Stokes on Memory/Organization

The organization and quality of the brain have undoubtedly a great influence upon natural Memory, sometimes rendering it either good or bad for names, dates, words, places, persons, events, etc., etc.; but whenever defects exist, they may be either greatly remedied, or entirely removed, by the use of methods which enable the fully developed faculties to perform the duties of what appear to be those portions of the brain which are defective, presuming that there is enough intelligence to enable the pupil to read; we may thus regard the acquirement of what is generally called "a good Memory," to be not simply a possibility, but a thing to be easily obtained; thus Mnemonics renders Memory—ordinary powers of Memory—almost independent of organization.

As we have already seen, sometimes one kind of Memory may be substituted for another, or reasoning, wit, or imagination may lend their friendly aid. To speak in popular phraseology, there are four kinds of Memory—tongue, ear, eye, and brain Memory. The method of learning generally employed in schools and elsewhere, is repeating, depending almost entirely upon the tongue and the ear for accuracy; the eye (or the mind's eye) and the reasoning faculties having little or nothing to do with it. The result, in many cases, must be forgetfulness, which may be avoided by Mnemonic visual or reflective memory.

MENTAL PICTURING.

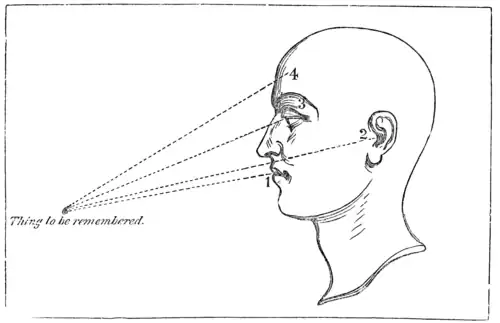

Perfection of association is that which secures the united and harmonious action of the greatest number of powers which can be brought into use for the object desired. We may fail to remember, from want of articulating, or from inattention to our articulation, but more frequently forgetfulness arises from not picturing—imperfectly picturing, or incorrectly picturing. Intellectual association is mainly dependent upon the mind's eye. Impressions may be made variously, but sometimes thus:—The tongue gives an utterance which is conveyed to the ear; the ear-received utterance produces a mental picture, which is received by the eye, and the impression on the eye awakens reflection—a mental comment, or remark, or action of the intellect. It often strangely happens that the mental remark which we make upon a thing is better remembered than the thing itself. Hence the importance of reflection, or intellectual action, as an aid to Memory. (See page 79.)

It is not imperative that a remark should possess the characteristic of wit, yet a witty remark is often well remembered, thus:—A pupil could not tell which arm Nelson lost; but upon being informed, said,—"I shall not forget that now; I see it was not the one

Diagram illustrative of the simultaneous operation of lingual, aural, visual, and intellectual association

Few things have been more parroted than the words, "Do not parrot." It is undoubtedly highly objectionable to repeat, invariably by rote, without understanding the meaning of that which we utter; but, therefore, to repudiate this process altogether, is ridiculous, because the parroting and reflective powers may be combined in the same individual with immense advantage; he may parrot first, and afterwards reflect. In fact, if we can only learn that about which we can give the philosophical why and wherefore, we must often forego valuable fresh acquisitions.

It would be well to revive, in a measure, that which is unfortunately almost a thing of the past—the practice of "learning by heart." A few years ago, it was customary to cram children with words, regardless of their meaning, which was decidedly objectionable, and was very properly condemned by discerning educational reformers; but a sort of reaction has been the result, and, at the present day, there are many who almost attempt to convey meaning without words! To possess the power of learning verbatim, with rapidity and ease, is unquestionably, in many instances, an immense advantage; but in too many cases, it is repudiated by instructors and dreaded by pupils, whereas it ought to be encouraged and enjoyed!

If you have a child who is quick at "parroting," but dull of comprehension, do not try to check its learning by rote, but endeavour to awaken intelligence, by carefully and patiently questioning it upon the meaning of that which it has learned; particularly avoiding putting difficult questions at the onset. Interrogation, with such a child, is preferable to explanation; but of course its replies will frequently require correction.

