and has a very strong character; in this piece, we find certain points of contact with Indian art and especially with Byzantine art.

From the tenth century onwards, the Takuma school, which specifically dealt with Buddhist subjects, and the Tosa school, which applied itself to the painting of customs, flourished. The fifteenth century produced many great artists: Meitchô, Shubun, Sesshiu, and Kano left us with admirable works. From the seventeenth to the eighteenth century, several schools were created. Moronobu was at the head of the realist school, which deals with popular customs; Korin stuck to the whole and the broad outlines; Okio dealt mainly in flowers and birds from nature; finally, at the beginning of this century, the famous Hokusai produced a considerable number of drawings that form the most complete series of studies of all subjects in Japan. These drawings, which were engraved and printed in black and color, are highly sought after by Parisian art lovers.

Buddhist Priest teaching the alphabet to young children

Japanese painting, despite its incomplete method, has managed to bring to life both nature and imagination with its brush. Also, the boldness and flexibility of the touches, the accuracy and elegance of the lines, the variety and harmony of the tones, often rendered in ink alone, constitute a particular characteristic of the Japanese school.

Since amusing subjects have more readily attracted the attention of foreigners, some people consider Japanese painting as pure fantasy. Others believe that we have only caricaturists; this is a serious error: what we admire, on the contrary, are the serious and characteristic works inspired by a sober taste and a lofty sentiment.

Besides painting, we also possess a very rich decorative art. Ornamental motifs are extremely numerous and are not confined to the European School. Our decorative art is perhaps the most varied in the world, and its limits are unknown, for we are constantly discovering new motifs borrowed from all of nature, and it is surprising to see that spider webs and bird footprints have provided the most charming ornaments.

The best way to know these reasons is to

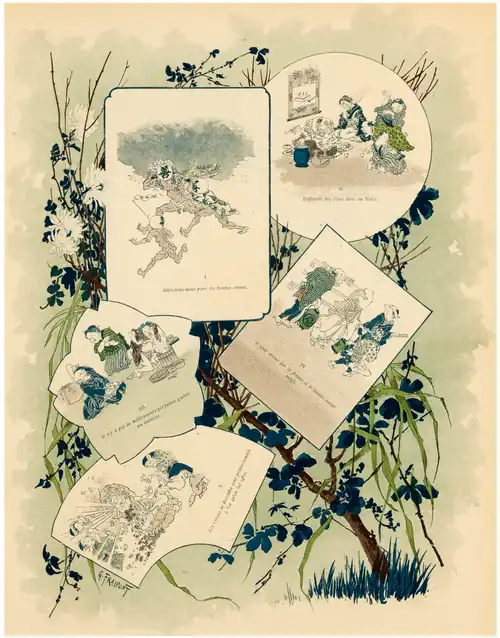

Ch. Daux—Japanese Fantasy.

Some Japanese Proverbs (Extracted from Cent proverbes japonais, translated by Steenackers).

make a collection of the prints that once formed our popular images and which still reach Paris today. Such a collection has the dual advantage of not taking up too much space and of containing the whole of Japanese life. One collector has counted more than six thousand different designs to date.

The plates do not exaggerate when they reproduce the designs of the dresses; the fabrics that form them are no less rich. We find ourselves before marvels of color and design of a majestic tranquility and incomparable beauty.

For several centuries, silk weavers were required, each year, as a tax, to present two pieces of fabric to the court of the Mikado. This custom was very favorable to the progress of our crafts because of the rivalry between artisans who created new designs. The Maheda family’s collection of antique fabrics already included several thousand first-rate pieces at the end of the sixteenth century. This collection has been continually expanded since, and has the reputation of being absolutely marvelous.

Sculpture, mainly in wood, comes in three different forms: Buddhist idols, masks for Nō representations, and netsuke (buttons which hold the inrō or snuffbox to the belt).

Idols, sculpted to be worshipped, are very beautiful but they cannot please everyone.

Masks, on the contrary, are very interesting because of the power of their facial expression. They belong to our great art and the beautiful masks hold their place perfectly alongside European sculpture.

The netsuke is a small, fine, delicate sculpture, crafted with great wit and imagination. It is made of wood and ivory. The subjects are generally lively and more amusing than those found on our trinkets. Some unique pieces are as beautiful as large sculptures.

