The Rocky Mountain Saints/Chapter 23

- POLITICAL DIFFICULTIES.

- The Prophet balances between the Whigs and the Democrats

- The Neighbours of the Mormons become dissatisfied

- Joseph charged with Designs upon the Life of Governor Boggs

- He is arrested on a Charge of Treason

- Ways that are dark

- Governor Ford explains

- The First Budding of Polygamy

- The Beginning of the End

- Serious Charges are made.

The people of Illinois were now becoming better acquainted with their new fellow-citizens and comprehending the inevitable political issue between a community voting as a unit and the divisional voting of promiscuous citizens. Their immediate neighbours were now as dissatisfied with their presence as were the Missourians formerly, and serious charges were preferred against them.

Joseph Smith and the Mormons had their own purposes and advancement to serve, and they used the Whigs or the Democrats as best suited them. This the politicians fully appreciated and were ready for any measure that would rid them of the power that threatened to control them. Meetings and conventions were held and an anti-Mormon organization was formed for the purpose of urging the Legislature to cancel the liberal charter that had been granted to Nauvoo, to disband the Legion and, if possible, to get rid of the Mormons altogether. Whigs and Democrats were equally hostile and equally zealous in the work, but the Prophet for a time out-generalled them all and maintained his own.

A citizen of Nauvoo, in his narrative of those days and circumstances, groups together the facts and fears that then agitated the anti-Mormons:

"The issue was for the first time clearly drawn, the election in due time came off, and the Prophet was triumphant. He had elected everything on the county ticket. By his combinations he had completely defeated the anti-Mormon movement and had for county officers his trusty friends devoted to his interests. If his enemies chose to appeal from the decision of the polls, he was ready for them. His battalions were models of discipline, devoted to his service, numbered by thousands, and armed with an efficiency which distinguished no other troops in America. The walls of the Temple were progressing rapidly. The anti-Mormons looked upon the structure with many doubts and apprehensions. Everything the Mormons did was veiled in mystery. This structure resembled no church, its walls of massive limestone were impervious to the shot of the heaviest cannon. It had two tiers of circular windows which looked to the wondering Gentiles very much as if they were port-holes for the manoeuvring of cannon. The building was near the centre of a square of four acres, to be surrounded by a massive wall ten feet in height and six in thickness. This the Mormons said was for a promenade; the anti-Mormons would have told you, it could have been constructed for no other purpose than a fortification, and one which would have stood a heavy bombardment without being breached."[1]

To add to the feverish excitement, an attempt was made to shoot ex-Governor Boggs, of Missouri, at his residence in Independence. The would-be assassin in firing through the window missed the fatal aim, but the ex-Governor was severely wounded in the head. Charges were preferred against Joseph Smith and Orrin Porter Rockwell[2]—the former as the instigator and the latter as the instrument in this attempt at murder. An indictment was found to this effect and a requisition was made upon Governor Ford for the person of Joseph Smith.

A writ was issued in August, 1842, but the Prophet was protected by a writ of habeas corpus, and the matter was heard in January following before Judge N. Pope, in the United States District Court, at Springfield, which resulted in "an honourable acquittal;" the Judge directing "this decision to be entered on the records in such a way that Mr. Smith be no more troubled about the matter." Another demand for Joseph soon followed from Missouri; this time on a charge of treason, and the sheriffs of Jackson county, Missouri, and Carthage, Illinois, stole in upon him while visiting at some distance from Nauvoo; but the sleepless vigilance of the Mormons

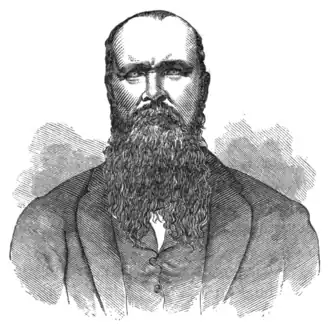

Orrin Porter Rockwell.

discovered the Prophet's critical situation in time to effect his rescue before the sheriffs could run him into Missouri. A writ of habeas corpus brought Joseph and them to Nauvoo, where the municipal court discharged the prisoner from arrest "on the merits of the case," and upon the further ground of substantial defects in the writ issued by the Governor of Illinois.

The sheriffs had used freely the muzzles of their revolvers against the ribs of the Prophet to hasten his travel from the neighbourhood of his friends, and by way of revenge, on their arrival in Nauvoo, he made them guests at his "mansion," and was profuse in kindness to them. Subsequently he sued them for false imprisonment and for using unnecessary violence in his arrest, recovering damages and costs of suit.

The Missourians, still eager for the man who had so often baffled their attempts to take him back to that State, made another application to Governor Ford, asking him to call out the militia of Illinois to effect the Prophet's arrest, but the Governor refused to do so, fearing to lose the political influence of the Mormons, which just at that time was particularly valuable to the Democratic party.

In those troublous times the jurisdiction of the municipal court of Nauvoo was a constant subject of controversy, and especially in this assertion of its right to discharge Joseph from arrest upon the writ of the Governor of the State. Cyrus Walker, a leading Whig politician and able lawyer, sustained the municipal court, and was successful in securing the liberation of Joseph; in gratitude for which the latter promised the former his vote at the pending election for members of Congress. The Democratic party in the mean time were at work with others of the leading Mormons, and "the Lord" was with them—a circumstance probably unique of its kind in political experience.

Mr. Walker very naturally highly estimated the promise of Joseph's vote, and with this imagined Mormon aid he could "read his title clear" to the House of Representatives, but, in the last moments preceding the election, Joseph's brother, Hyrum, received "a revelation" commanding the Mormons to vote for Mr. Hoge, the Democrat. Here was a dilemma! Joseph kept his word to Mr. Walker and personally voted for him, but left the people to vote for whom they pleased, assuring them before the election that he "never knew his brother Hyrum to tell a lie in his life," and thus Hoge was overwhelmingly elected.

Joseph doubtless intended, when he promised his personal vote to Walker, that the Mormons should vote the Whig ticket; but when subsequently the demand was made by Missouri that Illinois should call out the militia and take the Prophet back to Missouri, Governor Ford's refusal to so employ the militia of Illinois, and "the Lord's" revelation commanding the Mormons to vote the Democratic ticket, were plainly a very earthly negotiation. The Governor denies having been a party to this negotiation with the Mormons, but he admits that three years afterwards he learned that a prominent Democrat had given such a pledge in his name.

Politics, under the most favourable circumstances, have never been classified with the highest morality, and, to the Mormons of Hancock county, the life and liberty of Joseph Smith were of more importance than the election of Mr. Walker. Besides, the disappointed candidate could be consoled with Joseph's kindly recognition and patronage in the world to come—a promise which the Prophet Smith was never slow to make to those who served him.

This little strategy had, however, an unlooked-for and a very unpleasant issue. Governor Ford, in his "political history of Illinois," exhibits its bearing on the worldly destiny of the modern Prophet:

"It appears that the Mormons had been directed by their leaders to vote the Whig ticket in the Quincy as well as the Hancock district. In the Quincy district Judge Douglas was the Democratic candidate, O. H. Browning the candidate of the Whigs. The leading Mormons at Nauvoo having never determined in favour of the Democrats until a day or two before the election, there was not sufficient time, or it was neglected, to send orders from Nauvoo into the Quincy district to effect a change there. The Mormons in that district voted for Browning. Douglas and his friends being afraid that I might be in his way for the United States Senate, in 1846, seized hold of this circumstance to affect my party-standing, and thereby give countenance to the clamour of the Whigs, secretly whispering it about that I had not only influenced the Mormons to vote for Hoge, but for Browning also. This decided many of the Democrats in favour of the expulsion of the Mormons."[3]

Of Nauvoo, in its first flush of power, the Governor continues:

"No further demand for the arrest of Joe [Joseph] Smith having been made by Missouri, he became emboldened by success. The Mormons became more arrogant and overbearing. In the winter of 1843-4 the common council passed some further ordinances to protect their leaders from arrest on demand from Missouri. They enacted that no writ issued from any other place than Nauvoo for the arrest of any person in it should be executed in the city, without an approval endorsed thereon by the mayor; that if any public officer, by virtue of any foreign writ, should attempt to make an arrest in the city, without such approval of his process, he should be subject to imprisonment for life, and that the Governor of the State should not have the power of pardoning the offender without the consent of the mayor. When these ordinances were published they created general astonishment. Many people began to believe in good earnest that the Mormons were about to set up a separate government for themselves in defiance of the laws of the State."