The best plan of insuring remembrance appears to be to allow the Memory to do its own work when it can, and when it cannot, to bring to its assistance whichever other faculty may be most advantageous, not always taxing one or two particular powers, but securing an agreeable and advantageous division of labour.

In order to strengthen the Memory, then, it is desirable to picture clearly as much as possible. The expert Mnemonist is best qualified to do this, but it may generally be done to a much greater extent than is supposed, by the ordinary thinker.

ILLUSTRATIVE MENTAL PICTORIAL EXERCISE.

I want you to think at once of a horse—

Now tell me, are you able

To say if it seemed to be in a field,

On a road, or in a stable?

Can you describe its kind of breed?

Did it seem a steady pacer?

Was it cart-horse, dray-horse, hunter, or hack,

A charger, wild horse, or racer?

And now can you say what colour it was

And which way it was going?

If you pictured well, you can all this tell,

If not, there will be no knowing.

The perfection, defects, beauty, comicality, or peculiarities of a piece are rendered more apparent by Picturing, thus:—

Upon a dark and rainy night,

Through a dense wood his way was wending,

An aged man in doleful plight,

Upon his stick his form was bending.

His brow was knit, his eyes cast down,

In voice discordant he was speaking,

He muttered as he gave a frown—

"Confound it, how my boots are leaking!"

"ANTI-NONSENSICAL NURSERY RHYME."

To be taught and explained by the parent.

Try to learn, my little dear,

Not by dinning on your ear;

But by thought and mental sight,

Which give pleasure, speed, and might!

Many dispute the desirability of attempting to Picture, believing it to be very dangerous—as likely to retard as it is to facilitate, and to mislead as much as to guide. This objection is well grounded if brought to bear simply upon unskilful Picturing, but with an experienced Mnemonist at his elbow, it is not likely that the novice will be allowed to go far wrong.

Many of the ablest men who have written upon the mind have appreciated the power and superiority of visual impressions; some of the best metaphysicians, universally recognised authorities, have expressed opinions, or rather have directed attention to facts which place the value of picture-forming Mnemonics beyond all doubt. Dr. Watts, when speaking of Memory and Imagination, in his supplement to the "Art of Logic," says—

"Sounds which address the ear are lost, and die

In one short hour, but that which strikes the eye

Lives long upon the mind; the faithful sight

Engraves the image with a beam of light."

Skilfully used Pictorial Mnemonics is a species of mental photography.

THE REMEMBRANCE OF NAMES, ETC.

Again, in reference to names. It really cannot be a matter of surprise that names are so often forgotten, when we consider that the individuals to whom they belong are before our eyes for hours, when the names are perhaps only before our eyes, or upon our ears, or upon our tongue, as many seconds. The skilful Mnemonist with a good Mnemonical Key at his command can accomplish many startling and practically useful things in the way of remembering names. But without a key, and with but an imperfect knowledge of Mnemonics, we may often obtain great aid by working upon Mnemonical principles. Those unacquainted with the multifarious Mnemonical manœuvres upon this point, cannot do better than use my "Golden Rule." Thus, "Observe" the individual; "reflect" upon his name; "link thought with thought"—that is, link him and his name together; "and think of the impressions"—that is, do not let the associations slip.

Sometimes a name may be remembered easily by associating it with a word somewhat resembling it in appearance. Thus my name, STOKES, looks very much like the word STORES. But mark, the comparison of the two words may be almost useless unless you associate the word STORES with MEMORY; that is, presuming you wish to remember "STOKES, TEACHER OF MEMORY." An association may be readily formed thus—he STORES the MEMORY, or MEMORY retains intellectual STORES.

Many exhibit peculiarities of mind which might be turned to very good account by the aid of this Science, but which are never recognised as being valuable, either by their possessors or by those around them. For instance, those who have the habit of punning, generally exercise it to the amusement or annoyance of other people; and it is not dreamed what a mighty Mnemonical agent they possess.

A well-used pun may often make

A very deep impression.

When giving a few remarks upon this subject to a class at the Colosseum, a gentleman inquired, "Well, Mr. Stokes, suppose I wanted to make anybody remember that your name is Stokes, and that you come from Brighton, how could I do it?"

Mr. Stokes. Perhaps you might be successful if you were to say, "Memory he stokes, and Memory he can brighten."

