Ramtanu Lahiri, Brahman and Reformer/Appendix 2

APPENDIX II

A short sketch of the lives of some of the leading men in Bengal, who have been introduced to the reader in the foregoing narrative as friends of Ramtanu Lahiri.

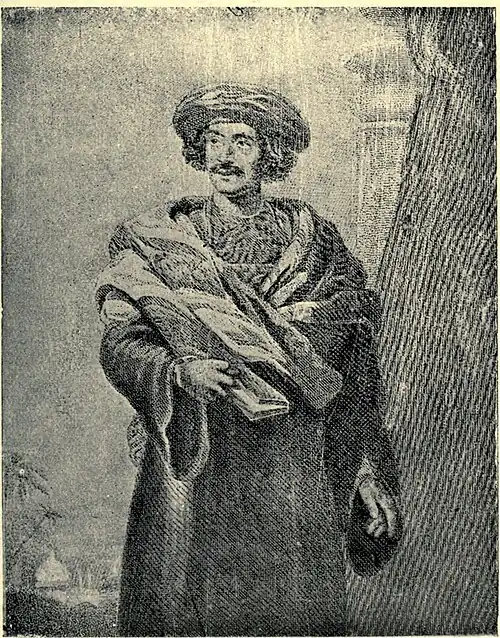

1. RAJA RAMMOHAN ROY

1774-1833

Raja Ram Mohan Roy.

1772–1833.

happiness, for he died soon afterwards. For ten years more Rammohan worked under Government; and then in 1813 retired, with the title of Raja, to devote his whole time to the moral and religious regeneration of his country. He came to Calcutta, and permanently settled there in 1814. He had in the meantime written many books on Monotheism. While at Rungpore he had given publicity to his Theistic doctrines, and thus incurred the bitter hatred of a host of orthodox Hindus of rank and eminence. It was his favourite amusement while there to invite Hindu Pandits and Maulvies to his lodgings, almost every evening, to listen to their discussions, and then to express his own opinions.

In Calcutta he got a few adherents from among the thoughtful and intelligent; though there were some men there who joined him from the selfish motive of having their worldly interests promoted by so clever and businesslike a man as he. The Alm’s Sobha, or the Association of Friends, was organised by him, in which the doctrines of Vedantism were expounded and discussed. Here is an anecdote illustrating Rammohan Roy's command of Vedic and Vedantic lore. One day in 1819 a Madrasi Pandit, Shubrahmanya Shastri, came to Calcutta and challenged him to a controversy, saying that, from the Vedas and Vedantas themselves, he would prove the reasonableness and the necessity of idol-worshipping. The challenge was accepted, and a day fixed for discussion. A vast meeting was held at the house of one Beharilal Choulay. Leaders of the Hindu Society, such as Radhakanta Deb, were present at the discussion; and Rammohan Roy expressed his views so convincingly that his antagonist had to acknowledge himself in the wrong.

The cause of Vedantic Monotheism became now stronger, and its advocate bolder. He founded the Brahmo Samaj for the worship of the one living and true God, and fearlessly declaimed against idolatry and superstition. But his attention was not monopolised by religious questions alone; he took a prominent part in the discussion of social matters as well.

In some of the preceding pages we have described how firm a stand he had made against Sati, and how he had done all in his power to promote a more liberal and enlightened system of education in this country. We described, too, what a bold front he had presented when his bigoted countrymen combined to persecute him. We followed him in his voyage to England; and, as we have said, he died at Bristol on the 27th of September 1833.