Among our art objects, lacquer deserves to be cited as the true glory of Japan. Its existence is very ancient. The treasures of Nara include gold lacquers from the eighth century that are remarkably beautiful. Specimens prior to the sixteenth century are rare and sought after. Paris has collections that consist mainly of lacquers from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century. These are perfume boxes, writing boxes, medicine boxes, and various small pieces of furniture. They are mostly made of black lacquer decorated with gold powder designs, or entirely in gold or silver, or gold on gold, etc..... Red lacquer and other colors also exist. The merit of lacquer is that it is light, strong, beautiful, and unalterable. What is also particular to our lacquer artists is that they have invented a considerable variety of gold tones and have used this metal to create objects at the same time rich, elegant and discreet.

Many lacquer objects have been sold to Europe and America over the past fifteen years. They are becoming increasingly rare in Japan, but they still sell at a very low price compared to what they cost, not to mention their great artistic value. This is because there are only a limited number of enthusiasts who are interested in our art. However, these objects will soon become better known and will later attain great value. Only then will people want to own them and pay ten or twenty times more for them, without being able to build a first-rate collection. For Japan will want to buy back from Europe the objects it has carelessly disposed of.

I would also like to talk about ceramics, engraving, saber mountings, and various other branches of art, no less important, but I am forced to stop. I strongly encourage those interested in our art to visit, if they have the opportunity, the remarkable collections of Messrs. Edmond de Goncourt, Henry Cernuschi, de Montefior, Philippe Burty, Charles Haviland, Théodore Duret, Louis Gonse, Ch. Gillot, S. Bing, etc.

It is time to finish and take leave of the readers who were kind enough to have followed me to the end. I will consider myself happy if in this article I have succeeded in driving off some of the false ideas that everyone has about our country, and I will have achieved my goal.

Tadamasa Hayashi.

Some Japanese Proverbs

Extracted from Cent proverbes (On page 85), by Francis Steenackers and Ueda Tokunosuke.

E. Leroux, editor.

I

Zen wa Isoge.

Let’s hurry up for the good things.

When an opportunity arises to do something pleasant, you should seize it eagerly because it does not come along every day.

The drawing depicts good spirits running through the clouds carrying one of those meals that are customarily served at weddings, which is equivalent to saying:

“Since everything is agreed upon and our marriage is decided, let us hurry to avoid any obstacles that might arise.”

II

Nuka ni Kugi

Hammering nails into Nuka.

(Nuka is the name given to the debris that remains at the bottom of mortars when rice is purified.)

This expression is used figuratively when the person being given advice is determined not to take it into account.

A father is scolding his son, who has exasperated him with his bad behavior and extravagant spending.

The mother cries at this scene.

The young man listens, thinking of something else, his pose limp and effeminate.

Instead of men’s clothing, he wears women’s clothing from one of the houses where he spends his life.

A family friend tries to calm his father’s anger.

A kid who witnesses the scene takes advantage of the fact that his boss isn’t looking at him to stick his tongue out at him.

In the room where these characters are gathered, a kakemono (painting) represents a box full of nuka into which nails have been driven.

III

Baka ni Tsukeru Kusuri wa Nai

There is no medicine that can cure a fool.

After trying everything, the mother of an absolutely idiotic child decides to consult a doctor. At the moment of his arrival the doctor finds the young child eating his meal. But instead of eating his rice like everyone else on the gozen (tray), he prefers to scoop it out of the tub with the paddle used to put rice in the guests’ cups.

The doctor tells the unfortunate mother that science is powerless in such a case.

IV

Niobo to Tatami wa Atarashi ga Yoi

It is better for the woman and the tatami to be new.

That is to say, it is preferable to change wives and mats from time to time.

The drawing explains the proverb literally. It shows a matchmaker leading a young girl to her new husband.

The bride is of low condition, her contribution modest.—The procession consists simply of a boy carrying a keg of sake, and a tatami maker who is going to redo the mats and who for this purpose carries on his shoulder the trestle used to repair them.

V

Amida no Kikari mo Kane Shidari

The rays of Buddha are proportionate to the gold offered to him.

A statue of Buddha receives gifts from wealthy people who make offerings aplenty: the god piles up the gold thrown to him and lovingly presses it under his arm. He lavishes his rays and favor on the rich supplicants. Husband and wife are showered with blessings.

While the god showers these individuals with favors, he pushes away with his other hand, with a contemptuous air, two miserable old men who have nothing to offer him but a bundle of coins and some pitiful change wrapped in paper.

Managing Director: A. Lahure

Actors of the late 18th century, by Shun-Yei and Toyokuni.

![]()

This work was published before January 1, 1930, and is in the public domain worldwide because the author died at least 100 years ago.

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse