Through China with a camera/Chapter 4

CHAPTER IV.

CANTON AND KWANG-TUNG PROVINCE

Tea—Foreign Hongs and Houses—Schroffing.

Distant view of Foreign Settlement, Canton.

The city of Canton stands on the north bank of the Chukiang or Pearl river, about ninety miles inland, and is accessible at all seasons to vessels of the largest tonnage. Communication between the capital and the other parts of the province is afforded by the three branches which feed the Pearl river, and by a network of canals and creeks. A line of fine steamers plies between the city and Hongkong, and the submarine telegraph at the latter place, has thus brought the once distant Cathay into daily correspondence with the western world. It is a pleasant trip from Hongkong up the broad Pearl river; from the deck of the steamers one may view with comfort the ruins of the Bogue forts, and think of the time and feelings of Captain Weddell, who in 1637 anchored the first fleet of English merchant vessels before them. The Chinese cabin in the Canton steamer is an interesting sight, too. It is crowded with passengers every trip; and there they lie on the deck in all imaginable attitudes, some on mats, smoking opium, others on benches, fast asleep. There are little gambling parties in one corner, and city merchants talking trade in another; and viewed from the cabin-door the whole presents a wonderfully confused perspective of naked limbs, arms and heads, queues, fans, pipes, and silk or cotton jackets. The owners of these miscellaneous effects never dream of walking about, or enjoying the scenery or sea-breeze. I only once noticed a party of Chinese passengers aroused to something bordering on excitement, and it was in this Canton steamer. They had caught a countryman in an attempt at robbery and determined to punish him in their own way. When the steamer reached the wharf, they relieved the delinquent of his clothing, bound it around his head, and tied his hands behind his back with cords: and in this condition sent him ashore to meet his friends, but not before they had covered his nakedness with a coat of paint of various tints.

My readers will remember the celebrated Governor Yeh of Canton, who was carried prisoner to Calcutta. He would almost be forgotten in this quarter were it not for a temple erected to his departed spirit. It may be seen on the bank of a suburban creek; a very pretty monument it is to remind one of our lively intercourse with the notorious Imperial commissioner in 1857, an intercourse marked by trouble and bloodshed throughout, and which ended in the capture of that unfortunate official in an obscure Yamen.

The Fatee gardens, so often described were still to be found, almost unchanged, at the side of a narrow creek on the right bank of the river. These gardens were nurseries for flowers, dwarf shrubs and trees. Like most Chinese gardens they covered only a small area, and were contrived to represent landscape gardening in miniature. Some distance below the Fatee creek, on the same side of the river, a number of Tea Hongs and tea-firing establishments are to be found. To these I now

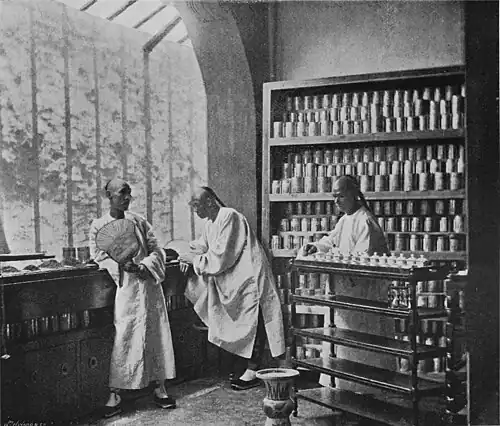

In a Chinese Tea-Hong, Canton.

The tea-trade in China is more or less a speculative one, always full of risks (as some of our merchants have found out to their cost); and though a vast amount of foreign capital is annually invested in the enterprise, it is probably only every second or third venture that will return, I do not say a handsome profit, but any profit at all.

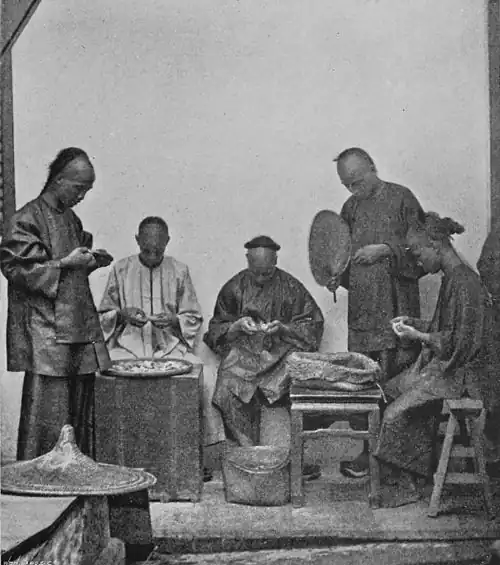

We will now proceed to another apartment and see the method adopted in the manufacture of gunpowder teas. First the fresh leaves of black tea are partially dried in the sun; these are next rolled, either in the palm of the hand, or on a flat tray, or by the feet in a hempen bag, then they are scorched in hollow iron pans over a charcoal fire, and after this are spread out on bamboo trays, that the broken stems and refuse may be picked out. In this large stone-paved room we notice the leaves in different stages of preparation. The

Chinese Tea Dealers.

