The Rocky Mountain Saints/Chapter 37

- EMIGRATING TO UTAH WITH HAND-CARTS.

- Mr. Chislett's Narrative

- The "Divine Plan" for emigrating the Poor

- Outfitting in Iowa City

- Organizing the Company

- Journey through Iowa

- The Elders prophesy a Successful Journey

- Brother Savage protests

- "Inspirational" Counsel followed

- The Carts break down

- Cattle are lost

- The Apostle Richards prophesies in the Name of the God of Israel

- The Elders eat the Fatted Calf

- Arrival at Fort Laramie

- Provisions become scarce

- Great Privations

- The People begin to faint by the Way

- Captain Willie's Bravery

- The Winter overtakes them

- Snow on the Mountains

- The Sweetwater

- Great Distress, Disease, and Death

- Envoys from Salt Lake Valley

- Provisions all gone

- Captain Willie goes in search of Aid

- Terrible Condition of the People

- Courage and Faithfulness of the Sufferers

- Arrival of Timely Aid

- A Thrilling Scene

- Hope revived

- "Too Late"

- Ravages of Death

- A Hard Road

- An Old Man's Death

- "Thirteen Corpses all Stiffly Frozen"

- Fifteen buried in One Grave

- The Ending of the Journey

- Great Kindness of the Elders and People of Utah

- The Pilgrims enter Zion

- Sixty-seven Emigrants dead on the Journey

- Greater Losses in another Company

- Folly of Modern Prophecies.

The story of the Hand-Cart Emigration to Utah that fills so melancholy a page in the history of the Mormon people could only be written properly by one who had himself passed through the sufferings which it relates. A gentleman now in Salt Lake City, and formerly a fellow-labourer with the Author in the Mormon missions, furnishes a graphic history equalling in interest the finest pages of fiction, yet strikingly true, and exhibiting a rare devotion that commands respect. He at first declined to affix his name, but the Author, persuaded of the value of his narrative, succeeded at last in inducing him to consent.

Mr. Chislett is a gentleman who enjoys the confidence and respect of those who know him, both in Europe and in the United States; and this episode of his life, illustrating as it does a phase of Mormon emigration, and exploding the presumptuous folly of the predictions of modern apostles, will be read with deep interest.

MR. CHISLETT'S NARRATIVE.

PART I.

THE PILGRIMS SET OUT FOR ZION.

"For several years previous to 1856, the poorer portion of the Mormon emigrants from Europe to Utah made the overland journey from 'the Frontiers' to Salt Lake City by ox-teams, under the management of the Church agents, who were generally elders returning to Utah after having performed missions in Europe or the Eastern States. The cost of the journey from Liverpool to Salt Lake by this method was from £10 to £12. All the emigrants who were obliged to travel in this manner were, if able, expected to walk all the way, or at least the greater part of the way. The teams were used for hauling provisions, and 100 lbs. of luggage were allowed to each emigrant. Old people, feeble women and children, generally could ride when they wished. The overland portion of the journey occupied from ten to twelve weeks.

"This was a safe method of emigration, and it added to the wealth of the new Territory by increasing its quota of live stock, wagons, and such articles of clothing, tools, etc., as the emigrants brought. These were all much needed in Utah in early days, and families going to the Territory with a surplus found good opportunities for exchanging them for land and the produce of the Valley. Many families came out with their own wagons; some of the more wealthy having several well laden with necessary articles. The growth and prosperity of the Territory were slow, gradual, and natural, and as each successive company of emigrants arrived they found the country prepared to receive them. Employment could generally be obtained by the mechanics (especially of the building trades) as soon as they arrived. The wealthy could find cultivated land at fair prices without having to endure the hardship of making new homes on unbroken land, while the agricultural labourer could always find a welcome among the farmers. Artisans and men of no trade were the only class who were really out of place. They had to begin life anew and strike out fresh pursuits, suffering frequently in the undertaking. But the general condition was prosperous.

"The growth of the colony was not, however, sufficiently rapid to suit the ambitious mind of Brigham Young. Thousands of faithful devotees of the Church were waiting patiently in Europe to join the new Zion of the West, but all their faith in Brigham was practically valueless. To be of any real benefit to the Church they must gather in Zion. The question was, how to transfer to Utah those who could not raise the necessary £10 sterling. The matter was discussed in the winter of 1855–6, in Salt Lake City, by Brigham and his chief men. After much debate their united wisdom devised and adopted a system of emigration across the plains by hand-carts, as being cheaper and consequently better under the circumstances for bringing the faithful poor from Europe.

"Whether Brigham was influenced in his desire to get the poor of Europe more rapidly to Utah by his sympathy with their condition, by his well-known love of power, his glory in numbers, or his love of wealth, which an increased amount of subservient labour would enable him to acquire, is best known to himself. But the sad results of his Hand-Cart scheme will call for a day of reckoning in the future which he cannot evade.

"Instructions were sent by Brigham and his chief men to their agent, Apostle F. D. Richards, at Liverpool, and were published by him in the Millennial Star with such a flourish of trumpets as would have done honour to any of the most momentous events in the world's history. That apostle announced to the Saints that God, ever watchful for the welfare of his people and anxious to remove them from the calamities impending over the wicked in Babylon, had inspired His servant Brigham with His spirit, and by such inspiration the hand-cart mode of emigration was adopted. By going to Zion in this way some difficulty would be experienced; but had not the Lord said that He would have a 'tried people,' and that they should come up 'through great tribulation,' etc. Thus reasoned this grave apostle—declaring the plan was God's own, and of His own devising through His servant Brigham. Thus the word went forth to the faithful Mormons with the stamp of Divinity upon it. They received it with gladness, believing in the assertion that 'He doeth all things well,' and they set about preparing for their journey—at least as many as could raise means to reach the frontiers. Those who had more money than was necessary for this were counselled to deposit all they had with F. D. Richards, that it might be used to help others to that point, as all who reached there would be surely sent through.

"Many, in their honest, simple whole-heartedness, and love for their brethren and sisters, obeyed this counsel, while many others helped their own immediate friends and acquaintances to emigrate. The result was that a greater number of the Saints left Liverpool for Utah that year than ever before or since. Of this, Richards felt proud, and frequently boasted of it, as though the success of the scheme was certain when the people had left Liverpool.

"What his instructions from Brigham were, or whether he exceeded them, it is immaterial now to enquire; but certain it is that the preparations on the frontiers were altogether inadequate to the number of emigrants, as indeed were the preparations throughout the entire journey west of New York. For instance, several hundred emigrants would arrive at Iowa City, expecting to find tents or some means of shelter, as agents had been sent on from Liverpool to purchase tents, hand-carts, wagons, and cattle, and to prepare generally for the coming flood of emigrants. But they were doomed to disappointment. There were no wagons or tents, and, for days after their arrival, no shelter but the broad heavens. They were delayed at Iowa City for some weeks—some of them for months—while carts were being made, and this, too, when they should have been well on their way.

"The 'Divine plan' being new in this country, of course hand-carts were not procurable, so they had to be made on the camp-ground. They were made in a hurry, some of them of very insufficiently seasoned timber, and strength was sacrificed to weight until the production was a fragile structure, with nothing to recommend it but lightness. They were generally made of two parallel hickory or oak sticks, about five feet long, and two by one and a half inches thick. These were connected by one cross-piece at one end to serve as a handle, and three or four similar pieces nearly a foot apart, commencing at the other end, to serve as the bed of the cart, under the centre of which was fastened a wooden axletree, without iron skeins. A pair of light wheels, devoid of iron, except a very light iron tire, completed the "divine" hand-cart. Its weight was somewhere near sixty pounds.

"When we arrived at Iowa City, the great out-fitting point for the emigration, we found that three hand-cart companies had already gone forward, under the respective captaincy of Edmund Ellsworth, Daniel McArthur, and Bunker, all Valley elders returning from missions to England. These companies reached Salt Lake City in safety before cold weather set in.[1] No carts being ready for us, nor indeed anything necessary for our journey, we were detained three weeks at Iowa Camp, where we could celebrate the Fourth of July.

"A few days after this we started on our journey, organized as follows: James G. Willie, captain of the company, which numbered about five hundred. Each hundred had a sub-captain, thus: first, Millen Atwood; second, Levi Savage; third, William Woodward; fourth, John Chislett; fifth, Ahmensen. The third hundred were principally Scotch; the fifth, Scandinavians. The other hundreds were mostly English. To each hundred there were five round tents, with twenty persons to a tent; twenty hand-carts, or one to every five persons; and one Chicago wagon, drawn by three yoke of oxen, to haul provisions and tents. Each person was limited to seventeen pounds of clothing and bedding, making eighty-five pounds of luggage to each cart. To this were added such cooking utensils as the little mess of five required. But their cuisine being scanty, not many articles were needed, and I presume the average would not exceed fifteen to twenty pounds, making in all a little over a hundred pounds on each cart. The carts being so poorly made, could not be laden heavily, even had the people been able to haul them.

"The strength of the company was equalized as much as possible by distributing the young men among the different families to help them. Several carts were drawn by young girls exclusively; and two tents were occupied by them and such females as had no male companions. The other tents were occupied by families and some young men; all ages and conditions being found in one tent. Having been thrown closely together on shipboard, all seemed to adapt themselves to this mode of tent-life without any marked repugnance.

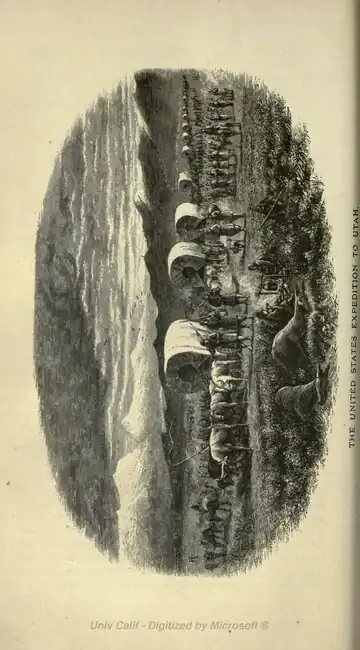

Image missingPassing through Iowa."As we travelled along, we presented a singular, and sometimes an affecting appearance. The young and strong went along gaily with their carts, but the old people and little children were to be seen straggling a long distance in the rear. Sometimes, when the little folks had walked as far as they could, their fathers would take them on their carts, and thus increase the load that was already becoming too heavy as the day advanced. But what will parents not do to benefit their children in time of trouble? The most affecting scene, however, was to see a mother carrying her child at the breast, mile after mile, until nearly exhausted. The heat was intense, and the dust suffocating, which rendered our daily journeys toilsome in the extreme.

"Our rations consisted of ten ounces of flour to each adult per day, and half that amount to children under eight years of age. Besides our flour we had occasionally a little rice, sugar, coffee, and bacon. But these items (especially the last) were so small and infrequent that they scarcely deserve mentioning. Any hearty man could eat his daily allowance for breakfast. In fact, some of our men did this, and then worked all day without dinner, and went to bed supperless or begged food at the farmhouses as we travelled along.

"The people in Iowa were very good in giving to those who asked food, expressing their sympathy for us whenever they visited our camp—which they did in large numbers if we stopped near a settlement. They tried to dissuade us from going to Salt Lake in that way, and offered us employment and homes among them. A few of our company left us from time to time; but the elders constantly warned us against 'the Gentiles,' and by close watching succeeded in keeping the company tolerably complete. Meetings were held nearly every evening for preaching, counsel, and prayer; the chief feature of the preaching being, 'obey your leaders in all things.'

"I do not know who settled the amount of our rations, but whoever it was, I should like him, or them, to drag a hand-cart through the State of Iowa in the month of July on exactly the same amount and quality of fare we had. This would be but simple justice. The Scripture says: 'Whatsoever measure ye mete shall be measured to you again.'

"When we travelled in this impoverished manner through Iowa, flour was selling at three cents per pound, and bacon seven to eight cents. The Church agents were, no doubt, short of money; but, where was the wisdom in sending forward so many people when the preparations were altogether inadequate for them? Would it not have been better to have brought over fewer emigrants with some small degree of comfort, than to have brought so many and have deprived them of the merest necessities of life?

"A little less than four weeks' travelling brought us to the Missouri river. We crossed it on a steam ferry-boat, and encamped at the town of Florence,[2] Nebraska, six miles above Omaha, where we remained about a week, making our final preparations for crossing the plains.

"The elders seemed to be divided in their judgment as to the practicability of our reaching Utah in safety at so late a season of the year, and the idea was entertained for a day or two of making our winter quarters on the Elkhorn, Wood river, or some eligible location in Nebraska; but it did not meet with general approval. A monster meeting was called to consult the people about it.

"The emigrants were entirely ignorant of the country and climate—simple, honest, eager to go to 'Zion' at once, and obedient as little children to the 'servants of God.' Under these circumstances it was natural that they should leave their destinies in the hands of the elders. There were but four men in our company who had been to the valley, viz.: Willie, Atwood, Savage, and Woodward; but there were several at Florence superintending the emigration, among whom elders G. D. Grant and W. H. Kimball occupied the most prominent position. These men all talked at the meeting just mentioned, and all, with one exception, favoured going on. They prophesied in the name of God that we should get through in safety. Were we not God's people, and would he not protect us? Even the elements he would arrange for our good, etc. But Levi Savage used his common sense and his knowledge of the country. He declared positively that to his certain knowledge we could not cross the mountains with a mixed company of aged people, women, and little children, so late in the, season without much suffering, sickness, and death. He therefore advised going into winter quarters without delay; but he was rebuked by the other elders for want of faith, one elder even declaring that he would guarantee to eat all the snow that fell on us between Florence and Salt Lake City. Savage was accordingly defeated, as the majority were against him. He then added: 'Brethren and sisters, what I have said I know to be true; but, seeing you are to go forward, I will go with you, will help you all I can, will work with you, will rest with you, will suffer with you, and, if necessary, I will die with you. May God in his mercy bless and preserve us. Amen.'

"Brother Savage was true to his word; no man worked harder than he to alleviate the suffering which he had foreseen, when he had to endure it. Oh, had the judgment of this one clear-headed man been heeded, what scenes of suffering, wretchedness, and death would have been prevented! But he was overwhelmed with the religious fanaticism and blind faith of others who thought the very elements would be changed or influenced to suit us, and that the seasons would be transposed for our accommodation because we, forsooth, were 'the people of God!'"

PART II.

THE JOURNEY ACROSS THE PLAINS.

"We started from Florence about the 18th of August, and travelled in the same way as through Iowa, except that our carts were more heavily laden, as our teams could not haul sufficient flour to last us to Utah; it was therefore decided to put one sack (ninety-eight pounds) on each cart in addition to the regular baggage. Some of the people grumbled at this, but the majority bore it without a murmur. Our flour ration was increased to a pound per day; fresh beef was issued occasionally, and each 'hundred' had three or four milch cows. The flour on the carts was used first, the weakest parties being the first relieved of their burdens.

"Everything seemed to be propitious, and we moved gaily forward full of hope and faith. At our camp each evening could be heard songs of joy, merry peals of laughter, and bon mots on our condition and prospects. Brother Savage's warning was forgotten in the mirthful ease of the hour. The only drawbacks to this part of our journey were the constant breaking down of carts and the delays caused by repairing them. The axles and boxes being of wood, and being ground out by the dust that found its way there in spite of our efforts to keep it out, together with the extra weight put on the carts, had the effect of breaking the axles at the shoulder. All kinds of expedients were resorted to as remedies for the rowing evil, but with variable success. Some wrapped their axles with leather obtained from boot-legs; others with tin, obtained by sacrificing tin-plates, kettles, or buckets from their mess outfit. Besides these inconveniences, there was felt a great lack of a proper lubricator. Of anything suitable for this purpose we had none at all. The poor folks had to use their bacon (already totally insufficient for their wants) to grease their axles, and some even used their soap, of which they had very little, to make their carts trundle somewhat easier. In about twenty days, however, the flour being consumed, breakdowns became less frequent, and we jogged along finely. We travelled from ten to twenty miles per day, averaging about fifteen miles. The people felt well, so did our cattle, and our immediate prospects of a prosperous journey were good. But the fates seemed to be against us.

"About this time we reached Wood river. The whole country was alive with buffaloes, and one night—or, rather, evening—our cattle stampeded. Men went in pursuit and collected what they supposed to be the herd; but, on corralling them for yoking next morning, thirty head were missing. We hunted for them three days in every direction, but did not find them. We at last reluctantly gave up the search, and prepared to travel without them as best we could. We had only about enough oxen left to put one yoke to each wagon; but, as they were each loaded with about three thousand pounds of flour, the teams could not of course move them. We then yoked up our beef cattle, milch cows, and, in fact, everything that could bear a yoke—even two-year old heifers. The stock was wild and could pull but little, and we were unable, with all our stock, to move our loads. As a last resort we again loaded a sack of flour on each cart.

"The patience and faith of the good honest people were shaken somewhat by this (to them) hard stroke of Providence. Some complained openly; others, less demonstrative, chewed the bitter cud of discontent; while the greater part saw the 'hand of the Lord' in it. The belief that we were the spiritual favourites of the Almighty, and that he would control everything for our good, soon revived us after our temporary despondency, and in a day or two faith was as assuring as ever with the pilgrims. But our progress was slow, the old breakdowns were constantly repeated, and some could not refrain from murmuring in spite of the general trustfulness. It was really hard for the folks to lose the use of their milch cows, have beef rations stopped, and haul one hundred pounds more on their carts. Every man and woman, however, worked to their utmost to put forward towards the goal of their hopes.

"One evening, as we were camped on the west bank of the North Bluff Fork of the Platte, a grand outfit of carriages and light wagons was driven into our camp from the East. Each vehicle was drawn by four horses or mules, and all the appointments seemed to be first rate. The occupants we soon found to be the apostle F. D. Richards, elders W. H. Kimball, G. D. Grant, Joseph A. Young, C. G. Webb, N. H. Felt, W. C. Dunbar, and others who were returning to Utah from missions abroad. They camped with us for the night, and in the morning a general meeting was called. Apostle Richards addressed us. He had been advised of the opposition brother Savage had made, and he rebuked him very severely in open meeting for his lack of faith in God. Richards gave us plenty of counsel to be faithful, prayerful, obediert to our leaders, etc., and wound up by prophesying in the name of Israel's God that 'though it might storm on our right and on our left, the Lord would keep open our way before us and we should get to Zion in safety.' This assurance had a telling effect on the people—to them it was 'the voice of God.' They gave a loud and hearty 'Amen,' while tears of joy ran down their sunburnt cheeks.

"These brethren told Captain Willie they wanted some fresh meat, and he had our fattest calf killed for them. I am ashamed for humanity's sake to say they took it. While we, four hundred in number, travelling so slowly and so far from home, with our mixed company of men, women, children, aged, sick, and infirm people, had no provisions to spare, had not enough for ourselves, in fact, these 'elders in Israel,' these 'servants of God,' took from us what we ourselves so greatly needed and went on in style with their splendid outfit, after preaching to us faith, patience, prayerfulness, and obedience to the priesthood. As they rolled out of our camp I could not, as I contrasted our positions and circumstances, help exclaiming to myself: 'Look on this picture, and on that!'

"We broke camp at once and turned towards the river, the apostle having advised us to go on to the south side. He and his company preceded us and waited on the opposite bank to indicate to us the best fording place. They stood and watched us wade the river—here almost a mile in width, and in places from two to three feet deep. Our women and girls waded, pulling their carts after them.

"The apostle promised to leave us provisions, bedding, etc., at Laramie if he could, and to secure us help from the valley as soon as possible.

"We reached Laramie about the 1st or 2d of September, but the provisions, etc., which we expected were not there for us. Captain Willie called a meeting to take into consideration our circumstances, condition, and prospects, and to see what could be done. It was ascertained that at our present rate of travel and consumption of flour, the latter would be exhausted when we were about three hundred and fifty miles from our destination! It was resolved to reduce our allowance from one pound to three-quarters of a pound per day, and at the same time to make every effort in our power to travel faster. We continued this rate of rations, from Laramie to Independence Rock.

"About this time Captain Willie received a letter from apostle Richards informing him that we might expect supplies to meet us from the valley by the time we reached South Pass. An examination of our stock of flour showed us that it would be gone before we reached that point. Our only alternative was to still further reduce our bill of fare. The issue of flour was then to average ten ounces per day to each person over ten years of age, and to be divided thus: working-men to receive twelve ounces, women and old men nine ounces, and children from four to eight ounces, according to age and size.

"This arrangement dissatisfied some, especially men with families; for so far they had really done better than single men, the children's rations being some help to them. But, taken altogether, it was as good a plan as we could have adopted under the circumstances.

"Many of our men showed signs of failing, and to reduce their rations below twelve ounces would have been suicidal to the company, seeing they had to stand guard at night, wade the streams repeatedly by day to get the women and children across, erect tents, and do many duties which women could not do.

"Our captain did his utmost to move us forward and always acted with great impartiality. The sub-captains had plenty of work, too, in seeing that rations were fairly divided, equally distributing the strength of their hundreds, helping the sick and the weakly, etc.

"We had not travelled far up the Sweetwater before the nights, which had gradually been getting colder since we left Laramie, became very. severe. The mountains before us, as we approached nearer to them, revealed themselves to view mantled nearly to their base in snow, and tokens of a coming storm were discernible in the clouds which each day seemed to lower around us. In our frequent crossings of the Sweetwater, we had really 'a hard road to travel.' The water was beautiful to the eye, as it rolled over its rocky bed as clear as crystal; but when we waded it time after time at each ford to get the carts, the women, and the children over, the beautiful stream, with its romantic surroundings (which should awaken holy and poetic feelings in the soul, and draw it nearer to the Great Author of life), lost to us its beauty, and the chill which it sent through our systems drove out from our minds all holy and devout aspirations, and left a void, a sadness, and—in some cases—doubts as to the justice of an overruling Providence.

"Our seventeen pounds of clothing and bedding was now altogether insufficient for our comfort. Nearly all suffered more or less at night from cold. Instead of getting up in the morning strong, refreshed, vigorous, and prepared for the hardships of another day of toil, the poor 'Saints' were, to be seen crawling out from their tents looking haggard, benumbed, and showing an utter lack of that vitality so necessary to our success.

"Cold weather, scarcity of food, lassitude and fatigue from over-exertion, soon produced their effects. Our old and infirm people began to droop, and they no sooner lost spirit and courage than death's stamp could be traced upon their features. Life went out as smoothly as a lamp ceases to burn when the oil is gone. At first the deaths occurred slowly and irregularly, but in a few days at more frequent intervals, until we soon thought it unusual to leave a camp-ground without burying one or more persons.

"Death was not long confined in its ravages to the old and infirm, but the young and naturally strong were among its victims. Men who were, so to speak, as strong as lions when we started on our journey, and who had been our best supports, were compelled to succumb to the grim monster. These men were worn down by hunger, scarcity of clothing and bedding, and too much labour in helping their families. Weakness and debility were accompanied by dysentery. This we could not stop or even alleviate, no proper medicines being in the camp; and in almost every instance it carried off the parties attacked. It was surprising to an unmarried man to witness the devotion of men to their families and to their faith, under these trying circumstances. Many a father pulled his cart, with his little children on it, until the day preceding his death. I have seen some pull their carts in the morning, give out during the day, and die before next morning. These people died with the calm faith and fortitude of martyrs. Their greatest regret seemed to be leaving their families behind them, and their bodies on the plains or mountains instead of being laid in the consecrated ground of Zion. The sorrow and mourning of the bereaved, as they saw their husbands and fathers rudely interred, were affecting in the extreme, and none but a heart of stone could repress a tear of sympathy at the sad spectacle.[3]

"Each death weakened our forces. In my hundred I could not raise enough men to pitch a tent when we encamped, and now it was that I had to exert myself to the utmost. I wonder I did not die, as many did who were stronger than I was. When we pitched our camp in the evening of each day, I had to lift the sick from the wagon and carry them to the fire, and in the morning carry them again on my back to the wagon. When any in my hundred died I had to inter them; often helping to dig the grave myself. In performing these sad offices I always offered up a heartfelt prayer to that God who beheld our sufferings, and begged him to avert destruction from us and send us help.

PART III.

FEARFUL SUFFERINGS: THE RAVAGES OF STARVATION, DISEASE, AND DEATH.

"We travelled on in misery and sorrow day after day. Sometimes we made a pretty good distance, but at other times we were only able to make a few miles' progress. Finally we were overtaken by a snow-storm which the shrill wind blew furiously about us. The snow fell several inches deep as we travelled along, but we dared not stop, for we had a sixteen-mile journey to make, and short of it we could not get wood and water.

"As we were resting for a short time at noon a light wagon was driven into our camp from the west. Its occupants were Joseph A. Young[4] and Stephen Taylor. They informed us that a train of supplies was on the way, and we might expect to meet it in a day or two. More welcome messengers never came from the courts of glory than these two young men were to us. They lost no time after encouraging us all they could to press forward, but sped on further east to convey their glad news to Edward Martin and the fifth hand-cart company who left Florence about two weeks after us, and who it was feared were even worse off than we were. As they went from our view, many a hearty 'God bless you' followed them.

"We pursued our journey with renewed hope and after untold toil and fatigue, doubling teams frequently, going back to fetch up the straggling carts, and encouraging those who had dropped by the way to a little more exertion in view of our soon-to-be improved condition, we finally, late at night, got all to camp—the wind howling frightfully and the snow eddying around us in fitful gusts. But we had found a good camp among the willows, and after warming and partially drying ourselves before good fires, we ate our scanty fare, paid our usual devotions to the Deity and retired to rest with hopes of coming aid.

"In the morning the snow was over a foot deep. Our cattle strayed widely during the storm, and some of them died. But what was worse to us than all this was the fact that five persons of both sexes lay in the cold embrace of death. The pitiless storm and the extra march of the previous day had been too much for their wasted energies, and they had passed through the dark valley to the bright world beyond. We buried these five people in one grave, wrapped only in the clothing and bedding in which they died. We had no materials with which to make coffins, and even if we had, we could not have spared time to make them, for it required all the efforts of the healthy few who remained to perform the ordinary camp duties and to look after the sick—the number of whom increased daily on our hands, notwithstanding so many were dying.

"The morning before the storm, or, rather, the morning of the day on which it came, we issued the last ration of flour. On this fatal morning, therefore, we had none to issue. We had, however, a barrel or two of hard bread which Captain Willie had procured at Fort Laramie in view of our destitution. This was equally and fairly divided among all the company. Two of our poor broken-down cattle were killed and their carcasses issued for beef. With this we were informed that we would have to subsist until the coming supplies reached us. All that now remained in our commissary were a few pounds each of sugar and dried apples, about a quarter of a sack of rice and a small quantity (possibly 20 or 25 lbs.) of hard bread. The brother who had been our commissary all the way from Liverpool had not latterly acted in a way to merit the confidence of the company; but it is hard to handle provisions and suffer hunger at the same time, so I will not write a word of condemnation. These few scanty supplies were on this memorable morning turned over to me by Captain Willie, with strict injunctions to distribute them only to the sick and to mothers for their hungry children, and even to them in as sparing a manner as possible. It was an unenviable place to occupy, a hard duty to perform; but I acted to the best of my ability, using all the discretion I could.

"Being surrounded by snow a foot deep, out of provisions, many of our people sick, and our cattle dying, it was decided that we should remain in our present camp until the supply-train reached us. It was also resolved in council that Captain Willie with one man should go in search of the supply-train and apprise its leader of our condition, and hasten him to our help. When this was done we settled down and made our camp as comfortable as we could. As Captain Willie and his companion left for the West, many a heart was lifted in prayer for their success and speedy return. They were absent three days—three days which I shall never forget. The scanty allowance of hard bread and poor beef, distributed as described, was mostly consumed the first day by the hungry, ravenous, famished souls.

"We killed more cattle and issued the meat; but, eating it without bread, did not satisfy hunger, and to those who were suffering from dysentery it did more harm than good. This terrible disease increased rapidly amongst us during these three days, and several died from exhaustion. Before we renewed our journey the camp became so offensive and filthy that words would fail to describe its condition, and even common decency forbids the attempt. Suffice it to say that all the disgusting scenes which the reader might imagine would certainly not equal the terrible reality. It was enough to make the heavens weep. The recollection of it unmans me even now-those three days! During that time I visited the sick, the widows whose husbands died in serving them, and the aged who could not help themselves, to know for myself where to dispense the few articles that had been placed in my charge for distribution. Such craving hunger I never saw before, and may God in his mercy spare me the sight again.

"As I was seen giving these things to the most needy, crowds of famished men and women surrounded me and begged for bread! Men whom I had known all the way from Liverpool, who had been true as steel in every stage of our journey, who in their homes in England and Scotland had never known want; men who by honest labour had sustained themselves and their families, and saved enough to cross the Atlantic and traverse the United States, whose hearts were cast in too great a mould to descend to a mean act or brook dishonour; such men as these came to me and begged bread. I felt humbled to the dust for my race and nation, and I hardly know which feeling was strongest at that time, pity for our condition, or malediction on the fates that so humbled the proud Anglo-Saxon nature. But duty might not be set aside by feeling, however natural, so I positively refused these men bread! But while I did so, I explained to them the painful position in which I was placed, and most of them acknowledged that I was right. Not a few of them afterwards spoke approvingly of my stern performance of duty. It is difficult, however, to reason with a hungry man; but these noble fellows, when they comprehended my position, had faith in my honour. Some of them are in Utah to-day, and when we meet, the strong grip of friendship overcomes, for the moment at least, all differences of opinion which we may entertain on any subject.[5] May the Heavens ever be kind to them, whatever their faith, for they are good men and true. And the sisters who suffered with us—may the loving angels ever be near them to guard them from the ills of life.

Image missing"Came to me and begged Bread.""The storm which we encountered, our brethren from the Valley also met, and, not knowing that we were so utterly destitute, they encamped to await fine weather. But when Captain Willie found them and explained our real condition, they at once hitched up their teams and made all speed to come to our rescue. On the evening of the third day after Captain Willie's departure, just as the sun was sinking beautifully behind the distant hills, on an eminence immediately west of our camp several covered wagons, each drawn by four horses, were seen coming towards us. The news ran through the camp like wildfire, and all who were able to leave their beds turned out en masse to see them. A few minutes brought them sufficiently near to reveal our faithful captain slightly in advance of the train. Shouts of joy rent the air; strong men wept till tears ran freely down their furrowed and sun-burnt cheeks, and little children partook of the joy which some of them hardly understood, and fairly danced around with gladness. Restraint was set aside in the general rejoicing, and as the brethren entered our camp the sisters fell upon them and deluged them with kisses. The brethren were so overcome that they could not for some time utter a word, but in choking silenced repressed all demonstration of those emotions that evidently mastered them. Soon, however, feeling was somewhat abated, and such a shaking of hands, such words of welcome, and such invocation of God's blessing have seldom been witnessed.

"I was installed as regular commissary to the camp. The brethren turned over to me flour, potatoes, onions, and a limited supply of warm clothing for both sexes, besides quilts, blankets, buffalo-robes, woollen socks, etc. I first distributed the necessary provisions, and after supper divided the clothing, bedding, etc., where it was most needed. That evening, for the first time in quite a period, the songs of Zion were to be heard in the camp, and peals of laughter issued from the little knots of people as they chatted around the fires. The change seemed almost miraculous, so sudden was it from grave to gay, from sorrow to gladness, from mourning to rejoicing. With the cravings of hunger satisfied, and with hearts filled with gratitude to God and our good brethren, we all united in prayer, and then retired to rest.

"Among the brethren who came to our succour were elders W. H. Kimball and G. D. Grant. They had remained but a few days in the Valley before starting back to meet us. May God ever bless them for their generous, unselfish kindness and their manly fortitude! They felt that they had, in a great measure, contributed to our sad position; but how nobly, how faithfully, how bravely they worked to bring us safely to the Valley—to the Zion of our hopes!"

PART IV.

THE PILGRIMS ENTER THE CITY OF THE SAINTS.

"The next morning the small company which came to our relief divided: : one half, under G. D. Grant, going east to meet Martin's company, and the other half, under W. H. Kimball, remaining with us. From this point until we reached the Valley, W. H. Kimball took full charge of us. "We travelled but a few miles the first day, the roads being very heavy. All who were unable to pull their carts were allowed to put their little outfits into the wagon and walk along, and those who were really unable to walk were allowed to ride. The second day we travelled a little farther, and each day Brother Kimball got the company along as far as it was possible to move it, but still our progress was very slow.

"Timely and good beyond estimate as the help which we received from the Valley was to our company generally, it was too late for some of our number. They were already prostrated and beyond all human help. Some seemed to have lost mental as well as physical energy. We talked to them of our improved condition, appealed to their love of life and showed them how easy it was to retain that life by arousing themselves; but all to no purpose. We then addressed ourselves to their religious feelings, their wish to see Zion; to know the Prophet Brigham; showed them the good things that he had sent out to us, and told them how deeply he sympathized with us in our sufferings, and what a welcome he would give us when we reached the city. But all our efforts were unavailing; they had lost all love of life, all sense of surrounding things, and had sunk down into a state of indescribable apathy.

"The weather grew colder each day, and many got their feet so badly frozen that they could not walk, and had to be lifted from place to place. Some got their fingers frozen; others their ears; and one woman lost her sight by the frost. These severities of the weather also increased our number of deaths, so that we buried several each day.

"A few days of bright freezing weather were succeeded by another snow-storm. The day we crossed the Rocky Ridge it was snowing a little—the wind hard from the north-west—and blowing so keenly that it almost pierced us through. We had to wrap ourselves closely in blankets, quilts, or whatever else we could get, to keep from freezing. Captain Willie still attended to the details of the company's travelling, and this day he appointed me to bring up the rear. My duty was to stay behind everything and see that nobody was left along the road. I had to bury a man who had died in my hundred, and I finished doing so after the company had started. In about half an hour I set out on foot alone to do my duty as rear-guard to the camp. The ascent of the ridge commenced soon after leaving camp, and I had not gone far up it before I overtook a cart that the folks could not pull through the snow, here about knee-deep. I helped them along, and we soon overtook another. By all hands getting to one cart we could travel; so we moved one of the carts a few rods, and then went back and brought up the other. After moving in this way for a while, we overtook other carts at different points of the hill, until we had six carts, not one of which could be moved by the parties owning it. I put our collective strength to three carts at a time, took them a short distance, and then brought up the other three. Thus by travelling over the hill three times—twice forward and once back—I succeeded after hours of toil in bringing my little company to the summit. The six carts were then trotted on gaily down hill, the intense cold stirring us to action. One or two parties who were with these carts gave up entirely, and but for the fact that we overtook one of our oxteams that had been detained on the road, they must have perished on that Rocky Ridge. One old man, named James (a farm-labourer from Gloucestershire), who had a large family, and who had worked very hard all the way, I found sitting by the roadside unable to pull his cart any farther. I could not get him into the wagon, as it was already overcrowded. He had a shot-gun which he had brought from England, and which had been a great blessing to him and his family, for he was a good shot, and often had a mess of sage hens or rabbits for his family. I took the gun from the cart, put a small bundle on the end of it, placed it on his shoulder, and started him out with his little boy, twelve years old. His wife and two daughters older than the boy took the cart along finely after reaching the summit.

"We travelled along with the ox-team and overtook others, all so laden with the sick and helpless that they moved very slowly. The oxen had almost given out. Some of our folks with carts went ahead of the teams, for where the roads were good they could out-travel oxen; but we constantly overtook some stragglers, some with carts, some without, who had been unable to keep pace with the body of the company. We struggled along in this weary way until after dark, and by this time our 'rear' numbered three wagons, eight hand-carts, and nearly forty persons. With the wagons were Millen Atwood, Levi Savage, and William Woodward, captains of hundreds, faithful men who had worked hard all the way.

"We finally came to a stream of water which was frozen over. We could not see where the company had crossed. If at the point where we struck the creek, then it had frozen over since we passed it. We started one team to cross, but the oxen broke through the ice and would not go over. No amount of shouting and whipping could induce them to stir an inch. We were afraid to try the other teams, for even should they cross we could not leave the one in the creek and go on. There was no wood in the vicinity, so we could make no fire, and were uncertain what to do. We did not know the distance to the camp, but supposed it to be three or four miles. After consulting about it, we resolved that some one should go on foot to the camp to inform the captain of our situation. I was selected to perform the duty, and I set out with all speed. In crossing the creek I slipped through the ice and got my feet wet, my boots being nearly worn out. I had not gone far when I saw some one sitting by the roadside. I stopped to see who it was, and discovered the old man James and his little boy. The poor old man was quite worn out.

"I got him to his feet and had him lean on me, and he walked a little distance, but not very far. I partly dragged, partly carried him a short distance farther, but he was quite helpless, and my strength failed me. Being obliged to leave him to go forward on my own errand, I put down a quilt I had wrapped round me, rolled him in it, and told the little boy to walk up and down by his father, and on no account to sit down, or he would be frozen to death. I told him to watch for teams that would come back, and to hail them when they came. This done I again set out for the camp, running nearly all the way and frequently falling down, for there were many obstructions and holes in the road. My boots were frozen stiff, so that I had not the free use of my feet, and it was only by rapid motion that I kept them from being badly frozen. As it was, both were nipped.

"After some time I came in sight of the camp fires, which encouraged me. As I neared the camp I frequently overtook stragglers on foot, all pressing forward slowly. I stopped to speak to each one, cautioning them all against resting, as they would surely freeze to death. Finally, about 11 P. M., I reached the camp almost exhausted. I had exerted myself very much during the day in bringing the rear carts up the ridge, and had not eaten anything since breakfast. I reported to Captains Willie and Kimball the situation of the folks behind. They immediately got up some horses, and the boys from the Valley started back about midnight to help the ox-teams in. The night was very severe and many of the emigrants were frozen. It was 5 A. M. before the last team reached the camp.

"I told my companions about the old man James and his little boy. They found the little fellow keeping faithful watch over his father, who Image missingThe Old Man James. lay sleeping in my quilt just as I left him. They lifted him into a wagon, still alive, but in a sort of stupor. He died before morning. His last words were an enquiry as to the safety of his shot-gun.

