The Rocky Mountain Saints/Chapter 29

- AFTER THE PROPHET'S DEATH.

- Sidney Rigdon delivered over to Satan

- Brigham Young and the Twelve Apostles rule the Church

- Mobocracy again rampant

- Burning the Houses of the Saints

- The Expulsion of the Mormons demanded

- The Saints agree to Expatriation.

It was very natural that "the Saints" should recall to mind the sayings of their martyred Prophet when, even in the remotest manner, he had expressed an apprehension of early death—such as "I am going like a lamb to the slaughter," etc., or when he had done anything that could be interpreted as preparatory to "shuffling off this mortal coil." These were now sacred reminiscences and confirmed his prophetic character in the estimation and love of the people. Unfortunately, however, for the peace and unity of the Church, in all the multitude of his sayings and doings he made no direct and open preparation for the presidency of the Church in case of his death,[1] and thus his martyrdom wrought confusion among the disciples. They were left "like sheep without a shepherd."

The apostles Taylor and Richards were with Joseph in Carthage jail, and all the other apostles were preaching in the States. On hearing the news of the tragedy, most of them hastened to Nauvoo, to counsel together upon the necessities of the situation.

Joseph and Hyrum Smith, with Sidney Rigdon, had constituted "the first Presidency of the Church:" they were the ruling powers of the Kingdom. The Quorum of the Twelve Apostles had, in a conventional way, been recognized as equal in authority to the First Presidency:" but up to this time the acknowledgment was merely nominal. At the death of the Smiths, Rigdon alone, of the First Presidency, remained, while the Quorum of the Apostles was entire.

For several years preceding this period, Rigdon had been somewhat lukewarm and unreliable. Still, he clung to the faith, loved the Saints, and was certain to be present on the great occasions of Mormon demonstration. Sidney had never fairly got over the sufferings he endured in Missouri. His enthusiasm was chilled; and, besides this, Joseph, in seeking the hand of his daughter, Nancy, greatly offended him. At the time of the Prophet's death, Rigdon was residing with his family in Pittsburg, Ohio, trying to take life easily, while Brigham Young, the Pratts, Hyde, and other apostles were out on missions. When the news of the assassination arrived, he set out in haste and arrived first in Nauvoo. Parley P. Pratt, Brigham Young, Orson Hyde, Heber C. Kimball, and other apostles arrived soon after.

Who should rule the Church was now an open question.

Rigdon—aware of the logical fact that one is the smaller part of three, and realizing that his active fellowship with the living Joseph had been questionable for some years back—proposed to the Saints the appointment of a "guardian over the Church, a sort of regency, until further development should manifest "the will of the Lord." He had no hopes that he would then be accepted as a "prophet, seer, and revelator," though he had been ordained to all those high offices. Like a brevetted general, he had only worn his titles of glory. He was, therefore, contented to become the "guardian"—if only he could attain to that position.

Marsh had apostatized; Patten had been killed; and, by the accident of seniority, Brigham Young was at the head of the Quorum of the Twelve. No one questioned his fidelity to the Prophet up to this time; but, personally, he was remarkable for nothing—except being "hard-working Brigham "Young" He was infinitely inferior in education and mental development to the Pratts and Hyde, but the apostacy of Marsh and the death of Patten, his predecessors in the ranks of the apostles, had brought him uppermost in that Quorum.

The Church was now splitting into fragments. Many were uncertain of the future, and many more began to be doubtful of the past. In the language of Brigham, the people began to be "much every way." "Some were for Joseph and Hyrum, the Book of Mormon, and Doctrine and Covenants, the Temple and Joseph's measures; some were for Lyman Wight; some for James Emmett; some for Sidney Rigdon, and, I suppose, some for the Twelve."

Rigdon had been the Boanerges of the new faith, and had given it the first important aid which it received; but he was now waning in everything. He had seen Joseph revel in visions, dreams, and revelations, and had witnessed their wonderful effect upon the bewildered minds of the Saints. To step securely into Joseph's shoes, he had to do something like him, or to be for ever overthrown—like Lucifer, for his ambition in seeking the headship of the Church. He essayed the rôle of Joseph and entered upon the shadowy regions of revelation. He had nightly visions about Gog and Magog, and saw wonderful things which were soon to take place. The great battle of Armageddon was at hand, and Rigdon was to lead on the hosts of the Lord to the slaughter till the blood flowed up to the horses' bridles. When that was all done and got through with, he, as a conqueror, was to be privileged with the honour of "pulling the nose of little Vic.!"

This mad raving before public audiences, and the familiarity of language in using the name of her most gracious majesty, the sovereign of Great Britain, render comment on such fanaticism unnecessary. In private assemblages of the brethren he announced that he held "the keys of David," and he ordained some special friends to be "prophets, priests, and kings," and made general preparation for the maintenance of his claims, by force if necessary, to the guardianship of the Church.

Rigdon was brought up for public trial before the High Council in Nanvoo, on the 8th of September, with eight of the. apostles as "witnesses"—who in reality acted as principal accusers. Brigham led off with a speech about Rigdon's history, and was followed by the other apostles and all who had anything to say about the matter. He was charged with the determination to "rule or ruin the Church." Brigham was as determined that he should do neither. Rigdon was said to be sick, and failed to appear at trial; but that was no hindrance. The accusations were listened to, and the family quarrel was anything but edifying to the Saints. Finally, it was moved "that he be cut off from the Church and delivered over to the buffetings of Satan until he repent." To this the reporter adds:

"Elder Young arose, and delivered Sidney Rigdon over to the buffetings of Satan in the name of the Lord; and all the people said, Amen."

Some ten persons voted in favour of Rigdon, and these were immediately "suspended" from fellowship.

Brigham's notions of freedom of voting are singularly amusing. He works up his audience to the affirmative of what he has to propose, and as he calls for an expression of the people's mind by a show of uplifted hands, he stands up in the congregation to watch the operation. He then asks for a negative vote, and should any unfortunates differ from him they are captured. He has more recently added to this amusement of free voting the instruction beforehand to the congregation: "Now, brethren, look around you, and see who are voting; we want every one to vote one way or another." Should the voting be the "one way," all is serene; should it be "the other way," he then forces a collision which terminates with something analogous to King Richard's ejaculation—"Off with his head! So much for Buckingham!" Brigham's free voting assemblies closely resemble those of the ancient parliaments of France, which were only convened to ratify the arbitrary edicts of the absolute monarchs of that kingdom.

For some time after the trial, Sidney showed considerable disposition to fight the position assumed by Brigham and the Twelve, and for that purpose he revived the Latter-Day Saints' Messenger and Advocate, in Pittsburg, Pa.; but it had only a short-lived existence. He is now very feeble with age and infirmity, and living in Friendship, New York. It has been generally expected that some day he would confess to having aided Joseph Smith in fabricating, from "Solomon Spaulding's Manuscript," the Book of Mormon; but there seems to be no ground for such a hope. All through his trial those who knew him before he was a Mormon spoke of him in such a manner as leaves no room to doubt Rigdon's own sincerity in the Mormon faith, and his total ignorance of the existence of Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon till after that work had been published.

As soon as Sidney was disposed of, the change in the government of the Church was almost magical. Joseph was always gushing over with inspiration and abounding in revelations. He had one or two men around him who aided him with counsel; but, after all, Joseph was the dominant figure throughout. Over the Church there were now twelve men, most of whom were ambitious to work. They were in new spheres of action, and set out, in the language of the conventicle, to "magnify their calling."

In entering upon a new page of history, they thought it prudent to revise the past. Joseph had trusted more to miraculous interpositions, "the Lord," and outside politicians, then had been profitable. Brigham had been a hard-working man, and he knew the superiority of practical labour over visions, dreams, and revelations. He knew, too, the uncertainty of politics. He had studied Joseph's troubles, had witnessed the terrible effect of Sidney's flighty attempts at continuing revelation, and had resolved to change the thoughts of the people.

Joseph was "a natural born seer," and had a pedestal of his own. There Brigham intended that he should remain—alone and undisturbed. With Joseph among them, the Saints had "walked by sight." With Brigham, they were now to "walk by faith." That was the safer position. Instead of vaulting to the prominence of the "Revelator," Brigham brought down the revelations to the grasp of the people, and distributed them broadcast among them. "Every member," said he, "has the right of receiving revelation for himself." This was a flattering privilege, and a great consolation; it had to satisfy the Saints, and it saved Brigham the unpleasantness of comparison. "Let no man presume for a moment that his [Joseph's] place will be filled by another," was the language of the hour; "you are now without a prophet present with you in the flesh to guide you; but you are not without apostles who hold the keys of power to seal on earth that which shall be sealed in heaven . . . I am not a prophet, seer, or revelator, as Joseph was," continues Brigham; "neither do I give revelations with 'Thus saith the Lord,' as he did, and so much the better for the Saints, for if I did so, and they did not live up to those revelations, they would be condemned."

This was certainly a very kind consideration. What a deal of condemnation the Saints would have been saved if Joseph had only thought of it in his time! They now, however, had only "Hobson's choice," and were obliged to accept the situation. It is a sensible axiom that "half a loaf is better than no bread:" the Saints could not make a Joseph, they had of necessity to accept a Brigham. The soul and inspiration of Mormonism were gone. There was no successor to Joseph—there could be none. Brigham at once announced that Joseph had left enough of revelation to guide them for twenty years. To build up "the kingdom" to Joseph, and to carry out Joseph's measures, were henceforth to be ambition and glory enough. Brigham might occupy Joseph's seat on the platform, but he could never fill his place in the Church, and no one knew this better than Brigham himself. He saw before him a multitude of people who had been gathered by revelation, and who had fed upon it daily. There was but one thing that could be done—make them work out an idea. "Build up the kingdom to Joseph: build it to Joseph!"—"He is looking down upon us, and is with us as much as before." The people laboured for Joseph, and Brigham controlled and garnered the results for himself. The past style of doing business was to be changed; the loose ends were to be tied up, and everything was to be put upon a strictly commercial basis. The Saints were to gather to Nauvoo as before, but every member of the Church was to "proceed immediately to tithe himself or herself a tenth of all their property or money, and pay it into the hands of the Twelve," and "the members can then employ the remainder of their capital in every branch of enterprise, industry, and charity, as seemeth them good; only holding themselves in readiness to be advised in such manner as shall be for the good of themselves and the whole society."

Brigham meant to control everybody and everything; and from the time when he signed the first epistle—"Brigham Young, President of the Twelve, Nauvoo, August 15th, 1844," to the present hour, he has never lost sight of that part of his programme.

In politics he was equally emphatic. None of the candidates for the presidential chair had "manifested any disposition or intention to redress wrong or restore right, liberty, or law," and the Saints were counselled to "stand aloof from all men and measures till some one could be found who would carry out the enlarged principles of our beloved prophet and martyr, General Joseph Smith." In the mean time "the Twelve Apostles of this dispensation stand in their own place and always will, both in time and eternity, to minister, preside, and regulate the affairs of the whole Church."

The coup d'état that overthrew Rigdon and placed Brigham on the throne was then complete. All that remained to be done, was to officially decapitate Rigdon and hand him over to Satan, which, as before stated, Brigham duly attended to on the 8th of September.

There is something strikingly characteristic of the man in the foundation then laid of his present position. He has been charged with inconsistency in asserting at the time of Joseph's death that "no man should stand in his place," while subsequently he filled that place himself. But to this he has a ready. answer: "No one can take the place of Joseph; he is still in his place at the head of the Church, and will always be there throughout time and eternity." This language is somewhat diplomatic, but it is consistent with the whole tenor of his life—"the end justifies the means."

That the people should not understand Brigham's ulterior purposes is not a matter of surprise. He understood them himself, and seized the earliest opportunity of preparing for the contemplated change as soon as the people should be ready for the experiment. On the 2nd of September an editorial appeared in the Times and Seasons, in which occurs the following shrewd, half-expressed anticipation of the change:

"Great excitement prevails throughout the world to know who 'shall be the successor of Joseph Smith.' In reply, we say—be patient, be patient a little, and we will tell you all. 'Great wheels move slowly.' At present we can say that a special conference of the Church was held at Nauvoo on the 8th ultimo, and it was carried without a dissenting voice that the 'Twelve' should preside over the whole Church, and when any alteration in the presidency shall be required, reasonable notice shall be given; and the elders abroad will best exhibit their wisdom to all men by remaining silent on those things they are ignorant of."

That the Twelve should preside over the whole Church, is placed in the fore-ground to be seen of all men, and to be spoken of openly, but, "when any alteration in the Presidency shall be required," a silent reserve was to be maintained, which only the wise could understand. Discussion was imprudent—silence was wisdom. Shrewd Brigham!

From a neutral standpoint, and taking the two men and their antecedents into account, the Church, however little it may have gained, lost nothing by preferring Brigham before Rigdon; but to a people like the Mormons, accustomed to so much revelation as Joseph had given them, and the guidance of "the Lord" in everything—even to the building of a "boarding-house"—this period of their history is singularly suggestive.—The "Revelator" was truly gone.

The distinctive feature of Mormonism was henceforth to be implicit, unquestioning "obedience"—an utter subjugation of will and personality to the dictates of the Priesthood. "Religion was made up of obedience, let life or death come." "Satan was hurled from heaven for resisting authority."[2] The past troubles of Mormonism were all then traceable to freedom of thought. The murderers of the Smiths were "a hundredth part "less guilty than the "apostates." "A little difference of feeling; a little difference of opinion; a little difference of spirit; and this difference has finally ended in bloodshed and murder." From this time the Mormon leaders have intensely hated "apostates," and to this day they have not discovered the possibility of any person leaving the Mormon faith, without at the same time "thirsting for the blood of the Prophet."

While the Rigdon-Young difficulty about the succession was going on, Lyman Wight, one of the twelve apostles, and William Smith, another apostle and brother of the murdered Prophet, were objects of some anxiety; but the former was "let alone severely," and the latter, for a time, was spoken of with patronizing kindness as "the remaining brother of the Prophet and the Patriarch." Wight went to Texas with a small company to form a settlement. There they suffered a good deal together, and finally broke up and scattered where they could. The Prophet's brother was soon after accused of sowing his "wild oats," without proper regard to the order of the new revelation; and he was easily got rid of. He has since managed to maintain a happy obscurity.[3] John E. Page, another apostle, became discontented, apostatized, and was cut off, while Gladden Bishop, Strang, Brewster, Hendrick, Cutler, Emmett, and a host of other elders were in the enjoyment of a fearful amount of new and bewildering revelation about who should succeed Joseph Smith, and all of them opposed to Brigham Young's leadership of the Church.

Unborn, yet blessed and prophetically announced, was David Hyrum Smith, to be at some future time the ruler of the Mormon Church.[4] David Hyrum saw the light of this vain and wicked world on the 17th of November, 1844, about five months after the death of his father, and from his birth he became an object of the deepest interest to all professors of the Mormon faith.

While the dissensions which have just been noticed stamped the history of the Church with the confusion of Babel, the Gentiles were preparing anew for hostilities. The assassination of Joseph Smith was soon discovered to be a great blunder. There was nothing about the Prophet personally, and still less, if possible, about his brother Hyrum, to justify, even in the remotest manner, the Carthage tragedy. The assassins had mistaken men for principles. Joseph was a liberal, big-hearted man, and the last person whom the world would have taken for a prophet. In Carthage jail the Prophet and Patriarch were but men: in Nauvoo they were representatives of a system. The mobbers, murderers, and assassins at Carthage could extinguish the one: the other was left intact. Brigham Young with a tragedy for his text was a more difficult man to deal with than Joseph Smith with a revelation to announce.

The excitement in Hancock county was soon renewed, and the extremists on either side felt the desperation of their situation. The one sought to justify the assassination of the Prophet, the other to revenge his death. The resolutions passed at any meeting at Nauvoo or Carthage amounted to nothing with such an account unsettled there could be no honesty on either side. There were hostility and conflict of interests which no preambles, resolutions, or public speaking could affect. The Mormons hated the Gentiles, and the Gentiles hated the Mormons. This was the only point upon which they were agreed. They were each of them ready to believe and act upon the most exaggerated and groundless reports, and there was nothing too bad for either of them to credit concerning the other. Of this time Governor Ford gives the following interesting picture:

"The Mormons invoked the assistance of Government to take vengeance upon the murderers of the Smiths. The anti-Mormons asked the Governor to violate the constitution which he was sworn to support, by erecting himself into a military despot and exiling the Mormons. The Mormons on their part, in their newspapers, invited the Government to assume absolute power by taking a summary vengeance upon their enemies, by shooting fifty or a hundred of them, without judge or jury. Both parties were thoroughly disgusted with constitutional provisions restraining them from summary vengeance; each was ready to submit to arbitrary power, to the fiat of a dictator, to make me a king for the time being, or at least that I might exercise the power of a king to abolish both the forms and spirit of a free government, if the despotism erected upon its ruins could only be wielded for their benefit, and to take vengeance on their enemies. . . .

"In the course of the fall of 1844 the anti-Mormon leaders sent printed invitations to all the militia captains in Hancock county, and to the captains of militia in all the neighbouring counties in Illinois, Iowa, and Missouri, to be present with their companies at a great wolf-hunt in Hancock; and it was privately announced that the wolves to be hunted were the Mormons and Jack-Mormons.[5] Preparations were made for assembling several thousand men with provisions for six days; and the anti-Mormon newspapers in aid of the movement commenced anew the most awful accounts of thefts, and robberies, and meditated outrages by the Mormons. The Whig press in every part of the United States came to their assistance. The Democratic newspapers and the leading Democrats who had received the benefit of the Mormon votes to their party, quailed under the tempest, leaving no organ for the correction of public opinion, either at home or abroad, except the discredited Mormon newspaper at Nauvoo. But very few of my prominent Democratic friends would dare come up to the assistance of their Governor, and but few of them dared openly to vindicate his motives in endeavouring to keep the peace. They were willing and anxious for Mormon votes at elections, but they were unwilling to risk their popularity with the people, by taking a part in their favour, even when law, and justice, and the constitution were on their side. Such being the odious character of the Mormons, the hatred of the common people against them, and such being the pusillanimity of leading men in fearing to encounter it.

"In this state of the case I applied to Brigadier-General J. J. Hardin of the State militia, and to Colonels Baker and Merriman, all Whigs, but all of them men of military ambition, and they, together with Colonel William Weatherford, a Democrat, with my own exertions, succeeded in raising about five hundred volunteers; and thus did these Whigs, that which my own political friends, with two or three exceptions, were slow to do, from a sense of gratitude. . . .

"Nauvoo was now a city of about 15,000 inhabitants, and was fast increasing, as the followers of the Prophet were pouring into it from all parts of the world; and there were several other settlements and villages of Mormons in Hancock county. Nauvoo was scattered over about six square miles, a part of it being built upon the flat skirting and fronting on the Mississippi River, but the greater portion of it upon the bluffs back, east of the river. The great Temple, that is said to have cost a million of dollars in money and labour, occupied a commanding position on the brow of this bluff, and overlooked the country around in Illinois and Iowa. . . .

"The anti-Mormons complained of a large number of larcenies and robberies. The Mormon press at Nauvoo, and the anti-Mormon papers at Warsaw, Quincy, Springfield, Alton, and St. Louis, kept up a constant fire at each other; the anti-Mormons all the time calling upon the people to rise and expel or exterminate the Mormons. . . . In the fall of 1845, the anti-Mormons of Lima and Green Plains held a meeting to devise means for the expulsion of the Mormons from their neighbourhood. They appointed some persons of their own number to fire a few shots at the house where they were assembled, but to do it in such a way as to hurt none who attended the meeting. The meeting was held, the house was fired at, but so as to hurt no one; and the anti-Mormons, suddenly breaking up their meeting, rode all over the country, spreading the dire alarm that the Mormons had commenced the work of massacre and death.

"This startling intelligence soon assembled a mob at Lima, which proceeded to warn the Mormons to leave the neighbourhood, and threatened them with fire and sword if they remained. A very poor class of Mormons resided there, and it is very likely that the other inhabitants were annoyed beyond further endurance by their little larcenies and rogueries. The Mormons refused to remove; and about one hundred and seventy-five houses and hovels were burnt, the inmates being obliged to flee for their lives. They fled to Nauvoo in a state of utter destitution, carrying their women and children, aged and sick, along with them as best they could. The sight of these miserable creatures aroused the wrath of the Mormons of Nauvoo.