2. MAHARAJA SIR JATINDRA MOHAN TAGORE BAHADUR, K.C.S.I. (A pupil of Ramtanu Lahiri)

There is no name more familiar in Bengal, or for that matter in India, than that of Maharaja Sir Jatindra Mohan Tagore, the subject of this sketch. The Maharaja, who is the acknowledged head of the Tagore family, is the son of Hara Kumar Tagore, the eldest brother of the well-known Prasanna Kumar Tagore. The Maharaja was born in Calcutta, in the year 1831. In 1840 he married Srimati Troilukokali Devi, daughter of Babu Krishnamohan Mullick of Jagaddal, 24-Perganas. He is as sound a vernacular as he is an English scholar, and received his early English education in the Hindu College, where he studied till the age of seventeen, thereafter passing under the private tuition of Captain D. L. Richardson, the well-known scholar and poetical writer; the Rev. Dr Noah; Herman Geffroy (barrister), and other competent European educationists. The Tagore family has always been known for its devotion to Sanskrit learning, and the Maharaja is an accomplished student of that language. From an early period in life, it is said, the Maharaja displayed a marked taste for literary composition, both in English and the vernacular, and especially for poetry, as the verses contributed by him to the Provakar—then edited by the well-known Bengali poet, Isvarchandra Gupta—and to The Literary Gazette testify. His “Flight of Fancy”—which was printed strictly for private circulation, among friends only—contains verses written during youthful days. Some of these pieces have received the special commendation of well-known European authorities.

Few men have done more to improve and raise the character of the native stage in Bengal than the Maharaja, who has spent large sums of money in this direction. His interest in the native drama has not been confined to a mere patronage, for he has contributed by his pen a number of Bengali dramas and farces, among which the Bidya Sundar Natak occupies a foremost place, and has long been considered one of the classical compositions of the day. His talents have also been conducive to the improvemem of the orchestras, and have helped much in popularising Bengali drama in its modern form. In fact, the series of theatrical entertainments given at the Maharaja’s residence in Calcutta in past years really paved the way for the establishment of public native theatres.

But vernacular literature and the improvement of the native stage are not the only subjects which have engrossed the Maharaja’s attention, for he has lent his powerful influence, all through his busy and distinguished life, to raising the standard of Hindu society in Calcutta. He has always taken a deep thoughtful interest in the progress of the country, contributing to objects of public interest.

Maharaja Jatindra Mohan Tagore, who is at present one of the leading members of the native community of Calcutta, and is one of the largest Zemindars in these provinces, owning estates in eighteen different districts, came to the notice of the Government by his liberal treatment of his tenantry during the famine of 1866, by the interest he took in all movements affecting native interests, and by the assistance he rendered to Government in his capacity as Honorary Secretary to the British Indian Association. He has, in fact, from the commencement of his public career, been an active member of the British Indian Association, for, after filling for some time the office of Honorary Secretary, he was, in 1879, elected its President, an honour which has been conferred on him several times since. In 1870 the Maharaja was appointed a member of the Bengal Council, by Sir William Grey, and the services which he rendered in that capacity were so much appreciated that in the following year, when Sir George Campbell became Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal, he was nominated for a further term of membership, the high opinion entertained of him being thus expressed in a flattering letter: “Belvedere, Alipore,

“October 5th, 1871.

“My dear Raja,—I hope you will allow me to nominate you for another term in the Bengal Legislative Council. Your high character and fair mode of dealing with all questions render your assistance especially valuable, and I have much confidence that you are a man not bound to class interests, but prepared to look to the good of the whole community, high and low alike.

“Believe me, very truly yours,

“(Signed) G. Campbell.

Giving expression to a strong recommendation of Sir William Grey, Jatindra Mohan Tagore received the title, on the 17th March 1871, of Raja Bahadur. Sir William Grey’s recommendation was made in the following terms:—

“Babu Jatindra Mohan is a man of great enlightenment, and has had a thoroughly good English education. He is one of the leading members of the native community, is of unexceptionable private character, and is held by his fellow-countrymen in the highest respect. He is a useful member of the Council of the Lieutenant-Governor, and takes a deep interest in the progress of the country. He has estates in the districts of Midnapore, Faridpore, Murshidabad, Rajshahi, Nudea, and the 24-Perganas, and during his lifetime enjoys the revenue of the large estates of his uncle, the late Honourable Prasanna Kumar Tagore, in Rungpore and other places. He has always been found ready to contribute liberally to schools, roads, and other objects of public interest, both in Calcutta and in the districts in which his estates are situated, and has helped to promote science and literature amongst his countrymen by large contributions to that end. He regularly maintains eighteen poor students in Calcutta, and he fully accepted the obligation of his position in the famine of 1866, remitting the rents of his ryots, and feeding 250 paupers daily in Calcutta for a period of three months.”

The ceremony of investiture was performed by Sir George Campbell, who thus addressed Raja Jatindra Mohan Tagore on the occasion: “I have to convey to you the high honour which His Excellency the Viceroy, as the representative of Queen Victoria, has been pleased to confer on you. I feel a peculiar pleasure in being thus the channel of conveying this honour to you.

“You come from a family great in the annals of Calcutta—I may say great in the annals of the British Dominions in India—conspicuous for loyalty to the British Government and for acts of public beneficence.

“But it is not from consideration of your family alone the Viceroy has been pleased to confer the high honour upon you. You have proved yourself worthy of it by your own merits. Your great intelligence and ability, distinguished public spirit, high character, and the services you have rendered to the State deserve a fitting recognition.

“I have had the pleasure of receiving your assistance as a member of the Bengal Council, and can assure you that I highly appreciate the ability and information which you bring to bear upon its deliberations. Indeed, nothing can be more acceptable to me than advice from one like yourself. It is true we have had occasion to differ, and honest differences of opinion will always prevail between man and man; but, at the same time, I can honestly tell you that when we have been on the same side I have felt your support to be of the utmost value, and when you have chanced to be in opposition, yours has been intelligent, loyal, and courteous opposition.”

In April 1871 Raja Jatindra Mohan was exempted from attendance in Civil Courts. Six years later—i.e. on the 1st January 1877—on the occasion of the assumption of the Imperial title by her late lamented Majesty Queen Victoria, Lord Lytton conferred on him the title of Maharaja, the Sanad of which was presented to him by Sir Ashley Eden at a Durbar at Belvedere, in which he occupied the place of honour, on 14th August following.

The Maharaja was first appointed a member of the Supreme Legislative Council in February 1871, and so valuable was the help rendered by him in its deliberations, especially in the description of the provisions of the Civil Procedure Code Bill, that he was reappointed in 1879, and in 1881, as a member of the Legislative Council of the Governor-General.In the course of the debate on the above Bill, Sir A. Hobhouse, the legal Member of Council, said:

“Whatever can be said on that subject will be said by my friend, Maharaja Jatindra Mohan Tagore; for in committee he has supported the views of the objectors with great ability and acuteness, and, I must add, with equal feeling and moderation.” And again: “If the clause stood as in Bill No. IV. I confess I should not be able to maintain my ground against such an argument as we have heard from my honourable friend, Maharaja Jatindra Mohan Tagore. I have shown that conviction in the most practical way, by succumbing to his arguments in committee, and voting with him on his proposal to alter No. IV.”

The Maharaja had by this time become a “power in the land,” which he continues to be to this day, and there was scarcely a subject of public importance in which he did not take part, or upon which his advice and opinion were not sought. The Maharaja Bahadur was elected, by the unanimous voice of the European and native community of Calcutta, the President of the Reception Committee for the entertainment given to His Royal Highness Prince Albert Victor, during his visit to Calcutta. Honours thoroughly well deserved also commenced to fall on him fast. He was, in quick succession, created in 1880 a Companion of the Most Exalted Order of the Star of India. On the 1st of February 1890 the title of Maharaja Bahadur was conferred on him, as a personal distinction, and at the Durbar held at Belvedere, Sir Stuart Baily formally invested him with the new title, and presented him with a jewelled sword as a khillat. In 1891 the title of Maharaja was, in the Foreign Department notification, declared to be hereditary, and in 1892 the Maharaja Bahadur was formally invested with the hereditary title of Maharaja at a Durbar held in Belvedere, when a jewelled poshak, as a khillat, was presented to him by Sir Charles Elliott.