Pupil. Yes; I certainly think that punning might answer very well in that instance. But if I wanted it to be remembered that you are illustrating at the Colosseum, what could I say then?

Mr. Stokes. Oh, you could say, "He stokes his pupils' Memories; you'd better call or see 'em."

Pupil. Well, really, there appears to be no baffling you; but surely there are cases when punning would be very objectionable.

Mr. Stokes. Yes, you are quite right; but, you see, there are cases in which it is not objectionable; and then, if we like, we can introduce it. Because we cannot use it always, that is no reason why we should not use it at all. When it is not well to have a pun, we can adopt something else.

By rail we travel well on land,

But ships do best for sea.

Since the above took place, when teaching at the Polytechnic, a gentleman, with a partially suppressed smile which almost amounted to a laugh outright, inquired, "But how could you verbalise Mnenomically the fact that you are now here at the Polytechnic? That is a poser, is it not?" "No," I replied; "pardon me, but 'that is a poser' is a 'parroted' expression, and parrot is suggestive; allowing ourselves Mnemonical licence we might manage thus—"He STOKES a parrot's MEMORY, and makes her POLLY-TECHNICal!" The gentleman did not suggest any more posers the rest of the evening.

Those who indulge in rhyming, may gratify that propensity Mnemonically to an almost unlimited extent. The following is a little impromptu eulogium I wrote on Mr. Moon, the well-known blind teacher of the blind, of Brighton:—

'Tis sad to be deprived of sight,

To live as in perpetual night:

Yet 'tis a precious boon,

That those who never saw a ray

Of sunlight on the brightest day

Have an enlightening Moon!

When I was a lad, I was riding from Lewes to Chailey, in Sussex, in a kind of omnibus, and seeing the name of the proprietor in it, "WING," I could not refrain from pencilling the following underneath it:—

When travelling slow we often sigh,

And say we wish that we could fly;

But now we need do no such thing

Because, you see, we "go by WING!"

The subject of the doggerel seemed remarkably pleased with it, and I was told some time afterwards that when his vehicle was fresh painted he had my Anagram or Mnemonic preserved.

LOCAL MEMORY.

Many people complain that they are nearly sure to lose themselves" if they go into a strange locality, while others appear to find their way about almost instinctively. Want of observation is the main cause of this perplexity however, and unconscious watching is the supposed instinct. Those who frequently get into a state of reverie—who are what are termed "rapt thinkers," whose bodies are in one place and whose minds are quite in another—who step into puddles, tread on people's heels, and run against a lamp-post while making an apology—who walk under the heads of moving horses, and endanger their lives at every crossing, aware only of the fact when reminded by the refined intimation of an impetuous cabman.—people of this class have not in general good local memory. To insure good local memory, then, the eyes should be constantly open, however much the mind may be employed. We will suppose you are in a city you have never visited before, and are just going to take your first walk from your hotel. Look well at the house itself, observe the surroundings, and take notice of the conspicuous shops, churches, or other buildings; monuments, fountains, colonnades, arcades, etc., etc. Notice also the shape of the streets, their breadth, where they lead, and how they are intersected; and last, not least, turn round occasionally, so that you may obtain the return view. Every locality has two views, one from it, the other to it, and in many instances these are so very unlike, that the outward picture, seen the return way, would scarcely be recognised by the most observant stranger. Hence the great importance of obtaining the return view while on the outward way. In addition to obtaining the appearance of the streets, it is often desirable to possess their names also, which can generally be easily managed, either by looking for them or by inquiry. Then remark to yourself thus,—Broad Street leads to High Street, and High Street to West Street, etc., as the case may be. Many people who are very observant of places and of objects, never attempt to remember their names, and might almost live half a dozen years in one house without knowing the names of half a dozen streets in the immediate locality, although they could find their way about well. The inconvenience of not knowing the names of familiar streets is often felt to be very great, especially when an attempt is made to direct a stranger, as many instructions, such as first to the right, then to the left, then to the left, and cross over, etc., are likely to bewilder the most careful listener. It is important to remember that when asking a direction in the streets, an intelligent, reliable person should be selected. Policemen, postmen, or railway officials are usually the best, or, in their absence, butchers' or grocers' deliverers. A gentleman walk-ing in great haste, stopped suddenly and asked a person he met, "Can you tell me, please, about how far I am from the Railway Station?" "About half a mile," was the reply, and on went the gentleman. When he had proceeded "about half a mile" he inquired again, and was told, to his disgust, that he was a mile from it at the least, and that he must retrace his steps, as he was going from it!

To ensure the remembrance of localities, you should use my Golden Rule. "Observe" them; "reflect," or look mentally for their picture; "link thought with thought"—that is, link one place with another, "and think of the impressions"—that is, review the mental pictures while they are vivid and true.

To remember names of places. "Observe" the prace; "reflect" upon the name; "link thought with thought"—to the locality link the name; "and think of the impressions"—that is, think again of your associations.

Local Memory, or the remembrance of places, streets, etc., may often be made the means of aiding object, eventual, and ideal memory. One very effective way of using local memory is to take a mental walk. Suppose you are going out to make some calls; think first, of all the persons you wish to visit, and then decide in what order you will call upon them; and fancy you see yourself going from one place to another. Use my Golden Rule thus: "Observe" your starting-point; "reflect" upon that and your first call; "link thought with thought" continuously till you complete your list; and, finally, "think of the impressions; " see that you can make sure of going right. You may reverse the process of preliminary association, if you desire it, by thinking of all the persons upon whom you have to call, and then arranging them in a straight line, like a file of soldiers, but in such a manner that their succession will guide you to the right localities.

Use the Golden Rule thus: "Observe" who stands first; "reflect" upon him and who stands second; "link thought with thought," individual with individual, one after another, throughout the line, and "think of the impressions;" see that you can call your line in the right order.

When a number of things have to be purchased, they may be associated in such a manner as to give the locality in which they are to be obtained. In a similar way; use my Golden Rule thus: "Observe" the first object; "reflect" on that and the second; "link thought with thought," object with object, throughout, and "think of the impressions;" see that you can repeat the list without omissions or disarrangement.

THE REMEMBRANCE OF FIGURES.

The remembrance of figures is universally acknowledged to be extremely difficult; in fact, many highly intelligent minds are almost destitute of the power of retaining them. This is because the artificial signs we use to express numbers very frequently convey no definite idea to the mind. They do not suggest anything which the intellect can take hold of. Yet it is often desirable, nay, even absolutely necessary, that figures should be readily, accurately, and permanently remembered. No mere description will convey a true idea of the immense power which Mnemonics affords in this respect. A man must be an idiot who could dispute this, after witnessing such illustrations as those which I have given publicly, for years, at the Royal Colosseum, Royal Polytechnic, Crystal Palace, in Her Majesty's Schoolroom, Schoolroom, Whippingham, Osborne, and at numerous Literary and Scientific Institutions in London, and in various parts of the country. Students are constantly being "plucked" at examinations, through their inability to retain dates and figures: hence the innumerable attempts which have been made to prevent this, by the publication of "New and Improved Systems" of Mnemonics, which, after leaving their disgusted authors many pounds out of pocket, have been sold for waste paper, and have been circulated in single leaves from the counters of butter shops. That was the very best thing that could be done with many of them, there is no doubt, yet some possessed great merit. The vestiges of different methods which are sometimes to be seen heaped together, like bleached bones in the desert, become most uncomfortably suggestive of the thought of danger. I will therefore run no risk of adding to the resources of those who are engaged in simultaneously facilitating the spread of butter, and of Mnemonical Chronology.

A few suggestions, however, upon the remembrance of figures, which can be easily comprehended, and which may be applied occasionally, may be more serviceable than a "complete" System which, like others which have gone before it, through not being understood, might never be used at all.

If you are not acquainted with Mnemonics, do not, as a general rule, waste your time in endeavouring to learn dates, heights of mountains, lengths of rivers, etc.; you would be sure to forget them speedily. If, by way of experiment, you try to learn only a few—say a couple of hundred—you will soon find that this is correct. Wearying "din, din, din," upon the ear, and a multitude of brain-bewildering " comparisons," may enable a child to repeat its "task" (truly so named, and too often, as a kind of educational habit, injudiciously inflicted), or may "just serve to get a student through an examination; but the majority of impressions thus made will vanish almost before "the feat" has been accomplished; and the same results will be found to attend repeated efforts. When you must face the difficulty, try to learn numerical facts, as far as possible, by association. Anti-Mnemonists say the best way to learn dates is to "compare them with those you already know;" but this presumes that some are known, but suppose you do not know any; what can you do then? It is always safer in this matter to suppose that nothing is known, than to presume knowledge which does not exist. Yet, an intelligent man must not be treated like an idiot, and it therefore cannot be imagined that anybody who is at all enlightened would think that Nelson died in the fourteenth century, or anything of that kind. He would know, or, at all events might easily ascertain and remember, that it was in eighteen hundred and something. The mastery of this "something"—5—then, will constitute the remembrance of the date, which you may manage by counting the letters in his name, and then running your pen in reality, or in imagination, through the superfluous N, either at the beginning or end of his name, by which you would make it either Elson or Nelso, leaving five letters. Sometimes you can add to the name, thus—in 1806 Pitt died. Pitt contains four letters; so say, "Mr. Pitt," which will give six. You must proceed with care, however, or probably you will get into perplexity. Learn a few dates which appear to you to be easy to master in that way, first; and then you can manage to bring in another principle of association thus: in the same year as that in which "Mr. Pitt died, Fox died. You could easily fix that in memory by thinking of a Pit and a Fox together. When you have thus mastered a few dates, you can contrive to associate others with them, and then others with them, and so on, with comparative facility. This, however, is only limping along, compared with perfect Mnemonical progress. Many people can learn from one hundred and twenty to two hundred dates per hour by Mnemonics.

The plan of selecting words containing the requisite number of letters as substitutes for figures, may be applied for various purposes besides the remembrance of dates. For instance, suppose we wished to remember the number of a friend's residence was 45. We might observe that it was a "nice house," ,"—"nice," containing four letters, "house" containing five letters—45. Or if I wished you to remember that the number of my residence in Margaret Street, Cavendish Square, W., is 15. I might say, "It is here I teach,"—"I" containing one letter, and "teach" containing five letters—15.

There are many people who would rather use such means than learn a perfect System of Mnemonics, but they must always pay the penalty of want of readiness and loss of power, as it is impossible to master many things without a Mnemonical Key. Some people are tolerably quick, however, in applying even such imperfect suggestions as those just given; for instance,—a gentleman who was present at a street disturbance, taking a hint from one of my lectures, lodged the number of a policeman securely in his Memory, by observing that he saw him "twice struck with the five fingers of one desperado,"—251.

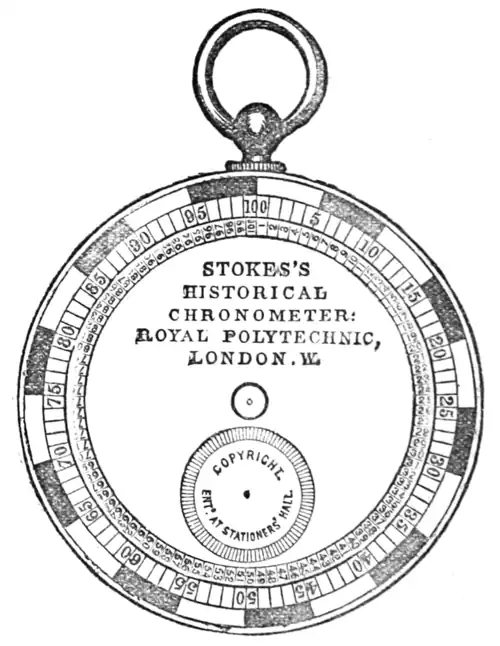

STOKES'S HISTORICAL CHRONOMETER.

it would be seen that there is a clear space of one year and three times five years—16 years—between the two events. The application of this remarkably simple contrivance involves the exercise of depicting, comparison, reflection, and association upon the sure basis of visual and local Memory.[1]

- ↑ Stokes's Historical Chronometer, mounted on cardboard with revolving centre, and an arrangement for Ancient and Modern History, with illustrations of the mode of application, etc., may be had price 18., or by post of the inventor for 14 stamps.