The Last Link/Geological Time and Evolution

GEOLOGICAL TIME AND EVOLUTION.

One million years is a stretch of time beyond our conception. We can arrive at a more or less adequate understanding of what a million individuals or concrete things means. Several Continental nations can put more than a million men into the field. We can gaze at a building which contains as many bricks; and we know that our own body is composed of millions of millions of cells. No such help applies to time, because that itself is an entirely relative, abstract conception. We can imagine what one hundred years are like—a span of time seemingly short to the hale and hearty octogenarian, enormous to the child, totally inapplicable to certain animals whose whole life is crowded into one single day.

Astronomers have long ceased to reckon distances by miles or any other understandable unit. They express the distances between us and the stars and nebulæ by 'years of light.' Try to imagine a unit of length equal to that which is passed through by light (186,000 miles per second) in one year. Not so very long ago the enormous distances resulting from astronomical calculations were looked upon as the most serious objection to the correctness of the astronomers' views as to the distances which separate our globe from the nearest fixed stars. We have not yet accustomed ourselves to reckoning time by some similar broadly-conceived standard—say æons of so many thousand years each.

Unfortunately, we possess no data whatever for calculating the age of the successive geological strata. Thanks to Lyell, the theory of violent universal cataclysms has been done away with. It is more probable that the same agencies have acted which are now changing the aspect of the globe; and these changes are slow, as far as we know them—at least, as far as the formation of sedimentary strata is concerned, and these alone we have to deal with. Various calculations have been made, based upon the denudation of the mountains, the filling up of the valleys by the débris, the formation of deltas, etc. The results give enormous stretches of time, but all of them unsatisfactory, because the methods are so very local in their application.

The least objectionable attempt is that which, based upon astronomical calculations, tried to fix the height of the last Glacial epoch[1] at about 200,000 years ago, and asserted that since its beginning in the Pliocene epoch as many as 270,000 years have elapsed. The duration of the whole Tertiary period has by the same authorities been fixed approximately at 3,000,000 to 4,000,000 years. Beyond this we cannot venture without the wildest speculation; but we know to a certain extent the thickness of the various sedimentary strata, which amount in all to from 100,000 to 175,000 feet—on the average perhaps 130,000 feet, or about twenty miles.

Unless we prefer giving up all attempt at calculation as absolutely hopeless, and thus resign the whole problem, we must at least try to arrive at some results, and then see if these cannot reasonably be made use of.

Neither geologist nor physicist, and no zoologist, would accept the suggestion that these 130,000 feet of stratified rocks have been deposited within only as many years, although the average rate of deposit would in that case be not more than 1 foot per year. On the other hand, an indignant protest is raised against the assumption of 1,000,000,000 years.

Lord Kelvin[2] has come to the conclusion (from data which various other authorities regard as very unsatisfactory) that not much more than 100,000,000 years can have elapsed since the molten globe acquired a consolidated crust. Further time must have passed before the surface had become stable and cool enough to allow the temperature of the collecting oceans to fall below boiling-point, and it is obvious that life cannot possibly have begun until after this had happened.

Wallace, in his 'Island Life,' by making use of Professor A. Geikie's results as to the rate of denudation of matter by rivers from the area of their basins, and estimating the average rate of deposition, concludes that 'the time required to produce this thickness of rock [Professor Haughton's maximum of 177,000 feet] at the present rate of denudation and deposition is only 28,000,000 years.' Our lower assumption of 130,000 feet thickness would give only 20,000,000 years—a rate of 1 foot in 154 years.

Again, if we prefer round numbers to start with, we have only to assume that the age of the whole Tertiary period, with its 3,000 feet thickness, is 3,000,000 years (i.e., 1,000 feet in 1,000,000 years, or 1 foot in 1,000 years, surely an excessively slow rate); then 130,000,000 years would bring us to the bottom of the Laurentian or pre-Cambrian deposits. Of course, it is a pure assumption that the same rate of destruction and sedimentation applies to the whole of the strata; but we know nothing to the contrary, especially if we consider the average periods, the quick periods of extra activity, taken with the slow periods or those of standstill.

Dana estimated the length of the whole Tertiary period at one-fifteenth of the Mesozoic and Palæozoic combined. If we take the duration of the Tertiary period, as before, as 3,000,000 to 4,000,000 years, the total will amount to from 45,000,000 to 60,000,000 years.