Most of the tea shipped from Canton is now grown in the province of Kwang-tung; formerly part of it used to be brought from the "Tung-ting" district, but that now finds its way to Hankow. Leaves from the Taishan district are mostly used in making "Canton District Pekoe" and "Long-Leaf Scented Orange Pekoe," while Loting leaf makes "Scented Caper and Gunpowder" teas.

In order to see the foreign tea-tasters prosecuting a branch of science which they have made peculiarly their own, we must cross the river to Shameen, a pretty little green island, on which the foreign houses stand; looking with its villas, gardens and croquet-lawns and churches like the suburb of some English town. We ascend a flight of steps in a massive stone retaining wall with which Shameen is surrounded, — and this done we might wander for a whole day and examine all the houses on the island, without discovering a trace of a merchant's office, or any outward sign of commerce at all. Those who are familiar with the factory site, and who can figure what that must have been in olden times, when the foreign merchants were caged up like wild beasts and subjected to the company and taunts of the vilest part of the river population, and to the pestilential fumes of an open drain that carried the sewage of the city to the stream, will be surprised at the transformation that has, since those days, been wrought.

The present residences of foreigners on this grassy site (reclaimed mud flat, raised above the river) are substantial, elegant buildings of stone or brick, each surrounded by a wall; an ornamental railing, or bamboo hedge, enclosing the gardens and outhouses in its circuit. Except the firm's name on each small brass door-plate, there is nothing anywhere that tells us of trade. But when we have entered, we find the dwelling-house on the upper story, and the comprador's room and offices on the ground-floor; next to the offices the tea-taster's apartment. Ranged against the walls of this chamber are rows of polished shelves, covered with small round tin boxes of a uniform size, and each bearing a label and date in Chinese and English writing. These boxes contain samples of all the various sorts of old and new teas, used for reference and comparison in tasting, smelling and scrutinising parcels, or chops, which may

SUBURBAN RESIDENTS, CANTON.

The windows of the room have a northern aspect, and are screened off so as to admit only a steady skylight, which falls directly on a tea-board beneath. Upon this board the samples are spread on square wooden trays, and it is under the uniform light above described that the minute inspection of colour, make, general appearance and smell takes place. All these tests are made by assistants who have gone through a special course of training which fits them for the mysteries of their art. The knowledge which these experts possess is of the greatest importance to the merchant, as the profitable outcome of the crops selected for the home market depends, to a great extent, on their judgment and ability. It will thus be seen that the merchant, not only when he chooses his teas for exportation, but at the last moment before they are shipped, takes the minutest precautions against fraudulent shortcomings, either in quality or weight. It is possible, however, for a sound tea, if undercooked or imperfectly dried, to become putrid during the homeward voyage, and to reach this country in a condition quite unfit for use. This I know from my own experience. I at one time was presented with a box of tea by the Taotai of Taiwanfu, in Formosa, and when I first got it I found that some of the leaves had a slightly green tint and were damp. I had intended to bring this tea home to England; it was of good quality, but it spoiled before I left China. Judging from the quantities of tea that have been condemned, the importation of spurious cargoes can hardly be a lucrative trade.

Although Chinese commercial morality has not run to such a very low ebb as some might imagine, yet the clever traders of the lower orders of Cathay are by no means above resorting to highly questionable and ingenious practices of adulteration, when such practices can be managed with safety and profit. Thus the foreign merchant finds it always necessary to be vigilant in his scrutiny of tea, silk and other produce, before effecting a purchase. But equal care requires to be observed in all money transactions, as counterfeit coining is a profession carried on in Canton with marvellous success; so successful indeed, are the coiners of false dollars that the native experts, or schroffs, who are employed by foreign merchants (Mr. W. F. Mayers assured me), are taught the art of schroffing, or detecting counterfeit coin, by men who are in direct communication with the coiners of the spurious dollars in circulation.

In many of the Canton shops one notices the intimation "Schroffing taught here." This is a curious system of corruption, which one would think would be worth the serious attention of the Government. Were counterfeiting coining put down, there would be no need for the crafty instructors of schroffs; and at the same time the expensive staff of experts employed in banks and merchants' offices could be dispensed with.

But the dollar in the hands of a needy and ingenious Chinaman is not only delightful to behold, but it admits of a manipulation at once most skilful and profitable. The art of "schroffing" or detecting spurious coin and ascertaining the difference in the value of dollars of various issues, is studied as a profession by hundreds of young Chinamen, who find

SCHROFFING DOLLARS.