The Ancient Geography of India

THE

ANCIENT GEOGRAPHY

OF

INDIA.

I.

A. Cunningham delt.

ANCIENT GEOGRAPHY

INDIA.

THE BUDDHIST PERIOD,

INCLUDING

THE CAMPAIGNS OP ALEXANDER, AND THE TRAVELS OF HWEN-THSANG.

ALEXANDER CUNNINGHAM,

Ui.JOB-GBirBBALj BOYAL ENGINEEBS (BENGAL BETIBBD).

" Venun et terrena demoDstratio intelligatar, Alezandri Magni vestigiiB insistamns." — PHnii Hist. Nat. vi. 17.

WITS TSIRTBBN MAPS.

LONDON :

TEUBNER AND CO., 60, PATERNOSTER ROW.

1871.

[All Sights reserved.']

TAYLOR AND CO., PRINTERS,

LITTLE QUEEN STREET, LINCOLN'S INN FIELDS.

MAJOR-GENERAL

SIR H. C. RAWLINSON, K.G.B.

ETC. ETC,

WHO HAS HIMSELF DONE SO MUCH

TO THROW LIGHT ON

THE ANCIENT GEOGRAPHY OP ASIA,

THIS ATTEMPT

TO ELUCIDATE A PARTIODLAR PORTION OF THE SUBJKT

IS DEDICATED

BY HIS FRIEND,

THE AUTHOR. PREFACE.

THE Geography of India may be conveniently divided into a few distinct sections, each broadly named after the prevailing religious and political character of the period which it embraces, as the Brahmanical, the Buddhist, and the Muhammadan.

The Brahmanical period would trace the gradual extension of the Aryan race over Northern India, from their first occupation of the Panjâb to the rise of Buddhism, and would comprise the whole of the Pre- historic, or earliest section of their history, during which time the religion of the Vedas was the pre- vailing belief of the country. The Buddhist period, or Ancient Geography of India, would embrace the rise, extension, and decline of the Buddhist faith, from the era of Buddha, to the conquests of Mahmud of Ghazni, during the greater part of which time Buddhism was the dominant reli- gion of the country.

The Muhammadan period, or Modern Geography of India, would embrace the rise and extension of the Muhammadan power, from the time of Mahmud of Ghazni to the battle of Plassey, or about 750 years, during which time the Musalmâns were the paramount sovereigns of India. The illustration of the Vedic period has already been made the subject of a separate work by M. Vivien de Saint-Martin, whose valuable essay[1] on this early section of Indian Geography shows how much interesting information may be elicited from the Hymns of the Vedas, by an able and careful investigator.

The second, or Ancient period, has been partially illustrated by H. H. Wilson, in his 'Ariana Antiqua,' and by Professor Lassen, in his 'Pentapotamia Indica.' These works, however, refer only to North-west India; but the Geography of the whole country has been ably discussed by Professor Lassen, in his large work on Ancient India,[2] and still more fully by M. de Saint-Martin, in two special essays,—the one on the Geography of India, as derived from Greek and Latin sources, and the other in an Appendix to M. Julien's translation of the Life and Travels of the Chinese pilgrim Hwen Thsang.[3] His researches have been conducted with so much care and success that few places have escaped identification. But so keen is his critical sagacity, that in some cases where the imperfection of our maps rendered actual identification quite impossible, he has indicated the true positions within a few miles.

For the illustration of the third, or Modern period, ample materials exist in the numerous histories of the Muhammadan States of India. No attempt, so far as I am aware, has yet been made to mark the limits of the several independent kingdoms that were established in the fifteenth century, during the troubles which followed the invasion of Timur. The history of this period is very confused, owing to the want of a special map, showing the boundaries of the different Muham- madan kingdoms of Delhi, Jonpur, Bengal, Malwa, Gujarât, Sindh, Multân, and Kulbarga, as well as the different Hindu States, such as Gwalior and others, which became independent about the same time.

I have selected the Buddhist period, or Ancient Geography of India, as the subject of the present inquiry, as I believe that the peculiarly favourable opportunities of local investigation which I enjoyed during a long career in India, will enable me to de- termine with absolute certainty the sites of many of the most important places in India.

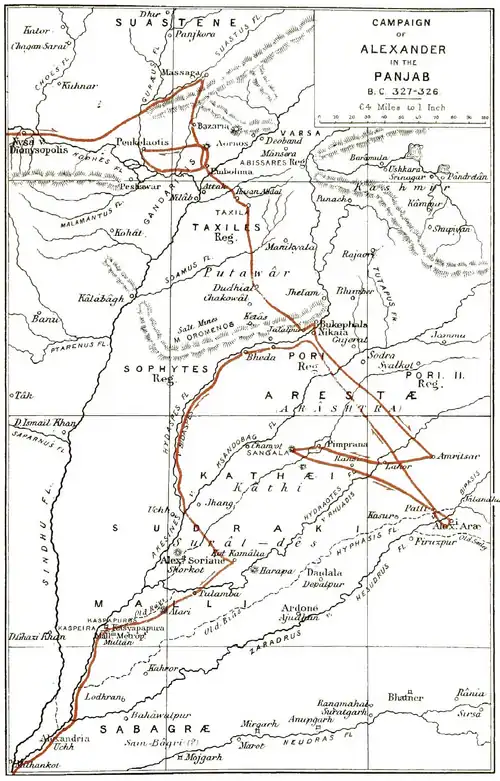

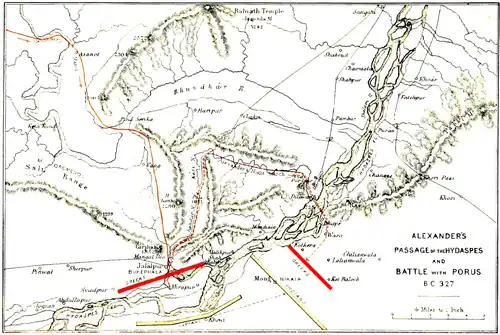

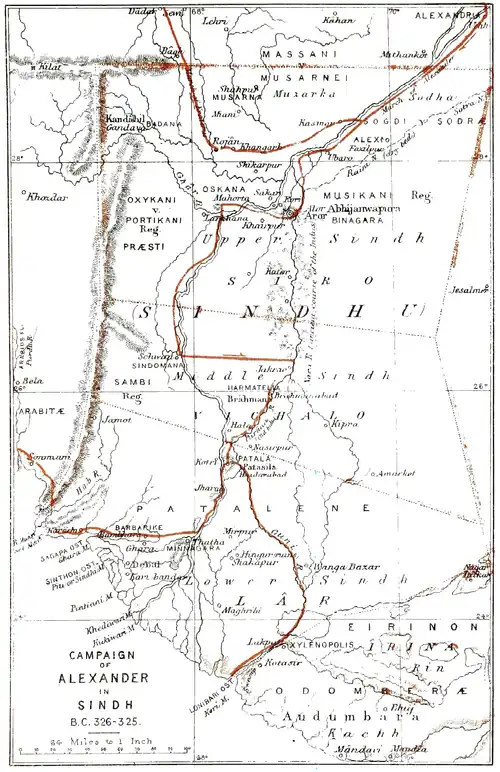

My chief guides for the period which I have under- taken to illustrate, are the campaigns of Alexander in the fourth century before Christ, and the travels of the Chinese pilgrim, Hwen Thsang, in the seventh century after Christ. The pilgrimage of tnis Chinese priest forms an epoch of as much interest and import- ance for the Ancient History and Geography of India, as the expedition of Alexander the Great. The actual campaigns of the Macedonian conqueror were confined to the valley of the Indus and its tributaries; but the information collected by himself and his companions, and by the subsequent embassies and expeditions of the Seleukide kings of Syria, embraced the whole valley of the Ganges on the north, the eastern and western coasts of the peninsula, and some scattered notices of the interior of the country. This infor- mation was considerably extended by the systematic inquiries of Ptolemy, whose account is the more valu able, as it belongs to a period just midway* between the date of Alexander and that of Hwen Thsang, at which time the greater part of North-west India had been subjected by the Indo-Scythians.

With Ptolemy, we lose the last of our great classi- cal authorities; and, until lately, we were left almost entirely to our own judgment in connecting and arranging the various geographical fragments that lie buried in ancient inscriptions, or half hidden in the vague obscurity of the Purânas. But the fortunate discovery of the travels of several Chinese pilgrims in the fifth, sixth, and seventh centuries of the Chris- tian era, has thrown such a flood of light upon this hitherto dark period, that we are now able to see our way clearly to the general arrangement of most of the scattered fragments of the Ancient Geography of India.

The Chinese pilgrim Fa-Hian was a Buddhist priest, who travelled through India from the banks of the Upper Indus to the mouth of the Ganges, between the years 399 and 413 A.D. Unfortunately his journal is very concise, and is chiefly taken up with the de- scription of the sacred spots and objects of his reli- gion, but as he usually gives the bearings and dis- tances of the chief places in his route, his short notices are very valuable. The travels of the second Chinese pilgrim, Sung-Yun, belong to the year 502 A.D., but as they were confined to the Kabul valley and North- west Panjâb, they are of much less importance, more

- Campaign of Alexander, B.C.330, and Ptolemy's 'Geography,' A.D.

15C, or 480 years later. Beginning of Hwen Thisang's travels in India, A.D. 630, or just 480 years after Ptolemy. especially as his journal is particularly meagre in geographical notices.*

The third Chinese pilgrim, Hwen Thsang, was also a Buddhist priest, who spent nearly fifteen years of his life in India in studying the famous books of his religion, and in visiting all the holy places of Buddhism. For the translation of his travels we are wholly in- debted to M. Stanislas Julien, who with unwearied resolution devoted his great abilities for no less than twenty years to the acquirement of the Sanskrit and Chinese languages for this special purpose. The period of Hwen Thsang's travels extended from A.D. 629 to 645. During that time he visited most of the great cities throughout the country, from Kabul and Kashmir to the mouths of the Ganges and Indus, and from Nepal to Kanchipura near Madras. The pilgrim entered Kabul from the north-west, viâ Bamian, about the end of May, A.D. 630, and after many wanderings and several long halts, crossed the Indus at Ohind in April of the following year. He spent several months in Taxila for the purpose of visiting the holy places of Buddhism, and then proceeded to Kashmir, where he stayed for two whole years to study some of the more learned works of his religion. On his journey east- ward he visited the ruins of Sangala, so famous in the history of Alexander, and after a stay of fourteen months in Chinapati, and of four months in Jalandhara, for the further study of his religion he crossed the Satlej in the autumn of A.D. 635. From thence his onward course was more devious, as several times he

- The travels of both of these pilgrims have been most carefully

and ably translated by the Rev. S. Beal.

† Max Müller's ‘Buddhism and Buddhist Pilgrims,' p. 30. retraced his steps to visit places which had been left behind in his direct easterly route. Thus, after having reached Mathura he returned to the north-west, a dis- tance of 200 miles to Thanesar, from whence he re- sumed his easterly route viâ Srughna on the Jumna, and Gangadwára on the Ganges to Ahichhatra, the capital of Northern Panchála, or Rohilkhand. He next recrossed the Ganges to visit the celebrated cities of Sankisa, Kanoj, and Kosámbi in the Doâb, and then turning northward into Oudh he paid his devotions at the holy places of Ayodhya and Srávasti. From thence he resumed his easterly route to visit the scenes of Buddha's birth and death at Kapilavastu and Kusina- gara; and then once more returned to the westward to the holy city of Banaras, where Buddha first began to teach his religion. Again resuming his easterly route he visited the famous city of Vaisáli in Tirhût, from whence he made an excursion to Nepal, and then re- tracing his steps to Vaisâli he crossed the Ganges to the ancient city of Pataliputra, or Palibothra. From thence he proceeded to pay his devotions at the nu- merous holy places around Gaya, from the sacred fig- tree at Bodh Gaya, under which Buddha sat for five years in mental abstraction, to the craggy hill of Giriyek, where Buddha explained his religious views to the god Indra. He next visited the ancient cities of Kuságarapura and Rajagriha, the early capitals of Magadha, and the great monastery of Nalanda, the most famous seat of Buddhist learning throughout India, where he halted for fifteen months to study the Sanskrit language. Towards the end of A.D. 638 he resumed his easterly route, following the course of the Ganges to Modagiri and Champa, and then crossing the river to the north he visited Paundra Varddhana, or Pubna, and Kámarúpa, or Assam.

Having now reached the most easterly district of India he turned towards the south, and passing through Samatata, or Jessore, and Támralipti, or Tamluk, he reached Odra, or Orissa, early in A.D. 639. Continuing his southerly route he visited Ganjam and Kalinga, and then turning to the north-west he reached Kosala, or Berar, in the very heart of the peninsula. Then re- suming his southerly course he passed through Andhra, or Telingâna to Dhanakakata, or Amaravati on the Kistna river, where he spent many months in the study of Buddhist literature. Leaving this place early in A.D. 640 he pursued his southerly course to Kanchipura, or Conjeveram, the capital of Dravida, where his further progress in that direction was stopped by the intelligence that Ceylon was then in a very troubled state consequent on the recent death of the king. This statement is specially valuable for the purpose of verifying the dates of the pilgrim's arrival at different places, which I have calculated according to the actual distances travelled and the stated duration of his halts.* Now the troubled state of Ceylon fol- lowed immediately after the death of Raja Buna-Mu- galán, who was defeated and killed in A.D. 639; and it is only reasonable to infer that the Ceylonese monks, whom the pilgrim met at Kânchipura, must have left their country at once, and have reached that place early in A.D. 640, which accords exactly with my calculation of the traveller's movements.

From Dravida Hwen Thsang turned his steps to the north, and passing through Konkana and Ma-

- See Appendix A for the Chronology of Hwen Thsang's Travels.

háráshtra arrived at Bhároch on the Narbada, from whence, after visiting Ujain and Balabhi and several smaller states, he reached Sindh and Multân towards the end of A.D. 641. He then suddenly returned to Magadha, to the great monasteries of Nálanda and Tiladhaka, where he remained for two months for the solution of some religious doubts by a famous Bud- dhist teacher named Prajnabhadra. He next paid a second visit to Kamrup, or Assam, where he halted for a month. Early in A.D. 643 he was once more at Pátaliputra, where he joined the camp of the great king Harsha Varddhana, or Silâditya, the paramount sovereign of northern India, who was then attended by eighteen tributary princes, for the purpose of add- ing dignity to the solemn performance of the rites of the Quinquennial Assembly. The pilgrim marched in the train of this great king from Páṭaliputra through Prayaga and Kosambi to Kanoj. He gives a minute description of the religious festivals that were held at these places, which is specially interesting for the light which it throws on the public performance of the Buddhist religion at that particular period. At Kanoj he took leave of Harsha Varddhana, and re- sumed his route to the north-west in company with Raja Udhita of Jalandhara, at whose capital he halted for one month. In this part of his journey his pro- gress was necessarily slow, as he had collected many statues and a large number of religious books, which he carried with him on baggage elephants.* Fifty of his manuscripts were lost on crossing over the Indus at Utakhanda, or Ohind. The pilgrim himself forded the river on an elephant, a feat which can only

- M. Julien's Hiouen Thisang,' i. 262, 263.

be performed during the months of December, Janu- ary and February, before the stream begins to rise from the melted snows. According to my calcula- tions, he crossed the Indus towards the end of A.D. 643. At Utakhanda he halted for fifty days to obtain fresh copies of the manuscripts which had been lost. in the Indus, and then proceeded to Lamghân in com- pany with the King of Kapisa. As one month was occupied in this journey, he could not have reached Lamghâm until the middle of March, A.D. 644, or about three months before the usual period, when the passes of the Hindu Kush become practicable. This fact is sufficient to account for his sudden journey of fifteen days to the south to the district of Falana, or Banu, from whence he reached Kapisa viâ Kâbul and Ghazni about the beginning of July. Here he again halted to take part in a religious assembly, so that he could not have left Kapisa until about the middle of July A.D. 644, or just fourteen years after his first entry into India from Bamian. From Kapisa he passed up the Panjshir valley and over the Khâwak Pass to Anderâb, where he must have arrived about the end of July. It was still early for the easy cross- ing of this snowy pass, and the pilgrim accordingly notices the frozen streams and beds of ice which he encountered on his passage over the mountain. To- wards the end of the year he passed through Kâsh- gâr, Yârkand, and Kotan, and at last, in the spring of a.d. 645, he arrived in safety in the western capital of China.

This rapid survey of Hwen Thsang's route is suffi- cient to show the great extent and completeness of his Indian travels, which, as far as I am aware, have never been surpassed. Buchanan Hamilton's survey of the country was much more minute, but it was limited to the lower provinces of the Ganges in northern India and to the district of Mysore in southern India. Jacquemont's travels were much less restricted; but as that sagacious Frenchman's observations were chiefly confined to geology and botany and other scientific subjects, his journeyings in India have added but little to our knowledge of its geography. My own travels also have been very ex- tensive throughout the length and breadth of northern India, from Peshawar and Multan near the Indus, to Rangoon and Prome on the Irawadi, and from Kash- mir and Ladâk to the mouth of the Indus and the banks of the Narbada. Of southern India I have seen nothing, and of western India I have seen only Bombay, with the celebrated caves of Elephanta and Kanhari. But during a long service of more than thirty years in India, its early history and geography have formed the chief study of my leisure hours; while for the last four years of my residence these subjects were my sole occupation, as I was then em- ployed by the Government of India as Archæological Surveyor, to examine and report upon the antiquities of the country. The favourable opportunity which I thus enjoyed for studying its geography was used to the best of my ability; and although much still re- mains to be discovered I am glad to be able to say that my researches were signally successful in fixing the sites of many of the most famous cities of ancient India. As all of these will be described in the fol- lowing account, I will notice here only a few of the more prominent of my discoveries, for the purpose of PEEFAC'E. XV

showing that I have not undertaken the present work without much previous preparation.

1. Aornos^ the famous rock fort captured by Alex- ander the Great.

2. Taxila, the capital of the north-western Panjab.

3. Sangala^ the hill fortress in the central Panjab, captured by Alexander.

4. Sruglma^ a famous city on the Jumna.

5. Ahiclihatra, the capital of northern Panchala.

6. Bairdtj the capital of Matsya, to the south of Delhi.

7. Sankisa, near Kanoj, famous as the place of Buddha's descent from heaven.

8. Srdoasti, on the Eapti, famous for Buddha's preaching.

9. Kosdmbi^ on the Jumna, near Allahabad.

10. Padmavati, of the poet Bhavabhuti.

11. Vaisdli, to the north of Patna.

12. Ndlanda, the most famous Buddhist monastery

in all India. CONTENTS.

Preface |

Page |

General Description |

1 |

NORTHERN INDIA |

15 |

| I. | Kaufu, or Afghanistan |

17 |

| 1. | Kapisene, or Opiân |

18 |

Karsana, or Tetragonis, or Begram |

26 |

Other cities of Kapisene |

31 |

| 2. | Kophene, or Kabul |

32 |

| 3. | Arachosia, or Ghazni |

39 |

| 4. | Lamghân |

42 |

| 5. | Nagarahâra, or Jalalabad |

43 |

| 6. | Gândhâra, or Parashâwar |

47 |

Pushkalâvati, or Peukelaotis |

49 |

Varusha, or Paladheri |

49 |

Utakhanda, or Embolim (Ohind) |

52 |

Sålâtura, or Lahor. |

57 |

Aornos, or Rânigat |

58 |

Parashâwara, or Peshawar |

78 |

| 7. | Udyâna, or Swât |

81 |

| 8. | Bolor, or Balti |

83 |

| 9. | Falana, or Banu |

84 |

| 10. | Opokien, or Afghanistan (Loi, or Roh) |

87 |

| II | KASHMIR |

89 |

| 1. | Kashmir (province) |

90 |

| 2. | Urasa |

103 |

| 3. | Taxila, or Takshasila |

104 |

Minikyâla |

78 |

| 4. | Singhapura, or Ketâs |

124 |

| 5. | Punacha, or Punach |

128 |

| 6. | Rajapuri, or Rajaori |

129 |

Hill-states of the Panjâb |

129 |

Jâlandhara |

130 |

Champa, or Chamba |

136 |

Kullu |

141 |

Mandi and Sukhet |

142 |

Nirpâr, or Pathâniya |

143 |

Satadru |

78 |

| VI | TAKI, OR PANJAB |

42 |

| 1. | Tâki, or Northern Panjâb |

47 |

Jobnâthnagar, or Bhira |

155 |

Bukephala, or Jalâlpur |

159 |

Nikaa, or Mong |

177 |

Gujarât |

179 |

Sakala, or Sangala |

179 |

II.

A. Cunningham Del.

THE

ANCIENT GEOGRAPHY OF INDIA.

FROM the accounts of the Greeks it would appear that the ancient Indians had a very accurate knowledge of the true shape and size of their country. According to Strabo,[4] Alexander "caused the whole country to be described by men well acquainted with it;" and this account was afterwards lent to Patrokles by Xenokles, the treasurer of the Syrian kings. Patrokles himself held the government of the north-east satrapies of the Syrian empire under Seleukus Nikator and Antiochus Soter, and the information which he collected regarding India and the Eastern provinces, has received the approbation of Eratosthenes and Strabo for its accuracy. Another account of India was derived from the register of the Stathmi,[5] or "Marches" from place to place, which was prepared by the Macedonian Amyntas, and which was confirmed by the testimony of Megasthenes, who had actually visited Palibotlira as the ambassador of Seleukus Nikator. On the authority of these documents, Eratosthenes and other writers have described India as a rhomboid, or unequal quadrilateral, in shape, with the Indus on the west, the mountains on the north, and the sea on the east and south.[6] The shortest side was on the west, which Patrokles estimated at 12,000 stadia, and Eratosthenes at 13,000 stadia.[7] I All the accounts agree that the course of the Indus from Alexander's Bridge to the sea was 10,000 stadia, or 1149 British miles; and they differ only as to the estimated distance of the snowy mountains of Caucasus or Paropamisus above the bridge. The length of the country was reckoned from west to east, of which the part extending from the Indus to Palibothra had been measured by schœni along the royal road, and was 10,000 stadia, or 1149 British miles in length. From Palibothra to the sea the distance was estimated at 6000 stadia, or 689 British miles; thus making the whole distance from the Indus to the mouth of the Ganges 16,000 stadia,[8] or 1838 British miles. According to Pliny,[9] the distance of Palibothra from the mouth of the Ganges was only 637.5 Roman miles; but his numbers are so corrupt that very little dependence can be placed upon them. I would, therefore, increase his distance to 737.5 Roman miles, which are equal to 678 British miles. The eastern coast from the mouth of the Ganges to Cape Comorin was reckoned at 16,000 stadia, or 1838 British miles; and the southern (or south-western) coast, from Cape Comorin to the mouth of the Indus at 3000 stadia more[10] than the northern side, or 19,000 stadia, equivalent to 2183 British miles.

The close agreement of these dimensions, given by Alexander's informants, with the actual size of the country is very remarkable, and shows that the Indians, even at that early date in their history, had a very accurate knowledge of the form and extent of their native land.

On the west, the course of the Indus from Ohind, above Attok, to the sea is 950 miles by land, or about 1200 miles by water. On the north, the distance from the banks of the Indus to Patna, by our military route books, is 1143 miles, or only 6 miles less than the measurement of the royal road from the Indus to Palibothra, as given by Strabo on the authority of Megasthenes. Beyond this, the distance was estimated by the voyages of vessels on the Ganges at 6000 stadia, or 689 British miles, which is only 9 miles in excess of the actual length of the river route. From the mouth of the Ganges to Cape Comorin the distance, measured on the map, is 1600 miles, but taking into account the numerous indentations of the coast-line, the length should probably be increased in the same proportion as road distance by one-sixth. This would make the actual length 1866 miles. From Cape Comorin to the mouth of the Indus there is a considerable discrepancy of about 3000 stadia, or nearly 350 miles, between the stated distance and the actual measurement on the map. It is probable that the difference was caused by including in the estimate the deep indentations of the two great gulfs of Khambay and Kachh, which alone would be sufficient to account for the whole, or at least the greater part, of the discrepancy.

This explanation would seem to be confirmed by the computations of Megasthenes, who "estimated the distance from the southern sea to the Caucasus at 20,000 stadia,"[11] or 2298 British miles. By direct measurement on the map the distance from Cape Comorin to the Hindu Kush is about 1950 miles,[12] which, converted into road distance by the addition of one-sixth, is equal to 2275 miles, or within a few miles of the computation of Megasthenes. But as this distance is only 1000 stadia greater than the length of the coast-line from Cape Comorin to the mouth of the Indus, as stated by Strabo, it seems certain that there must be some mistake in the length assigned to the southern (or south-western) coast. The error would be fully corrected by making the two coast-lines of equal length, as the mouths of the Ganges and Indus are about equidistant from Cape Comorin. According to this view, the whole circuit of India would be 61,000 stadia; and this is, perhaps, what is intended by Diodorus,[13] who says that "the whole extent of India from east to west is 28,000 stadia, and from north to south 32,000 stadia," or 60,000 stadia altogether.

At a somewhat later date the shape of India is described in the 'Mahâbhârata' as an equilateral triangle, which was divided into four smaller equal triangles.[14] The apex of the triangle is Cape Comorin, and the base is formed by the line of the Himalaya mountains. No dimensions are given, and no places are mentioned; but, in fig. 2 of the small maps of India in the accompanying plate, I have drawn a small equilateral triangle on the line between Dwâraka, in Gujarat, and Ganjam on the eastern coast. By repeating this small triangle on each of its three sides, to the north-west, to the north-east, and to the south, we obtain the four divisions of India in one large equilateral triangle. The shape corresponds very well with the general form of the country, if we extend the limits of India to Ghazni on the north-west, and fix the other two points of the triangle at Cape Comorin, and Sadiya in Assam. At the presumed date of the composition of the 'Mahâbhârata,' in the first century A.D., the countries immediately to the west of the Indus belonged to the Indo-Scythians, and therefore may be included very properly within the actual boundaries of India.

Another description of India is that of the Nava-Khanda, or Nine-Divisions, which is first described by the astronomers Parâsara and Varâha-Mihira, although it was probably older than their time,[15] and was wards adopted by the authors of several of the Purânas. According to this arrangement, Pânchâla was the chief district of the central division, Magadha of the east, Kalinga of the south-east, Avanta of the south, Anarta of the south-west, Sindhu-Sauvira of the west, Hârahaura of the north-west, Madra of the north, and Kauninda of the north-east.[16] But there is a discrepancy between this epitome of Varâha and his details, as Sindhu-Sauvira is there assigned to the south-west, along with Anarta.[17] This mistake is certainly as old as the eleventh century, as Abu Rihâm has preserved the names of Varâha's abstract in the same order as they now stand in the 'Brihat-Sanhitâ.'[18] These details are also supported by the 'Mârkandeya Purâna,' which assigns both Sindhu-Sauvira and Anarta to the south-west.[19]

I have compared the detailed lists of the 'Brihat-Sanhitâ' with those of the Brahmânda, Mârkandeya, Vishnu, Vâyu, and Matsya Purânas; and I find that, although there are sundry repetitions and displacements of names, as well as many various readings, yet

[20] Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/39 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/40 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/41 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/42 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/43 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/44 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/45 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/46 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/47 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/48 III.

A. Cunningham delt.

IV.

A. Cunningham delt.

V.

A. Cunningham delt.

VI.

A. Cunningham delt.

VII.

VIII.

A. Cunningham delt.

line it is not more than 16 miles. The circuit of Tse- kia was about 20 li, or upwards of three miles, which agrees sufficiently well with my measurement of the ruins of Asarur at 15,600 feet, or just three miles. At the time of Hwen Thsang's visit there were ten mo- nasteries, but very few Buddhists, and the mass of the people worshipped the Brahmanical gods. To the north-east of the town at 10 li, or nearly 2 miles, there was a stupa of Asoka, 200 feet in height, which marked the spot where Buddha had halted, and which was said to contain a large quantity of his relics. This stupa may, I think, be identified with the little mound of Sâlár, near Thata Syadon, just two miles to the north of Asarur.

Ran-si, or Nara-Sinha.

On leaving Tse-kia, Hwen Thsang travelled east- ward to Na-lo-Seng-ho, or Nára-Sinha, beyond which place he entered the forest of Po-lo-she, or Pilu trees (Salvadora Persica), where he encountered the bri- gands, as already related. This town of Nara-Sinha is, I believe, represented by the large ruined mound of Ran-Si, which is situated 9 miles to the south of Shekohpura, and 25 miles to the east-south-east of Asarur, and about the same distance to the west of Lahor.* Si, or Sih, is the usual Indian contraction for Sinh, and Ran is a well-known interchange of pro- nunciation with Nar, as in Ranod for Narod, a large town in the Gwalior territory, about 35 miles to the south of Narwar, and in Nakhlor for Lakhnor, the capital of Katehar, or Rohilkhand. In Ransi, there- fore, we have not only an exact correspondence of

- See Map No. VI. Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/238 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/239 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/240

Amakapis, to the west of Râvi, and in the immediate neighbourhood of Labokla, or Lahor.*

The mound of Amba is 900 feet square, and from 25 to 30 feet in height; but as the whole of the sur- rounding fields, for a breadth of about 600 feet, are covered with broken pottery, the full extent of the ancient town may be taken at not less than 8000 feet, or upwards of 3 miles in circuit. The mound itself is covered with broken bricks of large size, amongst which I discovered several pieces of carved brick. I found also one piece of grey sandstone, and a piece of speckled iron ore, similar to that of Sangala, and of the Karâna hills. According to the statements of the people, the place was founded by Raja Amba 1800 or 1900 years ago, or just about the beginning of the Christian era. This date would make the three brothers contemporary with Hushka, Jushka, and Kanishka, the three great kings of the Yuchi, or Kushán race of Indo-Scythians, with whom I am, on other grounds, inclined to identify them. At present, however, I am not prepared to enter upon the long discussion which would be necessary to establish their identity. Loháwar, or Láhor.

The great city of Lahor, which has been the capital of the Panjâb for nearly nine hundred years, is said to have been founded by Lava, or Lo, the son of Râma, after whom it was named Loháwar. Under this form it is mentioned by Abu Rihân; but the present form

- The identification of Ptolemy's Labokla with Lahor was first made

in Kiepert's Map of India, according to Ptolemy, which accompanied Lassen's 'Indische Alterthumskunde.' It has since been confirmed by the researches of Mr. T. H. Thornton, the author of the 'History and Antiquities of Lahor.' Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/242 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/243 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/244 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/245 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/246 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/247 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/248 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/249 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/250 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/251 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/252 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/253 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/254 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/255 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/256 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/257 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/258 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/259 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/260 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/261 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/262 and stones, was immediately turned into sugar, whence his name of Shakar-ganj, or “Sugar-store." This mi- raculous power is recorded in a well-known Persian couplet :-

"Sang dar dast o guhar gardad, Zahar dar kám o shakar gardad: "

which may be freely rendered:

"Stones in his hand are changed to money (jewels), And poison in his mouth to honey (sugar).”

From another memorial couplet we learn that he died in A.H. 664, or A.D. 1265-66, when he was 95 lunar years of age. But as the old name of Ajudhan is the only one noted by Ibn Batuta in A.D. 1334, and by Timur's historian in a.d. 1397, it seems probable that the present name of Pák-pattan is of comparatively recent date. It is, perhaps, not older than the reign of Akbar, when the saint's descendant, Núr-ud-din, revived the former reputation of the family by the success of his prayers for an heir to the throne.

4. MULTAN PROVINCE.

The southern province of the Panjâb is Multân. According to Hwen Thsang it was 4000 li, or 667 miles, in circuit, which is so much greater than the tract actually included between the rivers, that it is almost certain the frontier must have extended beyond them. In the time of Akbar no less than seventeen districts, or separate parganahs, were attached to the province of Multân, of which all those that I can identify, namely, Uch, Diráwal, Moj, and Marot, are to the east of the Satlej. These names are sufficient to show that the eastern frontier of Multân formerly extended beyond the old bed of the Ghagar river, to the verge of the Bikaner desert. This tract, which now forms the territory of Bahawalpur, is most effectu- ally separated from the richer provinces on the east by the natural barrier of the Great Desert. Under a strong government it has always formed a portion of Multân; and it was only on the decay of the Muham- madan empire of Delhi that it was made into a separate petty state by Bahawal Khân. I infer, therefore, that in the seventh century the province of Multân must have included the northern half of the present territory of Bahawalpur, in addition to the tract lying between the rivers. The northern frontier has already been defined as extending from Dera Din-panáh, on the Indus, to Pák-pattan on the Satlej, a distance of 150 miles. On the west the frontier line of the Indus, down to Khânpur, is 160 miles. On the east, the line from Pâk-pattan to the old bed of the Ghagar river, is 80 miles; and on the south, from Khânpur to the Ghagar, the distance is 220 miles. Altogether, this frontier line is 610 miles. If Hwen Thsang's estimate was based on the short kos of the Panjâb, the circuit will be only 3 of 667 miles, or 437 miles, in which case the province could not have extended beyond Mithankot on the south.

In describing the geography of Multân it is neces- sary to bear in mind the great changes that have taken place in the courses of all the large rivers that flow through the province. In the time of Timur and Akbar the junction of the Chenâb and Indus took place opposite Uchh, 60 miles above the present con- fluence at Mithankot. It was unchanged when Rennell wrote his 'Geography of India,' in A.D. 1788, and still later, in 1796, when visited by Wilford's surveyor, Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/265 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/266 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/267 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/268 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/269 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/270 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/271 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/272 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/273 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/274 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/275 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/276 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/277 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/278 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/279 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/280 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/281 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/282 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/283 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/284 that Multân was commanded by a citadel, which had four gates, and was surrounded by a ditch. I infer, therefore, that Muhammad Kasim may have captured Multân in the same way that Cyrus captured Babylon, by the diversion of the waters which flowed through the city into another channel. In this way he could have entered the city by the dry bed of the river, after which it is quite possible that the garrison of the citadel may have been forced to surrender from want of water. At the present day there are several wells in the fortress, but only one of them is said to be ancient; and one well would be quite insufficient for the supply even of a small garrison of 5000 men. Kahror.

The ancient town of Kahror is situated on the southern bank of the old Biâs river, 50 miles to the south-east of Multân, and 20 miles to the north-east of Bahawalpur. It is mentioned as one of the towns which submitted to Chach* after the capture of Multân in the middle of the seventh century. But the interest attached to Kahror rests on its fame as the scene of the great battle between Vikramaditya and the Sakas, in A.D. 79. Abu Rihân describes its position as situated between Multân and the castle of Loni. The latter place is most probably intended for Ludhan, an ancient town situated near the old bed of the Satlej river, 44 miles to the east-north-east of Kahror, and 70 miles to the east-south-east of Multân. Its position is therefore very nearly halfway between Multân and Ludhan, as described by Abu Rihân.

- Lieut. Postans, Journ. Asiat. Soc., Bengal, 1838, p. 95, where the

translator reads Karud, 2,,, instead of „S, Karor.

R Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/286 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/287 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/288 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/289 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/290 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/291 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/292 IX.

A. Cunningham delt.

Lohána, all of which will be discussed presently, as they would appear to correspond with the divisions noted by Hwen Thsang.

Upper Sindh.

The single principality of Upper Sindh, which is now generally known as Siro, that is the "Head or Upper" division, is described as being 7000 li, or 1167 miles, in circuit, which is too great, unless, as is very probable, it comprised the whole of Kachh Gan- dâva on the west. This was, no doubt, always the case under a strong government, which that of Chach's predecessor is known to have been. Under this view Upper Sindh would have comprised the present dis- tricts of Kachh-Gandava, Kâhan, Shikârpur, and Larkâna to the west of the Indus, and to the east those of Sabzalkot and Khairpur. The lengths of the frontier lines would, therefore, have been as follows:- on the north 340 miles; on the west 250 miles on the east 280 miles, and on the south 260 miles; or altogether 1030 miles, which is a very near approxi- mation to the estimate of Hwen Thsang.

In the seventh century the capital of the province was named Pi-chen-po-pu-lo, which M. Julien tran- scribes as Vichava-pura. M. Vivien de St. Martin, however, suggests that it may be the Sanskrit Vichála- pura, or city of "Middle Sindh," which is called Vicholo by the people. But the Sindhi and Panjabi Vich and the Hindi Bích, or "middle," are not derived from the Sanskrit, which has a radical word of its own, Madhya, to express the same thing. If Hwen Thsang had used the vernacular terms, his name might have been rendered exactly by the Hindi Bichwá-pur, or "Middle City; ;" but as he invariably uses the Sanskrit forms, I think that we must rather look to some pure Sanskrit word for the original of his Pi- chen-po-pu-lo. Now we know from tradition, as well as from the native historians, that Alor was the capital of Sindh both before and after the period of Hwen Thsang's visit; this new name, therefore, must be only some variant appellation of the old city, and not that of a second capital. During the Hindu period it was the custom to give several names to all the larger cities, —as we have already seen in the case of Multân. Some of these were only poetical epithets; as Kusuma- pura, or "Flower City" applied to Pâtaliputra, and Padmavati, or, "Lotus Town" applied to Narwar; others were descriptive epithets as Varanasi, or Ba- náras, applied to the city of Kâsi, to show that it was situated between the Varana and dsi rivulets; and Kányakubja, the "hump-backed maiden," applied to Kanoj, as the scene of a well-known legend. The difference of name does not, therefore, imply a new capital, as it may be only a new appellation of the old city, or perhaps even the restoration of an old name which had been temporarily supplanted. It is true that no second name of Alor is mentioned by the his- torians of Sindh ; but as Alor was actually the capital in the time of Hwen Thsang, it would seem to be quite certain that his name of Pi-chen-po-pu-lo is only another name for that city.

It is of importance that this identification should be clearly established, as the pilgrim places the capital to the west of the Indus, whereas the present ruins of Alor or Aror are to the east of the river. But this very difference confirms the accuracy of the identifi cation, for the Indus formerly flowed to the east of Alor, down the old channel, now called Nára, and the change in its course did not take place until the reign of Raja Dâhir,* or about fifty years after Hwen Thsang's visit. The native histories attribute the de- sertion of Alor by the Indus to the wickedness of Raja Dâhir; but the gradual westing of all the Panjâb rivers which flow from north to south, is only the natural result of the earth's continued revolution from west to east, which gives their waters a permanent bias towards the western banks. The original course of the Indus was to the east of the Alor range of hills; but as the waters gradually worked their way to the westward, they at last turned the northern end of the range at Rori, and cut a passage for themselves through the gap in the limestone rocks between Rori and Bha- kar. As the change is assigned to the beginning of Dâhir's reign, it must have taken place shortly after his accession in a.d. 680;—and as Muhammad Kasim,

just thirty years later, was obliged to cross the Indus to reach Alor, it is certain that the river was perma- nently fixed in its present channel before A.D. 711. The old bed of the Indus still exists under the name of Nâra, and its course has been surveyed from the ruins of Alor to the Ran of Kachh. From Alor to Jakrao, a distance of 100 miles, its direction is nearly due south. It there divides into several channels, each bearing a separate name. The most easterly

- Postans, Journ. Asiat. Soc. Bengal, 1838, p. 103.

† All streams that flow from the poles towards the equator work gradually to the westward, while those that flow from the equator towards the poles work gradually to the eastward. These opposite effects are caused by the same difference of the earth's polar and equatorial velocities which gives rise to the trade winds. channel, which retains the name of Nára, runs to the south-east by Kipra and Umrkot, near which it turns to the south-west by Wanga Bazar and Romaka Bazar, and is there lost in the great Ran of Kachh. The most westerly channel, which is named Purána, or the "Old River," flows to the south-south-west, past the ruins of Brahmanabad and Nasirpur to Hai- darabad, below which it divides into two branches. Of these, one turns to the south-west and falls into the present river 15 miles below Haidarabad and 12 miles above Jarak. The other, called the Guni, turns to the south-east and joins the Nâra above Romaka Bazar. There are at least two other channels between the Purâna and the Nâra, which branch off just below Jakrao, but their courses are only partially known. The upper half of the old Nâra, from Alor to Jakrao, is a dry sandy bed, which is occasionally filled by the flood waters of the Indus. From its head down to Jamiji it is bounded on the west by a continuation of the Alor hills, and is generally from 200 feet to 300 feet wide and 20 feet deep. From Jâmiji to Jakrao, where the channel widens to 600 feet with the depth of 12 feet, the Nâra is bounded on both sides by broad ranges of low sand-hills. Below Jakrao the sand-hills on the western bank suddenly terminate, and the Nâra, spreading over the alluvial plains, is divided into two main branches, which grow wider and shal- lower as they advance, until the western channels are lost in the hard plain, and the eastern channels in a succession of marshes. But they reappear once more below the parallel of Hala and Kipra, and continue their courses as already described above.*

- See Map No. IX.

In Upper Sindh the only places of ancient note are Alor, Rori-Bhakar, and Mahorta, near Larkâna. Several other places are mentioned in the campaigns of Alexander, Chach, Muhammad bin Kâsim, and Husen Shah Arghun; but as the distances are rarely given, it is difficult to identify the positions where names are so constantly changed. In the campaign of Alexander we have the names of the Massana, the Sogdi, the Musikani, and the Præsti, all of which must certainly be looked for in Upper Sindh, and which I will now attempt to identify.

Massana and Sodra, or Sogdi.

On leaving the confluence of the Panjâb rivers, Alexander sailed down the Indus to the realm of the Sogdi, Zoydot, where, according to Arrian,* "he built another city." Diodorus† describes the same people, but under a different name:-"Continuing his descent of the river, he received the submission of the Sodra and the Massana, nations on opposite banks of the stream, and founded another Alexandria, in which he placed 10,000 inhabitants." The same people are described by Curtius, although he does not mention their names :—“On the fourth day he came to other nations, where he built a town called Alexandria." From these accounts it is evident that the Sogdi of Arrian and the Sodra of Diodorus are the same people, although the former have been identified with the Sodha Rajputs by Tod and M'Murdo, the latter with the servile Sudras by Mr. Vaux. The Sodhas, who are a branch of the Pramâras, now occupy the south-

- Anabasis,' vi. 15.

† Hist. Univers. xvii. 56.

+ Vita Alex., ix. 8. eastern district of Sindh, about Umarkot, but according to M'Murdo,* who is generally a most trustworthy guide, there is good reason to believe that they once held large possessions on the banks of the Indus, to the northward of Alor. In adopting this extension of the territory formerly held by the Sodha Rajputs, I am partly influenced by the statement of Abul Fazl, that the country from Bhakar to Umarkot was peopled by the Sodas and Jharejas in the time of Akbar,+ and partly by the belief that the Massana of Diodorus are the Musarnei of Ptolemy, whose name still exists in the district of Muzarka, to the west of the Indus below Mithankot. Ptolemy also gives a town called Musarna, which he places on a small affluent of the Indus, to the north of the Askana rivulet. The Musarna affluent may therefore be the rivulet of Kâhan, which flows past Pulaji and Shahpur, towards Khângarha or Jacobabad, and Musarna may be the town of Shahpur, which was a place of some conse- quence before the rise of Shikarpur. "The neigh- bouring country, now nearly desolate, has traces of cultivation to a considerable extent." The Sogdi, or Sodra, I would identify with the people of Seorui, which was captured by Husen Shah Arghun on his way from Bhakar to Multân.§ In his time, A.D. 1525, it is described as "the strongest fort in that country." It was, however, deserted by the garrison, and the conqueror ordered its walls to be razed to the ground. Its actual position is unknown, but it was

- Journ. Royal Asiat. Soc. i. 33.

Thornton, Gazetteer,' in voce.

§ Erskine's Hist. of India, i. 388. Bengal, 1841, 275.

† Ayin Akbari,' ii. 117. Postans, Journ. Asiat. Soc. probably close to Fâzilpur, halfway between Sabzal- kot and Chota Ahmedpur, where Masson* heard that there was formerly a considerable town, and that "the wells belonging to it, 360 in number, were still to be seen in the jangals." Now in this very position, that is about 8 miles to the north-east of Sabzalkot, the old maps insert a village named Sirwahi, which may pos- sibly represent the Seorai of Sindhian history. It is 96 miles in a direct line below Uchh, and 85 miles above Alor, or very nearly midway between them. By water the distance from Uchh would be at least one-third greater, or not less than 120 miles, which would agree with the statement of Curtius that Alex- ander reached the place on the fourth day. It is ad- mitted that these identifications are not altogether satisfactory; but they are perhaps as precise as can now be made, when we consider the numerous fluctua- tions of the Indus, and the repeated changes of the names of places on its banks. One fact, preserved by Arrian, is strongly in favour of the identification of the old site near Fâzilpur with the town of the Sogdi, namely, that from this point Alexander dispatched Kraterust with the main body of the army, and all the elephants, through the confines of the Arachoti and Drangi. Now the most frequented Ghât for the crossing of the Indus towards the west, viâ the Gan- dâva and Bolân Pass, lies between Fâzilpur on the left bank, and Kasmor on the right bank. And as the ghâts, or points of passage of the rivers, always determine the roads, I infer that Kraterus must have begun his long march towards Arachosia and Dran- giana from this place, which is the most northern

- Travels,' i. 382.

† Anabasis,' vi. 15. position on the Indus for the departure of a large army to the westward. It seems probable, however, that Kraterus was detained for some time by the revolt of Musikanus, as his departure is again men- tioned by Arrian,* after Alexander's capture of the Brahman city near Sindomana. Between Multân and Alor the native historians, as well as the early Arab geographers, place a strong fort named Bhatia, which, from its position, has a good claim to be identified with the city which Alex- ander built amongst the Sogdi, as it is not likely that there were many advantageous sites in this level tract of country. Unfortunately, the name is variously written by the different authorities. Thus, Postans gives Paya, Bahiya, and Páhiya; Sir Henry Elliot gives Púbiya, Bátia, and Bhatiya, while Price gives Bahátia. It seems probable that it is the same place as Talhati, where Jâm Janar crossed the Indus; and perhaps also the same as Mátila, or Mahátila,§ which was one of the six great forts of Sindh in the seventh century.

Bhatia is described by Ferishta as a very strong place, defended by a lofty wall and a deep broad ditch. It was taken by assault in A.H. 393, or A.D. 1003, by Mahmud of Ghazni, after an obstinate de- fence, in which the Raja, named Bajjar, or Bijé Rai, was killed. Amongst the plunder Mahmud obtained no less than 280 elephants, a most substantial proof of the wealth and power of the Hindu prince.

Anabasis,' vi. 17. † Dowson's edition of Sir H. Elliot, i. 138. Journ. Asiat. Soc. Bengal, 1845, p. 171. § Ibid., 1845, p. 79. ||Briggs's Ferishta,' i. 39; and Tabakât.i. Akbari, in Sir Henry Elliot, p. 186. . Musikani Alor.

From the territory of the Sogdi or Sodra, Alexander continued his voyage down the Indus to the capital of a king named Musikanus, according to Strabo, Dio- dorus, and Arrian,* or of a people named Musicani, according to Curtius.† From Arrian we learn that this kingdom had been described to Alexander as "the richest and most populous throughout all India;" and from Strabo we get the account of Onesikritus that "the country produced everything in abundance;" which shows that the Greeks them- selves must have been struck with its fertility. Now these statements can apply only to the rich and powerful kingdom of Upper Sindh, of which Alor is known to have been the capital for many ages. Where distances are not given, and names disagree, it is difficult to determine the position of any place from a general description, unless there are some pe- culiarities of site or construction, or other properties which may serve to fix its identity. In the present instance we have nothing to guide us but the general description that the kingdom of Musikanus was “the richest and most populous throughout all India." But as the native histories and traditions of Sindh agree in stating that Alor was the ancient metropolis of the country, it seems almost certain that it must be the capital of Musikanus, otherwise this famous city would be altogether unnoticed by Alexander's historians, which is highly improbable, if not quite impos-

- Strabo, Geogr., xv. i. 22-34 and 54. Diodorus, xvii. 10. Arrian,

"Anabasis,' vi. 15. † Vita Alex., ix. 8.

S Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/304 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/305 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/306 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/307 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/308 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/309 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/310 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/311 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/312 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/313 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/314 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/315 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/316 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/317 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/318 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/319 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/320 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/321 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/322 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/323 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/324 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/325 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/326 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/327 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/328 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/329 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/330 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/331 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/332 these names, which is thus mentioned in conjunction with Manhâbari might possibly be intended for Nirun, and the other two for Nirunkot, as the alterations in the original Arabic characters required for these two readings are very slight. But there was cer- tainly a place of somewhat similar name in Mekrân, as Bilâduri records that Kizbun in Mekrân submitted to Muhammad Kâsim on his march against Debâl. Comparing this name with Ibn Haukal's Kannazbur,* and Edrisi's Firabuz, I think it probable that they may be intended for Panjgur, as suggested by M. Reinaud. The 14 days' journey would agree very well with the position of this place.

Jarak.

The little town of Jarak is situated on an eminence overhanging the western bank of the Indus, about midway between Haidarâbâd and Thatha. Jarak is the present boundary between Vichalo, or Middle Sindh, and Lár, or Lower Sindh, which latter I have been obliged to extend to Haidarâbâd, so as to include the Patala of the Greeks and the Pitasilu of the Chinese pilgrim, within the limits of the ancient Delta. This is perhaps the same place as Khor, or Alkhor, a small but populous town, which Edrisi places between Manhâbari and Firabuz, that is, be- tween Thatha and Nirunkot. Three miles below Jarak there is another low hill covered with ruins,

- Prof. Dowson's edition of Sir Henry Elliot's Hist. of India, i. 40.

Ibn Haukal: Kannazbur. At page 29 he gives Istakhri's name as Kannazbûn, which Mordtmann reads Firiun. The most probable ex- planation of these differences is some confusion in the Arabic characters

between the name of Nirun and that of the capital of Mekrân. Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/334 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/335 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/336 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/337 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/338 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/339 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/340 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/341 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/342 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/343 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/344 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/345 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/346 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/347 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/348 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/349 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/350 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/351 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/352 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/353 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/354 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/355 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/356 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/357 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/358 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/359 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/360 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/361 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/362 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/363 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/364 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/365 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/366 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/367 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/368 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/369 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/370 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/371 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/372 X.

A. Cunningham delt.

by Mr. Bowring. The circuit stated by the Chinese pilgrim could not have been more than 35 or 10 miles, at 7 or 8 miles to the yojana, but the circle mentioned by Abul Fazl could not be less than 53 miles, at the usual valuation of the Padshahi kos at 13 miles, and might, at Sir H. Elliot's valuation of Akbar's kos at more than 2 miles, be extended to upwards of 100 miles. It is possible, indeed, to make these different statements agree very closely by changing the pilgrim's number to 400 li, or 10 yojanas, which are equivalent. to 40 kos, or 80 miles, and by estimating Abul Fazl's 40 kos at the usual Indian rate of about 2 miles each. I am myself quite satisfied of the necessity for making this correction in the pilgrim's number, as the narrow extent of his circle would not only shut out the equally famous shrines at Prithudaka, or Pehoa on the Saraswati, and at the Kausiki-Sangam, or junction of the Kausiki and Drishadwati rivers, but would actually exclude the Drishadwati itself, which in the l'amana Purána is specially mentioned as being within the limits of the holy land,-

Dirgh-Kshetre Kurukshetre dirgha Satranta yire Nudyâstire Drishadvatyâh punyayah Suchirodhasah. "They were making the great sacrifice of Satrantu in the wide region of Kurukshetra on the banks of the Drishadwati, esteemed holy on account of its virtues." This river is also specially mentioned in the Fana Parva of the Mahabharata as being the southern boundary of the holy land.*

Dakshinena Sarasvatyâ Drishadvatyuttarena-cha Ye vasanti Kurukshetre te vasanti trivishtape.

"South from Saraswati, and north from Drishadwali,

- Chap. 83, v. 4. Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/382 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/383 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/384 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/385 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/386 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/387 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/388 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/389 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/390 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/391 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/392 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/393 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/394 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/395 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/396 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/397 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/398 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/399 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/400 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/401 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/402

punishment of being born again in an inferior state, which was due to their crimes. I should prefer read- ing Subhadra, which has the same meaning as Ma- hâbhadrâ, as Ktesias mentions that the great Indian river was named ὕπαρχος, which he translates by φέρων πάντα τὰ ἀγαθὰ.[23] Pliny quoting Ktesias calls the river Hypobarus, which he renders by "omnia in se ferre bona."[24] A nearly similar word, Oibares, is rendered by Nicolas of Damascus as ȧyabáyyeλos. I infer, there- fore, that the original name obtained by Ktesias was most probably Subhadrâ.

5. BRAHMAPURA.

On leaving Madâwar, Hwen Thsang travelled north- ward for 300 li, or 50 miles, to Po-lo-ki-mo-pu-lo, which M. Julien correctly renders as Brahmapura. Another reading gives Po-lo-hi-mo-lo,[25] in which the syllable pu is omitted, perhaps by mistake. The northern bearing is certainly erroneous, as it would have carried the pilgrim across the Ganges and back again into Srughna. We must therefore read north-east, in which direction lie the districts of Garhwâl and Kumaon that once formed the famous kingdom of the Katyuri dynasty. That this is the country intended by the pilgrim is proved by the fact that it produced copper, which must refer to the well-known copper mines of Dhanpur and Pokhri in Garhwal, which have been worked from a very early date. Now the ancient capital of the Katyuri Rajas was at Lakhanpur or Fairát-pattan on the Râmgangâ river, about 80 miles in a direct line from Madawar. If we might take the measurement

2 ▲ 2 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/404 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/405 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/406 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/407 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/408 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/409 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/410 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/411 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/412 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/413 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/414 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/415 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/416 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/417 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/418 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/419 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/420 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/421 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/422 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/423 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/424 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/425 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/426 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/427 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/428 before the use of cannon the height alone must have made Kanoj a strong and important position. The people point out the sites of two gates, the first to the north, near the shrine of Haji Harmáyan, and the second to the south-east, close to the Kshem Kali Búrj. But as both of these gates lead to the river, it is cer- tain that there must have been a third gate on the land side towards the south-west, and the most pro- bable position seems to be immediately under the walls of the Rang Mahal, and close to the temple of Ajay Pál.

According to tradition, the ancient city contained 84 wards or Mahalas, of which 25 are still existing within the limits of the present town. If we take the area of these 25 wards at three-quarters of a square mile, the 84 wards of the ancient city would have covered just 2½ square miles. Now, this is the very size that is assigned to the old city by Hwen Thsang, who makes its length 20 li, or 3 miles, and its breadth 4 or 5 li, or just three-quarters of a mile, which multi- plied together give just 2 square miles. Almost the same limits may be determined from the sites of the existing ruins, which are also the chief find-spots of the old coins with which Kanoj abounds. According to the dealers, the old coins are found at Bála Pir and Rang Mahal, inside the fort; at Makhdum-Juhaniya, to the south-east of the fort; or Makarandnagar on the high-road; and intermediately at the small villages of Singh Bhawani and Kútlúpur. The only other produc- tive site is said to be Rájgir, an ancient mound covered with brick ruins on the bank of the Chota Gangú, three miles to the south-east of Kanoj. Taking all these

evidences into consideration, it appears to me almost Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/430 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/431 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/432 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/433 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/434 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/435 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/436 XI.

A. Cunningham delt.

of the name of Kosdmhi mandala, or " Kingdom of Kosambi," in an inscription over the gateway of the fort of Khara^ seem to confirm the general belief, although the south-west bearing from Prayaga, or Allahabad, as recorded by Hwen Thsang, points un- mistakably to the line of the Jumna. In January, 1861, Mr. Bayley informed me that he believed the ancient Kosambi would be found in the old village of Kosam, on the Jumna, about 30 miles above Allaha- bad. In the following month I met Babu Siva Prasad, of the educational department, who takes a deep and intelligent interest in all archseological subjects, and from him I learned that Kosam is still known as Ko- sdmbi-iiaffar, that it is even now a great resort of the Jains, and that only one century ago it was a large and flourishing town. This information was quite sufficient to satisfy me that Kosam was the actual site of the once famous Kosambi. Still, however, there was no direct evidence to show that the city was situated on the Jumna ; but this missing link in the chain of evidence I shortly afterwards found in the curious legend of Bakkula, which is related at length by Hardy.[26] The infant Bakkula was born at Ivosambi, and while his mother was bathing in the Jumna, he accidentally fell into the river, and being swallowed by a fish, was carried to Benares. There the fish was caught and sold to the wife of a nobleman, who on opening it found the young child still alive inside, and at once adopted it as her own. The true mother hearing of this wonderful escape of the infant, proceeded to Be- nares, and demanded the return of the child, which was of course refused. The matter was then referred Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/445 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/446 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/447 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/448 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/449 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/450 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/451 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/452 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/453 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/454 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/455 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/456 houses of the neighbouring city of Faizabad. This Muhammadan city, which is two miles and a half in length by one mile in breadth, is built chiefly of ma- terials extracted from the ruins of Ajudhya. The two cities together occupy an area of nearly six square miles, or just about one-half of the probable size of the ancient capital of Kama. In Faizabad the only building of any consequence is the stuccoed brick tomb of the old Bhao Begam, whose story was dragged be- fore the public during the famous trial of Warren Hastings. Faizabad was the capital of the first Na- wabs of Oudh, but it was deserted by Asaf-ud-daolah in A.D. 1775.

In the seventh century the city of Visdkha was only 16 li, or 2|- miles, in circuit, or not more than one-half of its present size, although it probably contained a greater population, as not above one-third or perhaps less of the modern town is inhabited. Hwen Thsang assigns to the district a circuit of 4000 li, or 667 miles, which must be very much exaggerated. But, as I have already observed, the estimated dimensions of some of the districts in this part of the pilgrim's route are so great that it is quite impossible that all of them can be correct. I would therefore, in the present instance, read 400 li, or 67 miles, and restrict the territory of Visdkha to the small tract lying around Ajudhya, between the Ghagra and Gomati rivers.

18. SEAVASTI.

The ancient territory of Ayodliya, or Oudh, was divided by the Sarju or Ghagra river into two great provinces ; that to the north being called TJltara Kosala, and that to the south Banaodha. Each was again subdivided into two districts. In Banaodha these are called Pachham-rdt and Purab-rdt, or the western and eastern districts ; and in Uttara Kosala they are Gauda (vulgarly Gondu) to the south of the Eapti, and Kosala to the north of the Eapti, or Rdwati, as it is univer- sally called in Oudh. Some of these names are found in the Puranas. Thus, in the Yayu Purana, Lava the son of Eama is said to have reigned in Uttara Eosala; but in the Matsya Linga and Kurma Puranas, Srdvasti is stated to be in Gauda. These apparent discrepancies are satisfactorily explaiued when we learn that Gauda is only a subdivision of Uttara Kosala, and that the ruins of Sravasti have actually been discovered in the district of Gauda, which is the Gonda of the maps. The extent of Gauda is proved by the old name of Balrampur on the Eapti, which was formerly Ra7n- garli-Gauda. I presume, therefore, that both the Gauda Brahnans and the Gauda Tac/as must originally have belonged to this district, and not to the medi- asval city of Gauda in Bengal. Brahmans of this name are still numerous iu Ajudhya and Jahangirabad on the right bank of the Ghagra river, in Gonda, Pa- khapur, and Jaisni of the Gonda or Gauda district on the left bank, and in many parts of the neighbouring province of Gorakhpur. Ajiidltya, therefore, was the capital of Banaodha, or Oudh to the south of the Gha- gra, while Srdvasti was the capital of Uttara Kosala, or Oudh to the north of the Ghagra.

The position of the famous city of Srdvasti, one of the most celebrated places in the annals of Buddhism, has long puzzled our best scholars. This was owing partly to the contradictory statements of the" Chinese pilgrims themselves, and partly to the want of a good Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/459 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/460 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/461 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/462 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/463 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/464 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/465 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/466 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/467 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/468 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/469 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/470 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/471 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/472 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/473 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/474 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/475 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/476 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/477 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/478 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/479 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/480 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/481 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/482 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/483 the south of Kahaon, and 7 miles below the confluence of the two rivers. From Kasia to the Mahili Ghat the route would have passed through the ancient towns of Khuhkundo and KaJiaon^ both of which still possess many remains of antiquity. But the former is only 28 miles from Kasia, while the latter is 35 miles. Both are undoubtedly Brahmanical ; but while the ruins at Khukhundo are nearly all of middle age, those at Kahaon are at least as old as the time of Skanda Gupta, who lived several centuries before the time of Hwen Thsang. I am inclined, therefore, to prefer the claim of Kahaon as the representative of Hwen Thsang' s ancient city, partly on account of its undoubted antiquity, and partly because its distance from Kasia agrees better with the pilgrim's estimate than that of the larger town of Khukhundo.[27]

Pawa, or Padraona.

In the Ceylonese chronicles the town of Padwa is mentioned as the last halting-place of Buddha before reaching Kusinagara, where he died. After his death it is again mentioned in the account of Kasyapa's journey to Kusinagara to attend at the cremation of Buddha's corpse. Padaa was also famous as one of the eight cities which obtained a share of the relics of Buddha. In the Ceylonese chronicles it is noted as being only 12 miles from Kusinagara,[28] towards the Gandak river. Now 12 miles to the north-north-east of Kasia there is a considerable village named Pada- raona, or Padara-vana, with a large mound covered with broken bricks, in which several statues of Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/485 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/486 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/487 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/488 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/489 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/490 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/491 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/492 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/493 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/494 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/495 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/496 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/497 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/498 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/499 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/500 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/501 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/502

XII.

A. Cunningham delt.

of the second and third centuries.[29] Ptolemy has l[arundai as the name of a people to the north of the Gauges ; hut to the south of the river he places the jIuniMi, who may be the Mundas of Chutia ISTagpur, as their language and country are called Mmdala. This is only a suggestion ; but from the position of the Mandali they wovX(. seem to be the same people as tlie Monedes of Pliny, who with the 8uari occupied the inland country to the south of the Palibothri.[30] As this is the exact position of the country of the Mdndas and Suars, I think it quite certain that they must be the same race as the Monedes and Suari of Pliny.

In another passage Pliny mentions the Mandei and Malli as occupying the country between the CalingcB and the Ganges,[31] Amongst the Malli there was a mountain named Mallus, which would seem to be the same as the famous Mount Maleus of the Monedes and Suari. I think it highly probable that both names may be intended for the celebrated Mount Mandar, to the south of Bhdffalpur, which is fabled to have been u.sed by the gods and demons at the churning of the ocean. The Mandei I would identify with the inha- bitants of the Mahunadi river, which is the Manada of Ptolemy. The Malli or Malei would therefore be the same people as Ptolemy's Mandalce, who occupied the right bank of the Ganges to the south of Pali- bothra. Or they may be the people of the Bdjmahal

hills who are called Maler, which would appear to be Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/561 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/562 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/563 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/564 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/565 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/566 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/567 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/568 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/569 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/570 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/571 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/572 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/573 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/574 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/575 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/576 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/577 Page:The Ancient Geography of India.djvu/578 XIII.

A. Cunningham delt.

Tables as placing the Andhras "on the banks of the Ganges," but the extremely elongated form of the Pentingerian Map has squeezed many of the peoples and nations far out of their true places. A much safer conclusion may be inferred from a comparison of the neighbouring names. Thus the Andra-Indi are placed near Damirice, which I would identify with Ptolemy's Limyrike by simply changing the initial 4 to 4, as the original authorities used for the construction of the Tables must have been Greck. But the people of Limyrike occupied the south-west coast of the penin- sula, consequently their neighbours the Andræ-Indi must be the well-known Andhras of Telingana, and not the mythical Andhras of the Ganges, who are mentioned only in the Puránas. Pliny's knowledge of the Andaræ must have been derived either from the Alexandrian merchants of his own times, or from the writings of Megasthenes and Dionysius, the ambassa- dors of Seleukus Nikator and Ptolemy Philadelphus to the court of Palibothra. But whether the Andaræ were contemporary with Pliny or not, it is certain that they did not rule over Magadha at the period to which he alludes, as immediately afterwards he mentions the Prasii of Palibothra as the most powerful nation in India, who possessed 600,000 infantry, 30,000 horse, and 9000 elephants, or more than six times the strength of the Andaræ-Indi.

The Chinese pilgrim notices that though the lan- guage of the people of Andhra was very different from that of Central India, yet the forms of the written characters were for the most part the same. This statement is specially interesting, as it shows that

- Vishnu Purana,' Hall's edition, iv. 203, note.

2 M the old Nâgari alphabet introduced from Northern India was still in use, and that the peculiar twisted forms of the Telugu characters, which are found in inscriptions of the tenth century, had not yet been adopted in the south.

4. DONAKAKOTTA.