The Caribou Eskimos/Part 2/Chapter 1

I. Coast and Inland Population.

The Former Coast Population.

HOUSE RUINS. — It has been stated in the Descriptive Part that at several places along the coast of the Caribou Eskimo area there are ruins of permanent winter houses, a type of dwelling which the present population of these regions never use. These I have seen near the Hudson's Bay Company's post at Chesterfield Inlet (Igluligârjuk) and on Sentry Island (Arviaq); but according to the Eskimos there are also ruins at the following places[1]: Inugjivik and Iglulik near Fullerton; Depot Island (Pitiulâq); Silumiut between Depot Island and Chesterfield Inlet; Igluligjuaq on the north side of Chesterfield Inlet just opposite the above-named Igluligârjuk; Iviktôq south of Corbett Inlet; Qiqertarjuaq — which, in spite of its name, "the big island", is now actually a naze — south of Dawson Inlet; Ivik, south of Sentry Island and Eskimo Point, presumably at the mouth of McConnell River; and finally in the interior, Ikerahak, at Maguire River by the sledge trail from Hikoligjuaq to Sentry Island. Ellis mentions ruins from Marble Island[2].

The ruins at Chesterfield, which have previously been referred to by J. B. Tyrrell and Mgr. Turquetil[3], were partly excavated by Peter Freuchen, who found in them numerous relics which have been described in Therkel Mathiassen's archæological report.

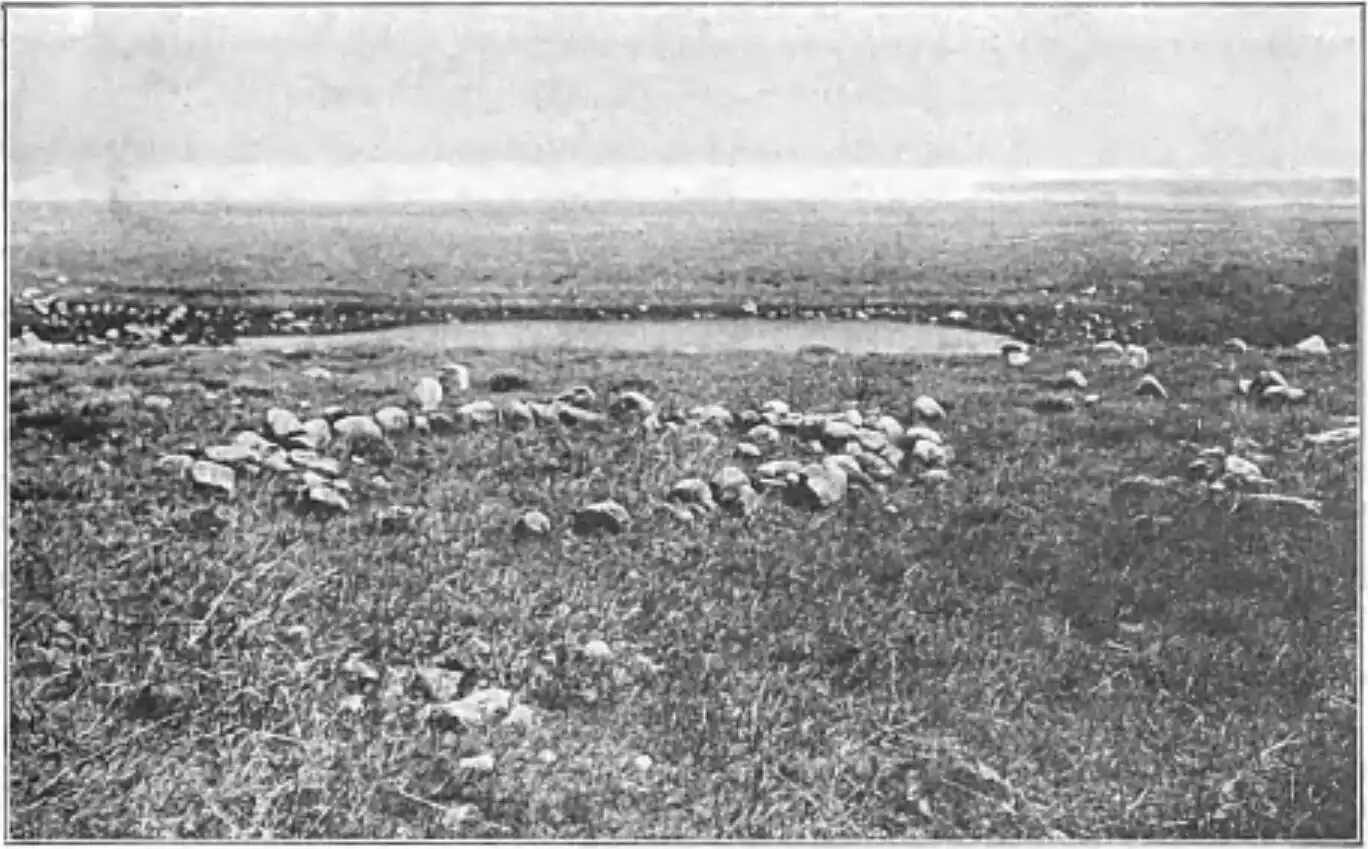

The ruins on Sentry Island are on the south side of the island. Three of them lie close together by the edge of a steep cliff 10 m. high, a little to the east of the highest point of the island; a little way to the east and rather lower down there is a fourth, big ruin. Sentry Island is an esker consisting of glaciofluvial sand, which is very unsuitable for preserving relics. By means of the examination which Jacob Olsen and I made of two of the ruins, we found a lot of very brittle seal and walrus bones, but no definite implements. Near the ruins there were many tent rings, cooking shelters, kayak supports, stone pillars for stretching seal thongs, graves, stone settings for play, some of them in the form of kayaks (fig. 1), and two big stone heaps which the Eskimos called cairns. At any rate most. of these remains lie some distance from the camping places that are now used on the island, but in such a position that their connection with the ruins is probable. The tent rings referred to here (fig. 2) are

Fig. 1.Stone settings in form of kayaks. Old settlement on Sentry Island.

distinctly different to the modern rings, which are much less solidly built.[4]

Fig. 1.Stone settings in form of kayaks. Old settlement on Sentry Island.

distinctly different to the modern rings, which are much less solidly built.[4]

The occurrence of these old settlements, with permanent winter houses, is nothing unique to the southwest coast of Hudson Bay. They are to be found along the whole of the coast of Roe's Welcome, Repulse Bay and Foxe Channel, on Southampton Island and in the regions about the Magnetic Pole.[5] As on Sentry Island, there is everywhere geological evidence of an uplift, which places the time of their habitation rather far back, and the relics found in the ruins clearly show that they belong to a culture that is connected with Alaska and Greenland but is sharply separated from the present Central Eskimo culture by the great part which the hunting of marine mammals has played; this culture is called the Thule Culture[6] from the place where it was first found in Greenland.

On these grounds alone it would not be unreasonable to assume that the ruins on the southwest coast of Hudson Bay, which stand under similar geological conditions to the ruins further away, date from the same old tribes as these, in other words that once upon a time there lived Eskimos at the coast with another culture than that of the present Caribou Eskimos. At any rate the very presence of the houses

Fig. 2.Tent ring of Thule type. Sentry Island.

is incontestible evidence that the former population, in contrast to the present one, lived at the coast in winter. And in fact several of the specimens excavated at Chesterfield present the peculiarities which mark the Thule Culture.[7] On the other hand it is not to be denied that Chesterfield lies so far out on the edge of the Caribou Eskimo area that this circumstance somewhat weakens the demonstrative power of the finds from there.

Fig. 2.Tent ring of Thule type. Sentry Island.

is incontestible evidence that the former population, in contrast to the present one, lived at the coast in winter. And in fact several of the specimens excavated at Chesterfield present the peculiarities which mark the Thule Culture.[7] On the other hand it is not to be denied that Chesterfield lies so far out on the edge of the Caribou Eskimo area that this circumstance somewhat weakens the demonstrative power of the finds from there.

Is it then possible to find support for our assumption through another channel? It is undoubtedly an argument in its favour that the coast group of the Caribou Eskimos consider the ruins to have been built by [tun·it], a legendary people whom the Iglulik, Netsilik and Copper Eskimos place in exactly the same relationship to the ruins within their respective areas.[8] In the interior, where there are no ruins, the Caribou Eskimos know nothing of the [tun·it]. There is, however, other and more direct evidence to which I will now turn.

Grave finds. On Sentry Island I acquired two complete grave finds which the local Eskimos had taken up before my arrival. I later on examined both the graves in question but without succeeding in throwing more light upon them.

The first find to be dealt with came from a grave on the highest part of the island. It is now entirely open at the top and the skeleton is therefore very much disturbed. It has apparently been at least partly covered with stones formerly, supported by at any rate two Image missingFig. 3.Adze handle. Sentry Island. wooden poles along the length of the grave; the poles were still visible among the stones. Among the human bones there were bones of seal and walrus; how they got there (possibly as presents of meat to the dead) cannot now be determined. The relics found are either purely a man's implements or of so neutral a character that at any rate they do not negative the presumption that this is a man's grave. It has once been a stately grave. The sledge has been left by it, presumably after having served to convey the body; there is a fragment of a cross slat. The drum has likewise followed the deceased to the other side, for pieces of both the ring and the drum stick have been preserved. The find also includes a snow beater of the usual form, a fragment of the wooden handle of a snow knife, a piece of a wooden bowl, the handle of a soup ladle of musk-ox horn; the shell of a mussel which has probably been used as a spoon, fragments of shafts of drills and arrows and finally the specimen which deserves special attention: a hammer shaped handle of antler, 24 cm long, with a step for a blade at the top and grooves for lashing on the underside of the head (P 20: 29; fig. 3).

Without doubt this is the handle of an adze. It is too small and slender for a pick. Nor does it seem feasible to call it a bone maul, as the handles of this kind of implement are always, I believe, furnished with a hole for a single lashing, corresponding to the comparatively short, heavy head. The blade of the adze, on the other hand, is often fastened on with two lashings which as a rule are passed through holes in the shaft; on one specimen from Iglulik and another from the Netsilik Eskimos in the Thule collection, however, the rearmost lashing is laid about a groove on a projection of the shaft as on the specimen here described. Neither picks, bone mauls, nor adzes occur in the culture of the present-day Caribou Eskimos; according to what the Eskimos themselves say the latter have, on the contrary, been in use earlier at the coast, but not in the interior. We will later on go further into this matter. For the present it is sufficient to state that this grave find by one example confirms the assumption that the earlier Eskimo culture at the coast was somewhat different to and, in certain directions, apparently richer than the present culture.

The other grave of those on Sentry Island to be referred to here was, like the first-mentioned, on the highest part of the island, approximately Image missingFig. 4.Grave find. Sentry Island. about 18 m above sea-level. By the grave lay a number of indeterminable pieces of wood, possibly the remains of a kayak, an icepick of iron, and some walrus bones. Prior to my arrival the Eskimos had removed the grave goods, which comprise the following specimens:

P 20: 6. Harpoon head of antler, thin, with powerful ventral and dorsal barbs and bifurcated dorsal spur (fig. 4 c). At the fore end a blade groove with a drilled rivet hole and traces of rust, at right angles to the line hole which runs directly from side to side. The shaft socket open on the left side; in each of its edges are three lashing holes connected by grooves for the lashing. Length 8.9 cm.

P 20: 7. Harpoon head of antler, thin, no barbs but with dorsal spur (fig. 4b). At the fore end a blade groove, but neither rivet hole nor marks of a blade. The line hole direct from side to side. Closed shaft socket. Length 9 cm. It is probable that this head has never been used.

P20: 8. Harpoon head of antler, the same type as the foregoing. Remnant of iron blade in a groove which is at right angles to the line. hole. The line hole and the shaft socket very small. Length 9 cm.

P 20: 9. Harpoon head of antler. Breadth and thickness almost the same; rounded belly with openings for the line hole (fig 4 a). The blade groove parallel to it, with rivet hole and traces of iron blade. At the rear two lateral spurs, of which the right one has been broken in use. Rivets and lashing holes show how it has been repaired. Length 6.1 cm. Shape and size mostly indicate that it has been used for ice-hunting.

P 20: 10. Ice pick for a harpoon shaft, of antler (fig. 4 e). In one edge a distinct step, in front of which is a lashing hole. Length 20.5 cm.

P 20: 11. Side prong of a bird dart, of ivory (fig. 4 f). Two inturned barbs, at the rear a scarf face, two lashing holes and an outturned heel. Length 17.5 cm.

P 20: 12. Weapon point of ivory, presumably the middle prong of a bird dart (fig. 4 g). Round, lanceolate at the fore end, the rear end broken off. On one side two, on the other side seven small barbs. Length 16.8 cm.

P 20: 13. Barb for a leister prong, of antler (fig. 4 h). At the rear two lashing holes, a scarf face on the inner side and a groove for the lashing on the outer side. Length 13.1 cm.

P 20: 14. Point of antler, round at the fore end, square in section at the rear (fig. 4 d). Where the round and the square sections meet is a small step on one side and, in front of this, a narrow hole through the specimen. Length 11.6 cm. Perhaps the middle prong of a leister; it seems to be too slender to be a foreshaft for an ice-hunting harpoon.

P 20: 15. Roughly formed knife handle of antler; at the fore end a hole with remnants of the tang of the iron blade. Length 13.3 cm.

P 20: 16. Small fragment of an arrow foreshaft, of antler. At the fore end signs of a blade groove (no rivet hole) and a long, close barb on one side. Length 6 cm.

P 20: 17–18. Three flat pieces of bone: one with a roughly sharpened point; one with blade groove and bored rivet hole; one with blade groove without rivet hole, but with a hole through from side to side further back. Lengths 14.4, 15.6 and 13.5 cm respectively.

P 20: 21. Two fragments of wood of the same weapon shaft, with hollows in each end. Total length about 146 cm.

P 20: 19. Piece of antler, very slightly worked. Length 14 cm.

There is no reason for doubting that all these relics really belong to the same grave. As far as can be determined, they are all men's implements and mostly hunting implements. The presence of the bird dart, which has now entirely disappeared from among the Caribou Eskimos, is of interest. The most important of all the specimens is, however, the harpoon head first described. This type — with or without blade — is one of the most characteristic forms of the Thule Culture,[9] whereas it is now never used by any Central Eskimo tribe. That it is not an old specimen which has accidentally come in among younger objects appears from the fact that it has had an iron blade. It thus seems that a form of culture which was not only richer in. elements than the present one, but which also had a certain continuity with the Thule Culture, existed on the west coast of Hudson Bay in such recent times that the Eskimos had easy access to iron. This period can hardly be put at earlier than the first half of the 18th century.

Early writers on the Hudson Bay Eskimos in the 18th century. Under these circumstances it will be natural at this point to bring together the early information which, according to its nature, has been scattered in the Descriptive Part of this work. In doing so we cannot help noticing that in the eighteenth century there was apparently a much more extensive hunting of bowhead. whales, especially at Whale Cove,[10] and it seems that the implement used was a whaling harpoon of the common Eskimo type with a float of sealskin.[11] It is quite in conformity with this that the Hudson's Bay Company's sloop, on its trading trips north of Churchill, bought up baleen, walrus tusks and sealskin from the Eskimos.[12] When Knight's crew on their unfortunate expedition wintered on Marble Island, the Eskimos sold them whale blubber,[13] and they themselves preserved the various foodstuffs with blubber in bags of sealskin.[14]

None of the Coast Eskimos today know anything of whaling or preserving with blubber, and, what is more, they confidently assert that their forefathers did not know it either. The same people who, as in Greenland, have faithfully preserved the names of the last Norsemen and whose traditions display the most astonishing conformity from the Pacific to the Atlantic, would not have forgotten it if, only 150 or 200 years ago, they had lived in another manner than they do now.

