The American Boy's Handy Book/Chapter 20

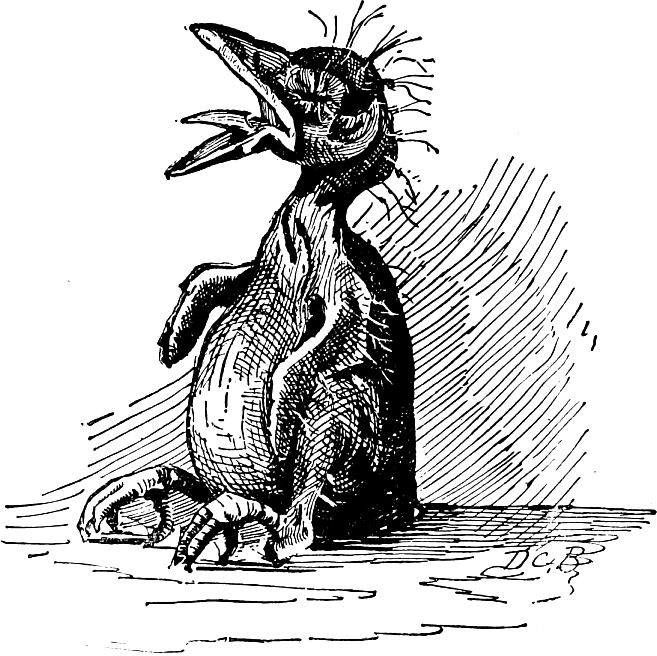

A fuzzy topknot surmounting a head too heavy for the slender neck to hold upright; large, protruding eyes protected by lids that are tightly gummed together; a bluish black skin, with no feathers to hide the wrinkles; a large paunch like an alderman. Such is the appearance of a very young crow; and after a glance at the accompanying sketch, drawn from nature, the reader will no doubt agree with the writer in calling it the worst looking "baby in the woods," and if mischief be a sign of badness, then "Jim Crow" does not belie his looks. He is especially comical when his great blood-red mouth is expanded to its utmost dimension in expectancy as he awaits a morsel of food.

Of all our native birds the crow is probably the hardiest, and the least trouble to bring up by hand. Almost any kind of soft food, bread and milk, corn meal mush, grub worms, raw lean meat, or raw liver is devoured with relish by the black baby; any of the foods described in the preceding chapter may be fed to the crow. As soon as he is able to walk "Jim" will begin to learn to eat without help. The feathers will by this time have grown, covering the body with a suit of glossy black, which gives the bird a very genteel and respectable appearance. The crow ought never to be confined in a cage, but allowed to wander around at will.

The first crow that came into the author's possession had scarcely escaped from its egg-shell prison before it was taken from the cradle of rough sticks that the parent birds had built near the top of a pine tree.

The bird was christened Billy, and from morn until night the neighbors could hear him as he loudly clamored for food. Before school-time in the morning an egg was broken and the contents of the shell dropped into William's great red mouth; with a gobbling noise the egg would be swallowed; then as if satisfied for the present he would settle down for a nap. During the noonday recess, Billy, with his red mouth wide open, was always loudly calling for his noontime meal, which consisted of the same material as his breakfast and supper. Three eggs a day kept the little black rascal fat and healthy, and it was not long before the naked little body was covered with a coating of glossy black feathers, and Billy, abandoning the old basket which had served him for a nest, now awaited his master's return from school, perched upon the iron railing fence of the front yard. From eggs to fresh liver was an easy step, and one that the bird gladly took. Corn he never ate unless it was in the form of "Johnny-cake" or mush; stale meat was his detestation; in fact, a cleaner or more dainty bird in regard to his food was never reared. Billy was not long in making a name and reputation for himself; a more affectionate and mischievous imp never wore a coat of black or buried silver thimbles in a flower bed. Although his pranks were often very annoying, they were always amusing, and no one ever thought the less of the bird for stealing all the fish from the miniature pond, nor did his master's anger, though great, cause him to administer severe punishment to the black culprit when he discovered the fish all neatly stowed away under the shingles of the rabbit house. When the young rabbits were discovered nicely pressed between the leaves of some books of travel just purchased, the gentleman to whom the books belonged declared war. He went to the lawn to search for Billy, and the bird flew to him, and, alighting upon his shoulder in the most fearless and confident manner, commenced a long explanation of his misdeeds in the crow language. What he said was unintelligible; but the gentleman's anger was not only mollified but changed to mirth, for he came back to the house laughing heartily. Billy, still perching upon his shoulders, seemingly enjoyed the situation.

Since the writer's first experiment he has brought up several other crows successfully upon a diet of fresh meat, bread and milk, and boiled potatoes mixed with eggs.

Naturally possessed of a wild, fierce nature, loving the open air and the wide, blue sky, the hawk is a born freebooter; but wild and fierce as he is, he may nevertheless be perfectly tamed if taken from the nest when quite young.

After you have obtained a young hawk, make it a rule to always feed it yourself and never allow any one else to do so. Give a peculiar whistle (in the same manner) each time you feed it, and the bird will learn to know the signal and come at the call. Keep the hawk in your company as much as possible, and when you can, set its perch where it will see the people around the house, and become accustomed to their presence; by this means the bird may be taught not to fear man, and it will soon become as harmless as any small cage-bird.

Feed young hawks upon fresh lean meat of any kind. When they grow older they develop a fondness for rats, mice, and small birds. Do not trouble yourself about their drinking-water, as they do not need it.

A tame hawk is very useful in keeping the chickens out of the garden. Whenever the writer has placed the perch with his pet hawk upon it in the garden, not a chicken has dared to enter the enclosure; they all seem to know their enemy by instinct, and give it a wide berth.

The hawk himself seems to know when he is doing guard duty, and will sit as motionless as a statue, his head sunk down upon his shoulders, but the keen, bright eyes survey the whole field, and not an object moves that they do not see.

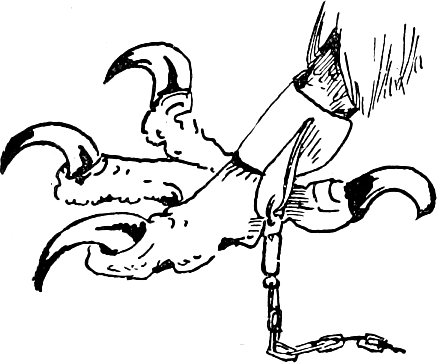

If you want to trap other birds a tame hawk is a very valuable assistant. At any convenient spot set your bird traps, near by fasten the hawk, and retire a little distance; it will not be many minutes before the small birds will discover their dreaded enemy, and from bush and tree the spunky little feathered warriors will come to give battle. In a few moments the ground and air around the hawk will be filled with robins, catbirds, blackbirds, sparrows, yellowbirds, thrushes, wrens, and even the tiny humming-bird, making up in grit what he lacks in size, will join the other birds in their war against a common foe. In the confusion and bustle that ensues some of the small birds are sure to enter a trap or become entangled in a snare, and must be removed before they injure themselves in struggling to regain their freedom. As soon as you retire a little distance the small birds will again commence their war upon the pet hawk, who is thoroughly competent to take care of himself, so you can devote your whole attention to your traps. As a pet the hawk is a pretty bird, and always charms spectators by his bold, military bearing and his bright, clear eyes.

the author has found inclined to be more wild and untamable than hawks and not so interesting. Even the little screech-owls are vicious and treacherous, snapping their small bills in a savage way whenever they are approached. A friend sends word that he has been more successful, and has even succeeded in taming the great Virginia horned owl, which was allowed to fly around with perfect freedom. "Bubo" would fly all over the village but return at meal times; he would come at a call and knew his master, obeying him even to the extent of letting go his hold of a pet bobolink when commanded to do so. The bobolink, though a little bruised, was otherwise unhurt, and soon recovered from the effects of being caught in the dreaded talons of "Bubo."

Any of the guillemot tribe will do well if kept in an enclosure where there is room for them to run about. The author has seen numbers of tame sea birds, although he never attempted to rear one himself, and would advise the reader not to try unless he has plenty of room. Sea birds are strange creatures, and their characteristics are so well portrayed by a writer for The London Field that part of the amusing article is here given in the writer's own words:

"I have been forced to banish a couple of herring gulls, as they persist in tearing up the grass by the roots. Some few years back I had a third of the same species, named 'Sims Reeves' (all the birds are named, so that I can give directions for special treatment to any particular individual during my absence); but he asserted his authority over the other two, 'Moody' and 'Sankey,' in such an overbearing manner—driving them round and round the pond, the two poor wretches meekly trotting in front of him, while he every now and then gave vent to the most melancholy and piercing screams—that, as I found they would not live peaceably together, Sims Reeves was allowed to go with his wing unclipped, and in due course took his departure. No sooner had he gone than Moody at once became 'boss,' and the last state of poor Sankey was no better than the first. At times they were quiet and contented enough; resting side by side on the grass, they appeared to be the best of friends. Without the slightest warning, however, Moody would arise, and when he had cleared his throat by a preliminary 'caterwaul,' the submissive Sankey, having learned by experience that it would not do to be caught, would be up and off. Then, with his head drawn back between his shoulders and his feathers slightly puffed out, Moody would follow in his wake. For an hour or so this mournful procession, round and round the pond, would continue. At last Moody would stop, Sankey also pulling up at the distance of a yard or two. Moody leading, they would then commence a duet à la tomcat, when, suddenly dropping on their breasts on the ground, they would turn rapidly round several times, and at last attack the grass in the most excited manner, tearing it up by the roots and scattering the fragments in every direction. This proceeding is accompanied by the most melancholy cries and screams, and when it is stated that the voice of Grimalkin in his happiest, or rather his unhappiest moods, is almost sweet and pleasing to the ear compared with the discordant wailing of these infatuated birds, one may judge of the nature of their performance. Whether these antics are intended for courtship or defiance I am perfectly ignorant, but I have observed pewits acting in much the same manner. At first I imagined the bird was forming its nest (I was in a punt at about ten yards' distance), but on examining the spot on the following day I found no marks, and then came to the conclusion that the bird was either showing himself off for the admiration of the female, who was close by, or else bidding defiance to another male, which I could plainly see indulging in the same performance at a short distance. I have not the slightest doubt that gulls, and every species of sea bird, might, with proper attention and food, be so thoroughly reconciled to con finement that they would nest and rear their young."

In a small town situated in the interior of Georgia there lives a queer sort of sporting character, who has, or did have a few years ago, the strangest collection of fowls in his chicken-yard that it has ever been my fortune to see. I was strolling along a side street in the town when my attention was attracted by the sight of a large black bear chained to the door-post of a small frame tavern. While watching the huge beast, I was accosted by the proprietor, and invited into the barn-yard to see his "chickens," which he was about to feed. The invitation was accepted. At the first call of chick! chick! there came flying and running a curious assortment of fowls, tumbling over each other in their greedy haste. There were ducks, geese, and chickens like those to be seen in any farmyard, but mingled with these were wild geese, mud hens, partridges, and beautiful little wood ducks; the latter seemed tamer than the domestic species. Towering above all the other fowls, flapping his wings, and making a loud metallic noise, was a great long-legged, red-headed crane. I afterward learned that the wild geese and ducks had their wings clipped, for, although they may be perfectly tame, these birds are very liable to fly away in the autumn when they see or hear their wild "cousins" and their "aunts" flying overhead. I give this little experience to show the boys that any bird may be domesticated if its habits and wants are understood; of course, it is always best to take young birds for the purpose.