The Czechoslovak Review/Volume 4/Number 5/Excursion

Excursion

By DONALD BREED.

As spring came on, we all began to yearn toward the soil. Miloš showed this by lengthy perusals of the latest Jizdní Řád, the railway guide book, which he had bought at Vilimek’s book store. The Jizdní Řád was a seductive thing, for it showed you how easily one could step aboard a train and find himself within a few hours in the Giant Mountains or the Bohemian or the Moravian hills. It was also a snare and a delusion, for unless you studied it carefully you were apt not to observe the neat little foot notes which explained, in the fewest words possible, that the running of this train or that had been cancelled for the present. But Miloš read assiduously every evening after dinner, and soon became expert in all these pathological conditions of the time tables. Outside of the Ministry of Railroads, I do not believe there was a man in Prague more versed in the lore of arriving and departing trains.

Milada gave up the Jízdní Řád after a brief and unsatisfactory perusal, but she continued to share the pleasurable uneasiness of her husband. She used to go out on the kitchen balcony and remain there, with her elbows resting on the iron railing, gazing down into the little back garden of the apartment building, where a venerable creature moved mysteriously about spading up the earth and planting seeds. I found her out there one morning and took advantage of the brilliant sunshine to make a snap-shot. She was laughing, and it turned out a very good picture, as Milada readily agreed. This, of course, proved that she was singularly free from vanity. A woman who is satisfied with snap-shots of herself is a rare phenomenon, and therefore to be admired and praised when she is discovered.

Finally it was left for me, with my American impulse to action, to transform these fluttering desires into plans. It was I who obliged Miloš to confine himself to a few trains instead of spreading over the entire guide book. It was I who wheedled Milada into baking koláče and packing knapsacks. It was I who sent our oldest shoes down to the cobbler in the basement for one last siege of mending and overhauling. Mařena of the kitchen sighed as she took them down, for she knew that all man-made foot gear has a limit of repairability, and our shoes had virtually reached that limit. It was not I, however, who decided where we should go, for it was all one to me whether we went east, west, north or south, and I much preferred to start out with a feeling of adventurous vagueness regarding our destination. Miloš at length proposed that we should go up in the vicinity of Turnov. This was not because he wanted to see Turnov again, but because the Turnov train left at seven in the morning. All the others went earlier, much earlier. Inasmuch as we had seats for the theatre on the evening before our day of leaving, this was a matter of some importance to us. On such slight considerations do the balances of the gods turn.

The Turnov train, when we duly achieved it, proved to be one of those leisurely creations, which, in America, are popularly thought of as indigenous to the state of Arkansas. As we wandered from one station to the next, we had the opinion that no other trains in Bohemia could possibly be going slower than ours. Yet there was at least one such. Just beyond Mladá Boleslav we drew up beside a troop train that had obligingly got itself out of the way for us. It was made up of about fifteen little box-cars out of whose windows and doors uniformed soldiers were hanging and leaning. Milo opened the window of our compartment and shouted a greeting to them. This they acknowledged in a friendly, bellowing style, and we fell into conversation. They told us they had left Prague the previous night at nine o’clock and had been traveling intermittently ever since. Over a distance which we had covered in less than three hours they had been crawling for more than twelve. After hearing this, Miloš felt so sorry for them that he hunted about for some cigarettes to give them. But he had only a box of one hundred, and they would not have gone far with the car-full of soldiers, whereas they would keep Miloš happy for several days. Therefore, he pocketed his cigarettes and his generosity and let Milada do the agreeable thing instead. This she did to perfection. She beamed through the open window and joked with the soldiers to such an extent that they gave her a roaring ovation when we moved off.