Similar observations as with regard to mode of living can be made concerning the use of the umiak. Ellis' remarks cannot very well be understood otherwise than that in his time the umiak was in use on the southwest coast of Hudson Bay,[15] which by the way is quite reasonable, as it is just in whaling that it is mostly used. Ellis has noticed a small but characteristic difference from the present-day Eskimos when he writes that animal teeth were worn as a sort of beading or fringe along the edge of the frock.[16] Mention must also. be made of Dobbs' statement regarding the occurrence of baleen nets,[17] though it is possible that this applies to the coast between Chesterfield and Wager Inlet, north of the area of the Caribou Eskimos.

Now the fact is that the extensive hunting of aquatic mammals, and particularly whaling, is just characteristic of the Thule Culture,[18] and very probably this also applies to the baleen net; Mathiassen's reservation with regard to this latter question seems rather exaggerated,[19] even though it is admitted that there is no absolutely definite proof of the tenability of the view here expressed. The umìak, as has just been said, is so closely associated with whaling that it may with the greatest probability be placed to the same culture complex,[20] and finally, as regards the use of pierced animals teeth as fringing on the dress, this is general in southern Baffin Land and in Labrador,[21] two localities which have preserved many of the peculiar features of the Thule Culture.[22]

Thus we have to reckon with the following facts: (1) that along the southwest coast of Hudson Bay there are house ruins of unquestionably Thule type, which show that once, in contrast to the present time, Eskimos have lived by the coast in winter too; (2) that, according to the conforming evidence of the grave finds and the written records, a culture prevailed in the same localities in the eighteenth century which, in some respects, was more richly equipped than the present culture and, on certain points, agreed with the Thule Culture. Nothing is then more reasonable than that we have to deal with a branch — undoubtedly a changed branch in many respects — of this old culture.

Although the origin of the Thule Culture certainly dates very far back, as is shown by the situation of many of the ruins, there is nothing remarkable in its having lasted so long here. The culture on Southampton Island, which only disappeared with the extinction of the Sadlermiut in 1902–03, was a direct branch of the Thule Culture. The question now is whether the Eskimos who in our day live by the southwest coast of Hudson Bay are descendants of the carriers of the Thule Culture in the eighteenth century. We will consider this matter in the following.

Inland elements in the culture of the Coast Eskimos. The Caribou aver, as already stated, that they have never known whaling and the umiak. Negative evidence of this sort, however, is only of slight value if it is not supported by positive evidence. But among the Pâdlimiut both in the interior and at the coast there is a certain tradition that the latter originally came from the interior, and this is confirmed by a number of important elements in their culture.

It has several times already been emphasised that even the bands of Caribou Eskimos who regularly go to the coast of Hudson Bay cannot be called coast people in the same sense as their kinsmen in other places, not even so much as their neighbours the Iglulik and Netsilik groups, who are by no means so closely associated with the sea as most of the Alaskan Eskimos and the Greenlanders. Apart from two or three Qaernermiut families, they only come down to the coast for two summer months, and consequently such an important hunting method as breathing-hole hunting cannot be practised. Every form of whaling, even of small whales, is unknown.

The slight familiarity with the sea which is reflected in this circumstance is observable in many ways in their culture, in both large and small matters. The most important is probably that the Coast Pâdlimiut never use blubber as fuel for cooking, but even out by the coast only use heather. Sometimes the Hauneqtôrmiut cook over the blubber lamp, but not so frequently as other Eskimos. It is also of importance that the Coast Pâdlimiut quite lack the exactly laid down rules according to which other Eskimos share out aquatic mammals, and that when the kayak was still in use at the coast, they often covered them with deerskin instead of sealskin. Their taboo regulations regarding the aquatic mammals are of much simpler kind than those which we find among the Iglulik and the Netsilik groups. It is even worth mentioning such small features as the fact that they do not understand how to soften dry sealskin in a proper manner and that they never eat the meat of aquatic mammals when it is rotten, although they eat putrid caribou meat with much relish.

All these circumstances, in connection with the tradition just inentioned, may presumably only be interpreted in one manner, viz. that the present coast population has only recently come down to the coast and has not yet learned to adapt itself to the new mode of living. There must have been a change of culture in these areas, the Thule Culture having fallen into disuse and another form having been brought into the foreground.[23]

Time and causes of the change of culture. It is clear that the aforementioned offshoot of the Thule Culture on the southwest coast of Hudson Bay remained alive until the beginning of the eighteenth century. This appears both from the old records and the presence of iron together with a relic such as the harpoon head of the Thule type which has been described. On the other hand it does not directly appear from any source when whaling by the Eskimos in these areas ceased. There is nothing to indicate that it was continued into the nineteenth century. Franklin, Richardson, and Rae were accompanied by Eskimo interpreters from the coast north of Churchill, and one might certainly have expected that in some way or other these Eskimos would have referred to whaling in their country if there had been any. On the other hand, one may not venture to attach too much importance to the fact that writers from the end of the eighteenth century, like Hearne and Umfreville, refer to matters which have to do with the old aquatic mammal culture, as both these writers sojourned at Hudson Bay for many years before their books appeared. The tradition of an emigration to the sea which is still preserved among the Pâdlimiut puts it some generations, but not many, back in time. The one circumstance with the other justifies us in directing special attention to the latter half of the eighteenth century, and in that very period an event took place which doubtless may be placed in connection with the matter here discussed: the penetration of the Chipewyan over the southern Barren Grounds to Churchill.

The indirect cause of this, as of so many North American migrations of people, was the European colonisation which, like a stone that is thrown into the water, sets the ripples in motion to all sides. A powerful impulse everywhere was the acquisition of firearms, which made a tribe superior to the neighbours who lived further out on the periphery.

In this manner the Cree, who as early as 1668 visited Lake Superior and soon afterwards also came on trading journeys to Sault Ste. Marie and Mackinac,[24] were enabled to penetrate far to the west at the expense of the Athapaskan tribes. The Beaver and Slavey were driven from lower Peace River; the former went up the river, whilst the latter made their way down along it from Lake of the Hills, to be later on forced away from Slave River and Great Slave Lake to their present area west and northwest of the latter lake.[25] In 1718 the Chipewyan still lived at Peace River; but after having thrown off the attack of the Cree, they placed themselves in possession of the former hunting grounds of the Slavey; while one band settled about Lake La Crosse and upper Churchill River, the then recently established Fort Prince of Wales attracted the group which is known as Etthen-eldeli, or Caribou Eaters, out towards Hudson Bay.[26] Under the shelter of the walls of the fort they had no need to fear the attacks of the Cree and were able to trade in peace.

For the time being, however, they could not settle down as they have now done at the very mouth of Churchill River, which from ancient times has been a part of the Cree territory.[27] Even as recent an author as Coats says that this territory stretched as far north as to Seal River.[28] Under these circumstances the Etthen-eldeli had to keep to the edge of the forest and the Barren Grounds; for this reason Coats says that the Chipewyan only come to Churchill to trade every other year from a land by "a lake or sea" which is separated from Seal River by a portage.[29] Mackenzie says that the Chipewyan regard the Barren Grounds, and not the forests, as their "native country".[30] Only gradually has Churchill become the boundary between the Chipewyan and Cree, and the latter have now withdrawn from there entirely. When I visited Churchill in 1923 there were only two Cree women, wife and mother-in-law of one of the halfbreeds in the service of the Hudson's Bay Company, and at any rate the elder of the two women had come there from Trout Lake.

Cut off from the south from the first, the Chipewyan apparently took the whole of the southern Barren Grounds into possession during their advance. How far north they extended their hunting trips cannot be decided. Hearne has them going right up to lat. 68° N.;[31] but this is undoubtedly greatly exaggerated. In a letter dated 28th June 1742 to Sir Charles Wager Captain Middleton, however, writes: "Two of these Indians . . . . . . have, as far as I can understand, been at Ne Ultra (i. e. Roe's Welcome)" and in a letter of 2nd October the same year he says that Marble Island is "not far from their country".[32] When Captain Scroggs discovered Cape Fullerton in 1722, one of his Chipewyan companions wanted to leave the ship "saying he was within three or four Days Journey of his own Country"; this, however, may be due to a misunderstanding, so much the more as on the same voyage Eskimos were met with at the coast in lat. 62° N..[33] Later on when the H. B. C. sloop came to Dawson Inlet, however, they traded not only with the Eskimos but also with Chipewyan.[34]

Having regard to the hostile feelings of the Chipewyan and Eskimos for each other we may suppose that the Indian occupation of the southern Barren Grounds did not proceed peacefully. An historically known example of war is given by Hearne, who relates that in 1756 the Chipewyan massacred the Eskimos at Dawson Inlet.[35] After this, many years passed before the Eskimos dared show themselves in the vicinity of the Indians. There can hardly be any doubt that about the middle of the eighteenth century the Eskimos were the victims of constant attacks in which, in the absence of firearms, they necessarily drew the shortest straw, and that through this they were gradually driven northwards from their old settlements. It is significant that Hearne was able to make his journey east and north about Hikoligjuaq, right up to the vicinity of Dubawnt River and back to Churchill, without meeting Eskimos. They must have left the field, perhaps as far as to Chesterfield Inlet and Baker Lake, to the Chipewyan; but if this is the case, there is a very great possibility that in this we have the reason for the simultaneous disappearance of the aquatic mammal culture from the southwest coast of Hudson Bay.

Since then the expansion of the Chipewyan has ceased, perhaps because the Eskimos in their turn were gradually provided with firearms, perhaps for other reasons, as for instance the cessation of the pressure of the Cree in the south. When the Chipewyan retired towards the timber line, the Eskimos seem to have followed on their heels; these new immigrants, however, mostly came from the interior and the old aquatic mammal culture at the coast was never really revived again.

Special features of the coast culture: Geographically conditioned elements. If the changes in people and culture on the Barren Grounds have proceeded in the manner here assumed, we cannot get away from the fact that they have been connected with an even considerable supply of new blood to the coast population. On the other hand we must take care not to imagine the events as being a sudden break with the past, a total revolution. The offshoot from the Thule Culture, the existence of which is presumed to have been proved in these areas in the eighteenth century, was even then a pure Thule Culture no longer. A harpoon head such as the broad form, with the openings of the line hole on the belly, and the leister barb with a groove for the lashing, but with no "neck", both described from Sentry Island, occur in the Thule Culture it is true, but are not very typical, and the harpoon head at any rate is a late form.[36] The side prong of a bird dart from the same find is different to the Thule type, which always has barbs on both the outer and the inner side.[37] The gap between the eighteenth century coast dwellers and their successors was certainly smaller than it would have been if the genuine, old Thule Culture had still flourished.

Therefore it is natural to ask whether among the present coast population there are not features which also descend from their predecessors. This leads to an all-round consideration of the elements which the coast culture includes but which the culture in the interior does not. It must be taken for granted that they have either been adopted from the earlier coast dwellers or borrowed from neighbouring tribes. An independent development is quite out of the question, having regard to the short period which has been available and the great similarity which these elements display to those of other Eskimos.

Thus first of all we meet with a group of elements whose existence is directly the result of geographical conditions, inasmuch as their very nature precludes their presence in the interior but represents an adaptation to life at the coast. These elements are: All methods for the hunting of seal and walrus (from kayak, ice-edge, breathing-hole, and the hunting of basking seals on the ice) as well as the appurtenant implements (bladder dart and ice-hunting harpoon with toggle head, drag, loose lance head, wound plugs, breathing-hole searcher and seal indicator). To these, however, are connected a number of elements which certainly are not so much the result of geographical conditions as the others, but yet are most closely associated with life at the coast, viz. the curing of hairless sealskin by souring with blubber,[38] the manufacturing of seal thongs and the use of the blubber lamp, which again means lamp trimmers, drying racks and blubber trays.

As regards breathing-hole hunting and its implements, the breathing-hole searcher and seal indicator, matters seem to be quite clear. They demand sojourn at the coast in winter, and only a few Qaernermiut families live in this fashion. Their own tradition says that they only began to spend the winter at the coast when the American whalers came there after 1860. At the same time they came into close contact with the Aivilingmiut and, as the Qaernermiut methods and implements for breathing-hole hunting are indentical in every way with those of this tribe, it seems out of the question that they can have obtained them from anywhere else than just from the Aivilingmiut.

The case of the other elements concerning aquatic mammal hunting is more difficult. Apparently they may just as well have come from: the former coast dwellers as from their neighbours. The commonly used form of harpoon head — thin, no barbs, closed shaft socket, dorsal spurs and the blade parallel or at right-angles to the line hole — occurs in the Thule Culture, but is also common among the present-day Aivilik and Iglulik Eskimos.[39] Among the Eskimos the loose lance head has a diffusion that is limited to Hudson Bay and the areas to the east of it; the Thule type of this weapon has an open shaft socket, whereas the present coast dwellers and the Iglulik Eskimos use closed sockets; but from Southampton Island there is a transitional form,[40] which makes it possible that the closed socket was already known to the earlier coast population on the southwest coast of Hudson Bay. The drag has a diffusion to the east which resembles that of the loose lance head, it being known from West Greenland,[41] the Polar Eskimos,[42] Labrador and Baffin Land,[43] the Iglulik Eskimos[44] and Southampton Island.[45] According to its nature it is not surprising that we have no direct evidence of its occurrence in the Thule Culture; but on the other hand its occurrence among the Polar and Southampton Eskimos points in that direction and therefore the question of whence the Caribou Eskimos received this element cannot be settled. As to the wound plug, nothing can be said.

The blubber lamp has not the typical Thule form with a row of knobs along the front rim, and in this it resembles the lamp of the present-day Aivilingmiut. On the other hand the contrary is the case with its proportions. Mathiassen has shown[46] that the proportion between length and breadth of the lamp of the Iglulik group is nearly always a little higher than 2, whereas for the lamps of the Thule Culture it is about 1.7. For three lamps of the Caribou Eskimos measured it varies between 1.63 and 1.76. It is hardly probable that they would have altered the proportions if they had acquired the lamp from their neighbours, and it is especially improbable that they would have altered them to exactly the old value, and it must therefore be assumed that the lamp is a heritage from the earlier coast population who presumably already had abandoned the row of knobs along the rim. The lamp trimmer is so closely attached to the lamp that its origin is most probably the same as that of the lamp. The same perhaps applies to the drying rack; so far, however, this has not been definitely recognised in the Thule Culture, although it has undoubtedly been present.

The blubber tray with sides of thin wood bent round a separate bottom like that of the Caribou Eskimos, is used by the Aivilingmiut, and similar vessels are known from the Thule Culture, with wooden bottom and sides of baleen.[47] The use of another material in the Thule Culture need not, however, mean that the Caribou Eskimos have used the vessel of the Aivilingmiut as a model, as the use of baleen of course is dependent upon whaling. In reality, nothing can be said with certainty.

It is just as difficult to decide whence the Caribou Eskimos have learned the making of seal thong. Like the Aivilingmiut (but contrary to the Polar Eskimos), they stretch the thong while it is drying; but on Sentry Island near the ruins there were small stone cairns for this purpose, which shows that the old coast dwellers have employed the same method. Blubber-soured skin is known for instance from Southampton Island[48] and from the Polar Eskimos, which may indicate that it was also known to the people of the Thule Culture. The Aivilingmiut use a similar method,[49] and thus in this case too it is not possible to say anything of the origin of the method of the Caribou Eskimos.

Special features of the coast culture: Substitutional elements. In contrast to the geographically conditioned elements there is a group which simply represents substitutions of forms which also occur in the interior. This group comprises the tent of the ridge type, dog harness with parallel loops, arrows with barbs and three radial feathers, needle-and-thread tattooing, and closed stone graves.

The Eskimo tents comprise three main types: domical, conical and ridged. Sarfert considers this order to be a sequence of development resulting from a lack of suitable material in the Arctic.[50] Mathiassen does not express any opinion as to genetic connection, but agrees in so far with Sarfert that he assumes that the conical tent has been chronologically replaced by the ridge tent.[51] The conical tent he considers belonged to the Thule Culture but had never reached Greenland, and in the Central regions the shortage of wood had caused the adoption of other forms. If this were correct, the question of the ridge form among the Caribou Eskimos would almost answer itself; in all probability it must have been borrowed from the Aivilingmiut, and this would be so much the more probable as Hearne refers to "circular" — i. e. presumably conical — tents among the old coast population at Hudson Bay.

But the question is not answered so directly. It is not very probable that Sarfert's order really represents a sequence of development. This opinion hangs together with the whole of his view which, in the dwelling, principally sees a function of the geographical surroundings. In reality, the Eskimo forms can scarcely be explained from conditions of nature alone, for they obviously are related to corresponding types in other parts of North America and Eurasia.

Even if Sarfert's hypothesis of development is wrong, Mathiassen's views regarding the chronological sequence might of course be correct enough. But this, too, seems rather improbable. The ascribing of the conical tent to the Thule culture is supported on a very slender foundation. Only two arguments are presented: (1) the purely negative one, that none of the easily recognisable cross poles of certain ridge tents have been found, and (2) a picture of two conical tents on a comb from Southampton Island. A negative argument does not mean much, of course, especially as some undoubted ridge tents (Coronation Gulf, southern Baffin Land and Labrador) lack the particular cross pole which Mathiassen has in mind. Thus it is the last point to which we must hold. In the first place it must be observed that the circumstances of the finding of the comb are uncertain.[52] The specimen was found and brought in by the Eskimos and, even though its shape matches that of the Thule type, this does not mean that it actually dates from the time of the old Thule Culture itself. It is more important, however, that tents like those pictured on the comb are not known at all from the Eskimos. They have a number of very long poles, a sheet which is either wound in a spiral round the frame or consists of several pieces, and it seems as if there were a smoke hole in the top. The spirally-wound or pieced tent sheet occurs in the west,[53] but not among the Central Eskimos who, for their conical tents, use a continuous, semi-circular sheet. Long poles, which project above the tent sheet, are on the other hand only used by the Central tribes (but never so long as those pictured), whereas the western tents have short poles, and the tent sheet has two "pockets" in the top to take the poles. Finally, no Eskimo tent has ever been furnished with a smoke hole.

The result of all this is that the tents pictured on the comb give a much more Indian than Eskimo impression. The long poles, the pieced or spirally-wound sheet and the smoke hole are to be found on all the tents of the two tribes which in this respect are principally concerned, viz. the Chipewyan and Cree.[54] This would indicate that the tents pictured do not represent Eskimo tents at all, but Indian, and this is explainable when we remember the aforementioned great advance of the Chipewyan over the southern Barren Grounds. The place where Southampton Island has easiest access to the mainland is the southwest corner opposite Cape Fullerton, i. e. the very region where there was most possibility of meeting with Indians.

If we would attempt to determine the relative ages of the conical and ridge tents among the Eskimos, it is not sufficient to consider this people alone. Hatt has previously stated that, on account of the diffusion of these particular types, he regards the ridge tent as being the elder in the circumpolar region[55] and, with particular reference to California, Krause has also come to the conclusion that the conical tent is a late form.[56] A closer examination of the distribution of the types will confirm these assumptions. In sub-arctic Canada among the Beaver,[57] Chipewyan (?) and Cree,[58] simple wind screens of the ridge type are used as temporary travelling shelters, whereas the conical tent is the dwelling proper, and from the Beothuk on Newfoundland there is a record of an actual ridge tent as a store room.[59] The temporary use of wind screens is also known from the Northwest Indians,[60] the northern plains,[61] California[62] and the Southwest.[63] On the other hand, permanent dwellings of the ridge type only occur in two regions in North America, both of which in many directions are outstanding in that they have retained old features: the North Pacific plateaux and California. There they are to be found among several Athapaskan. Salishan and Shahaptin tribes[64] and, as regards California and South Oregon, among the Yokut, Pomo and Gallinomero as well as some Karok, Yurok and Takelma in conjunction with pits.[65]

Turning to Eurasia, we also meet the screen or ridge type as a temporary shelter over most of the sub-arctic region along with the conical tent and other more permanent dwellings: among the Yakut,[66] several Tungusian tribes in the Amur area,[67] and all the Finnish-Ugrian peoples.[68] Finally, it is the actual dwelling among some Amur tribes[69] and on the great Central Asiatic plateaux among the Tibetans and Tangut.[70] In conjunction with pits this ancient type is also to be found among the Ainu on Sakhalin[71] and even among the Japanese pariahs or Eta.[72]

This summary, which does not claim to be complete, serves to confirm the correctness of Hatt's theory. We only find the ridge type as a permanent dwelling on the outskirts of the boreal region or in places which, on account of their inhospitable natural conditions and comparative inaccessibility, must be regarded as a kind of "cultural resistance regions" (the northwestern plateaux in North America). In the intermediate regions it occurs as a temporary shelter on journeys and hunting trips, whereas otherwise it has been replaced by other types and, most of all, by the conical tent which thus reveals itself as being younger.

But this does not prove that this sequence, even if on the whole it is correct, also holds good in an isolated case as among the Eskimos. At the most it can give but a valuable indication. In the following chapter, however, I will go further into the occurrence of the conical tent and, I believe, prove its late appearance among the Eskimos. For the present our considerations will be restricted to the ridge tent, of which there are several forms among these people and the mutual connection between which has not yet been elucidated in all details, but in the main is incontrovertible. It then appears that the diffusion of the ridge tent decidedly indicates a considerable age in this case too. As Table A 3 shows, it is almost predominant in Greenland, Labrador and Baffin Land. By the Northwest Passage it is as yet as common as the conical tent, but then it disappears in Alaska. On the other hand it appears again as a temporary travelling shelter among the Aleut and the Chukchi. If the later hypothesis of the late appearance of the conical tent in Alaska and the Central regions is correct, it is justifiable to regard this ridge form in the west as being genetically connected with the types in the east.

It is, however, characteristic of the elements of the Thule Culture that they connect the eastern and western Eskimo areas so to say beneath the culture layer which is now prevalent in the Central area. In many cases where an element cannot be shown archæologically an area of distribution interrupted in the middle will just therefore be the only means of recognising it as a Thule type. We have such a case before us now, and probable the ridge tent must be regarded as the particular tent form of the Thule Culture.

To return at last to the starting point of this discussion, this in reality does away with every possibility of deciding whether the ridge. tent has been absorbed into the culture of the Caribou Eskimos from the old coast dwellers or from the Aivilingmiut; for it need not be specially emphasised that Hearne's mention of "circular" tents at Hudson Bay means nothing in this connection, as he does not say whether they were the only form known.

From the tent we turn to the dog harness. Harness with parallel loops is used by the Iglulik Eskimos;[73] a similar harness was, however, found on Southampton Island, which was a particular place of refuge of the Thule Culture in Hudson Bay. Its distribution, which is shown on Table A 44, also indicates that it is a Thule type, its principal diffusion falling into an easterly and a westerly part, whereas the harness with crossed loops to some degree contests its position in the Central areas. Thus it may very well have been present in the offshoot of the Thule Culture on the southwest coast of Hudson Bay, and it cannot therefore be decided whether the present Caribou Eskimos received it from their predecessors or from the north.

Table A 22 shows that arrows with three radial feathers have a comparatively small distribution among the Eskimos, at any rate among the eastern tribes who nearly always use two tangential feathers. This is, for instance, the case with the Iglulik group. The only arrows known from Southampton Island have three radial feathers, however, and therefore it is not impossible that this type may have been known to the old coast population at Hudson Bay. Both forms of feathering occur among the Netsilik tribes and there is thus a possibility that the Caribou Eskimos may have the three-feather type from them. Still, this is not very probable, as it seems to be restricted to the coast, i. e. that part of the Caribou Eskimo area which is farthest from that of the Netsilik Eskimos. The three feathers are thus more likely to be a heritage from the earlier coast dwellers; this is no more than a supposition, however.

Something similar may be applied to barbed arrow-heads of antler (cf. Table A 21). They are common in finds from the Thule Culture, especially the oldest of these, and are still used by the Netsilik tribes, whereas the present Iglulik Eskimo arrows are never barbed.

If we look at Table A 64 of the diffusion of the methods of tattooing, we will observe that needle-and-thread tattooing prevails in two areas: to the east in Greenland south of Melville Bay and to the west in the area from the Mackenzie Delta to South Alaska. In addition, this method is found side by side with the pricking method among the Iglulik group and in southern Baffin Land; although it is not expressly mentioned from Labrador, there is a possibility that it is also known in this little explored area, as the people on both sides of the Hudson Strait very closely resemble each other. This diffusion speaks decidedly in favour of the needle-and-thread tattooing belonging to the Thule Culture, and there is a further confirmation of this in the distribution of this method in the rest of North America, which clearly discloses it as having come from Asia (cf. Table B 43). Presumably it is an inheritance from the Thule Culture to both the tribes of the Iglulik group and the Caribou Eskimos by the coast.

The occurrence of the closed stone grave (cf. Table A 111) has in recent times been touched upon by König[74] and, although he does not go into detail, he has apparently to a certain extent been on the right track. Since then Mathiassen has taken the question up and with great probability shown that the closed grave belongs to the Thule Culture.[75] Of course there is no reason to believe that the Caribou Eskimos at the coast have adopted the closed grave from the Aivilingmiut, who themselves regard it as being characteristic of a foreign people. Presumably it is the former inhabitants of the coast area at Hudson Bay who have handed it down to their successors.

Special features of the coast culture: Augmenting elements. Besides the elements which either signify a geographical adaption or take the place of types which are known in the interior, there is in the coast culture a group which, without being geographically conditioned in any way, signifies a simple augmentation. It comprises trace buckles, tower traps (?), gull hooks, bolas, eye shades, glue (?), adzes and needle cases.

Trace buckles are commonly used by the Iglulik group and are also known from Southampton Island,[76] the Netsilik Eskimos and others. Mathiassen's excavations have shown that a similar, though more slender, type was known in the Thule Culture.[77] The only specimen we have from the Caribou Eskimos perhaps resembles certain Iglulik buckles as much as the Thule type, so that there is a possibility of a borrowing from the north. Yet the material at hand is so small, and the difference between the forms so slight when one has not long series to go upon, that nothing certain can be said.

Tower traps seem to belong to the Thule Culture.[78] Mathiassen refers to them at Repulse Bay and Southampton Island,[79] the Iglulik Eskimos, Nottingham Island, Willersted Lake on Boothia Isthmus, the Polar Eskimos, West Greenland and Northeast Greenland. He furthermore supposes — quite justifiably I believe — that some stone erections which Stefánsson and Jenness describe from Coronation Gulf are also tower traps. To these occurrences may be added the west side of Roe's Welcome and the previously mentioned "tower" on the north shore of Baker Lake. The “ruin" of a conical building which Sherard Osborn found on Cornwallis Island[80] must presumably be regarded as a tower trap too. They also occur in Labrador,[81] and in Baffin Land the Eskimos build traps of ice on exactly the same. principle.[82] It is true, as Mathiassen says, that there is no record of their use among the Western Eskimos; possibly, however, this is merely due to accident, as the Chukchi build a kind of tower trap of snow.[83] Thus this type seems to have had a wide diffusion in earlier times. It is hardly possible to say where the Caribou Eskimos got it from. If it is correct that only the Qaernermiut know it, this might indicate an adoption from the north; but it is by no means certain.[84]

The gull hook is really identical with the gorge for salmon; it is only its use for birds that is peculiar to the coast people. From the Thule Culture we know of a specialised form with a cross-pin, which is diffused from Wager Inlet to Îta (Etah) in North Greenland and has also been used in more recent times by both the Iglulik and the Southampton Eskimos.[85] Mathiassen is undoubtedly correct in regarding the more simple type, consisting only of a bone pointed at both ends, as being the elder; besides from finds from King William's Land and Ponds Inlet, he mentions it from West and East Greenland, Point Barrow and Norton Sound. This may however be supplemented by Labrador,[86] the present-day Netsilik Eskimos[87] and the Chukchi.[88] It is obvious that one cannot say anything as to where the Caribou Eskimos at the coast got this implement from.

The bola is common in finds from the Thule Culture and Mathiassen also refers to it from West Greenland (as a toy), Southampton Island, Back River, the Mackenzie area, North Alaska and East Cape.[89] To this may be added the Aleut,[90] the Chukchi[91] and, as a sling-shot with a single ball, the Koryak.[92] On this foundation Mathiassen regards the bola as being “an old culture element common to all Eskimos". Having regard to the extremely sparse and scattered occurrence of this implement in the Central areas I prefer to express it thus: that the bola belongs to the Thule Culture, but at Back River and the southwest coast of Hudson Bay it has descended to the later inhabitants.

Eye shades do not occur in finds from the Thule Culture; but they have a diffusion which makes it probable that they belong to it. As Table A 67 shows, they have a main area towards the east in Greenland, southern Baffin Land, in a possibly degenerate form on Southampton Island where wood is scarce, and among the Caribou Eskimos at the coast. The specimen shown in the Table from the Netsilik Eskimos (King William's Land) is doubtful; it is of light coloured skin and ornamented with dark strips drawn through it and is perhaps only a brow band.[93] On the other hand we find a new main area for the eye shade farthest west on both sides of the Bering Sea. As in addition the eye shade is not known to the present-day Iglulik Eskimos, it is hardly to be doubted that the Caribou Eskimos have taken it from their predecessors.

Glue made of blood is known in West Greenland[94] and is also mentioned from Baffin Land,[95] the Iglulik Eskimos,[96] the Netsilik group,[97] the Copper Eskimos,[98] and the Mackenzie region.[99] In Alaska. glue is made from congealed train-oil, fir-resin etc.,[100] whilst the Aleut use fish-glue.[101] This diffusion does not contribute towards elucidating the question of where the Caribou Eskimos learned to know glue; but the circumstance that its use seems to be restricted to the Qaernermiut would mostly indicate that it has immigrated from the north.

The adze is an implement which in several respects presents unsolved problems. It has gone out of use among the Angmagssalik and Polar Eskimos and its occurrence in Labrador is doubtful.[102] It is not very common among the present-day Central Eskimos, and Jochelson emphasises its scarcity among the Aleut.[103] Finally, the adze among the Pacific Eskimos is of a type that is fundamentally different to that of the other tribes, much heavier, made by pecking crystalline rock, and furnished with a groove for lashing; it closely approaches the prevailing type among the Northwest Indians. Although we know that the adze occurs in the Thule Culture, it is, under these circumstances, impossible to decide whether among the Caribou Eskimos it represents a new acquisition to the coast group and, if so, where it was borrowed from, or whether, on the other hand, its absence in the interior is due to its having fallen into disuse as is the case in some few other places.

Nor does the diffusion of the adze in North America outside the Eskimo area and in North Asia seem to give any hint as to whether it was originally an implement common to all Eskimos or not. Apart from the Pacific type, the stone blade on the Eskimo adzes is polished, has no lashing groove, and as a rule is intended to be inserted in a head of antler or the like; often it is small and rather crudely finished. Some blades, however, are larger and placed directly on the shaft. In the Columbia-Fraser River area, adze heads of antler have been found with small stone blades which very much resemble those of the Eskimos,[104] and a small, polished, rather flat celt like Hc 250, CNM, from Sitka, has possibly also been set in an intermediate piece; at any rate it differs considerably from the heavy grooved adze blades which are prevalent on the North Pacific coast. But even though certain blades from this area may resemble Eskimo adze blades, and even though they have been set in an intermediate piece, the shafting need not always have been like that of the Eskimos. This is to be seen from two axe handles of antler, Hc 106 a and b, CNM, from the Knaiakhotana. On these the intermediate piece is a natural prong of the handle and thus essentially different to the Eskimo type — in reality there is much greater likeness to the few axe handles which are thought to represent Denmark's earliest Stone Age, whereas the Eskimo type more resembles the presumably younger axe heads of the Mullerup Period, apart from the fact that the latter have a shaft hole.

In eastern North America it is again the problem of shafting which causes difficulty in the comparison with the Eskimo type. From the south boundary of Maine and northwards, and in the regions round the Great Lakes, simple celts, of which many have apparently been blades for adzes, are more common than grooved axes.[105] Of the northern celt-adzes some are large and have apparently been lashed directly on to the shaft, as for instance is the case with those which are ascribed to the supposed pre-Algonkian "Red-Paint People" in Maine;[106] others are much smaller, such as ODIj 9 and ODII 192, both in CNM and from the southeast of Canada and Rhode Island respectively. These celts, however, are different from most Eskimo adze blades in that the cross section of the edge is plane-convex or even slightly hollowed out, whereby the type approaches the wellknown gouges from the North Atlantic area. From a place so far south as Helena, Arkansas, however, there is a small, ground celtadze with lenticular cross section (ODIi 530, CNM). Unfortunately we know nothing of how these implements have been hafted. In the old records from these regions the adze is only mentioned very rarely and no detailed description is given of it.[107]

From Kamchatka[108] and the Kuriles[109] there are stone adzes with edges which clearly differ from the Eskimo type by being ground in a facet on the underside. Munro considers that the so-called fiddle shaped stone implements from Japan are adzes, but supposes that some small celts have been used in the same manner.[110] Some Japanese celts in CNM seem unquestionably to be adzes. From the Stone Age in North China[111] and South Manchuria[112] there are exactly similar celts. With regard to the question of shafting we are just about as badly placed with respect to Asia as to America. In Siberia, Turkestan, etc. adzes of iron are now used, furnished with a shaft hole and a straight shaft. The bent wooden shaft, which presumably is an older type, is known, however, from the Karagass (1339–248, LAM), the Gilyak[113] and North China.[114] At the latter place the blades are of similar type, with a socket, to those already found from the Bronze Age there, the Bronze Age about Minusinsk in Siberia, and the European Bronze Age.

What I have advanced here are merely indications; a really exhaustive investigation would crave a much more detailed study and probably could not be carried to an end satisfactorily with our present defective archæological knowledge of great areas, particularly sub-arctic Canada. Even though it may thus be said that there are points of resemblance between the Eskimo adze and the one that is known from the plateaux in British Columbia (the Fraser-Thompson River area), this material is for the present too little to throw any light upon the origin of the Eskimo adze and its historical place in the culture.

With regard to the needle case, which among the Caribou Eskimos only seems to occur among the Qaernermiut, it is not necessary to undertake such a far-reaching investigation. It is quite different to the characteristic "winged needle case"[115] of the Thule Culture, but has a special, prismatic form which occurs among the Iglulik and Netsilik groups.[116] Thus it is obviously from the north that the Qaernermiut have learned to know the needle case. The dot-and-circle ornament has a very wide diffusion among the Eskimos, but is not found on specimens from the Thule Culture.[117] This conforms to the fact that it appears just on the described needle case from the Qaernermiut and makes it probable that it has come to the Caribou Eskimos in the same manner as the needle case.

Special features of the coast culture: Summary. It will appear from the foregoing that only very few elements have made their way into the culture of the Coast Eskimos from the north, i. e. from the Iglulik group and particularly its most southerly tribe, the Aivilingmiut. In fact these only comprise the elements which are associated with breathing-hole hunting and the needle case. Tower traps, trace buckles, arrows with three radial feathers, and barbed arrow-heads of bone may possibly also be traced to an influence from the north, but it is very uncertain, especially as regards the latter two elements. Furthermore, we may have to reckon with the possibility that they may have come from the Netsilik group, and it is by no means out of the question that they have been taken from the old offshoot of the Thule Culture on the coast of Hudson Bay.

On the other hand it is undoubtedly this offshoot which has allowed the blubber lamp, the lamp trimmer, needle-and-thread tattooing. the bola, eye shade and the closed stone grave to pass down to posterity. It is probable as regards the drying rack and, as already stated, possible with regard to the three feathers, barbed arrow-heads and tower traps.

There remain a number of elements about which nothing can be said with certainty: implements and methods for sea mammal hunting apart from breathing-hole hunting, the vessel with sides of bent, thin wood, the curing of skin by souring the attached blubber, the manufacturing of seal thongs, the ridge tent, the dog harness with parallel loops, the gull hook, glue made of blood, and the adze. In this respect there are, however, two circumstances which deserve consideration: one is that the elements which with certainty can be said to have come from the north, with the exception of the needle-case, form a complete complex associated with a particular method of hunting and almost with a certain event (the wintering of the American whalers); the other is that these elements are only known from the most northerly Caribou Eskimos, the Qaernermiut. To a certain extent this may indicate that the "doubtful" elements. which do not form any organic whole, are a more or less accidental inheritance from their predecessors. One thing is at any rate indisputable: a number of threads still lead from the old to the new.

- ↑ Cf. also Mathiassen 1927; I 107 seq.

- ↑ Ellis 1750; 154.

- ↑ J. B. Tyrrell 1898; 92. Turquetil 1926; 419.

- ↑ I have given a more detailed description of the ruins on Sentry Island in Mathiassen 1927; I 108 seqq.

- ↑ Mathiassen 1927; I passim.

- ↑ Ibidem; I passim.

- ↑ Mathiassen 1927; I 113.

- ↑ Knud Rasmussen 1925–26; I 122, 285; II 16, 120 seqq. Mathiassen 1927; II 186 seqq.

- ↑ Mathiassen 1927; II 15 seqq.

- ↑ Dobbs 1744; 82.

- ↑ Hearne 1795; 391.

- ↑ Dobbs 1744; 8. Ellis 1750; 244, 254 seq. Umfreville 1791; 73.

- ↑ Hearne 1795; xxx.

- ↑ Ibidem, 160 footnote, 391.

- ↑ Ellis 1750; 244, 254 seq. Cf. p. 189 of the descriptive part.

- ↑ Ellis 1750; 256.

- ↑ Dobbs 1744; 49.

- ↑ Mathiassen 1927 I–II, passim.

- ↑ Ibidem, II 58 seq.

- ↑ As Steensby (1917; 154) also assumes. It is known from the Thule Culture, but was not used on Southampton Island, at any rate in recent times. (Mathiassen 1927; II 64).

- ↑ Boas 1888 a: 556, 560. Turner 1894; 178. Hawkes 1916; 39 seq.

- ↑ Mathiassen 1927; I 285 seqq.

- ↑ The methodically interested ethnographer will observe that the "survival criterion" has been utilised without hesitation in this paragraph, although Graebner (1911; 81) opposes this strongly. I cannot see otherwise than that Graebner — justly — points to the existence of a source of error, as elements borrowed from the outside sometimes assume a striking likeness to survivals; but it is a big leap from this to entirely reject Tylor's ingenious theory. Graebner goes so far as to say: "Wo eine Erscheinung unorganisch in ihrem Zusammenhange steht, liegt Übertragung vor" (1911; 96). But hardly anyone will assume that the Caribou Eskimos at the coast have "borrowed" the deerskin kayak or the use of heather fires from the interior.

- ↑ de Charlevoix 1744; I 397. Bacqueville de La Potherie 1753; I 176.

- ↑ Mackenzie 1801; 3 footnote, 20, 123.

- ↑ Handb. Amer. Ind.; I 276.

- ↑ For this reason the objects which Foxe found at Hubbart Point must be from the Cree and not from the Chipewyan. Cf. part I, p. 38.

- ↑ Coats 1852; 33.

- ↑ Coats 1852; 31 seq.

- ↑ Mackenzie 1801; lxxxi.

- ↑ Hearne 1795; 326.

- ↑ Coats 1852; 120, 126.

- ↑ Dobbs 1744; 80.

- ↑ Hearne 1795; 298, 338 footnote.

- ↑ Ibidem, 298, 338 footnote.

- ↑ Mathiassen 1927; II 24, 55 seq.

- ↑ Ibidem, II 53.

- ↑ The other methods of curing sealskin are not shown as separate elements as they are identical with the methods employed for caribou skin. On the other hand the seal thong is included, as the method of manufacture differs from the manner of making babiche.

- ↑ Mathiassen 1927; II 20 seqq.

- ↑ Ibidem; II 36.

- ↑ Glahn 1784; 294 note 1.

- ↑ Kroeber 1900; 283.

- ↑ Hawkes 1916; 73. Pb 1c, CNM, from Hopedale. Boas 1888 a; 493, 500.

- ↑ Mathiassen 1928 c; 52.

- ↑ Mathiassen 1927; I 277.

- ↑ Mathiassen 1927; 11 100.

- ↑ Mathiassen 1927; II 107.

- ↑ Ibidem, I 281.

- ↑ Mathiassen 1928 c; 113.

- ↑ Sarfert 1909; 143 seqq.

- ↑ Mathiassen 1927; II 128 seq.

- ↑ Mathiassen 1927; I 259 seq., II 128.

- ↑ Murdoch 1892; 84. Nelson 1899; 263.

- ↑ Hearne 1795; 322 seq. Skinner 1911; 12 seq. Exactly the same form is also to be found among other northern tribes such as the Naskapi and Ojibway (Turner 1894; 298 seq. Skinner 1911; 119 seq.).

- ↑ Hatt 1916 a; 289. Ejusdem 1916 b; 249.

- ↑ Krause 1921; 33.

- ↑ Goddard 1916; 212.

- ↑ Ellis 1750; 219. Drage 1748; I 186.

- ↑ Howley 1915; 85.

- ↑ Niblack 1890; 304. Boas 1905–09; 417.

- ↑ Lowie 1922; 225 (Crow).

- ↑ Kroeber 1925; 408 seq. (Maidu).

- ↑ Mindeleff 1898; 496 (Navaho).

- ↑ Sarfert 1909; 162. Petitot 1889; 17. Morice 1895; 189 seq. Ejusdem 1906–10; IV 584 note (cit. Schwatką), 586 seq., 589. Dawson 1892; 8. Teit 1900–08 a; 215. Ejusdem 1900; 195 seqq.

- ↑ Sarfert 1909; 162 seq. Krause 1921: 9, 13 seq.

- ↑ Seroshevski 1896; 357.

- ↑ v. Schrenck 1881–95; 375 seqq.

- ↑ Sirelius 1906–11; VIII 8 seqq.

- ↑ v. Schrenck 1881–95; 367, 370 (Orok and Oroche).

- ↑ Huc 1850; II 156. Prschewalski 1884; 144, 197. Rockhill 1895; 701 seq.

- ↑ Torii 1919; 243 fig. 87.

- ↑ Munro 1911; 75 seqq.

- ↑ Mathiassen 1928 c; 78 seq. Cf. Parry 1824; 516 seq.

- ↑ König 1925; 261.

- ↑ Mathiassen 1927; II 130 seq.

- ↑ Boas 1907; 71, 426 seq.

- ↑ Mathiassen 1927; II 62 seq.

- ↑ Ibidem, II 52 seq.

- ↑ Cf. Lyon 1824; 46. Here Lyon mentions from Duke of York Bay "stone huts" which are possibly tower traps.

- ↑ Osborn 1852; 142 seq.

- ↑ Hawkes 1916; 82.

- ↑ Kumlien 1879; 41 Boas 1888 a; 510 seq.

- ↑ Bogoras 1904; 141.

- ↑ It must be added here that the "tower" mentioned from the north shore of Baker Lake possibly, despite its situation in the interior, was not built by the Qaernermiut but belongs directly to the Thule Culture. The latter existed at a time when the sea was 5–15 m higher than now (Mathiassen 1927; I 130) and, as Baker Lake only lies 10 m above sea-level, it must then have been a part of Chesterfield Inlet, which again means that its shores may have been populated by a coast people.

- ↑ Mathiassen 1927; II 55.

- ↑ Hawkes 1916; 86 (presumably the specialised type).

- ↑ P 29: 290, CNM.

- ↑ Bogoras 1904; 150.

- ↑ Mathiassen 1927; II 54.

- ↑ Ib 158, CNM. Jochelson 1925; pl. 17.

- ↑ K 191, CNM. Bogoras 1904; 143. Nordenskiöld 1880–81: II 113.

- ↑ Jochelson 1908; 561.

- ↑ It must, however, be observed that this form of ornamentation has a diffusion which also marks it as belonging to the Thule Culture, presumably originally coming from Asia.

- ↑ Communicated to me by the West Greenlander Jacob Olsen.

- ↑ Boas 1888 a; 526.

- ↑ Lyon 1824; 320.

- ↑ Amundsen 1907; 220.

- ↑ Stefánsson 1914 a; 90.

- ↑ Ibidem, 350.

- ↑ Ibidem, 387 seq. 201.

- ↑ Jochelson 1925; 56, 80.

- ↑ Thomsen 1928; 300. Mathiassen 1927; II 75 seq. Hawkes 1916; 98.

- ↑ Jochelson 1925; 120.

- ↑ H. I. Smith 1899; 142. Ejusdem 1903; 164 seq. Ejusdem 1900–08; 313, 434.

- ↑ Wissler 192; 263 seq., 271.

- ↑ Moorehead 1913; 42.

- ↑ Cf. Beschr. v. Virg. 1651; 30. Doc. Col. Hist.; I 281.

- ↑ Bergman 1923; 413 fig.

- ↑ Torii 1919–21; 274, Pl. xxvii.

- ↑ Munro 1911; 117 seq.

- ↑ G. Anderson 1923 a; 7.

- ↑ Torii 1915; 16 seq.

- ↑ v. Schrenck 1881–95; 509.

- ↑ G. Anderson 1923 a; 7.

- ↑ Mathiassen 1927: II 92 seqq.

- ↑ Spec. in Thule Coll. CNM. Cf. Boas 1907; 94 fig. 136. Hall 1879; 399.

- ↑ Mathiassen 1927; II 124 seq.