This was certainly an extraordinary municipal jurisdiction, but remembering the expulsion of the Saints from Missouri, and the constantly recurring demands of its authorities, endorsed by the writs of the Governor of Illinois, for the person of Joseph Smith (with the view, as was generally averred, by both Saints and sinners, of murdering him), it is evident that the Nauvoo municipality fully comprehended the desperation of their situation. Add to this the sequel of the dastardly assassination of the Prophet and his brother, while in jail awaiting trial, under the promised protection of the Governor of the State, and the adoption of any means, however unconstitutional, which promised, if nothing more, temporary protection to the Prophet, can be readily understood.

But the trials of the Prophet were not only with the "outsiders." Trouble from within was brooding over the Church. Polygamy was dawning upon the minds of the Prophet and a few of the leading elders, and preceding shadows of something resembling "affinity," and what was termed the "spiritual-wife" doctrine, began to develop in the lives of some prominent men. This period of Mormon history is a perfect muddle of affirmation and denial, charge and counter-charge, oath and counter-oath. Men like John C. Bennett were charged by the Mormon leaders with the grossest corruption and marital infidelity. They, in turn, reversed the responsibility, and charged Joseph with teaching it to them. Councils were afterwards held, trials, witnesses, "confessions," and "forgiveness" were recorded, then soon after some new phase of the same kind of dark work was again revealed, the accused were "excommunicated" for their "iniquities" and "corrupt practices," and an irreconcilable breach was made. The testimony on both sides is so perfectly bewildering that even to-day may be found, in Salt Lake City, a husband and wife in the Mormon Church, much affected by a circumstance of these times, who are still as valiant as ever—the husband in asserting the immaculate purity of the Prophet, and the wife as stoutly asserting the opposite—from her own knowledge.

Surrounded, as Joseph Smith was at that time, with so many difficulties, it would be reasonable to expect that he would have been extraordinarily circumspect in the introduction of any proposed change in the marital relations; but with all his caution he was unsuccessful in protecting himself from charges of the gravest description. His revelation on polygamy contains sufficient evidence that he regarded the Christian marriage as utterly wrong, and that the ceremony of any priest was valueless in comparison with his own order of priesthood; but that he advocated, or in any way countenanced, the promiscuous intercourse that was charged to him by such men as Bennett, the Author has been unable to find any evidence beyond that of the one lady alluded to, and whose statement is somewhat neutralized by the fact that it is made as a countercharge to one of Joseph's, accusing Bennett of the outrage of an absent husband. Many, however, believe the lady's statement.

Bennett made a tour through the West, lecturing on the enormities of Mormonism, and stirring up the people to mob-violence, while Francis M. Higbee had Joseph arrested for defamation of character, on a writ granted by the circuit court of Hancock county. But the municipal court of Nauvoo, ever ready at his call, protected him with a writ of habeas corpus, and on examination he was discharged on the ground that the suit was instituted through malice.

- ↑ This reported enormous strength of the Temple and wall was purely imaginary.

- ↑ "Port," as he is generally termed, is commonly credited with being the chief of the Danites. He was a faithful friend of Joseph, and in moments of danger was ever near the Prophet. He was apprehended and tried on this charge, but was able to prove that he was a few miles distant from the place at the time of the attempt at assassination. The firing was probably the act of another, but he, doubtless, was no stranger to the Mormons. The Governor owed his preservation to the misdirection of the assassin's pistol, "caused by the reflection of the light upon the window glass." It is said that Joseph promised "Port" protection to his life so long as his locks were uncut. This story smacks something of Samson and Delilah; "Port," however, still wears unshorn locks.

- ↑ Ford's "History of Illinois," p. 320.