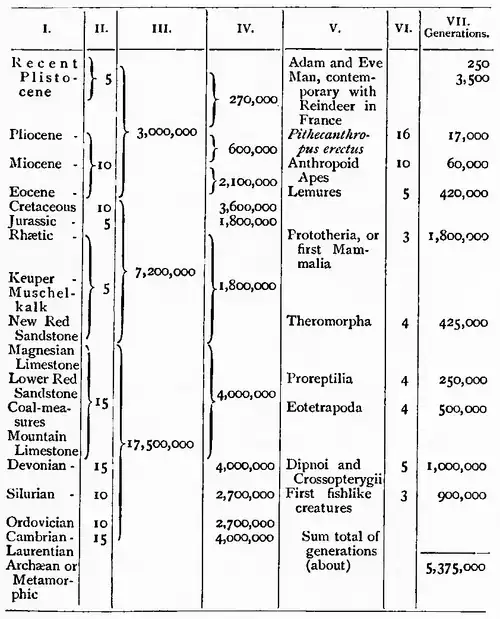

Lastly, Walcott[3] has estimated the duration of the Palæozoic, Mesozoic, and Cænozoic or Tertiary epochs at about 17,000,000, 7,000,000 and 3,000,000 years respectively, giving 27,700,000 years from the beginning of the Cambrian; and Williams[4] has calculated the relative duration of the smaller epochs. See the table on p. 149.

The results of all these calculations fall surprisingly well within the limits of Lord Kelvin's allowance. Of course they are based upon assumptions, but none of them is inherently unreasonable; and it was my purpose to draw attention to the surprising coincidence in the closeness of these results, perhaps too good to be true. Such calculations are considered close enough if they range within a few multiples of each other.

Zoologists have fallen into the habit of requiring enormous lengths of time for the evolution of the animal kingdom. We know that Evolution is at best a slow process, and the conception of the changes necessary to evolve man from monkey-like creatures, these from the lowest imaginary mammals, these from some reptilian stock, thence descending to Dipnoan fish-like creatures, and so on back into Invertebrata, down to the simple Monera—this conception is indeed gigantic. Innumerable, almost endless, slow changes require seemingly unlimited time, and as time is endless, why not draw upon it ad libitum?

Huxley pointed out that it took nearly the whole of the Tertiary epoch to produce the horse out of the four-toed Eohippos, and that, if we apply this rate to the rest of its pedigree, enormous times would be required. This is, however, a very misleading statement, which necessitates considerable reduction, in conformity with our increased palæontological knowledge. Animals of the genus Equus—namely, Ungulata, with one toe, and with a certain tooth pattern—from the Upper Miocene of India are now known. Moreover, it is not simply a question of the gradual loss of the side-toes. The change from the fox-sized little Eohippos and Hyracotherium, so far as skull, teeth, vertebral column, and limbs are concerned (about the soft parts we know next to nothing), is a very great one indeed.

Elephants and mammoths seem to have developed very rapidly. None are known from Eocene strata; but towards the end of the Miocene they had spread over Asia, Europe, and North America, and that in great numbers. The Eocene Amblypoda are still so different that we hesitate to connect them ancestrally with the elephants.

The Pinnipedia (seals and walruses) are strongly modified fissiped Carnivora, and have existed since at least the Upper Miocene; the transformation must have been accomplished within the Miocene period.

We cannot shut our eyes to the fact that various groups have from the time of their first appearance burst out into an exuberant growth of modifications in form, size, and numbers, into all possible—and one might almost say impossible—shapes; and they have done this within comparatively short periods, after which they have died out not less rapidly. It seems almost as if these go-ahead creatures had, by accepting every possible modification and carrying the same to the extreme, too quickly exhausted their plasticity—which, after all, must have limits—thereby becoming unable to meet successfully the requirements of further changes in their surroundings. The slowly developing groups, keeping within main lines of Evolution, and not being tempted into aberrant side-issues, had, after all, a much better chance of onward evolution.

A good example of the former are the Dinosaurs. We do not know their ancestors; but we have here to deal only with their range of transformation. The oldest known forms occur in the Upper Trias; they attain their most stupendous development in the Upper Jurassic and in the Wealden; and they have died out with the Cretaceous epoch. But already some of their earliest forms had assumed bipedal gait, and the Oolitic Compsognathus had developed almost bird-like hindlimbs.