"There were so many dead and dying that it was decided to lie by for the day. In the forenoon I was appointed to go round the camp and collect the dead. I took with me two young men to assist me in the sad task, and we collected together, of all ages and both sexes, thirteen corpses, all stiffly frozen. We had a large square hole dug in which we buried these thirteen people, three or four abreast and three deep. When they did not fit in, we put one or two crosswise at the head or feet of the others. We covered them with willows and then with the earth. When we buried these thirteen people some of their relatives refused to attend the services. They manifested an utter indifference about it. The numbness and cold in their physical natures seem to have reached the soul, and to have crushed out natural feeling and affection. Had I not myself witnessed it, I could not have believed that suffering would have produced such terrible results. But so it was. Two others died during the day, and we buried them in one grave, making fifteen in all buried on that camp ground. It was on Willow creek, a tributary of the Sweetwater river. I learned afterwards from men who passed that way the next summer, that the wolves had exhumed the bodies, and their bones were scattered thickly around the vicinity.

"What a terrible fate for poor, honest, God-fearing people, whose greatest sin was believing with a faith too simple that God would for their benefit reverse the order of nature. They believed this because their elders told them so; and had not the apostle Richards prophesied in the name of Israel's God that it would be so? But the terrible realities proved that Levi Savage, with his plain common sense and statement of facts, was right, and that Richards and the other elders, with the 'Spirit of the Lord,' were wrong.

"The day of rest did the company good, and we started out next morning with new life. During the day we crossed the Sweetwater on the ice, which did not break, although our wagons were laden with sick people. The effects of our lack of food, and the terrible ordeal of the Rocky Ridge, still remained among us. Two or three died every day. At night we camped a little east by north from the South Pass, and two men in my hundred died. It devolved on me to bury them. This I did before breakfast. The effluvia from these corpses were horrible, and it is small matter for wonder that after performing the last sad offices for them I was taken sick and vomited fearfully. Many said my 'time' had come, and I was myself afraid that such was the case, but by the blessing of God I got over it and lived.

"It had been a practice among us latterly, when a person died with any good clothes on, to take them off and distribute them among the poor and needy. One of the men I buried near South Pass had on a pair of medium-heavy laced shoes. I looked at them and at my own worn-out boots. I wanted them badly, but could not bring my mind to the 'sticking-point' to appropriate them. I called Captain Kimball up and showed him both, and asked his advice. He told me to take them by all means, and tersely remarked: 'They will do you more good than they will him.' I took them, and but for that would have reached the city of Salt Lake barefoot.

"Near South Pass we found more brethren from the Valley, with several quarters of good fat beef hanging frozen on the limbs of the trees where they were encamped. These quarters of beef were to us the handsomest pictures we ever saw. The statues of Michael Angelo, or the paintings of the ancient masters, would have been to us nothing in comparison to these life-giving pictures.

"After getting over the Pass we soon experienced the influence of a warmer climate, and for a few days we made good progress. Image missing"What of the Promises?" We constantly met teams from the Valley, with all necessary provisions. Most of these went on to Martin's company, but enough remained with us for our actual wants. At Fort Bridger we found a great many teams that had come to our help. The noble fellows who came to our assistance invariably received us joyfully, and did all in their power to alleviate our sufferings. May they never need similar relief! From Bridger all our company rode, and this day I also rode for the first time on our journey. The entire distance from Iowa City to Fort Bridger I walked, and waded every stream from the Missouri to that point, except Elkhorn, which we ferried, and Green river, which I crossed in a wagon. During the journey from Bridger to Salt Lake a few died of dysentery, and some from the effects of frost the day we crossed the fatal Rocky Ridge. But those who weathered that fatal day and night, and were free from disease, gradually regained strength and reached Salt Lake City in good health and spirits.

"When we left Iowa City we numbered about five hundred persons. Some few deserted us while passing through Iowa, and some remained at Florence. When we left the latter place we numbered four hundred and twenty, about twenty of whom were independent emigrants with their own wagons, so that our hand-cart company was actually four hundred of this number. Sixty-seven died on the journey, making a mortality of one-sixth of our number. Of those who were sick on our arrival, two or three soon died. President Young had arranged with the bishops of the different wards and settlements to take care of the poor emigrants who had no friends to receive them, and their kindness in this respect cannot be too highly praised. It was enough that a poor family had come with the hand-carts, to insure help during the winter from the good brethren in the different settlements. My old friend W. G. Mills and his wife received me and my betrothed most kindly, so I had no need of Church aid.

"After arriving in the Valley, I found that President Young, on learning, from the brethren who passed us on the road, of the lateness of our leaving the frontier, set to work at once to send us relief. It was the October Conference when they arrived with the news. Brigham at once suspended all conference business, and declared that nothing further should be done until every available team was started out to meet us. He set the example by sending several of his best mule teams laden with provisions. Heber Kimball did the same, and hundreds of others followed their noble example. People who had come from distant parts of the Territory to attend conference volunteered to go out to meet us, and went at once. The people who had no teams gave freely of provisions, bedding, etc.—all doing their best to help us.

"We arrived in Salt Lake City on the 9th of November, but Martin's company did not arrive until about the 1st of December. They numbered near six hundred on starting, and lost over one-fourth of their number by death. The storm which overtook us while making the sixteen-mile drive on Sweetwater, reached them at North Platte. There they settled down to await help or die, being unable to go any farther. Their camp-ground became indeed a veritable grave-yard before they left it, and their dead lie even now scattered along from that point to Salt Lake. They were longer without food than we were, and being more exposed to the severe weather their mortality was, of course, greater in proportion.

"Our tale is their tale partly told; the same causes operated in both cases, and the same effects followed.

"Immediately that the condition of the suffering emigrants was known in Salt Lake City, the most fervent prayers for their deliverance were offered up. There, and throughout the Territory, the same was done as soon as the news reached the people. Prayers in the Tabernacle, in the Image missingJohn Chislett. school-house, in the family circle, and in the private prayer circles of the priesthood were constantly offered up to the Almighty, begging Him to avert the storm from us. Such intercessions were invariably made on behalf of Martin's company, at all the meetings which I attended after my arrival. But these prayers availed nothing more than did the prophecies of Richards and the elders. It was the stout hearts and strong hands of the noble fellows who came to our relief, the good teams, the flour, beef, potatoes, the warm clothing and bedding, and not prayers nor prophecies, that saved us from death. It is a fact patent to all the old settlers in Utah, that the fall storms of 1856 were earlier and more severe than were ever known before or since. Instead of their prophecies being fulfilled and their prayers answered, it would almost seem that the elements were unusually severe that season, as a rebuke to their presumption."

THE STORY OF MARTIN'S COMPANY. TERRIBLE SUFFERING AND PRIVATION

Mr. Chislett's thrilling narrative should properly have been supplemented by a relation of the sad experience of the last hand-cart company, under the guidance of elder Martin. The story already told is too deeply interesting to allow the listener to leave the last company struggling with the winter's fury, without a feeling of sympathy, and a very natural desire to know the fate of the poor emigrants. It could not be expected that elder Martin himself would furnish such a history, as its authorship would have cost him his membership in the Church. A gentleman, however, in the ox-train that followed the last of the hand-carts, and closed that year's emigration to Zion, and who was himself an eye-witness and sufferer, has furnished the Author with the following picture of endurance, sacrifice, and heroism that fitly closes the story of the "experiment"[6] of the divine plan for gathering the poor from Europe:

"Iowa City was selected that year for an outfitting point for Salt Lake Valley—the haven of rest for the travel-tired Saints. The apostle John Taylor had charge of the emigration in New York, the apostle Erastus Snow at St. Louis, the apostle Franklin D. Richards in Liverpool, and elder Daniel Spencer at Iowa City. There was some trouble among them as to who was chief, which occasioned much delay, and was probably never settled. To this difference are attributable the suffering and death of so many persons which occurred later in the season.

"Elder Chauncey G. Webb bought the wagons—the first of the Chicago make that subsequently became so popular in Utah—and also the material for making hand-carts, and shipped them to Iowa City, to which point the railroad had just been completed. The artisans were selected from among the emigrants, and were required to work without wages, and this they did faithfully if not cheerfully. While thus working they were insufficiently rationed, which caused great dissatisfaction, resulting in a refusal to continue their labours unless they were properly supplied. Their demand was complied with.

"The hand-carts were fitted up on the most economical plan, and so far was parsimony carried that the wheels had no tires, and to preserve the felloes the emigrants wound them with raw-hide while en route. This defect was afterwards partially remedied by putting on a rim of hoop-iron and rivetting where it lapped. Elder John Van Cott was deputed to buy and bring up cattle and mules, which he did, I believe, from Missouri. The trouble before named as to who was the "big chief" occasioned delays in branches of the outfitting, so that company after company arrived on the camping-ground, and had to stay there a long time before they could commence their journey, but I cannot say how long.

"When the cattle arrived they were entrusted to the hand-cart emigrants to herd, and this part of the business was very badly managed. The hand-cart folks had no interest whatever in the oxen, besides which they were new to the business, and were inefficiently directed. The consequence was that lot after lot of the stock was lost, and a proportionately greater price was put on what was left to cover the deficiency, the good Saints being forbidden to buy from settlers. The independent companies wanted to purchase their own stock, with the privilege of taking care of it themselves, but this was not allowed. From the above causes the cattle 'increased in value'—I think, three times—and were finally delivered to the emigrants at much higher prices than they could have been bought for in the neighbourhood. In this way the independent companies were kept back in order that they with their teams might relieve the handcarts, if needed.

"I will say nothing about the percentage collected from the emigrants on passage, railroad, wagons, hand-carts, and provisions-it is perhaps unnecessary.

"Florence, some six miles above Omaha, was chosen as a final outfitting depot for the Great Plains, and pulling the hand-carts from Iowa City to the Missouri river demonstrated the weak places both in carts and men. On arrival there they were without delay outfitted for their long journey, supplies having been sent up in quantity from St. Louis. James McGaw was in charge at Florence; he was a capable and indefatigable man.

"The last hand-cart train, under Tyler and Martin, arrived at Florence towards the middle of August, and many of the people were discouraged at the prospect ahead, but they were cheered by the elders preaching and telling them that a testimony would be given them that they were the chosen people of God, for they would go through safe and unharmed. 'The Indians, the seasons, nay, the very elements, would be controlled for their benefit, and after they got through they would hear of storms on the right and on the left, of which they in their travelling would know nothing.' Notwithstanding this encouragement, some remained behind for that season-and for many seasons, for aught I know; others begged hard for permission to do so, but this was refused; others offered their personal effects and promises to pay after arrival in Utah to any one who would take them in wagons. One lady offered all her jewellery, worth a considerable sum, for that purpose.

"The last ox-team—of which John A. Hunt had charge—was de- spatched soon after. It was a sort of Church train; that is, it consisted of wagons belonging to the returning missionaries, viz., Daniel Spencer, C. H. Wheelock, C. G. Webb, Captain Dan. Jones, F. D. Richards, James Linforth, and others. The wool or cotton machinery brought by George Halliday was in this train, and also the harp belonging to the poor old blind man Giles, which, as he was unable to pay freight upon it, he had 'donated' to Brigham Young. He was afterwards accorded the privilege of going to Brigham Young's mansion and playing upon his own instrument sometimes, of which privilege he gladly availed himself. It is said that the poor, afflicted old man would play there for hours at a time, while the hot tears streamed down his face as thoughts that would not be controlled rose unbidden in his mind. He afterwards got possession of his much loved instrument: he may have bought it or Brigham Young may have given it to him, as no one of his household could play on it then.

Image missingCrossing the Platte River.In this last train there were also several young girls; some of whom had a wagon fitted up for their comfort, and others had still better accommodation in the way of ambulance or carriage. The wagons belonging to Mr. Tenant—whose property soon melted away in Zion—were also in this train. Mr. Tenant died on the plains at O'Fallon's Bluffs. Mr. Hunt had instructions on no account to pass Tyler's hand-cart train-a pretty conclusive proof that what the elders had told the Saints with so much earnestness about the Heavens protecting them against the storms was an assurance they did not themselves believe.

"The wagons overtook the hand-carts at the Platte crossing, west, I think, of Laramie, and the poor hand-cart folks were thoroughly worn out and weak alike in body and mind. Under all circumstances they were regularly called up to prayers, and it was remarked that the shorter the rations the longer were the prayers. At this time great numbers of the emigrants died. I do not know how many, and will not attempt to conjecture, for a general account is sufficiently painful without particularizing. The wagon and hand-cart train camped together at the crossing of the river—and such a crossing! The men from the ox-train made each several trips across the Platte, sometimes pulling a hand-cart, and sometimes carrying on their backs a sick or weak man, woman, or child. Then, after all were over, there followed more long prayers and lengthened exhortations, to which the poor emigrants listened in their wet clothes and shivering with the cold. These prayers were succeeded by the distribution of their scanty rations.

"Next morning one of the men was found close to camp, dead and partly eaten by the wolves. He had gone out and was perhaps too tired or too careless of life, or possibly was unable to return. It was at this place that Tyler, when asked to lend his riding mule for the purpose of helping to take the sick and the aged men and women across, refused, assigning as a reason that he did not want his mules worn out. The mortality at this camp was greater than usual.

"The first snow which overtook the emigrants was on the east side of the river at the last Platte crossing, about sixty or seventy miles below Devil's Gate, near Red Buttes. Several trappers and traders lived there, among whom were Reichau, Seminole, Baptiste, Pappau, and others. The river was forded and camp made some two or three miles up on the other side. Here there was a very heavy snow-storm, and the train was unable to move at all. It was at this camp that Joseph A. Young and Steve Taylor met the disheartened emigrants and infused into them new energy. The grass was covered with snow, and cottonwood trees were cut down so that the cattle might feed upon the bark and small branches.

"The toilsome march was again renewed under increased difficulties, and when we had advanced as far as Sage creek we met some more of the returned missionaries sent out by Brigham Young at the October conference to help the people through the difficulties caused by the foolish and fatal delay at the starting-point. C. H. Wheelock and John Van Cott were among this relief party. Too much praise cannot be given to those who thus came out from Salt Lake to help us: they worked like heroes, and their moral influence accomplished perhaps as much as their bodily efforts, for they were full of stamina, while the emigrants were utterly worn out.

"The toilsome march was immediately resumed, and to give you an idea of how low the oxen were, I may mention the fact that the pulling of the wagons up Prospect Hill killed several of them—perhaps fifteen.

"On arrival at Devil's Gate on the Sweetwater, where we found five or six log-houses in a dilapidated condition, it was concluded that the handcarts should go no farther. A temporary halt was therefore made, and a remodelling of both trains was made. The wagons were unloaded and the contents stored in two of the log-houses; the hand-carts were unloaded and the people were put into the wagons, as many being placed in each wagon as the teams could move, and the remainder were left. Assistance was constantly arriving from Salt Lake, and those fresh teams helped wonderfully.

"The weather now set in so cold that in two days the Sweetwater river was frozen thick enough to bear the wagons and teams, and they crossed on the ice. Several more people died and were buried at Devil's Gate. Twenty men were detailed to remain there all winter to take care of the property left, and also a lot of young stock that was too poor to drive through at that time. D. W. Jones, Ben. Hampton, and F. M. Alexander—three men from Salt Lake—were appointed to this charge; the other seventeen were emigrants. A small quantity of flour was left with them some five or six sacks, I should think—and the rest of the people moved on.

"The track of the emigrants was marked by graves, and many of the living suffered almost worse than death. One sick man there, who was holding by the wagon-bars to save himself from the jolting, had all his fingers frozen off. Men may be seen to-day in Salt Lake City, who were boys then, hobbling round on their club-feet, all their toes having been frozen off in that fearful march.

"It is a noticeable fact that, as a rule, the men failed first: the poor fellows toiled on until they could do so no longer. They have been accused of a lack of consideration, and of being devoid of all manhood, to let women and girls slave as they did. It is true that a fearful amount of selfishness, not to say brutality, was brought to the surface; but perhaps the above few words of explanation may serve to temper the opinion which might otherwise have been formed respecting the conduct of some of them. It may possibly be said that the men should have worked until they died on their tracks, rather than see wives and mothers engage in that terrible toil. Some certainly did so, and for those who did not, it may be urged that humanity is frail at best, and that hunger and hard work, endured hundreds of miles from any hope of relief in the full bitterness of a most inclement season, not only destroy all romance but deaden the natural feelings of the most manly and affectionate.

"What remained of the last hand-cart and ox-train companies for that season were got into Salt Lake by the exercise of almost superhuman exertions, and numbers died after their arrival.

"The twenty left at the Devil's Gate were at once put on rations of flour, but of meat they had enough, such as it was. The weather was intensely cold; the snow fell deep, and the wolves soon began to make sad havoc among the poor stock, and what the wolves spared the season threatened to kill. The remainder was therefore driven up, killed, and the meat frozen. A United States mail came up from the East, but could take their mud wagons no further, so the men left them and started again with packed mules, but they could not travel, and returned to the Platte Bridge. This I mention to show that no provisions could reach the Devil's Gate.

"The flour was soon consumed, and meat without salt was the only article of food, and even that began to run short. About this time Jones and another man took the only two horses that were left—all the rest had died—and started for Platte Bridge to try and obtain some supplies. The first night out the wolves killed one horse, and the other was not seen until spring; so they returned empty-handed and on foot. There was very little game, and only a buffalo, a deer, and a few rabbits were shot. Finally the meat was consumed; then the hides were eaten, as also all the hide wrapped round the wheels of the hand-carts, and every scrap about the wagons and the neck-piece of the buffalo-skin, which had already done service as a doormat for two months. In the spring they subsisted on thistle roots, segoes, and a species of wild garlic, until flour came down from Salt Lake. But, to cut a long story short, the twenty men eventually got safely through; terribly emaciated it is true, but still safely.

"Such was the ending of the 'divine plan' for emigrating the poor in the year 1856."

The story of the hand-cart expedition has now been partially told, and that for the first time, to the public, for no pen can ever fully trace nor pencil picture the sufferings of that poor, devoted people. It would melt the hardest heart to listen to the personal recitals of that horrible journey which in moments of confidence the sufferers relate to their friends. One of the elders, whose pen was the most potent in England in urging the poor to emigrate by hand-carts, and who in the honest sincerity of his faith confided implicitly in the inspiration of apostles and prophets, was destined to witness and share in the deepest of that suffering. Of the intensity of the cold which the last company endured, his story is almost incredible. Men and women sitting on a wagon-tongue, on the ground, or leaning against their fragile carts while eating their scanty fare would in an instant die without an evidence of coming change. With a morsel of bread or biscuit in their hands, nearing it to their mouths, could be seen men, halelooking and apparently strong, stiff in death. Such scenes can hardly be imagined by those who did not witness them, but to the hundreds of men and women who had fled from "merry England" to escape the destruction which they were taught was coming upon the Gentile nations, what a commentary was there upon the predictions of men who claimed to be the inspired servants of the most high God, in that bitter struggle for life.

But the reader will justly inquire—What was the sequel to the hand-cart story, and how was it understood in Utah?

When the news reached Brigham Young, as already stated, he did all that man could do to save the remnant and relieve the sufferers. Never in his whole career did he shine so gloriously in the eyes of the people. There was nothing spared that he could contribute or command. In the Tabernacle he was "the Lion of the Lord," and "his fierce anger was kindled" against those whom he supposed were the cause of the calamity.

The apostle Richards was at once chosen as the victim of his wrath, and upon him and his counsellor, elder Daniel Spencer, he spent the fury of his soul. When Brigham is aroused he thinks of nothing but the annihilation of his enemy. A more humble, devoted worshipper of Brigham never breathed than the apostle Richards had been; at Brigham's word he would have licked the dust of his feet, and to carry out the purposes of his prophet he would have travelled to the ends of the earth, or would have joyfully given his life to shield him from harm. By nature F. D. Richards is a kind, good man, with more love and devotion than are good for him, and it was in his pride to make Brigham great in carrying out the "divine plan" that he had aroused the poor Mormons in Europe to emigrate in greater numbers than he had at last the capacity to control and direct. He counted upon the aid of a brother apostle—John Taylor—then at New York, which he appears not to have received in the way that he expected, and, that failing him, the doom of the hand-cart scheme became a certainty.

Blinded, it is charged, by pride and selfishness, neither of these apostles foresaw the distant results of this misunderstanding, or neither of them would have risked the consequences; but there was a valuable lesson in store for both, and still more important instruction for the Mormons.

The agency of the Mormon emigration at that time was a very profitable appointment. With this department attached to the Liverpool publishing office, the presidency of the British mission was always coveted by the apostles. It afforded many "opportunities"[7] of replenishing the family purse.

By arrangement with ship-brokers at Liverpool, a commission of half a guinea per head was allowed the agent for every adult emigrant that he sent across the Atlantic, and the railroad companies in New York allowed a percentage on every emigrant ticket, and some abatement was also made on the freight of extra baggage in favour of the agent. But a still larger revenue was derived from the outfitting on the frontiers. The agents purchased all the cattle, wagons, tents, wagon-covers, flour, cooking utensils, stoves, and the staple articles for a three months' journey across the plains, and from them the Saints supplied themselves. Many a good editorial was writ-. ten and sermon preached upon the blessings of unity and accumulative purchases, and "no one could be regarded as in good standing in the Church" who would sail by other ships, or travel by other direction than that prescribed by the Church.

At the date of the hand-cart expedition, the apostle Richards was president of the Church throughout all Europe. He was also a director of the Perpetual Emigration Fund Organization, and to him was entrusted the financial management of the entire European emigration of that year from Liverpool to Salt Lake. The apostle Taylor was at that time presiding over the Mormons in the Eastern and New England States, with New York for his head-quarters. By ordination, the apostle at New York took precedence of the apostle at Liverpool, and it is presumed entertained the idea that the arrangements for the passage of the emigrants through the States on to the frontiers should be under his direction. The apostle at Liverpool could not see things in that light—he only wanted the influence and assistance of the apostle at New York, but nothing more, and thus each misunderstood the other's position. Even inspired apostles may fail in attaining unity of purpose when the subject under consideration is the "almighty dollar."

The early months of 1856 passed away while the two apostles stood upon their dignity and arrived at no understanding, though each doubtless thought that he was right. New York waited for some request from Liverpool, and Liverpool waited with great anxiety for items of information from New York; "brother Franklin " was nearly crazy because he could not hear from "brother John," and "brother John" was perfectly innocent of thinking that "brother Franklin" wanted to hear from him at all.

After so many promises being made "in the name of the Lord" for the success of the "divine plan," it seems strange that it did not occur to Franklin to get "the Lord" to touch the intellect of John and bring them to an understanding. How contemptible appear ail the promises that "the Lord" would still the winds and the waves, would change the seasons and cause the snow to fall on the right hand and on the left for the safety of the emigrants going to Zion, while the same "Lord," whose words had been pledged thousands of times to the poor Saints, was powerless to touch either of his own apostles and bring them to comprehend that the precious lives of thousands of persons were placed in jeopardy by their selfishness or pride!