"When the burning of houses commenced, the great body of the anti-Mormons expressed themselves strongly against it, giving hopes thereby that a posse of anti-Mormons could be raised to put a stop to such incendiary and riotous conduct. But when they were called on by the new sheriff, not a man of them turned out to his assistance, many of them no doubt being influenced by their hatred of the sheriff. Backinstos then went to Nauvoo, where he raised a posse of several hundred armed Mormons, with which he swept over the country, took possession of Carthage, and established a permanent guard there. The anti-Mormons everywhere fled from their houses before the sheriff some of them to Iowa and Missouri and others to the neighbouring counties in Illinois. The sheriff was unable or unwilling to bring any portion of the rioters to battle or to arrest any of them for their crimes. The posse came near surprising one small squad, but they made their escape, all but one, before they could be attacked. This one, named McBratney, was shot down by some of the posse in advance, by whom he was hacked and mutilated as though he had been murdered by the Indians.

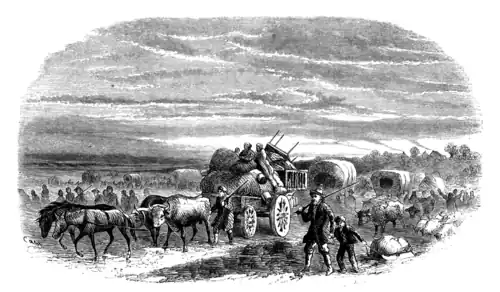

"The sheriff also was in continual peril of his life from the anti-Mormons, Image missingBurning Mormon Houses. who daily threatened him with death the first opportunity. As he was going in a buggy in the direction of Warsaw from Nauvoo, he was pursued by three or four men to a place in the road where some Mormon teams were standing. But Backinstos passed the teams a few rods, and then stopping, the pursuers came up to within one hundred and fifty yards, when they were fired upon, with an unerring aim, by some one concealed not far to one side of them. By this fire Franklin A. Worrell was killed. He was the same man who had commanded the guard at the jail at the time the Smiths were assassinated; and there made himself conspicuous by betraying his trust by consenting to the assassination. It is believed that Backinstos expected to be pursued and attacked, and had previously stationed some men in ambush to fire upon his pursuers. He was afterwards indicted for the supposed murder, and procured a change of venue to Peoria county, where he was acquitted of the charge. About this time, also, the Mormons murdered a man of the name of Daubeneyer, without any apparent provocation; and another anti-Mormon, named Wilcox, was murdered in Nauvoo, as it is believed by order of the Twelve Apostles. The anti-Mormons also committed one murder. Some of them, under Backman, set fire to some straw near a barn belonging to Durfee, an old Mormon of seventy years, and then lay in ambush until the old man came out to extinguish the fire, when they shot him dead from their place of concealment. The perpetrators of this murder were arrested and brought before an anti-Mormon justice of the peace, and were acquitted, though their guilt was sufficiently apparent.

"During the ascendancy of the sheriff, and the absence of the anti-Mormons, the people who had been burnt out of their homes fled to Nauvoo, from whence with many others they sallied forth and ravaged the country, stealing and plundering whatever was convenient to drive away.

"When informed of these proceedings, I hastened to Jacksonville, where, in a conference with General Hardin, Major Warren, Judge Douglas, and the Attorney-General, Mr. McDougall, it was agreed that these gentlemen should proceed to Hancock in all haste, with whatever forces had been raised, few or many, and put an end to these disorders. It was now apparent that neither party in Hancock could be trusted with the power to keep the peace. It was also agreed that all these gentlemen should unite their influence with mine to induce the Mormons to leave the State.

"Through the intervention of General Hardin, acting under instructions from me, an agreement was made between the hostile parties for the voluntary removal of the greater part of the Mormons in the spring of 1846."[6]

During the renewed contention the Mormons exerted every energy to complete the Temple. The faithful had been taught that they and all that was theirs should be consecrated to this great work, and themselves greatly blessed by aiding in it. They had learned that therein a great endowment would be bestowed upon the living, and peculiar privileges accorded to their dead. The faith and labours of the people were in an extraordinary degree stimulated by the announcement that if the Temple were not completed within a specified time "the Lord would reject them and their dead."[7]

The Mormons estimated this building at about six hundred thousand dollars, and in its construction and design it exhibited "more wealth, more art, more science, more revelation, more splendour, and more God, than all the rest of the world."

Their pride in this particular instance was pardonable, for the Temple was reared in the midst of great poverty, and, before they could complete it, the masons, carpenters, and artisans had their fire-arms lying beside their tools, while watchmen were continually on the alert to sound the alarm on the approach of any foe. Thus, in the New Zion, the Scripture story of the pains and perils of the Jewish builders of the walls of Jerusalem, under the guidance of Nehemiah, was repeated, which the Mormons failed not to remember, and from it made a pointed application.

Indictments had been found in the Circuit Court of the United States, for the District of Illinois, against a number of the leading Mormons, for counterfeiting the coin of the Republic, and the marshal was eager for their arrest. The Governor declined to call out the militia to support the sheriff, believing that it was better, after the calamities that had already befallen the Saints, and the promise they had given of expatriating themselves in the spring, to allow them to escape without further molestation; a conclusion which he readily reached, as he believed that none of them could be convicted.

This bogus money-making in Nauvoo has been strenuously denied by Brigham and some of the apostles, and very probably those who denied all knowledge of that business were perfectly truthful in their statements, as far as they themselves were concerned. But that bogus money was made and in circulation, in and around Nauvoo, and also was sent to a distance for circulation, can certainly not be denied. That some of "the brethren" were engaged in its manufacture seems to be well supported by facts which subsequently transpired.

No one unacquainted with the history of the Saints at this time could possibly imagine the recrimination and bitterness of feeling that existed between the Mormons and anti-Mormons of Nauvoo and the surrounding districts. It was worse than civil war, worse than a war of races; it was religious hate! It was fed by fanaticism on both sides—a fanaticism that was truly despicable. It demonstrated beyond controversy that Mormonism, and what is termed by the Saints "the world," are incompatible with each other. With the faith of the Saints that they were building up "a kingdom," it was very natural that they should act differently from the citizens of a Republic, and that they should seek to control, and not submit to be controlled. With no faith in that religion, it was as natural for "the Gentiles" to view with alarm every influence and power in the county passing into Mormon hands. The idea of subjugation was at the bottom of their thoughts, and they were determined not to submit. It was evident to every one that there could be no peace so long as the Mormons remained in the county, and for their expulsion the anti-Mormons of the neighbouring counties pledged "their lives and their sacred honour."

THE EXODUS FROM NAUVOO.

- ↑ It is claimed that "young Joseph"—eldest son of the Prophet—"was appointed through his father according to the law of lineage, by prophecy, and blessing, in Liberty jail, Missouri; by revelation in 1841, and by a formal anointing in a Council in Nauvoo, in 1844," to be the successor of his father.

- ↑ "Epistle of the Twelve." Times and Seasons, Vol. V., page 618.

- ↑ From the beginning of Mormonism the ruling authorities have accepted defamation of character as the best weapon with which to assail the discontented. Without challenging the Mormon charges against the Prophet's brother, it is due to the latter to append the following from the Clayton County [Iowa] Journal: "During the war with the South he served nearly two years as a soldier, in helping to put down the rebellion. In 1841 and '42 he served in the legislature as representative from Hancock county, in the State of Illinois. He has followed the occupation of a farmer in the vicinity of Elkader, and upon Sundays occasionally preaching. As a man, he is candid, honest, and upright—a citizen of whom rumour speaks no evil, and he is a faithful expounder of true Mormonism, while he deprecates polygamy."

- ↑ This prediction rests upon the remembrance of the Hon. John M. Bernhisel, formerly delegate from Utah to Congress.

- ↑ A slang name applied to Gentiles who favour the Mormons.

- ↑ "History of Illinois," pp. 861–410.

- ↑ In a subsequent chapter the ordinances for the dead are treated of.