Standing on the platform of the Turnov station, we were confronted with the necessity of making a choice. Miloš now disclosed that the next stage of our progress would involve a railway journey of a kilometer or two to a little cross-roads station from which we would proceed on foot. Our train would leave in half an hour. In the meantime we could deploy ourselves sight-seeing in Turnov, or we could eat luncheon in the station restaurant. Here was a dilemna of the gravest sort. It was solved at length by Milada, whose feminine intuitions revealed themselves more and more as equal to any situation, however trying. Milada deposed that Turnov was a permanent fixture, while luncheon was not. Turnov would remain there for months and years to come, and we might come back perennially to see it. But with luncheon it was now or never. Viewed in this light, the problem became easy. So we went into the station building, pre-empted a table and demanded to be given a meal. This, when it came, was not very good, and I remember that we were somewhat disposed to blame Milada because she had let us in for it. But Milada behaved serenely in the face of criticism and affirmed that food was good, and we would agree with her later in the afternoon. Of course she was quite right, as we subsequently admitted of our own free will.

After luncheon, the other train arrived and carried us away. We alighted at a depot-house which belonged to one of the more removed suburbs of Turnov. Possibly in the early morning it was a rallying-point for Turnov commuters, but I suspect not, for I do not think the Turnovers ever really commute. It is American to commute, just as it is Scotch to dance the Highland Fling, or Spanish to goad bulls, or French to be vinously disposed and fond of revues.

From the little depot-house we took an uphill path through a field. The field was a bare place, covered with scrubby grass, scattered stones and a few insignificant flowers that poked up between clods of earth. There was a lark singing loudly somewhere out of the blue, although it was already afternoon. Miloš objected to him on the ground of untimeliness, but I set myself up to defend him, and Milada eventually judged that he was entirely excusable for making a mistake about the time of day, because the season was so young that one time was a good deal like another. The period of drowsy, spellbinding mid-days had not yet set in.

We went on and up. On the summit of the hill was a man-built observatory reached by a short flight of winding steps. To its top platform we ascended, and looked out over a land covered with spring haze. In every direction were flowering orchards, some pink, some white. The nearer ones were positively lustruos; they glowed with a soft light that was self-created and not merely reflected from the sun. The farther ones were nothing but luminous spots. These groves of fruit-trees were the spectacular element in the landscape. The intervening spaces were quiet. It was all rolling country, partly pasture partly tilled fields and meadow. Bold on the northern horizon rose the hill and fortress of Ještěd. From that high landmark we could have seen a far wider sweep of Bohemia, the giant Mountains, and far into Saxony. Yet what was visible from our pigmy tower sufficed to loose the springs of patriotic emotion in Miloš.

“Our land!” he exulted, and began addressing it in passionate apostrophe. “Free at last! Free after centuries of bondage! No longer leased out to a Hapsburg tenant who turns about and ejects the rightful owners! No longer ours to look at and yearn for, but ours to cry aloud and rejoice in. Bohemia! Our homeland! Do you know what that means to me, you American?”

Immediately afterwards he sighed. Neitheir Milada nor I said a word, but we knew what that sigh meant. He was thinking of the birth-throes with which the new state had come into being. He remembered lonely men dying in far lands, women and children going about starved and freezing in Prague, and those social nightmares which are the camp-followers of war: mass demoralization, class extravagance and industrial chaos. The three of us gazed silently over the smiling country for a little while. Then we turned and went down the stairs from the observatory.

The next section of the walk was along the edge of an evergreen grove, out of which we were barred by a tall but flimsily built wooden paling. The path we trod on was not always even, and we talked in fits and starts of leaping over the paling or taking other bold steps of a sort to gain the coveted territory on the other side where the walking was better. Presently we had our opportunity to cross over iwthout athletic exertion. We came to a convenient gap, left by some ruthless invader, and through it we stepped. It was cooler in the shadow of the trees, but it is woefully characteristic of the human disposition to depreciate that which has once been attained and therefore Milada began to realize that she had a conscience and to speak regretfully of us as trespassing gypsies. She reminded us that we were undoubtedly where we had no business to be, and longed to be on the outside of the barrier again. An unwary suggestion by Miloš that we might be on somebody’s game preserve aroused her still more, because that meant that there could be wild animals somewhere about. She and Miloš began arguing and continued to have it back and forth for several minutes, during which time we found another hole in the fence and emerged once more on the public way. I think they were still arguing when we came upon Wallenstein’s castle.

Wallenstein’s place clings to the brow of a precipice. Parts of it overhang, and some day there will be a tremor of the earth and the whole pile will go tumbling down into the valley. This does not seem to concern the family of agreeable souls who live in it, and act as custodians of the premises. They apparently feel that a catastrophe which has so long impended will probably never happen, at least not in their day. They ought to have more consideration for their children and their children’s children who will probably be caretakers in the days to come. Milada and I had a brief but serious talk about this singular hard-heartedness of theirs, but concluded that, on the whole, it was not our duty to sow the seeds of moral rectitude in the minds of otherwise decent people. Besides, the keeper’s wife brought us such excellent cake and coffee with milk that we felt it would be our part to intercede for her on the day of judgement even if she should take it into her head to pitch her offspring, each and all, over the battlements some morning before breakfast.

The castle is more than half ruined, but a few ill-advised attempts have been made to restore parts of it. The only effect of these restorations is to make one feel that none of the old strongholds, however picturesque, could ever have been habitable places. The living-rooms in the house which was once Wallenstein’s glory now look like dismantled tombs. They are dismal and grin and the cobwebs swing in ropes from the ceilings. As I passed thru them, a shiver of pity bestirred me on behalf of the people who once had to live there. Not Wallenstein himself, for that gory old person was always so busy planning atrocities that I do not suppose he had time for aesthetic particulars, but I did feel sorry for his wife and his mother-in-law and possibly a maiden aunt or so. At the same time I presume my sympathy was unnecessarily bestowed, for if one were to move about two-thirds of the furniture out of a modern house, substitute hideous copies for the pictures on the wall, and end by finger-printing the wood-work and flinging handfuls of dust broadcast, he would produce a devastation as depressing as that of a badly restored castle.

This is really beside the point, because we all enjoyed Wallenstein’s very much, and Milada got a particularly rare degree of pleasure through venturing out on a projecting nose of rock which was labelled “dangerous to life.” After we had seen the banqueting-hall and the chambers, we sat down for few minutes in the sun, and Miloš diverted himself by telling us stories. Then we took the road again.

The trail led for several hundred yards on the verge of the cliff. There was a broad view, and the sunlight was beginning to wane. The foreground bristled with a cluster of eccentric rock columns, extremely high, like square pillars. A few leaned slightly, but most of them stood upright and tried to look impressive in spite of the puny trees which had impudently started to grow on their summits. Some of these chimney formations came so close to the rock wall that it was possible to spring over to them, and we tried one such spring, just for the sake of the sensation, but it was not much fun. The landscape was really too fine and the daylight was going too fast to waste time in sport like that. So we lay on the grass for a time, absorbing, and then adjusted our knapsacks and went on.

It was not far to Hrubá Skála, where the Austian minister, Baron von Aehrenthal, owned a castle. He it was, I believe, who said on a certain well-remembered occasion: “These wretched Czechs! They ought to be exterminated, root and branch. Let them wait. Their day is coming!” It was a curious proof that their day had really arrived, when Miloš went serenely up to the gate of the castle and knocked, requesting admittance for himself and wife and an American. The lodge-tender, who was a German, and like to die with humiliation, went off to find the resident keeper, who came and received us with great courtesy. We explained that we were interested in old castles, and he immediately conducted us about. There was a richly colored old porcelain stove that we liked, made out of the fragments of a still larger and older one which, in the course of time had collapsed and been removed to some obscure store-house, where one of the Aehrenthal family found it. There was also a curious set of chess-men, and an enormous clock, and some intricate wood-carving.

The keeper talked with us about the ruin of Trosky, which is easily seen from Hrubá Skála, but he warned us solemnly against going there. For it appeared that there had long been only one guide who was capable of leading travelers up the beetling hill and through the crumbling halls and balconies. This man was only considered reliable when slightly drunk, but it appeared that his favorite beverages had so stolen a march upon him that he now spent most of his days in a state of torpor. I am bound to say that we did not put much faith in the keeper’s story and, when his back was turned, we debated just what he meant by it. Miloš thought he probably wanted to guide us there himself and receive pay for it, Milada believed it was the influence of spring or that love might have made him temporarily mad, while I in a riotous burst of imagination, conceived that there might be German propaganda books stored in the deserted rooms of Trosky or insidious printing-presses operating by moonlight. At any rate, we decided not to go up there, and, after we had shaken hands with the keeper and given him good day, we walked across the open square of Hrubá Skála and turned down into the Mouse-Hole.

Everyone who knows anything about this art of Bohemia knows about the Mouse-Hole. It is a great descending crack in the rock, so narrow and deep that a damp twilight forever holds sway in its lower recesses. The Mouse-Hole is a freakish exhibition of Nature, something to sit down and laugh at, except that the sudden way it opens up on the edge of the Hrubá Skála square makes it momentarily rather awful. Stone steps run down through it to the valley below, and the really notable thing about it is that it is a public thoroughfare, constantly used, and not a mere curiosity. As we went down into the Hole, I had no idea of meeting anyone, but when we were half-way an old peasant woman suddenly came in sight around a corner pensively urging three she-goats along the upward course. She stared and nodded at us, and Miloš and Milada gave her a polite salutation. But I did not. The manner of her appearance made her seem like one of those spirits which are not natural, and the sombre light of the place caused the animals to take on the look of astral goats. I afterwards regretted that I had not spoken, but it was too late to go back and atone for my discourtesy. If this be rudeness, thought I, then, old woman, you must just make the most of it.

The walk from the lower mouth of the Mouse-Hole led over a pleasant road which was first arched over with trees and then bordered with villas. It led us to a railway station in the midst of fields, and we waited there and lay on our backs, blinking up at the cloudless sky until a train arrived. This train conveyed us to Jičín.

It was in Jičín that Miloš broke the clasp of his nose-glasses. Being blinder than a bat without them, he felt that he must have the damage repaired at once. So he went to a purveyor of spectacles, but it was so late that the shop was closed, and he set off on his rounds to find another, leaving Milada and me to walk about and see the statues for which Jičín is noted. There are three, in particular, which one must see: statues of Hus, Havlíček and one other. We admired them, but immediately afterward we encountered something which diverted us much more. Two wagon-loads of komedianti, itinerant players, came into the town, and we joined the gang of small boys who followed them through the winding streets. The vehicles in which they traveled looked like house-boats on wheels. They swayed and wobbled from side to side, and I know the occupants must have been good sailors or they could not have stood it. From the tiny piece of stovepipe which stuck out of the roof of each, smoke was ascending, and the damp pasty smell of dumplings came through the open window. The drivers of the two wagons were gypsy looking fellows, burnt black by the sun.

