Ramtanu Lahiri, Brahman and Reformer/Chapter 10

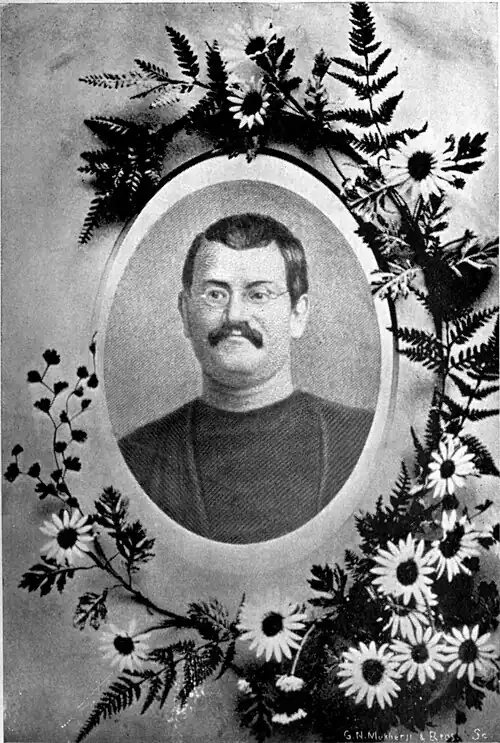

Kesava Chandra Sen (Keshub Chundar Sen).

CHAPTER X

Retirement in Krishnagar

Mr Lahiri’s health had partially been injured at Barisal, but it became almost a wreck in 1862, while he was in Krishnagar. Malaria had got into his system; and to expel it he took a change, going with his family to Bali. On retiring from the service with a pension, in 1865, he went at first to Bhagalpur, for its healthy climate; and then, returning thence, settled in Krishnagar. Here, in February, 1868, his elder daughter, Lilavati, now grown up, was married to an assistant-surgeon, named Tarini Charan Bhaduri. The marriage was not celebrated with Hindu rites. The bride and bridegroom were united by the father of the former, who gave away his daughter, calling God to witness and bless the union. A large number of guests, consisting of all the European and Indian gentlemen of Krishnagar, and such great men as Kesava Chandra Sen and Pratap Chandra Mozumdar, were present on the occasion. The Roy brothers of Krishnagar, famous for their generosity, were in their relative’s house, and took part in the preparations for the feast.

Mr Lahiri was greatly respected and loved, not only by his old pupils, but by all the common people too with whom he ever come into contact. The former loved and venerated him as a father: of these the late Kali Charan Ghosh was the foremost. What he did to show his devotion to his beloved teacher we will mention hereafter. There are many among them that learnt at his feet in youth, and who even now, when the old man is no more, are the best friends of his family, sympathising with them, and helping them in every way. Raja Peari Mohan Mukerji is one of these. But for his help, Sharat Kumar Lahiri, the second son of our hero, would never have prospered so well in his business.

The tablet in the Uttarpara School to commemorate Mr Lahiri owes its existence chiefly to the Raja. Happy the teacher who lives thus in the memory of his pupils; and happy are the pupils to retain in their hearts the image of their beloved instructor.

As to Mr Lahiri’s hold on the hearts of the common people, we give below what we ourselves have personally witnessed. We were once on a visit to him in Krishnagar. Having spent the whole day with him, we were proceeding in the evening to another friend’s house. When on the way we met some men belonging to the lower classes of society, who apparently were returning home from the bazaar. Curious to ascertain their opinion of the old man whom we so much revered, we entered into the following conversation.

We. Well, friends, do you live in Krishnagar?

People. Yes, sir, in a way—we live in the adjacent village.

We. Do you know Ramtanu Babu?

People. Whom?—our old Lahiri Babu? Who does not know him?

We. What kind of man is he?

People. Do you call him a man? He is a god.

We. How do you rank him among the gods who has cast off his Brahmanical threads, and eats fowls?

The men stared at me, and one of them said, “I see you do not belong to this part of the country, or you would not have spoken in this way. Casting off the thread and eating fowls are faults in others, but not in him. Whatever he does is good.” From the feelings of these illiterate people towards Mr Lahiri we can easily conjecture how greatly he was respected and loved by the educated portion of the Krishnagar community.

In August 1869 Mr Lahiri was blest with a grandchild: a son was born to Lilavati; and his Annaprashan, or the first putting of boiled rice into his mouth, was celebrated with great éclat.

About this time Ramtanu Babu was appointed guardian to the minors in the Mukerji family at Khetra Gobardanga. He was so well known for his high character and great abilities that the Government recommended him for this responsible post. We have already seen that wherever he went he did something worthy of being respectfully remembered, and this new place of his abode was not an exception. That he exercised a healthy influence on the minds of all classes of men there is apparent from the following lines quoted from the printed reports of the Khetra Brahmo Samaj:—“The well-known Babu Ramtanu Lahiri of Krishnagar was appointed by the Lieutenant-Governor as guardian to the minors in the family of the Zemindars of Gobardanga. During his stay here he was a great friend of a Brahmo youth of the Dutta family at Khetra, who found in him not only a wise adviser, but a ready helper too. It was a striking circumstance that an old and generally respected gentleman like Ramtanu Babu, setting at naught caste prejudices and all worldly distinctions, backed a young Brahmo in all his undertakings for the good of the village. Ramtanu’s influence was felt by almost every villager. Those who never before came within the precincts of the Brahmo Samaj became its regular attendants at his exhortations. The long-standing breach between the orthodox Hindus and the Brahmos in the village was healed by him, a friend to both parties.”

In 1869 Babu Ramtanu’s connection with the Brahmos and their Samaj became more intimate than before. The immediate cause of this was the marriage of Annadaini, the elder daughter of his departed cousin, Dwarkanath Lahiri, the genuine Christian, a short account of whom we gave at the close of the first chapter. She had after her father’s death been living in Calcutta under Mr Lahiri’s care, and as she had not embraced Christianity he gave her away in marriage to a Brahmo gentleman, named Haragopal Sirkar. Ramtanu visited Calcutta several times in 1869, and during these visits he came into a closer contact with the progressive Brahmos. In fact, there grew up an intimacy between him and them. We came to know him about this time. The first interview we had with him impressed us deeply with the loftiness of his sentiments, and this impression became stronger the more we knew him. Child-like simplicity was one of his characteristics. He was never sparing of praise or censure, as occasion required it. Whenever he found himself in the company of the Brahmos of Kesava Babu’s school he would say to them, “Ah, if Ram Gopal and Rasik Krishna were alive now, I would place you before them as the fruit of their prayers for a band of real reformers.”

We remember three incidents that happened at the time under review, which respectively show Mr Lahiri’s unflinching resolution to glorify God at the sacrifice of everything personal, his dread of speaking God’s name without due reverence, and the catholicity of his faith. To begin with the first. Immediately before Annadaini’s marriage, we were asked by him to make a list of the intended guests. We did so; and on getting the list he added a few names, but struck off the name of one of the most respectable men in Calcutta, with whom he was very intimate, so much so that the two used to pass a few hours every day in each other’s company. We were so surprised to see the name of such a great friend struck off that we could not help asking Ramtanu Babu the reason for it. But all he said was, “You need not know the reason, but please understand that I will on no account invite him to the wedding.” We had, however, not to remain long in the dark. We heard from someone that the cause of this exclusion was the fear lest this gentleman should behave irreverently during the solemn marriage service, as he had once behaved at the wedding of one of the daughters of Debendranath Tagore—the irreverent behaviour on that occasion was that he did not join in the worship preceding the marriage, but remained smoking in a side room. Not to be able to invite this beloved friend on this joyous occasion caused Ramtanu sincere grief, but he would sooner a thousand times forgo the pleasure of his dearest friend’s company rather than suffer his God to be insulted.

The second incident was as follows:—Once, a good singer being introduced to him when he was having his tea, he expressed a wish of hearing the man sing a Brahmo hymn. On this the latter commenced humming a tune by way of prelude. But he was too quick for Mr Lahiri, who had not finished drinking his tea, so he stopped the singer, saying, “Pray, sir, excuse me for a moment. I am not ready yet to hear my God praised.” After this he had the tea-cup removed, and then, standing up with his chadar across his shoulders—the humblest and most devout attitude of an Indian when he approaches his Maker—he joined in the devotion with hearty sincerity. And this is the third incident. One day, while returning from his usual morning constitutional, he asked me if I would begin the day by calling on one of God’s saints; and on my answering in the affirmative he, took me to a Christian missionary living close by, whom he embraced most affectionately. I was quite moved at the sight of two of God’s chosen people on earth making a mutual exchange of love and fellowship, which helped me in a great measure to realise the joyous meeting of God’s children in heaven.

Thus we see that Mr Lahiri was not a sectarian. To him Godliness was Godliness, whether found in a Hindu, Brahmo, Christian, or Muhammadan. He was the friend of good men, no matter to what religion they belonged. It often happened that when, on hearing that he had come to Calcutta, we tried to discover where he was, we found him a guest in some Hindu, Brahmo or Christian house. He was at home wherever good or saintly conduct ruled.

In 1870 he had an addition to his family, by the birth of another son, whom he named Benoy Kumar. Another son had been born to him in 1866; but the child died in its infancy at Bhagalpur.

Every social reform, every movement tending to elevate life and morals, was countenanced by Mr Lahiri, and he zealously led the way in all endeavours for the welfare of India. Female emancipation was one of these. The progressive Brahmos began to fight for it in 1872, and Mr Lahiri backed them. It was during his attempt to break open the doors of the Zenana that he became first known to, and then familiar with, the late Sir John Budd Phear and his wife, two real friends of the women of India. But whilst he desired that ladies should mix freely in good society, he was very prudent in selecting the company in which they should move. He strongly disliked their associating with men unworthy of the privilege. Let us here relate an instance of this. Once he went to hear one of Kesava Chandra Sen's lectures in the Town Hall, with his nieces, and had them seated in the front. At this one of his old friends present there, whom we have often named, Peari Chand Mitra, sarcastically spoke thus to him, “Well done, old Ramtanu! You are greatly in

Indumati Devi.

teresting the young men of Calcutta.” Mr Lahiri bore the joke with his characteristic patience; but on his return home he said to me, “Peari evidently wished me to introduce him to the girls, but I thought his levity made him an unsuitable friend.”

When the champions of women’s liberty started the “Bangamohila School,” or the school for Bengali ladies, Ramtanu Babu sent his second daughter, Indumati, there to receive her education. Miss Acroyd, subsequently Mrs Beveridge, who had come to this country to give education to the women at the request of Mr Manamohan Ghosh, whose guest she was, consented to superintend the working of the school. Mr Ghosh, as an inhabitant of Krishnagar, held Mr Lahiri in high esteem. Through him was the latter first introduced to Miss Acroyd. In time a great friendship grew up between Mr Lahiri and the lady; so much so that on the occasion of the misunderstanding that afterwards took place between her and Babu Kesava Chandra Sen he did not hesitate to speak to the latter very sharply.

Mr Lahiri was a great admirer of the feminine character. The ladies of the house where he used to stop while in Calcutta were very much attached him. They were always happy in his company; for it was his custom, after his short noonday rest, to get together all the ladies of the house in which he was guest for the time being and to be engaged with them in pleasant and instructive conversation. He would ask some one among them to read some portion of an interesting book; and was accustomed to use what was read as a text for an entertaining discourse. In this way the whole social and moral atmosphere of the house was benefited by his stay, even if only for a few days.

On the foundation of Bharatasram, or the “Indian Home,” by Kesava Chandra Sen, Mr Lahiri sent two of his nieces there to make it their home. He himself would occasionally come to the “Home”; for he loved Kesava Babu as the son of his friend Peari Mohan Sen, and honoured him as a pious man. We remember many occasions when he was deeply impressed and quite transported by Kesava’s eloquence in preaching. When any specially good and edifying words fell from the lips of the preacher Mr Lahiri, on quitting the hall of service, would, like a child, go about saying with great emotion, “Oh, what words of living truth come from Kesava!”

We have seen in Ramtanu the manifestation of no ordinary moral courage. It was this courage that bore him up in his many conflicts, social and religious. It gave him the pluck to be always frank and plain-spoken. No one, no matter how high his position might be, could do or say anything reprehensible in his presence without being instantly reproved by him. We have an example of this in the following anecdote:—One day he left the Brahmo “Home” with the intention of seeing a friend who was seriously ill. On his return from the visit some of the ladies of the “Home” crowded round him and asked many questions about the sufferer. One of them, hearing his name mentioned, burst forth into the exclamation, “What! You have been to visit a wretch like that? I never expected this.” The lady’s words jarred on the charitable feelings of Ramtanu. His friend, a retired Deputy Magistrate, had indeed been an ill liver in early manhood; but he had long learnt the error of his ways, and had been living a penitent, God-fearing life. So, irritated at the uncharitable remarks of the lady, Mr Lahiri said severely, “Madam, I know why you call my friend a wretch. But he is now quite changed. He has given his heart to God, and, even if it were not so, it would be wrong to revile him on his death-bed.” Saying this, he went on recounting many instances of his friend’s

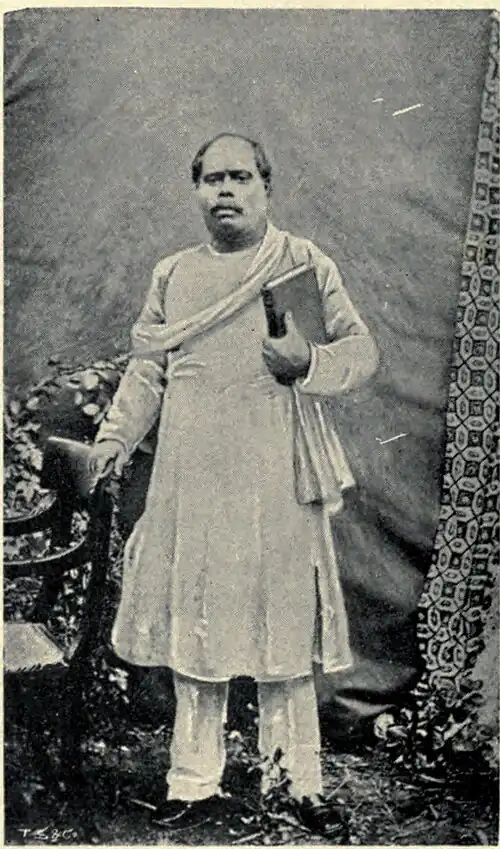

Professor Peary Charan Sircar.

1823–1875.

fidelity to conscience and faithfulness to his Maker. As he finished recounting each instance he asked the lady, “Madam, could you have done so much?” Each time, she was compelled by conscience to answer, “No!” At length he concluded, “Look here, madam, we look at the dark side of our neighbour’s character, and not at the bright. This is wrong. Man is frail, and so we should be judged as leniently as possible. Alas! it would be our ruin if God were as strict to mark, and severe to punish, our sins, as we are to notice the faults of our fellow-creatures.”

Mr Lahiri passed his life in Calcutta happily. He enjoyed the companionship not only of the progressive Bramos, but of many highly cultured, educated, and public-spirited men also, who used to meet every evening at the house of Baba Kali Krishna Mitra of Baraset, then an invalid. One of these was the late Peari Charan Sarkar, who, after having held the headmastership of the Baraset Government School, and subsequently that of the Hare School in Calcutta, was at the time a professor in the Presidency College. Peari Babu has left an imperishable name in the social history of this country. The institutions that owed their existence chiefly to him were the Hindu Hostel, which has now been replaced by the Eden Hostel, the Girls’ School at Chorbagan, and the first Temperance Society in India.

A man’s happiness can never be uninterrupted in this world of suffering; and Mr Lahiri’s comparatively smooth life at this time was ruffled by a circumstance the sad effects of which embittered the remaining days of his life. This was the serious illness of his son, Navakumar, when he was well on the way to gain distinction as a medical student. The young man was attacked by phthisis, and as soon as his old father learnt this, while in Krishnagar, he hastened to Calcutta, and after consulting Dr Norman Chevers, Principal of the Medical College, had his son removed from his lodgings to Babu Kali Charan Ghosh’s “Home.” Every possible care was taken to obtain a speedy recovery, but no improvement was made. At length the patient was taken to Krishnagar, and Indumati left her studies and went home to nurse him. This change of scene, however, did no good to Navakumar, and the climate of Bhagalpur was next tried. Indumati was there too, to attend on her brother.

Troubles are said to have come in a chain; and such was the case in Ramtanu’s family.

The master of the house had long been ailing. When in Calcutta before this he suffered from tertian fever, and had often to take to his bed. His daughter, Indumati, or one of his nieces, was always at his side reading something to him, or entertaining him by conversation. We remember an occurrence, at the time of which we are speaking, which showed that ill health had not in the least diminished the vigour and ardour of his soul. One day, when lying on his bed, he was hearing Annadaini read the Dharmalata, a Brahmo Bengali journal, and these words caught his ear: “There seems to be a close kinship between the passions; so that when we break the neck of one the others take fear and become weakened.” Casting off his lethargy, he got up from the bed; and with great excitement praised the thought in the passage, and went on repeating every word in it a hundred times. He asked his daughter and nieces who had used these words, and on their being unable to tell him he sent for me, as I was then living in the house. On my appearance the passage was at his request read to me; and I was asked who had expressed the sublime truth in it. I said it was Kesava Chandra Sen. Language fails to picture the delight with which he heard this. He loved Kesava, and great was his pleasure to find that it was his favourite orator who had given expression to such a beautiful thought.

The change to Bhagalpur at first proved beneficial to Navakumar. He recovered sufficiently to begin practising as a doctor. So, when Sharat Kumar came to Bhagalpur in July 1875, to recruit his health, his elder brother could join Indumati in caring for him.

Mr Lahiri was now happily living with the rest of the family at Krishnagar. But a calamity, the like of which he had not yet had to cope with, soon overtook him. One day in November, the same year, a telegram announced to him that his son-in-law, Tarini Charan, had committed suicide. Navakumar and Indumati, being informed of this, came to Krishnagar, and took the family thence to Bhagalpur. But nothing could repair the loss they had sustained. Mr Lahiri in a short time returned home with his wife and children, leaving Navakumar and Indumati at Bhagalpur. The former soon had a relapse; and the treacherous disease that had so long been preying on his system manifested itself in its worst form. Indumati’s devotion at this time was exemplary. Not to mention her denying herself every comfort while nursing her brother, she often had to fast for hours together, till at length her health gave way. In a short time she too was seized with consumption. We may well imagine the agony and grief of Mr Lahiri and his family when they received the terrible news that not only Navakumar, but Indumati also, were on the verge of the grave. They both were suffering from the same insidious disease, though in the one its fell work was slow, but not less sure, while in the other it progressed rapidly. In the middle of 1877 Mr Lahiri took both of them to Arrah for change. Here there was no sensible improvement. But at this time another dire calamity burst on the troubled family. Mr Lahiri’s youngest daughter, a girl of about two years and a half, died of acute fever. Indu grew worse rapidly after the shock of this catastrophe. In a month the doctors gave her up; and she was brought back to Krishnagar, there to sleep her last sleep. The whole family, including Navakumar, at this time again returned to their paternal roof.

The anguish which now tore the mother’s heart is beyond description. In addition to her mental sufferings she had, alone and unaided, to keep the house, besides nursing her dying children, so soon to pass beyond her care. It is a sad consolation to know that Navakumar and Indu, though knowing that their end must be approaching, were each most anxious for the other’s comfort. Many a time was each heard to ask his or her parents to give greater attention to the other. The brother knew that he was the cause of his sister’s untimely death; for if she had not undermined her health by incessantly watching by his sick-bed, and suffering so much privation, she might have had many years of life and its joys in store for her. And this thought made his heart bleed. He was unremitting in his inquiries about her, and in his prayers to his parents to look after her comforts. Indu in response, put her brother’s claims before her own. She, too, would ask her parents not to give so much time to her, but to attend to him whose life, she said, was much more valuable than hers. If Navakumar could have saved his sister’s life, or even prolonged its span a little, by giving his life for her, he would gladly have done so. Nor would Indu have been less ready to sacrifice her own little remnant of life to snatch her brother from the jaws of death. But they were soon parted, to meet again in a land where there would be no separation. At length the 4th of December dawned, the last day of Indu’s sojourn here. She wanted

Gangamati Devi.

to see her father, who was called in by Lilavati. Finding the dying girl in her last struggles he sat by her side; and by way of diverting her mind from her sufferings said, “Darling Indu, why did you send for me?” Indu opened her eyes and said, “Papa, sit by me. I am very restless.” On this Ramtanu, lovingly taking one of the girl’s hands in his, said, “Indu, we have done everything in our power; and do not know what more we can do for you. Pray to God that he may soon give you relief.” Indu, putting her clasped hands on her bosom, and looking up, said, “My God, give me a speedy deliverance.” Then looking at her father she said, “Farewell, papa.” The father said, “Farewell, my darling“; and then Indu’s spirit left its tenement of clay, and flew to its Maker.

It was while under the shadow of this trial that Mr Lahiri showed to the world of what stuff he was made. The fading away of a daughter like Indu from his sight rent his heart, but did not break his courage. When, at the moment of her daughter’s death, the mother wept and bewailed her sad fate, as it was natural she should do, her husband bravely consoled her. He prayed her to trust in God. He said: “You are putting your wishes before God’s. Bless His name that He, after giving our daughter a happy and peaceful deliverance from this world of suffering, has taken her into the home of peace. Do not lose the firmness of your mind. There is another child of ours, almost dying. We must devote ourselves to him. If you give way to grief in this way he will be neglected, and his life will be shortened. Come, let us go to him.” Ramtanu indeed knew the Divine secret of resignation to the will of God, by which man can master his grief. He believed that to mourn for the departed was a weakness, and that it betokened a heart rebellious against God. I have heard from a friend that Mr Lahiri, shortly after Indu’s death, invited a number of his friends, of whom my informant was one, to assemble in worship in remembrance of her. In the middle of the service the afflicted father uttered the girl’s name with a deep sob. He understood that he had betrayed a weakness; and so after service he spoke to his guests thus, “We say God is good; but our conduct hardly tallies with what we say. I just now showed unbelief in shedding tears for Indu. Why should I weep for her, when I remember that she is in His good keeping?”

Indu’s death accelerated Navakumar’s. From the moment of her death he never spoke another word. Every minute he thought of the sacrifices his sister had made for him. He was, as it were, stunned by grief, and then he would weep bitter tears of sorrow. Once a slip of paper with “Darling Sister,” and one or two lines written below, was found on his bed. His grief was violent, and his shattered frame succumbed under its weight. On the 15th of September 1878 he left this world of sorrows to meet his dear sister beyond the valley of the shadow of death. And that was a day of despairing grief, never to be forgotten by the Lahiri family. But it was also a day, too, that called forth all Ramtanu’s feelings of pious resignation. He showed a fortitude the like of which has seldom been known. When Navakumar’s dead body was in the house, and the bereaved mother lying swooning and senseless by its side, the father was whispering words of kindly solace into the ears of one of Babu Kartik Chandra Roy’s sons, who had been attached to the young man, and was bitterly mourning for him. At this very moment some young men arrived with whom Ramtanu had been accustomed to hold a religious service in his house on a certain day in the week, and this was the day for it. The young men had come in, not knowing the calamity that had befallen the inmates of the house. Mr Lahiri, seeing them step into the courtyard, ran up to them, and said, “I am sorry we cannot have the meeting here to-day. I made a mistake. I should have informed you of this before. Please excuse me.” On their asking him the reason he said, “Navakumar is just dead. His body lies in yonder room. Don’t go in, the sight will pain you.” They were all amazed to hear this from a father whose son was lying lifeless at that moment, but this pious man knew how to gain the victory over grief. Hearing of Indumati’s death I wrote a letter to him, blotted with many a tear, and expected that, in reply, he would give expression to thoughts of violent anguish. But I was wrong. The reply was thus worded:

“My dear Shibnath,—Thank you for your grief at our loss. Let us unite in thanking God for His having given Indu a deliverance from her sufferings.”

Another instance of his uncommon fortitude I mention here for the edification of the reader, that he may in this world of death and sorrow follow the footsteps of this great man. He had a friend at Bhagalpur to whom he regularly reported Indu’s condition when she lay on her death-bed at Krishnagar. One day his report was thus worded, “You will be glad to know that Indumati has no more to suffer. She is quite happy now.” The friend thought that by some unforeseen agency the girl had recovered. He was under this impression when the news of her death was brought him by some other person. Sages say that one should not shed tears for the departed; and Ramtanu did more than live up to this advice. He rejoiced in the sure conviction that the death of his dear departed children had made them partakers of the joys of heaven; and to lament their loss was in his opinion an unpardonable folly, combined with ingratitude of the blackest dye to the merciful Disposer of events. Actuated by this belief he would visit scenes of death and administer comfort to the bereaved.

I may mention an incident that occurred when I visited him one day in his lodgings in Calcutta, after the death of Navakumar and Indumati. I found him rather excited, and on my asking him the cause he said, “A few days ago a child in the adjacent house died, and since the occurrence my neighbours, male and female, have been lamenting their loss. I have been in there, and, calling the men to me, I have tried to console them. I have shown them that, as their dear one has been taken away from them by God for His good purposes, it is not right for them thus to lament their loss as those without hope. They reply by speaking of the transmigration of souls, and of the teachings of the Sastras; and so I have had to come away acknowledging my ignorance of these. Now, Shibnath, you know the Sastras, can you go and show the men from the teachings of their own sacred books that inordinate grief is a sin?” But I felt that it was useless to argue with them at such a time.

On the other hand, Mrs Lahiri was overwhelmed with grief at the loss of her dear children, and it became very painful for her to live any longer at the house in Krishnagar, where everything reminded her of them. So Mr Lahiri, giving up his guardianship of the young Raja, came to Calcutta in 1879, and took up his abode in a house at Champatola.