On the other hand, there are many instances of extremely slow development—facts which raise the difficult question of 'persistent types.' Are these due to a state of perfection which cannot be improved upon? Or are they due to a kind of morphological consolidation (not necessarily specialization) which can no longer yield easily, so that therefore through changes in their surroundings they may come to an end sooner than more plastic groups?

Struthio, the ostrich; Orycteropus, the Cape ant-eater; Tapirus, and many others, existed in the Miocene age practically as they are now; but pre-Pliocene dolphins, cats, monkeys, stags, all belong to closely-allied and well-defined 'genera,' but different from the living forms.

Alligators and crocodiles are known from the Upper Chalk; Tomistoma since the Miocene; Gavialis since the Pliocene.

The oldest surviving reptile is Sphenodon, the Hatteria of New Zealand, a fair representative of what generalized reptiles of the later Triassic period seem to have been like; and to the same period belongs Ceratodus, the Australian mud-fish, hitherto the oldest known surviving genus of a very ancient and low type so far as Vertebrata are concerned.

Now let us see if the above estimates of geological time are so utterly inapplicable to animal evolution. On purpose we take one of the lowest estimates, about 28,000,000 years, and apportion them equally to the various strata or epochs.

The original owner of the famous Trinil skull, a Pithecanthropus erectus, lived, according to some, in the Late Pliocene, according to others in the Early Plistocene, period—that is to say, somewhere about the beginning of our last Glacial epoch, some 270,000 years ago. Assuming that he and his like reached puberty at sixteen to twenty years of age, about 17,000 generations would lie between him and ourselves, or, to put it more forcibly, between him and the lowest living human races—say the Ceylonese Veddahs. Only 250 generations, at twenty years, carry us back to 3000 B.C. (i.e., beyond the ken of history); and if it be objected that the differences between the oldest inhabitants of Egypt, the Naquada, and the present Fellahin are very slight, we are welcome to multiply these differences sixty or seventy fold, in order to arrive at the Pithecanthropus level. But these Naquada had no metal implements, and there cannot be the slightest doubt that the development of the human race went on by leaps and bounds after certain discoveries had been made—to wit, the use of implements and that of fire. That creature which first took up a stone or a branch and wielded it thereby got such an enormous advantage over his fellow-creatures that his mental and bodily development went on apace. The same applies to the improvement of speech. We assume the single, monophyletic origin of mankind at one place, in one district; and the differences between some of the races of man are great enough to constitute what we might call species. Compare the Venus of Milo, that noble expression of the ancient Greeks' notion of female beauty, with the 'products of art' of the Veddahs or the dwarfs of Central Africa, or think of the beau-idéal which a Michael Angelo could possibly have evolved if he had never seen any but such people.

Explanation of the Table on p. 149.

Let us follow the descent of man further back. The next stage, reckoning backwards, is that from Pithecanthropus to bonâ-fide anthropoid apes. They are represented in the Miocene by various genera—e.g., Pliopithecus and Dryopithecus. According to Croll and Wallace, 850,000 years ago carry us into the Miocene epoch. Assuming that these apes lived about 600,000 years before Pithecanthropus, namely, in the later half of the Miocene, and taking puberty at ten years of age, a high estimate, we get not less than 60,000 generations.

2. From Apes back to lowest Lemurs in the lowest Eocene. The date of Eocene being fixed at 3,000,000, we have about 2,100,000 years for this stage; assuming as much as five years for puberty, this results in 420,000 generations.

3. From Lemures to Prototheria. The earliest known mammalian remains come from the Rhætic, or top formation of the Triassic epoch; allowing for the Rhætic only 100,000 years, we have to add the whole of the Jurassic and Cretaceous, in all about 5,500,000 years. Assuming three years for a generation, we get 1,800,000 generations.

4. From Prototheria to something like the Theromorpha at the bottom of the Triassic strata. A duration of 1,700,000 years divided by four gives 425,000 generations.

5. From Theromorpha to Proreptilia, represented by Eryops and Cricotus from the Lower Permian of Texas. Allowing 1,000,000 years, each generation at four years, we obtain 250,000 generations.

6. From Proreptilia to Eotetrapoda, the first terrestrial Vertebrata, represented by something like the Stegocephali, the earliest of which are known from the Coal-measures. Assuming them to have come into existence at the bottom of the Coal-measures, for the duration of which we may guess 2,000,000 years, we get, with four years' allowance for puberty, 500,000 generations.

7. From Eotetrapoda to a not yet separated or differentiated group of Crossop-terygian and Dipnoan fishes, both of which are known from Devonian strata. The duration of the latter has been computed at 4,000,000 years, which, with 1,000,000 for the Mountain Limestone formation, gives us 5,000,000 for this stage. Assuming, for the sake of round numbers, as much as five years for a generation, we get 1,000,000 generations.

8. Earliest stage, down to the first fish-like creatures. Teeth and spines indicating the existence of fishes are known from the Upper Silurian. By carrying the earliest fishes down to the bottom of the Silurian, with 2,700,000 years' duration, and allowing three years for attaining puberty, the calculation results in 900,000 generations.

Further back we cannot go. We do not know of any Vertebrate remains from the Ordovician and Cambrian, which together represent 6,700,000 years, enough for at least half as many generations of Prochordate creatures. The pre-Cambrian or Laurentian epoch lies quite beyond the reach of calculation, nor have we any trustworthy fossil remains of living matter from these strata, to which, however, Haeckel and others refer the first beginnings of life.

All the above calculations are, of course, only approximate. What we do know is the existence of representatives of the stages, our proofs being the fossils; but when we refer the origin of the Eotetrapoda, for example, to the bottom and not somewhere to the middle of the Coal-measures, we are guessing merely. Alterations in the levels assumed for the various stage-representatives will, of course, alter the result of the number of generations; but the leading idea, as a whole, is not thereby upset. The fact remains that in the Upper Silurian we have fishes; from the Coal-measures onwards, fishes and Amphibia; since the Permian, fishes, Amphibia, and reptiles; since the end of the Trias these three classes and the Mammalia; and lastly, at least since the Plistocene, man himself. If Evolution is true at all, the transformation from early fish-like creatures to man has come about within these epochs. Being able to assign a time of duration to each of them, with an approximate total of 21,000,000 years, we are also able to put the whole ancestral series to a test by expressing each great stage in generations. The result is very satisfactory. The whole enormous stretch from the lowest fish-like creatures to man has been resolved into more than 5,000,000 successive generations, and each of these means a little step forwards in onward Evolution.

Nothing is to be gained for the understanding of our problem of Evolution if we multiply this enormous number of generations by ten or any other multiple. We are not able to conceive changes so small as those which necessarily have existed between Pithecanthropus and man if the whole striking difference is analysed into 17,000 steps. Every one of these stages in the modifications of the muscles, the skeletal framework, increase of brain, shortening of the trunk, lengthening of the legs, improvement of the hands, loss of the hairy coat, etc., is truly microscopical, imperceptible, just as the Evolutionist imagines the whole process to have been. Again, where is the difficulty implied by the change from an air-breathing, in many structural points half-amphibian, fish into a primitive land-crawling four-footed creature, if we are allowed to resolve the transformation into 1,000,000 stages? So far from there being any difficulty, rather does it appear questionable if so many infinitely small changes have been necessary to bring about this result.

One thousand years make apparently no difference in the evolution of animals, nor does one second change the aspect of the hands on the face of a clock, nor did Julius Cæesar's commission of scientific men appreciate the error of about eleven minutes in the length of the year beyond its real value; but now the Russians are, owing to this neglect, nearly two weeks behind the civilized nations.

THE END.

BILLING AND SONS, PRINTERS, GUILDFORD.

- ↑ James Croll: 'On Geological Time, and the Probable Date of the Glacial and Upper Miocene Period,' Philos. Magazine, xxxv., 1868, pp. 363-384; xxxvi., pp. 141-154; 362-386.

- ↑ William Thomson: 'On the Secular Cooling of the Earth,' Transact. R. S. Edinb., xxiii., 1864, pp. 157-169.

- ↑ 'Geological Time as indicated by the Sedimentary Rocks of North America.' Proc. Amer. Assoc. Adv. Sci., xlii., 1893, pp. 129-169.

- ↑ Henry Shaler Williams, 'Geological Biology.' New York, 1895.