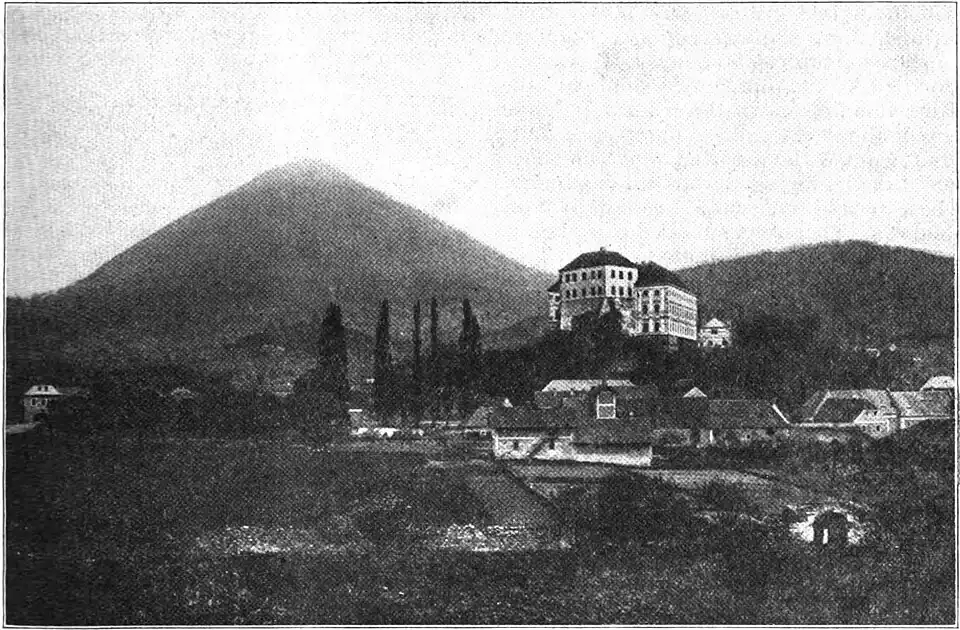

Mount Milešovka in Northern Bohemia.We followed them from one place to another and might have gone along to theircamp and eaten supper with them, if Miloš had not suddenly come charging under an arch-way toward us, conjuring us to listen to his account of the way he got his glasses fixed. According to his eloquent representations, it happened somewhat in this way.

It seems that he finally found a shop which was not closed, and a damsel was working with a broom, sweeping it out. He asked her if she thought the proprietor would repair the clasp for him, to which the maiden made spirited answer that she was perfectly sure he would not, because it was after hours. Miloš then began to plead that he could not see the road, the houses, the signs, and so on, but the girl with the broom was as unsympathetic as a piece of flint. After some minutes of such sparring, Miloš deliberately went over to the work-table, and sat down at it, hunting about for tools. The girl asked him what he was doing. Milox replied that he was going to fix it himself, whether or no, because he was determined to see her through the glasses and find out whether her looks were as cruel as her disposition. This, we were led to believe, melted the heart of the fair creature so completely that she sat down and did the work for him herself.

Milada had remained silent during this recital and when it was finished she began, to my great surprise, to tell of some interesting passages between herself and the driver of one of the komedianti wagons. There was not a single word of truth in the whole of her story, and I could do nothing but gulp and suppress my hilarity. Miloš, however, took it very seriously. Milada told how violently the man had been impressed by her theatrical presence, and how he had tried to persuade her to join his troupe. After this, I observed that we heard no more about the nymph in the optical shop. While Miloš was poring over the Národní Listy after dinner that night, I took Milada to ask for her prevarications. I could not help thinking she was rather brazen about it. She said she knew I had been shocked, but she really could not let Miloš go about fascinating all the sweeping ladies in the shops. He was, she added in a dreamy tone, altogether too good at that sort of thing.

Jičín in late evening was a city transformed. Bare spots and dingy corners disappeared. Streets and house-fronts were glorified by the mellow moonlight that came flooding down the walls. We wandered about after the squares and lanes had begun to be deserted, and stood for a long time admiring an old building against whose facade we made grotesque moon shadows. There was subdued conversation within doors, and the tinkle of a piano, and soon a woman’s voice singing. A cold spring breeze swept past us, carrying the fragrance of blossoming trees growing beyond the town limits. I do not know when it was, but at last we discovered that we were very sleepy and Miloš and I suffered Milada to guide us back to the inn.

Next day we went on to Horšice, which lay glistening and sun-drenched under the morning sky. Here we might have waited for a train, but a friend whom we acquired in the course of our ramblings urged us to make use of his horses and carriage, and so we were driven cross country to Králové Dvůr. From Králové Dvůr it was a short pilgrimage to Králové Hradec, and by this time we were such children of the road that we thought of buying tents or a house on wheels. But te voice of duty suddenly boomed into the ears of Miloš, from far Prague, and it came about that our excursion, like all good things, had an ending.

“Next time—” said Miloš, dreamily, while Milada, with a practical air, distributed to us hard-boiled eggs and black bread. “Next time we shall go south, eh? But where?”

“Next time, we shall do as we did this time,” said Milada. “We shall take the most convenient train. Take care, Miloš. You are scattering egg-shells about, and that is forbidden by the ministry of railroads.”

Of course, Miloš scoffed and said that this was not true, and while they were buzzing back and forth, I stared out of the open window and watched the cherry trees, shining and white, as if they had been dipped in a basin of soft snow.

![]()

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published in 1920, before the cutoff of January 1, 1930.

The longest-living author of this work died in 1977, so this work is in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 47 years or less. This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse