The Caribou Eskimos/Part 1/Chapter 4

Motives and geographical conditions. It is possible that in man — and most pronouncedly in primitive man — there is an impulse to wander which forbids him to remain in the same place always.[1] The Eskimos are very fond of travelling and are not usually shy of long journeys, for they make their way hunting, holding the old proverb ubi bene, ibi patria in high regard. A Pâdlimio, who now lives at Hikoligjuaq, read a challenge in the teasing of some Utkuhigjalingmiut, who asserted that his tribe were no travellers. He related that he therefore journeyed to Back River with his family and remained among the Utkuhigjalingmiut for a long time. I dare not guarantee the truth of the story, but it is not improbable.

The psychological motives of the journeys of the Eskimos are, however, powerfully supported by obvious, material inducements, which again are a consequence of the geography of their area. It has been pointed out in one of the foregoing chapters (p. 69 seqq.) that hunting involves a constant moving about; the demands of the hunt are, in reality, the principal reason why a family seldom remains more than one or two months at a time in the same place. But whereas the hunting expeditions keep within narrow limits, that is to say those which underlie the diffusion of the various tribes, other journeys take the Eskimos much further afield. Considerable distances are often travelled for the purpose of fetching a product that is not to be had in the home area, for instance wood or soapstone. Journeys to visit distant relations are also common, and, in addition, a by no means insignificant trade brings together even tribes which live a long way from each other. Journeys to the various trading posts have now to some degree taken the place of the original trading journeys.

The geography of the country has not only influenced the motives but also the methods of travelling, and in this the inland life of the Caribou Eskimos, in contrast to the littoral life of their kinsmen, is very marked. In winter, when other tribes move about with the sledge on the sea ice, the Caribou Eskimo has to keep to the snow of the interior and, even if this is quite firm and hard, it is always heavier to drive on land than on sea ice. In summer they undertake rather long journeys over land, on which men and dogs themselves carry what is required to be taken along. On the other hand, communication by water only takes place to a small extent, because the Caribou Eskimos lack the means of transport for this. Originally the kayak was their only vessel and, if a party of Eskimos have to cross a river or a lake, they are still compelled to tie a couple of kayaks together to act as a ferry (fig. 48). At the coast some of them now have whale boats; but on the average they are poor seamen because only very few of them, like the Aivilingmiut, have been schooled by the whalers. In the interior some have commenced to acquire canoes of Canadian make, but at present their manoeuvring is a sorry sight compared with the phenomenal efficiency of the sub-arctic Indians.

Of means of transport besides the dog sledge and the kayak, the Caribou Eskimos also know tump-lines and pack bags for the dogs. To a certain extent, of course, footwear may also be included.[2] Snow-shoes are an acquisition from the Indians and are only used by a few in the short period between winter and spring. We may thus sum up the means of conveyance in the following table:

| Kind | Winter | Summer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Land | Water | ||

| Personal | Snow-shoes | — | Kayak |

| Baggage | Dog sledge | Tump-lines Pack bags |

— |

This shows that the means of conveyance proper are first and foremost in the service of goods transportation. The kayak is mostly a hunting accessory, and snow-shoes cannot be said to have obtained naturalisation in the culture. The slight development of the means of personal conveyance is apparently a primitive feature.

The possibilities of journeys are present everywhere on the Barren Grounds and in all directions. Nowhere does the topography raise obstacles. The relief of the country is so low and open that at most it may cause a bend in the route, but no stoppage; and, when for three-fourths of the year the country is covered with snow, it is in reality open to communication. In summer the hills are not so bad as the open rivers, which stop the land traveller and, owing to their rapids, are not very suitable for navigation. The vegetation may be left entirely out of consideration in winter; in summer some inconvenience may be attached to forcing the willow thickets in the south; but on the other hand they never grow in such extensive formations as to present any real obstacle. As to the climate, there is only one season of the year in which travelling is difficult — spring, when the snow is soft and, in parts, almost impassable.

The greatest obstacle on the whole is, however, the question of provisions, both for man and for dog. It is exclusively the lack of food which means an element of danger when travelling in these regions; for with the Eskimos' means of communication as they are, the quantity of provisions that can be taken is limited. They are

Fig. 48.Pâdlimiut using two kayaks bound together as a ferry across Kazan River.

therefore compelled to hunt their way forward. But this again reacts upon that which — in contrast to the outer obstacles — may be called the "inner resistance" to communications.[3] As the Eskimos must everywhere procure their food while on the journey, this in the first place becomes protracted as to time, and in the second place requires that hunting implements and articles of personal comfort must be taken along in a volume which, under other circumstances, would be unnecessary. The whole family goes on the journey, as on long trips a woman is almost indispensable for sewing and similar work.

Fig. 48.Pâdlimiut using two kayaks bound together as a ferry across Kazan River.

therefore compelled to hunt their way forward. But this again reacts upon that which — in contrast to the outer obstacles — may be called the "inner resistance" to communications.[3] As the Eskimos must everywhere procure their food while on the journey, this in the first place becomes protracted as to time, and in the second place requires that hunting implements and articles of personal comfort must be taken along in a volume which, under other circumstances, would be unnecessary. The whole family goes on the journey, as on long trips a woman is almost indispensable for sewing and similar work.

On the other hand, social and economic conditions make it difficult for a man to leave wife and children for long at a time. A woman cannot support herself in this country, where the procuring of food is such a strenuous task and therefore, if circumstances positively prevent a man from taking his wife with him, she takes up her abode temporarily in another household. Under these circumstances the familiy is entirely dissolved, and it may be a question whether the bands are later tied again. To diminish the risk he will therefore leave her temporarily to his brother, and he will often try to borrow another wife from a friend. The result is that whether a journey is principally a hunting or a trading trip, there is very little difference in its character. The whole family is set in motion and it is necessary to carry an imposing amount of baggage comprising all kinds of articles. The "inner resistance" of travelling is therefore great. What is more, it is in reality greater than necessary, for much of what the Eskimos consider to be indispensable on a journey would be regarded, for instance by a European expedition, as quite superfluous. It must be remembered, however, that, to the Eskimos, travelling is not a shorter or longer period during which, without feeling the loss, they jettison a few comforts, but it comprises their very daily life. They are not sustained by the prospect of better conditions after a certain time has elapsed, but spend their whole lives travelling.

The inherited manner of travelling has taken root in the minds of the Eskimos to such a degree that it has not been changed by the H. B. C.'s annual mail journeys, which are performed by employed natives. These journeys could certainly be performed much more quickly than is the case now, if the money which is now spent on daily wages were used to provide a sensible outfit.

Geographical and astronomical knowledge. The Eskimos' knowledge of their land and the sky which vaults above it is, of course, both a necessity for communications and a consequence of them, and it would be futile to try to keep these two things separate. Science and mythology cannot, however, be separated at a primitive stage and, if we are to consider the geographical and astronomical knowledge of the Caribou Eskimos, it would be logically correct to do so in combination with an examination of their myths and their religious view of life. Where definite knowledge has its boundaries. there the myths begin, and both run imperceptibly into each other without the Eskimos themselves being aware of the difference. Much of what they regard as natural would be regarded by us as supernatural. It applies to all the fabulous figures with which their imagination populates the country, without these in themselves being regarded as essentially different to human beings, no more than the East Indian monsters which populate the cosmographies of the Middle Ages were looked upon as really supernatural beings.

To differentiate between the natural and the supernatural in the Eskimo view of life is, therefore, to bring into it an element which only has its place in a much higher developed train of thought. Nevertheless, for practical reasons we must make a separation, leaving alone all the mythological matter, but all the same not confining ourselves exclusively to unadorned reality.

The Caribou Eskimos are very familiar with their country. As a rule they know every hill and every lake, and know how to pass on their knowledge by means of excellent maps. It is true that as a rule bearings and distances on these are incorrect, but the wealth of detail is so great that they are capital to travel by and can be used as a splendid supplement to a mapping with astronomically defined points.[4] In itself, however, the sense of locality of the Eskimos is of course nothing unique, and a white man or a man of any other colour would undoubtedly be able to come up to the same level with practice; but there is no doubt that the Eskimos, who from childhood move about here and there, gradually acquire an astonishing knowledge of the country in all conditions and, what is more, an outstanding ability to orientate themselves by means of a number of quick and scarcely conscious decisions as to the position of the celestial bodies, the meteorological state, and so on. And yet there are some of them who entirely lack sense of locality. I heard of a man, I believe a Qaernermio, who was never allowed to hunt alone because he was unable to find his way home by himself, and once in a fog I was led astray by a Harvaqtôrmio only a day's journey from his own camp.[5]

Cairns of stone are often erected to indicate routes or caches, so that they may be seen a long way off; but as they resemble each other at least just as much as do the hills, they are not always particularly informative.

Only exceptionally do the Caribou Eskimos go far outside their own area;[6] but through contact with the neighbouring tribes they have acquired some idea of the adjoining areas, so that at any rate they are all familiar with conditions up to Repulse Bay and the Arctic Sea. Franklin wrote of his Pâdlimio interpreter's knowledge of the more northern Eskimos: "He says, however, that Esquimaux of three different tribes have traded with his countrymen, and that they described themselves as coming across land from a northern sea. One tribe, who named themselves Ahwhacknanhelett, he supposes may come from Repulse Bay; another, designated Ootkooseek-kalingmæoot, or Stone Kettle Esquimaux, reside more to the westward; and the third, the Kang-orr-mæoot, or White Goose Esquimaux, describe themselves as coming from a great distance, and mentioned that a party of Indians had killed several of their tribe on the summer preceding their visit . . . . If this massacre should be the one mentioned by the Copper Indians, the Kang-orr-mæoot must reside near the mouth of Anatessy, or River of Strangers".[7] Richardson has distorted "Ahwhacknanhelett" to "A-hak-nan-helet";[8] this word, however, is no tribal name but means "the northern dwellers" [awaɳnᴀrʟi·t].

Nowadays the Caribou Eskimos have a knowledge of the same groups which Franklin named, viz. the Aivilingmiut [aiviliɳmiut]. who must be identical with "the northern dwellers"; the Netsilingmiut [näc·iliɳmiut] which, among the Caribou Eskimos, means not only the Netsilik tribe in the narrow sense, but the whole of the group which lives from Simpson Peninsula in the east to Back River in the west and, for instance, also includes the Arviligjuarmiut, the Utkuhigjalingmiut, and the Háningajormiut and finally the Kidlinermiut [kidlinᴇrmiut], which is used about all Copper Eskimos, that is to say also about the Umingmaktôrmiut, the Eqaluktôrmiut, etc.

In the south the Caribou Eskimos have some knowledge of the forests, which they have acquired by having seen them during their trading visits to Churchill, and, formerly, Reindeer Lake. They also know some of the more prominent forest animals such as the moose, lynx, black bear, and beaver. The two Indian tribes with which they come in contact are the Cree and the Chipewyan, who are called [unali·t], sing. [unalᴇq] and [itqili·t], sing. [itqilᴇq] respectively. The first word possibly means "the remote dwellers", whereas the last means "they who are infested with louse-nits" and is a derisive name which the Eskimos commonly bestow upon the Athapaskan tribes and which is still remembered in Greenland and used there about the imaginary dog-men of the interior. The Caribou Eskimos generally assert that the [itqili·t] women are only clad — or were formerly clad — in a fringed skirt of caribou skin. No common name such as our "Indians" is known. White men are called [qablunait], sing. [qablunᴀ·q].

At the coast, where there are here and there ruins of earth-covered winter houses, but not in the interior, the Caribou Eskimos will speak of [tun·it], a people who were taller and stronger than the Eskimos of today, but not essentially different from them.[9] It was they who built the houses. They had both kayaks and umiaks and caught seals, walruses and whales, and they were so strong that one man could lift a walrus up on the ice and drag it home. There is undoubtedly a historical foundation for the legend of the [tun·it], who were apparently the carriers of the culture which our expedition has called "Thule".[10] There are, however, many beings which have only been created out of the imagination but which are regarded as being just as real as all others. The Coast Qaernermiut knew the following:

[ᴀrna·nait], a people among whom the women go in kayaks and umiaks and hunt whales. They carry their husbands on their shoulders. Human beings may meet them sometimes when they are hunting.

[iɳnᴇrjugait] live among the rocks and look just like men dressed in sealskins. They are not dangerous, on the contrary they help people, for instance by giving them their hunting spoils. If the carcass of a seal is found, it is a gift from them, and in time of famine the shaman can get meat from them.

[tᴀrqajägʒuit] are a people of shadows. They are so quick that they catch caribou by running them down. They are not dangerous to man.

[ijᴇrqät] are invisible, but they can be heard whistling; only a shaman can see them. If an ordinary person hears them, he must run away.[11]

[kukiligaic·ait] have big claws with which they tear to pieces every man they meet. They live in snow houses.

[inoʷagugligᴀ·rc·ut] are dwarves, clothed in caribou skin. They live in the interior and kill their prey simply by pointing at it. They pursue the foxes, which to them are as bears. When they meet a man they grow in size, knock him down and keep him pressed to the ground, until he dies of hunger.

Several of the West Greenland fabulous beings were expressly stated to be unknown, viz. [qajᴀriʃ·ät], [umiᴀriʃ·ät], [igaliʟ·it], and stone giants. Of fabulous animals the Coast Qaernermiut knew [qiligvᴀq], a big, four-legged animal said to live in the interior.

The Coast Pâdlimiut talk about a people who are called “the people of the skerries" [ik·alrut-inue] or "they who knock" [qadlutᴀ·rpalac·e]. When they are heard knocking at the edge of the beach one must sing: [taima-ila· tainaɳa ikalrun·it qadlutᴀ·rpalac·e], “listen to the knocking down there at the skerries".

The astronomical knowledge of the Caribou Eskimos is not great in consideration of the opportunity which the open prospect and the long, starlight, arctic nights give for observation. Probably the explanation is that the stars, apart from serving as a guide and a certain approximate division of the night, have no signifiance to the Eskimos. Not alone have only very few constellations a name, but in many cases it is impossible to get the statements of one's informants to agree, because very often the names are quite confused. That the Eskimo constellations are not the same as ours goes without saying.

The best known of them all is [tuk'tɔrʒuk] "the Caribou” which comprises Ursa Major, the nearest star in Draco and the clearest in the Hounds. The "Caribou” is pursued by the "Wolf” [ama'rɔrʒɔq], which probably consists of Bootes, Gemma and some stars in the Serpent. The polar star is called [qite'rᴀrʒɔq] "the middle one", and [a·gʒu·k] are two stars which in winter, doubtless about new year's time, appear in the eastern sky. Two stars which I could not get identified either, are called [i'hiƀjuktɔq] and are to be found near the polar star, perhaps in the Little Bear. The Twins, together with Capella and Auriga, are called [qu'tɔrʒuk], "the collar bones". Orion's Belt is called [hiäktut] "the row", and the Pleiads [a·gʒäkta·t] "branches on antlers". Four stars are called [uᵛ’dläktut] "the assembling ones". Finally, I once heard Arcturus called [ublori'ᴀrʒuᴀq] "the big star”, but possibly this is no proper name.[12] The Milky Way has no name and hardly seems to have been noticed. Stars are said to be equal to a sealskin in size.

We will not go into the mythological view of the heavenly bodies. which for instance makes sun and moon sister and brother, nor dwell upon the explanation of certain meteorological phenomena such as thunder, which is due to another brother and sister rubbing a skin: mock suns, which are called "the sun's drum"; lunar halos, which are the white skin tucks on the trousers of the man in the moon, and so on. On the other hand, in connection with the foregoing we will refer to the time reckoning of the Caribou Eskimos. The year is reckoned by winters, sing. {{IPA|[ukiɔq), and there are four seasons: [ukiɔq] winter, [upiɳrᴀ·q] spring, [aujᴀq] summer and [ukiᴀq] autumn. By the affix [-xᴀq] is as usual expressed that which will be something; for instance [upiɳrᴀqxᴀq], that which will be spring, the early spring, and so on. The year is divided into "moons", from new to new. Normally, of course, there should be thirteen, but there are some which lack names and in other cases one "moon" seems to be divided into two. This is quite natural when we look at their names; for with one exception they have no connection at all with astronomy, but only describe the general condition of nature. And by the way there is hardly one Caribou Eskimo who off-hand can name all the months, and it takes quite a cross-examination of several people to obtain a fairly clear idea of them. It is obvious that they cannot be made to agree with our months. Beginning with spring, the Coast Pâdlimiut reckon in this manner:

- [näc·iät] fjord seal youngs (about March).

- [terigluʷit] bearded seal youngs.

- [atᴇrvik] when (the caribou) descent (from the interior) takes place.

- [tuʷa·jᴀrvik] when the firm ice breaks.

Then come three "moons" without names.

- [hikovik] when the ice covers the water (about September-October).

- [nuliᴀrvik] when (the caribou) mate.

- [katagaᴱrigvik] when (the caribou) cast (their antlers).

- [a·gʒulᴇrvik] when the constellation [a·gʒu·k] begins to appear.

- [ta·tqin·ᴀrʒuᴀq] the great "only-a-moon”.

- [awun·ivik] when (the caribou) miscarry (owing to the cold).

Among the Qaernermiut the "moons" are rather different.

- After [terigluʷit] they reckon:

- [iʃäƀrᴀq] walrus young.

- [nɔʀ·ait] caribou calves.

- [man·it] the eggs.

- [ʃag·erivik] when (the caribou) are thin-haired.

Corresponding to [hikovik] and [nuliᴀrvik] they have [akudlerɔrvik], when (the caribou) have medium-long (hair), and [amᴇra·jᴀqvik], when (the caribou) rub their antlers. The moon near the shortest day is called [adlinᴀqtɔq], when one is under taboo (probably against eating and drinking in the open air); this is due to the solstice. Finally, they put [awun·ivik] before [tatqin·ᴀrʒuᴀq].

Knud Rasmussen has given me the following list of the periods as far as concerns the Inland Pâdlimiut. It is still more impossible with these to make them agree with real months.

- [tukiliᴀrvik] when (the caribou) turn towards the settlements (about April).

- [imiɳnᴀ·rqivik] when (snow-house roofs) fall in.

- [atᴇrvik] when (the caribou) descent takes place (about May).

- [aviktᴀq] the divided (i. e. there is open water in the rivers, but ice on the lakes).

- [kanraläk] caribou in moulting time

- [aic·a·n] when (the young birds; yawn about July).

- [tuktunigvik] when the caribou come (back). about

- [akudlᴇrɔrvik] when (the caribou) have medium-long hair) ( August

- [amᴇra·jᴀqvik] when (the caribou) rub their antlers

- [niglihᴀrvik] when the small waters freeze.

- [hikohᴀrvik] when the big lakes freeze.

- [nuliᴀrvik] when (the caribou) mate.

- about September.

- about October―November

- [katagaᴱrigvik] when (the caribou) cast (their antlers)

- [idlivik] when (caribou) foetuses form.

- [awun·ivik] when (the caribou) miscarry.

- [tatqin·ᴀq] only a moon.

The Inland Pâdlimiut also know a "moon" by name [a·gʒulᴇrvik], whereas its place among the others is not certain; presumably it should be inserted after [katagaᴱrigvik].

Journeys and trade: Original state. As has already been stated, the motives make it possible to differentiate between hunting, "fetching", visiting and trading journeys. The first have already been mentioned in connection with means of subsistence and may therefore be passed over here. By "fetching journeys" I understand those which concern the products which are not to be found on the spot, but must be fetched from other regions. These are commodities such as wood, which is taken from the small copses in the southern river valleys and also in the form of drift wood in lower Thelon River, or soapstone, which occurs at Qiqertarjuaq, Rankin Inlet and Thaolintoa Lake. These products do not demand any particular skill to procure them, as for instance is the case with sea mammal products, and therefore the Eskimos prefer, within reasonable distances, to fetch them themselves instead of trading for them.[13]

Visiting and trading journeys are to some extent very closely connected, but whatever may be the primary motives — whether a meeting between families from various places is accidental or intentional — it is obvious that it always leads to a certain amount of trading. A considerable part of this consists in the exchanging of gifts. Even if in this respect too there have been changes under the influence of civilisation, there are distinct traces of the fact that a gift always craves a gift in return. This is a feature that has often been observed among untouched Eskimos; only it must be remembered that the distribution of meat which takes place after the hunt is not, in the minds of the Eskimos, a distribution of gifts but a right, which does not crave any direct return. The distribution of gifts is a permanent institution on visiting journeys, in the event that the guest and one of the hosts are [iglori·k] "song-cousins". In that case there are song-feasts the first two evenings, during which the gifts are exchanged.

One day at Eskimo Point a man, Tuktuitsoq, who was a "song-cousin" to one of the inhabitants of the place, Haumik, arrived from the south. At the feast of welcome, which was held in the evening in one of the big deerskin tents, the dance was opened by one of the settlement's own inhabitants, that is to say, as the drum was not yet tuned he merely stood still on the floor. Then Tuktuitsoq came forward. He did not actually beat the drum, but just touched the skin lightly with the stick and, during the dance, he was given a rifle as a present, and this he then held in his hand together with the drum. After this it was Haumik's turn, and then Tuktuitsoq danced as before, but this time was given a big woollen blanket. Haumik, who had remained out on the floor, rubbed noses with him during the dance. The next evening there was dancing again, on which occasion Tuktuitsoq handed over his return gifts. On another occasion a man arrived who was "song-cousin" to Huluk, a female shaman at Eskimo Point; he, too, received a present of a gun, so that these gifts, as will be seen, do not consist of trifles. When the gifts are presented the two persons concerned usually shout several times in turn [tamalrutiga] "my all and everything", to which the other answers [höi].

There is no doubt that in former days there was also actual trading besides the exchanging of gifts; but only a hair's breadth separates the two forms of exchange from one another. It is only after the coming of the whites that a certain fixed measurement of values begins to be perceptible. Originally, an object had just so high a value as corresponded to the demand of the moment. As long as this lasted, no capital could be accumulated, and so long has the whole exchange been more a social than an economic phenomenon.

Trading proper has of course mostly concerned such things as could not, or at any rate only with difficulty, be procured on the spot. As each family as a rule makes such indigenous products as it has use for itself, it is obvious that trade within the Caribou Eskimos' own group is very unimportant, and the split between a coast and an inland group makes no essential change in this. The inland tribes may now and then buy a length of seal thong or a walrus tusk from the coast; but this trade never amounts to much, as they just as often use babiche and antler. The coming of the whites has not visibly changed the intratribal trade. The coast population themselves had the best opportunity of disposing of their furs, and, on the other hand, Churchill is not further away than that the inland Eskimos also preferred to travel to the stores of the Hudson's Bay Company themselves in preference to using the coast dwellers as intermediaries.

With the neighbouring tribes the Caribou Eskimos have from olden times carried on a trade which perhaps is not particularly important in extent, but still big enough to keep them in constant contact with their kinsmen. As the basis of this intercourse the Caribou Eskimo's possess the incalculable advantage of having easy access to wood, and, when the Hudson's Bay Company established its trading post at Churchill more than 200 years ago, the possibility was also created of a primitive transit trade across the Barren Grounds to the Eskimos living more to the north. On the other hand the latter had, as a means of barter, seal thong, sealskins for boots and, as regards Bathurst Inlet, copper too. When European goods appeared in the market, their furs, especially fox furs, attained a value undreamed of.

As already stated, however, the various products of the sea are not in particular demand among the Caribou Eskimos. It is possible that copper was more important in earlier times, if this metal does not mean a fairly new culture conquest for the Eskimos at Bathurst Inlet too, as Jenness thinks.[14] Ever since the establishment of Churchill and up to the opening of a number of new posts within recent times, furs were apparently by far the most important; for the prices which the Caribou Eskimos demand for European goods when they trade with remote tribes give them a profit of several hundreds per cent.

The Caribou Eskimos were able to trade sea products and furs from the Aivilingmiut, from various tribes of the Netsilik group and from the Copper Eskimos, as Franklin's report already shows.[15] The Aivilingmiut's intercourse with the whalers has long since broken off the connection which formerly existed between them and the Caribou Eskimos. There is, however, evidence of its existence in the fact that Parry found among the Aivilingmiut and Iglulingmiut both men's and women's knives which had come from the H. B. C., two copper kettles, an iron axe, etc.; even in the graves at Repulse Bay there were weapon points of iron. He also mentions that they fetched meat trays from Nuvuk, south of Wager Inlet, and as there is as little drift wood there as on other parts of the coast, this must mean that the trays were traded from the south.[16]

At present the most important trading goes on with the Netsilik group; for although members of both the Utkuhigjalingmiut and the Háningajormiut make trading journeys to Baker Lake, the way is so long that a part of the trading still goes on with the Qaernermiut as middlemen. Just now there is a very clever Qaernermio, Ilatnâq, who has secured practically a sort of monopoly in this middleman business and who makes several trips every winter to the watershed between Baker Lake and Back River, where he meets Eskimos from the north. Chief Factor Anderson, on his journey down Back River in 1855, found that the population at MacKinlay River — presumably the Háningajormiut — must indirectly have been in connection with Churchill, "as they possessed a few of our daggers, beads, files and tin kettles . . .".[17]

The Copper Eskimos live still farther from the Caribou Eskimos than the tribes named; nevertheless it is the trading connection of this group that has especially attracted attention — rather undeservedly, it is true. It is that which is connected with the Akilineq which has, by Stefánsson, been made into a sort of centre for the whole of the Eskimo world.[18] Akilineq is the name of the ridge at Thelon River near Tibjalik Lake (see foot-note 1 p. 30). It was particularly a favourite meeting place when caribou and birds were numerous in spring and summer.[19] The fact that this trading connection has at all been set up was, at the beginning, scarcely the result of commercial causes. There could not have been any reason for the Caribou Eskimos to acquire sea products from so far away and in such a difficult manner, and it is doubtful whether copper has ever been largely used among them.[20] Thelon River, however, exercises a natural attraction in another manner, because it is the nearest place from which the northern Caribou Eskimos can fetch wood. In the same manner it attracted the population of Ogden Bay and Bathurst Inlet, whereas the more westerly Copper Eskimos went to the region round the source of Dease River.[21]

That under these circumstances the two groups met and of course traded too, is obvious; but it is very improbable that this trade developed much before the access of the Caribou Eskimos to procure European goods and, at the same time, to sell furs disturbed the old-time equilibrium.[22] According to everything our expedition has been able to learn, Stefánsson's views of the importance of this connection are greatly exaggerated;[23] to a certain extent, however, he may be excused, inasmuch as he seems to have secured his information just when the importance of the place was at its highest. He writes himself: ". . . . a flourishing intertribal trade exists between Hudson's Bay and Kent peninsula, started by the Eskimo who accompanied Hanbury on his journey. Every winter now there arrives at the village of Umingmuktok on Kent peninsula a tribe known to the Coronation Gulf people as Pallirgmiut (i. e. Pâdlimiut), named, as they say, from a branch river 'Pallirk', which flows into the Akkilinik".[24] The goods thus traded were spread so widely among the Copper Eskimos that at Prince Albert Sound he found "many metal articles, one shirt, one red knit woollen hood, etc." acquired in this manner.[25]

I doubt very much that the Pâdlimiut have been such frequent visitors to Kent Peninsula and Bathurst Inlet (it must be remembered that Stefánsson has not been to these places himself and therefore probably has his information at second hand). The connection has undoubtedly taken place at Thelon River. Jenness, however, mentions a "Pâdlimio" who visited Coronation Gulf during the sojourn of the Canadian Expedition there.[26] I received Jenness' work at such an advanced stage of my journey that I was no longer in touch with the Inland Pâdlimiut, but only with the coast group, and of these nobody knew a person of the name given by Jenness. This of course need not mean that the man in question is not a Pâdlimio, although it must be remembered that they mostly know each other, and it is also strange that during our stay in the interior the year before we heard nothing of any Pâdlimio who had visited Coronation Gulf. It seeins most probable to me that the Copper Eskimos use the term Pâdlimiut about all Caribou Eskimos, in the same manner as the latter call all Copper Eskimos Kidlinermiut and the whole of the tribal group between Pelly Bay and Back River Netsilingmiut. It is said that the Eskimo in question later on disappeared in the vicinity of Great Bear Lake, murdered by the Indians according to the belief of his kinsmen.[27] Now that a trading post has been erected at Kent Peninsula, the connection with the Copper Eskimos has lost its importance.

The Caribou Eskimos have always been hostile towards the Indians. In the first half of the eighteenth century they often warred against the Cree, for as the latter ascribed all evil events such as sickness, unsuccessful hunting, etc. to the Eskimos, there was of course enough to be revenged for.[28] The wars entirely consisted of brutal ambushes and attacks against each other. When the Chipewyan later on placed themselves in between the Cree and the Eskimos, the relations between the latter and their new neighbours became no better than they had been with the old ones. In 1756 the Chipewyan attacked an Eskimo camp at Dawson Inlet and killed more than forty people because two prominent Indian tribesmen had died during the winter,[29] and their massacre of the Eskimos at Coppermine River not twenty years later has attained Herostratic fame. But on other occasions the Eskimos have scarcely been much better than the Indians.

Only a generation ago the Chipewyan spoke of the Eskimos as cannibals,[30] and on the other hand the confidence of the Eskimos in the Indians is no greater than this conception would indicate. Franklin says that the fights between them had ceased in his time,[31] and they have scarcely been resumed since. Still, an old Harvaqtôrmio woman at lower Kazan River was convinced that the Chipewyan had carried away her brothers and sisters when they were little.[32] Both at Hikoligjuaq and at Eskimo Point they speak of an event which took place as recently as in 1920. Knud Rasmussen has related the story as it is told in the interior;[33] the version at the coast is briefly as follows:

An Eskimo had been on a trading trip to one of the H. B. C. posts and was on his way back in company with three Indians, who had also made purchases. The Indians expressed a wish to buy one of the Eskimo's dogs, but he refused, because he had a heavy load and at any rate wished to be nearer his home before he would think about selling. The Indians then conspired to kill the Eskimo; one of them, however, betrayed the plan to him and said that when he gave him a sign by touching him with his foot, he was to flee. In the evening they made up a big fire and put up a gallows (?!); but the Eskimo seized his rifle and ran into hiding, from which he shot the two who were after his life. Then he started on his way to his own settlement, leaving everything behind him; the way was long, however, and he had bare feet (had worn the soles off his boots?) so that at last he could not walk. But after a time he was found by his wife.

The discrepancies in the story as told at Hikoligjuaq are so few and unimportant that one is tempted to believe that there is a historical core; but how much truth it contains on the whole cannot be decided. In any case it is characteristic of the relations between the two peoples, and it goes without saying that events of this kind, which perhaps have not taken place but which at any rate are believed, are not the best possible soil for the cultivation of peaceful intercourse. Now and then, however, they have traded together.[34] The Chipewyan are extremely eager to buy Eskimo dogs and — nowadays at any rate — caribou skins, and soapstone for pipe-bowls in former days. In exchange the Eskimos receive pyrites, mittens, snow-shoes and moccasins. Among the population at Eskimo Point, who frequently visit Churchill, several men own snow-shoes and, in summer, many wear Indian moccasins.

It is characteristic of the relations between the Eskimos and the Indians that the former are always the superiors, particularly by virtue of their prosperity, and as soon as a whale boat with an Eskimo crew arrives at Churchill, a crowd of Indians gathers immediately to beg meat and skin. Not a few Chipewyan speak broken Eskimo, but no Eskimo lowers himself to speak Chipewyan. They converse with each other politely and use the term [ᴀrnaqätiga] "my cousin"; but no affection is observable and, as far as possible, the Eskimos keep to themselves while at Churchill.

Journeys and trade: Intercourse with white men. The first white men's products which the Caribou Eskimos learned to know seem, strangely enough, to have come from Denmark. As mentioned before (p. 64) they originally extented their summer trips to the mouth of Churchill River, and thus the wreck of Jens Munk's ship and the houses of the expedition could not escape their attention. In 1631 Luke Foxe found several graves at Cape Fullerton and writes about the grave goods: "Their Darts were many of them headed with Iron (and nailes), the heads beaten broad wayes. In one of their Darts was a head of Copper, artificially made, wch I tooke to be the work of some Christian, and that they have come by it by the way of Canada, from those that Trade with the English and French".[35] One may disregard Foxe's own hypothesis with an easy mind; and most probably these metal articles have found their way to the north just from Churchill; less probable, I think, is the possibility which Christie mentions, that they came from Button's deserted ship at York. This may apply to the Indian objects which Luke Foxe found at Hubbart Point (see p. 38) for both this place and York are within the Cree Indian area, but, having regard to the slight intercourse between the Indians and the Eskimos, scarcely the objects from Cape Fullerton.

The regular trade of the Eskimos with the whites began a few years after the establishment of Fort Prince of Wales at Churchill River. The Hudson's Bay Company had learned to know the Eskimos by sailing through Hudson Strait, where a lively bartering gradually developed at Savage Islands, and soon afterwards trading was commenced with the people on the west coast of Hudson Bay. It is probable that at first not many Eskimos ventured to the fort, where they ran the risk of meeting the Cree; now and then, however, the Company sent a sloop north along the coast. The criticism which was raised against it in the eighteenth century was, however, for the greatest part against the fact that the regular sailings were being neglected and that the Eskimo trade could have been worked up much more.

Dobbs writes: "The Company at preſent ſend a ſloop to this Latitude (62° 30' approx.) annually from Churchill to Whale Cove. where they trade with the Eſkimaux for Whale-fin and Oil...".[36] Robson reports: "A ſloop is indeed ſometimes ſent to Whale-cove for a few days in a ſeaſon and ſometimes not ſent at all. The people, therefore, having no dependance upon our coming to trade with them, take very little care to provide a ſupply larger than is neceſſary for their own ſubſistence".[37] In 1756 and later in 1767, some Eskimos however allowed themselves to be persuaded to return with the sloop to Fort Prince of Wales and spend the winter there,[38] and with this the ice seems to have been broken. Before the end of the eighteenth century the Eskimos had already accustomed themselves to visiting Churchill regularly, where they bought knives, arrow and spear heads and old nails.[39] But until the Chesterfield post was established in 1912, a boat was sent every summer from Churchill to Marble and Rabbit Islands, where the Eskimos used to camp in order to wait for the traders.[40] In an earlier chapter attention has been drawn to the remarkable fact that in the eighteenth century the company bought baleen and oil on these trips[41] and that this probably has something to do with a change of habitation in these areas (see also pt. II p. 11 seq.).

With regard to the radius within which Eskimos came to these trading rendezvous at Marble Island, Lofthouse has rather exaggerated ideas; he considers that they came there "from Bathurst Inlet, Repulse Bay, Cape Fullerton and Baker Lake".[42] Of course, the Aivilingmiut may go far south (for instance I know one who stayed for a long time with his wife at Port Nelson and York when the Hudson Bay railway was building); furthermore, Jenness says that Copper Eskimos have sometimes remained among the Caribou Eskimos for a year or two and have visited Chesterfield Inlet. These, however, are purely exceptions. If Eskimos have ever come from Bathurst Inlet and Repulse Bay to Marble Island other than women who may have married into the tribes of the Caribou Eskimos, it must be said to have been accidentally.

For more than a hundred years Churchill was the place to which the Eskimos came from all corners of the Caribou Eskimo area to trade. Sometimes they travelled by sledge all the way, starting in the autumn and only arriving home in the spring;[43] on other occasions they travelled by sledge to the coast of Hudson Bay and on by kayak or, in later years, by whale boat. Thus near Driftwood Point in the beginning of July Rae met three kayaks on their way to Churchill, and at Cape Fullerton he saw a man from Chesterfield who the year before had been at Churchill.[44] Both J. W. Tyrrell and Hanbury met Eskimos at lower Thelon River who were well known at Churchill.[45] In addition, European goods of course passed from hand to hand, for as a rule it was only a few of the tribe who made this long and difficult journey every year, and then they usually took along with them in commission the furs of those left behind. In an indirect manner the Eskimos whom the Tyrrell brothers met north of Dubawnt Lake had obtained a pair of moleskin trousers, a large tin kettle, two old guns and a telescope.[46]

The wintering of the whalers at Marble Island and Fullerton in the latter half of the nineteenth century had most influence upon the Qaernermiut, who thus obtained direct access to European goods. By the establishment of the H. B. C. post at Reindeer Lake the Eskimos in the southern part of the interior were also put into closer touch with the whites and "about Christmas-time a few Eskimo come in from the far north, bringing (musk-ox) robes and furs to trade for ammunition and tobacco".[47] Within the area of the Caribou Eskimos the Hudson's Bay Company, at the time the Fifth Thule Expedition visited the country, had posts at the mouth of Chesterfield Inlet, Baker Lake, Eskimo Point and Ennadai Lake, and I understand that a post has now been opened at Dawson Inlet. The firm of Lamson & Hubbard had two posts which are now abandoned, at Chesterfield Inlet and Baker Lake; Révillon Frères had a post at Nueltin Lake and are said to have opened another at Baker Lake. Thus practically every one of the past few years has seen new enterprises, some of which have failed, it is true; but it brings about a keen competition between the various trading firms which, in some respects, is to the

Fig. 49.The Hudson's Bay Company's post at Baker Lake: the trading centre of the Barren Grounds.

advantage of the Eskimos, because they thus receive higher prices, but which on the whole is morally ruinous to them, as each post tries by all means (not all of them equally creditable!) to attract them.[48]

Fig. 49.The Hudson's Bay Company's post at Baker Lake: the trading centre of the Barren Grounds.

advantage of the Eskimos, because they thus receive higher prices, but which on the whole is morally ruinous to them, as each post tries by all means (not all of them equally creditable!) to attract them.[48]

As a consequence of the geographical situation of the posts it is mostly the Qaernermiut and the Aivilingmiut who go to Chesterfield. Baker Lake, which is the greatest trading centre (fig. 49), is visited by the Utkuhigjalingmiut, the Háningajormiut, the Qaernermiut, the Harvaqtôrmiut and the northern Inland Pâdlimiut. Those of this group who live more to the south go to Ennadai and Nueltin Lakes, whereas Eskimo Point is visited by the Hauneqtôrmiut and the Coast Pâdlimiut. The journeys which the Eskimos have to make in order to come to a post often take months. An impression of how frequent the journeys are, and what a great area a single post rules over, may be seen from the following records from the H. B. C. post at Baker Lake in 1922, written at the end of the winter when the sledges come in for supplies for the summer.

| March | 24. | Arrived ourselves at Baker Lake from Chesterfield. |

| — | 25. | Qaernermiut, Háningajormiut and Utkuhigjalingmiut sledges. |

| April | 1. | Harvaqtôrmiut and Qaernermiut sledges. |

| — | 6. | Harvaqtôrmiut sledge. |

| — | 10. | Utkuhigjalingmiut sledge. |

| — | 17. | Hauneqtôrmiut sledge. |

| — | 18. | Qaernermiut sledge. |

| — | 19. | Qaernermiut sledge. |

| — | 20. | Harvaqtôrmiut sledge. |

| — | 21. | Qaernermiut sledge. |

| — | 22. | Háningajormiut sledge. |

| — | 28. | Utkuhigjalingmiut sledge. |

| — | 29. | Harvaqtôrmiut and Utkuhigjalingmiut sledges. |

| May | 5. | Harvaqtôrmiut and Hauneqtôrmiut sledges. |

| — | 7. | Mail sledge from Chesterfield. |

| — | 9. | Harvaqtôrmiut sledge. |

| — | 12. | Knud Rasmussen arrived from Chesterfield. |

| — | 15. | Left for Baker Lake. |

The monetary unit of the Hudson's Bay Company is a "beaver" or a "skin", a plain little stick of wood called by the Eskimo [qijuk] "wood". Its value is 50 cents. It is obvious that such an extremely high minimum unit does not exactly help to make the goods cheap. The money never goes outside the shop, but is paid out over the counter for the skins traded and accepted again immediately for the goods sold. In this manner the Eskimos are invited, indirectly of course, to spend all their money at once, and sometimes they stand cudgelling their brains in order to think of something to buy. If a man is known as a good fox trapper he can obtain extensive credit, for the Company know that they risk nothing as regards the Eskimos. Although the fox skins are often handed over rolled up and frozen, it is seldom that the Eskimos use the opportunity to cheat. I only remember one case, where a piece of hare skin was sewn on instead of a head.

Dogs. In travelling on land, dogs play an important part both summer and winter, whereas their employment in hunting is comparatively limited, especially now when the musk-ox is no longer hunted. They are all of the common Eskimo breed with thick coat, pointed snout and pointed ears, and turned-up tail. Both their coat and their feet, which do not suffer from changing conditions, give the Eskimo dog a wonderful advantage in the Arctic over other, bigger and more willing breeds.[49] Colour and build are like those of the Greenland dogs. The coat moults in summer or autumn, when the dogs are in good condition and have nothing to do. It is important that moulting sets in before the cold arrives, as otherwise they would freeze in the old coat in winter, even if given plenty of food.

Taking them all round, the dogs of the Caribou Eskimos are slightly bigger than those of the West Greenlanders, but they are thinner and have not nearly so much spirit. They are never heard howling with impatience to start, when they are inspanned to the sledge, and only a prospect of running down game can disturb their calm. Although I have never succeeded in finding any certain case, it is asserted that wolves sometimes mate with bitches in heat. Their offspring are said to be even leaner than usual, but big and strong and make good sledge dogs. As to disease, distemper is not rare, and sometimes rabies seems to occur.

The Caribou Eskimos have only few dogs, one reason being that it is impossible to keep large numbers of them when their feed consists entirely, or almost entirely, of caribou meat. It does not contain nearly as much nutriment as seal or walrus meat, particularly when it is frozen. Furthermore, in the year before we came, a violent epidemic of distemper had ravaged the country, and for instance at Hikoligjuaq I saw two sledges tied together and harnessed to one dog. Naturally the owners themselves had to push; this is done in this manner: the tent poles are lashed cross-wise over the other load so that a length sticks out at either side, and the men push against this. Stefánsson says: "The largest number of dogs I have ever seen among Eskimos who did not have guns is three to a family".[50] Although all Caribou Eskimos now have rifles, the number of dogs on the average is not greater among them, and, when a bigger team is required for long journeys, it is common for several families to put all their dogs together.

The Caribou Eskimos treat their dogs neither better nor worse than other uncivilised Eskimos. They do not tend them so well as the Greenlanders; but they are rarely so directly cruel to them as I have often been told by whites about the sub-arctic Indians. Castrating of dogs is unknown. Pups are allowed to come into the tent or snow house when it is cold, and the children often play with them. On the other hand it is a very rare occurrence to see anyone pet a grown dog.[51] But they all have a sort of superstitious veneration for dogs. A Caribou Eskimo may be a murderer, but it is with difficulty that he can be moved to kill a dog, even if it is sick, and this is in no way from fear of suffering economic loss, for he is just as reluctant to do it if the dog belongs to another as if it were his own. Nor will anyone flay a dog, and they will barely touch a skin. In the Hudson's Bay Company's store at Baker Lake I have seen a whole crowd of men refuse to touch a skin, because a doubt arose as to whether it was that of a wolf or a dog.

When the dogs are not being used they are allowed to fend for themselves, and therefore they rarely become attached to man. This, however, is the latter's fault, for they very readily become very affectionate towards anyone who takes care of them. They are not fed more than once every other day and, if food is short, or the dogs are not being used, there may be a longer interval between meals. But that they are only fed every tenth or twelfth, and sometimes every twentieth day, as Gilder says,[52] must be a great exaggeration. But on the other hand in summer they have to manage themselves by eating human excrement and catching lemmings and marmots. The usual feed is caribou meat, raw, and in winter frozen; at the coast in summer the meat of sea mammals. Bones are taboo for dogs and therefore they must never gnaw them.[53] Fish, which is almost the only dog feed in Alaska and is also in extensive use in Greenland, is practically never used. The dogs are always hungry, and neither deerskin clothing nor seal thong and babiche are safe from their marauding, for which reason everything is put up on to snow blocks or is hidden. The Caribou Eskimos are not in the habit of knocking off the points of the fangs, as the Polar Eskimos do to prevent the dogs from destroying their possessions.

In winter the dogs are never tied up; but as soon as a halt is made, they are released from the harness. This is an advantage to the dogs when the harness cannot be dried; for by this means it escapes from becoming saturated with sweat and wet through the dogs lying on it, and then freezing stiff. As a rule the dogs sleep in the entrance passage or in lee of the snow hut, where in the morning they are often completely enveloped in snow, and all that can be seen of them is a number of small snow-drifts on the white, flat surface. It is only Jack London's sledge dogs that dig themselves comfortable holes in the snow.

In spring and summer, when snow erections cannot be built, it is more difficult to keep the dogs at a safe distance from what they consider to be eatable, and then they are often tied up near the camp. Among the Harvaqtôrmiut I saw a dog tied to a large, conical wooden block which was driven into the snow. At Eskimo Point the dogs were tied to stones.

Every dog has its own name, and not uncommonly they are called after human beings, alive or dead. A well-to-do Pâdlimio at Eskimo Point had the following dogs:

| [kupik] | called after his father-in-law |

| [ᴀrnᴀq] | called— after— his— mother-in-law |

| [ᴇrqe·] | called— after— his— wife's brother |

| [qᴀritᴀq] | called— after— his— wife (still alive) |

| [o·tᴀ·q] | not called after anybody |

| [nipidgumᴇq] | not— called— after— anybody— |

| [manerᴀq] | not— called— after— anybody— |

In the team one of the dogs is always the master, and he rules despotically by means of a consistent terrorism. The one he bites gets all the rest of the team after him; in this respect these dogs are strikingly like human beings. The master dog attains his position by fighting for it, and must not be confused with the leader, who is appointed by the owner by virtue of his docility and his skill in following a track. The leader has the longest trace and runs at the head. A bitch is often good as a leader, for the rest of the team pulls hard in order to come up with her.

The Caribou Eskimos are very poor dog drivers. The sporting spirit which makes the West Greenlanders find out the individual peculiarities of the dogs and exploit this psychological insight while on the trail is quite foreign to the Caribou Eskimos. Their journeys are a steady plodding to the accompanyment of an incessant shouting and use of the whip. As a rule the dogs are unwilling to pull and must be threatened or enticed all the time, by for instance someone, usually a woman, walking ahead. When she has gone some distance from the sledge, she squats down, pretends to eat and throws her mittens on the ground. The dogs then think they are pieces of meat and are ready to burst the traces in their endeavours to get up to the supposed tit-bit. But if this manoeuvre is repeated often, the disappointments affect the dogs' spirits, and therefore it is a stimulant which must not be used too frequently. The really good driver uses both his whip and his voice as little as possible, the result being that the dogs immediately obey the signal when it is given.

It is almost impossible to reproduce the dog signals of the Caribou Eskimos.[54] When the team is to swing to the left, the driver cries [haɔʀ·] or [ʰɔᴿo], both syllables together being no longer than one ordinary, long syllable. "To the right" sounds like [awa’ä] or [awa’ᴿe], with heavy stress on the last syllable, and, in encouraging the dogs, the same signal is used followed by a long-drawn [wɔ··r]. “Stop” is a long and dismal [ha·u] or [hö·ᵘ].

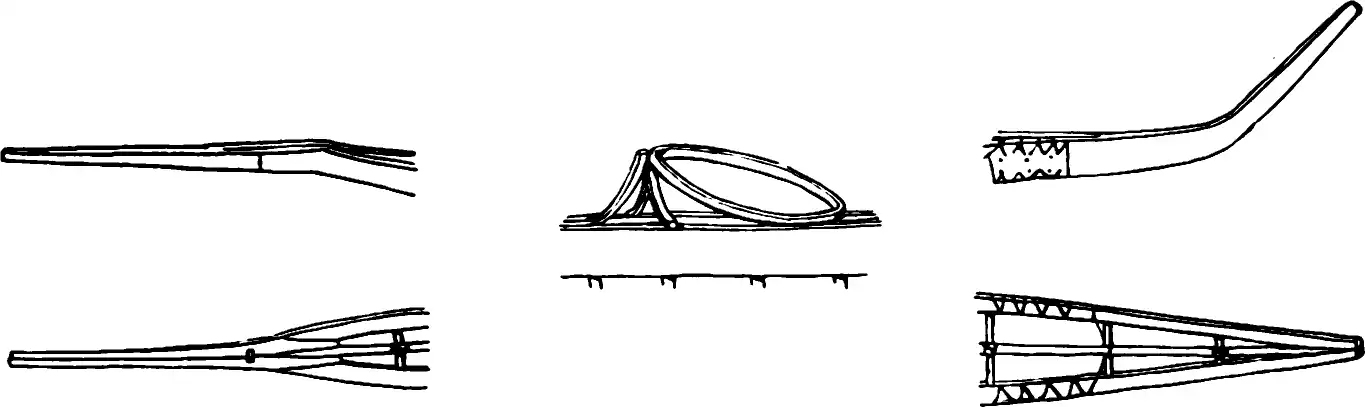

Sledges and their appurtenances. The sledge [qamutik], dualis of [qamut], a runner, can be used during three-fourths of the year and is the most important means of conveyance of the Caribou Eskimos. On the long travelling sledges they take loads which sometimes weigh more than 500 kilos, and they also have small, short ones for hunting trips. Whether the sledge is large or small, the construction is practically the same and, as among all Eastern Eskimos, very simple. It consists merely of runners and cross-slats and always lacks. even the uprights with which the sledges in Greenland always, and in Baffin Land often, are provided. The type which most closely resembles that of the Caribou Eskimos is that which is to be found among the other continental Central Eskimos and in the north of the Labrador Peninsula.

Whereas the northern Caribou Eskimos, especially the Qaernermiut, nowadays usually buy wood for sledges from the trading posts. the southern groups nearly always obtain their wood from the small fir copses which grow north of the timber line. The sledges are always very narrow and very long, the extremes in both directions being reached among the Pâdlimiut, where one may see sledges up to 10 m in length and not even half a metre in breadth. In such cases each runner usually consists of two pieces joined by scarfing, nailed together and sometimes additionally secured by iron bands. The runner is low, very broad and quite roughly hewn, so that in places the bark is left on the outer side. It is thickest about a third of the distance from the head; both ahead and behind this spot the runner is hewn away from the inner side and the under side, so that it gradually decreases in breadth and height. On the other hand, not the slightest attempt is made to bend the nose upwards. Thus whilst the upper edge still forms a horizontal line, the lower edge only touches the Image missingFig. 50.

Dog sledge.

snow along a comparatively short distance, in front of and behind which it rises up from the ground. Holes are drilled along the upper edge for the cross-slats. As among the Polar Eskimos — but in contrast to the rule in West Greenland — two holes are bored in each runner for each cross-slat, which makes it easier to lash it on firmly than if there were only one hole, and, as the runner is already so thick, it is of no consequence that the increased number of holes of course decreases its solidity.

The cross-slats, sing. [napo], may, especially among the more northern groups, be of antler; but in most cases they are of wood. They are always only very slightly worked; the rearmost are rarely more than plain sticks of about the same thickness as breadth and with all the incidental curves of the tree retained. The foremost, on which the greatest weight rests, are as a rule widest at the middle and thinner out to the ends. On the big travelling sledges two holes are bored in each end of the cross-slats, these holes running horizontally in the longitudinal direction of the sledge. Through these holes and the corresponding holes through the runners the cross-slats are lashed on. As a rule this lashing is quite simple, the thong, whether seal thong or babiche, only being passed through each hole once. Often it is the same long thong that is passed from cross-slat to cross-slat. On long sledges there are more than twenty cross-slats; but, with the astonishing lack of accuracy among these Eskimos, it is nothing unusual for one or more to be missing. A fourth or more of the forepart of the sledge is left without cross-slats, so that these only begin a little in front of the place where the runners are thickest.

At the front a thin stick may be let in between the runners to hold them in position, if the sledge is newly made, and in any case there is a line. stretched across between the runners, on which the traces rest in order to prevent them from getting under the runners. Furthermore, just in front of the foremost cross-slat a long draught line [pituk] is fastened, and on this the traces are made fast. It is fastened with two loops in corresponding holes on the upper edge of the runner, and reaches about half a metre in front of the nose. It is joined on one side with a loop and a heavy toggle, which is often of musk-ox horn. The Iglulik group and the Eskimos on southern Baffin Land sometimes use a pierced buckle of special form instead of this simple toggle,[55] but this is not known to the Caribou Eskimos. On the other hand, in the Thule collection from the Hauneqtôrmiut there is another type of buckle (P 28: 116; fig. 54 b) which is almost identical with one used by the Netsilik group. This specimen is of ivory, narrow and pointed at one end. The upper side is slightly rounded, the lower side concave with a prominent keel, which stretches from the pointed end to a little way from the opposite end. The keel is broadest at the top and pierced longitudinally by a channel from its rear end to the middle of its upper surface. Length 8.6 cm, breadth 3 cm. The buckle is fastened to one end of the draught line, the loose end of the thong being passed through the channel mentioned. The loop on the other end of the draught line is laid in the grooves around the keel of the buckle and is pressed firmly against this by the other thong as soon as the draught line is tightened.

Along the outer side of each runner runs a stout line, under which the load-lashing line is passed when the sledge is being lashed. To resist the pull of the load-lashing, a hole is bored in the upper edge of the runner about midway along the line; the line is passed through this hole to the inner side of the runner and over its upper edge back to the outer side.

On the small hunting sledges the cross-slats as a rule have no holes. They are simply lashed on by the thongs being passed over them in the same manner as among the Polar Eskimos.

As examples of the dimensions of some typical travelling sledges the following measurements are given from the Pâdlimiut at Eskimo Point.[56] The first mentioned of these is now in the Thule collection (P 28: 109; fig. 50).

| I | II | III | |

| Length | 574 cm | 984 cm | 760 cm |

| Breadth over all | 42 cm- | 42 cm- | 51,5 cm- |

| Thickness of runner at front | 4.9 cm- | 4.8 cm- | 5 cm- |

| Thickness of runner maximum | 8.3 cm- | 9 cm- | 9.8 cm- |

| Thickness of runner at rear | 3.4 cm- | 4 cm- | 4.5 cm- |

| Height of runner at front | 7 cm- | 4.8 cm- | 5.4 cm- |

| Height of runner maximum | 13 cm- | 14.7 cm- | 14.5 cm- |

| Height of runner at rear | 5.2 cm- | 4.5 cm- | 6 cm- |

| Distance from nose to maximum thickness of runner | 195 cm- | 234 cm- | 303 cm- |

| Distance from nose to first cross-slat | 166 cm- | 328 cm- | 254 cm- |

| Distance from nose to cross line supporting draught-line | 166 cm- | 20 cm- | 21 cm- |

| Number of cross-slats | 14 cm- | 24 cm- | 24 cm- |

The shortest travelling sledge I have seen belonged to a Hauneqtôrmio; it was not much longer than the sledges of the Polar and

Fig. 51.Small hunting sledge. (Sketch by the author).

Ponds Inlet Eskimos. Presumably the northern sledges on the whole have been shorter than the southern ones owing to the scarcity of wood. Although it can hardly have been a sledge from the Caribou Eskimos, it is significant that on the specimen found by Luke Foxe in 1631 at Cape Fullerton "The boards are some 9 or 10 foot long, 4 inches thicke".[57]

Fig. 51.Small hunting sledge. (Sketch by the author).

Ponds Inlet Eskimos. Presumably the northern sledges on the whole have been shorter than the southern ones owing to the scarcity of wood. Although it can hardly have been a sledge from the Caribou Eskimos, it is significant that on the specimen found by Luke Foxe in 1631 at Cape Fullerton "The boards are some 9 or 10 foot long, 4 inches thicke".[57]

The travelling sledges are never fitted with permanent shoes; but in the autumn a shoeing of peat, or rather peaty muck thickly mixed with half mouldered moss particles, is placed under them.[58] The muck is dug up at the water's edge of small ponds and thinned out in warm water till it has almost formed a kind of thick gruel. Big lumps of this are laid upon the lower edge of the runners with the bare hands, being smoothed and moulded so that the mass reaches a little way up the sides and at the same time stands out from the wood somewhat. The whole runner thus receives a section that can be compared with that of an upturned rail. Care is taken that each new lump put on merges smoothly into the preceding one, so that no irregularities are formed. Once this shoeing has been laid on in the autumn and has been allowed to freeze, it is preserved all the winter as far as possible; it is, however, rather brittle and breaks off in big pieces if the sledge runs against a stone. For this reason many Eskimos take with them on their journeys a bag of pulverised peat for repairs. We ourselves sometimes used porridge or custard.

Every morning before the day's journey begins, the peat shoeing must be furnished with a tire of ice. The sledge driver takes a mouthful of tepid water and squirts it out over a piece of skin, which should preferably be bearskin, and with this wipes the underside of the peat

Fig. 52.Sledge in spring, with peat shoeing protected against the sun by means of deerskin.

shoe. The water freezes almost immediately into a thin layer of freshwater ice, which almost neutralises all friction. It must not be quite cold when it is wiped on, as then the layer of ice falls off more readily. In emergencies. the Eskimos manage with urine. It is these ice-tires which enable the Central Eskimos to draw the tremendous sledge loads. The ice wears quickly, however. On long day's journeys it is as a rule necessary to stop at mid-day, melt snow and lay new ice under the runners. This is easily done now that the Eskimos have primus stoves. Presumably they have formerly (as for instance we know of the Aivilingmiut[59] carried a kind of field-bottle in their bosom, so that the water could remain thawed from the morning. The fact that some well-to-do Eskimos now have thermos flasks also indicates this.[60] Even a very short stretch of bare fresh-water ice on a lake, not to speak of stone, destroys the shoeing at once. Its advantages are so great, however, that a little extra manoeuvring of the sledge is never any trouble.

Fig. 52.Sledge in spring, with peat shoeing protected against the sun by means of deerskin.

shoe. The water freezes almost immediately into a thin layer of freshwater ice, which almost neutralises all friction. It must not be quite cold when it is wiped on, as then the layer of ice falls off more readily. In emergencies. the Eskimos manage with urine. It is these ice-tires which enable the Central Eskimos to draw the tremendous sledge loads. The ice wears quickly, however. On long day's journeys it is as a rule necessary to stop at mid-day, melt snow and lay new ice under the runners. This is easily done now that the Eskimos have primus stoves. Presumably they have formerly (as for instance we know of the Aivilingmiut[59] carried a kind of field-bottle in their bosom, so that the water could remain thawed from the morning. The fact that some well-to-do Eskimos now have thermos flasks also indicates this.[60] Even a very short stretch of bare fresh-water ice on a lake, not to speak of stone, destroys the shoeing at once. Its advantages are so great, however, that a little extra manoeuvring of the sledge is never any trouble.

It is worse in spring, when the warm weather begins to melt both the peat-layer and the ice-tiring. In the first place the peat-shoeing is made broader, and for a short time the expedient is used of hanging caribou skins down over the side of the sledge to protect it from the sun (fig. 52), and also one travels very early in the morning or late in the evening. Whenever a long stop is made and the sledge is unloaded, snow is shovelled over it so that the runners are entirely buried. When not even this helps any longer, the turf shoeing is knocked off. Out at the coast it is as a rule replaced by shoes of whale bones, which are brought from Marble Island where the whalers wintered. Walrus ivory gives still less friction; but it is so brittle that it easily breaks into pieces. I have never seen it used myself — perhaps owing to its relative expensiveness — but it is said to be in use. Steel shoes are now used in the interior. It would seem that there they were originally of hard wood.[61] The shoes are always a little broader than the runners and, like the peat shoes, they are furnished with a thin layer of ice as long as it is possible to do so, being wiped over with a layer of slush (of snow mixed with fresh water) which is allowed to freeze. Later on the sledge runs on the shoes alone.

Before a sledge is loaded, the cross-slats are covered with skins to prevent anything falling between them, and skins are laid over the load too. The thong with which these are lashed is fastened at the front to one of the two lines laid along the runners and then passed back over the load from side to side and down under these runner-lines, to be finally made fast at the rear with a double half-hitch.

Although the Caribou Eskimo sledges are, as will appear from the foregoing description, very similar to the West Greenland sledges, there are characteristic differences in the proportions, which again bring about another manner of running. On the West Greenland sledges the whole length of the runner, with the exception of the very upturned nose, rests upon the snow or the ice, and therefore the heaviest load is placed a little behind the middle. The length of the Caribou Eskimo sledge makes it necessary that the whole of the rear can swing freely if the sledge is to be capable of turning at all when it is loaded. Therefore the heaviest load is placed far to the front. where the foremost cross-slats are. The consequence is that the sledge must be turned by pushing in front, whereas the Greenland sledge is steered by means of the uprights, to which the lashing-thong is also made fast, the load being lashed from rear to front in contrast to the Caribou Eskimo method. The great length of the sledge and the difficulty of steering it is also one of the reasons why the Caribou Eskimos always travel in twos with the same sledge.

The West Greenland sledge is an excellent all-round type, its shortness and upturned runners making it suitable for travelling over steep mountain passes or in hummocky ice, while at the same time it can take as big a load as is necessary for the fairly short journeys of the Greenlanders.[62] The Caribou Eskimo sledge is adapted to the big loads of long journeys and to even terrain. It is not suitable for hummocky ice, both because it is too long and because the straight runners dig their noses down under the blocks of ice instead of gliding over them. When the sledge sticks and the dogs cannot move it, the driver must gather all the traces in his hand and, with an encouraging shout, suddenly release them. By means of this jerk the dogs often get the sledge on the move again. On unsafe ice the advantage of the great length of the sledge will often be outweighed by the correspondingly heavy load, and not even in the case of cracks does the length mean any advantage, because the dogs cannot jump over much wider cracks than a Greenland sledge can clear.

The dog harness [ano] is either of hairy caribou skin or, at the coast, of seal thong.[63] The latter material is strong, but spoils the dogs, because the thongs are too narrow. The harness of the leader dog is often decorated with gaily coloured strips of cloth, probably once fringes of white caribou skin such as are still seen among the Netsilik Eskimos. Among the Inland Pâdlimiut, Qaernermiut and Harvaqtôrmiut, the harness consists of two loops, crossed and sewn together where they cross, and at the rear united on a trace. By crossing the loops three openings appear, one for the dog's head and one for each of its forelegs. This harness is far superior to the barbaric West Siberian harness, but still is not particularly effective: the whole pull is concentrated on one single spot on the chest of the dog, for which reason it usually pulls with its head lowered, and the loops Image missingFig. 53.Dog harness and trace (a), and whip (b). are apt to creep up into the animal's arm-pits and rub there.

The construction among the Coast Pâdlimiut is a little less primitive and better for the dogs. Here the two loops are not crossed, but parallel, and, like a Greenland harness, connected by means of a neck strap and a breast strap. But they lack the belly-band of the Greenland harness and therefore are not so good as this, which distributes the pull over the whole of the breast. The neck and breast straps are as a rule spliced into the loops. But I have seen a deerskin harness on which the neck strap was formed of an arm from each loop. A common mistake in the harness of the Caribou Eskimos is that the loops are made too long and are therefore joined to the trace so far back that the harness is apt to slip down under the dog's tail. To remedy this a small cross-strap is often placed at the back between the loops. There is never a short draught strap at the back to which the trace is buckled as on a Greenland harness; the trace is, however, directly attached to the harness by splicing or by splicing and half-hitch combined.

The trace [qitunrᴀq] is preferably made of seal thong and at the rear ends either in a small simple loop or — rarely — in a heavy buckle of walrus ivory, antler, or even wood, which is placed on the draught-line of the sledge. A wooden buckle (P 28: 115) comes from Baker Lake. The traces vary in length, the leader dog having the longest; but they are all much longer than the Greenland traces. There is an advantage in both these features, as the dogs have more power over the sledge and, as travelling in hummocky ice is rare, the increased possibility that the traces will become entangled in the ice-blocks does not mean much. Nevertheless, as the dogs are spanned in fan-shape, each with its own trace, the traces always get ravelled up while travelling and have to be disentangled several times a day. For dogs, like human beings, have their sympathies and antipathies Image missingFig. 54.Swivel (a), and buckle for holding draught strap (b). and prefer to pull alongside certain chums, but on the other hand need a change now and then and, therefore, find a fresh place.

The following typical harness (P 28: 110) from the Pâdlimiut at Eskimo Point may be described: Harness of seal-thong, forming two parallel loops, each loose end first passing under the dog's forelegs, up over the breast and the shoulder and back to the thong and fastened by double splicing. Neck and breast straps, of four-ply babiche and seal-thong respectively, are passed through holes in the loops and, 19 cm from the rear end of the harness, a thin double tail-strap of babiche is fixed in a similar manner. Length from rear end to neck-strap 82 cm, neck-strap 10 cm, breast-strap 5 cm. The harness is spliced to a trace of seal thong, 458 cm long, ending at the rear in a spliced loop.

A similar set of harness (P 28: 112; fig. 53 a) is 83 cm long. The trace is sewn fast to the harness so that it forms the rearmost part of one of the loops. No tail strap. The trace, which has been repaired by splicing, is 786 cm long. On a third set (P 28: 111) like the first-named there is a splice instead of a tail strap. The harness is continued at the rear in a strap 76 cm long, to which the 540 cm trace is attached by a combination of splicing and half-hitch.

When the dogs are tied up, the trace is often fitted with a bone swivel which prevents the thong from curling. The swivel is always very simple and only consists of a rectangular plate with a hole in the middle, through which is thrust a peg with a head-shaped extension at one end and a hole at the other. The plate is made fast to the harness, the peg to the trace. From the Pâdlimiut, Eskimo Point, there is a specimen (P 28: 114) with a plate of ivory; it is pierced in every corner and out of a single piece of babiche two straps have been formed at each of the long sides, the strap on each of the short sides of the plate running along the opposite surface of the plate. The peg is of antler and at the rear has a hole with a strap of babiche. Plate 5 by 4.2 cm, peg 5.3 cm. A slightly bigger swivel (P 28: 113; fig. 54 a) from the same place is entirely of ivory. Swivels are never used while the sledge is running, because they cause the traces to Image missingFig. 55.Wooden snow-shoes. become entangled, and probably they would soon be broken against stones. When the snow on the ice has melted in the spring and the surface — especially of fresh-water ice — is hard and sharp as needles, the dogs are provided with small deerskin "boots".

The whip [iperautᴀq], like all the other sledge equipment, resembles those of both the other, continental Central Eskimos and of the Labrador Eskimos, whereas that of the Greenlanders is more slender and elegant.[64] A specimen (P 28:1 117) from the Pâdlimiut at Hikoligjuaq has a thick wooden shank [ipo], which is narrower at the handle and fitted at the butt end with a wrist strap of seal-thong. The free part of the shank is only 15 cm long, the handle 3.3 by 2.5 cm thick. The back end of the lash consists of several seal thongs continuously spliced into each other, reinforced by layers of babiche and plaited babiche cords, the whole bound with the same material. This portion has a length of 79 cm. Then follows a piece 41 cm long, consisting of the lash — a single, thick seal-thong — and a double strung babiche cord, which at the far end is passed through a slit in the lash; finally there is the extreme lash consisting of two lengths of thong spliced together. Total length 738 cm.

Another whip (P 28: 118; fig. 53 b) from the Pâdlimiut, Eskimo Point, likewise has a lash of seal-thong, continued at the back end in another seal-thong which is gradually spliced together with other five thongs. The lash is fastened to a wooden shank which is narrower at the handle, a seal-thong running back along each side of it and bound with a piece of babiche which runs through a hole in the butt end of the shank. This is also bound with babiche at the fore end. The length of the shank is 23.5 cm, thickness of the handle 3.3 by 1.8 cm. Total length of whip 763 cm.