The Maharaja was a Justice of the Peace for the town of Calcutta; he is a Fellow of the Calcutta University; was Trustee of the Indian Museum (of which he was elected President in the year 1882); is one of the Governors of the Mayo Hospital; a member of the Asiatic Society, and a member of Committee and one of the Trustees of the Central Dufferin Fund. He was VicePresident of the Faculty of Arts in 1881-82. In 1882 he was elected President of the Faculty of Arts of the Calcutta University and of the Indian Museum, and was appointed by the Government of India to be a member of the Education Commission. He took a most active part in the discussion which preceded the Bengal Rent Bill of 1885. He has, besides, held, and continues to hold, many offices of trust and distinction. One of the wealthiest landowners of Bengal, he has been a liberal donor and subscriber to numerous works of public utility, among which may be mentioned the free gift to the trustees of his interest in the land on which the Mayo Hospital at Pathuria-ghatta is built. He has also subscribed liberally towards the cause of native education, not only in Calcutta, but in Bengal generally, several scholarships being founded to perpetuate the names of his distinguished father and uncle. He presented to the Calcutta University the marble statue of his uncle, the Honourable Prasanna Kumar Tagore, which is placed in the portico of the Senate House. Jointly with his brother, the Raja Sir Sourindra Mohan Tagore, he presented a piece of land to the Municipality of Calcutta for the construction of a square (to be named after his father), in which he has, at his own expense, placed a marble bust of his father. He has also founded, in memory of his mother, an endowment for the benefit of the Hindu widows of one lakh of rupees, under the name of the “Maharajmata Sivasundari Devi Hindu Widow Fund.” In 1893 the Maharaja Bahadur was appointed to be a member of the committee to inquire into the working of the Jury System.

In the debate in the House of Lords on the Indian Import Duties, on the 20th July 1894, Lord Roberts of Kandahar, in quoting a letter he had received from Maharaja Sir Jatindra Mohan Tagore, declared that “there was no more loyal subject or enlightened gentleman in Her Majesty's Dominions.” He is a man of mild disposition, but extremely independent in his views and liberal in thought. The late Sir Richard Temple said of him that “he combined the polished politeness of the old school of native with the educational accomplishments of the new,” without the forwardness and self-assertion which sometimes characterises the latter.A devout Hindu, a man of cultured tastes and polished manners, the Maharaja is universally popular, and is ever ready to assist in every good movement. He is a well-known social entertainer, and no one of distinction, either European or native, has ever passed through Calcutta without participating in his refined and cultivated hospitality. His recreations are mainly literary pursuits and musical entertainments, both vocal and instrumental, for which purpose he employs about a dozen musicians in his establishment. The Maharaja’s library is one of the most complete private collections in India; while his art gallery contains many fine pictures, including some genuine “Old Masters.” Latterly, owing to advancing years, he has not been very much in evidence, but he still takes a keen interest in all public movements of the day.

The Maharaja Bahadur, who has adopted his nephew, had four daughters, of whom only one is now living. He has five grandsons—namely, Babu Kumudprakash Gangoli, Babu Nalinprakash Gongoli, Babu Jaladhi Chandra Mukerji, Babu Kiranmali Mukerji and Babu Sheshprakash Gangoli, of whom Babu Nalinprakash and Jaladhi Chandra went to England, in company with the Maharaj-Kumar, on the occasion of the coronation of H.M. King Edward VII.

3. RAJA SIR RADHAKANTA DEB, BAHADUR, K.C.S.I. 1784-1867

In religion he was a bigoted Hindu—a strong supporter of the many prejudices and superstitions of his country. It was he who opposed—though in vain—the abolition of Sati, the suppression of polygamy, and the passing of the lex loci (the law conferring on native Christian converts the right of inheritance when their fathers died intestate).

He stood foremost in almost all educational movements. He was a director of the Hindu College and secretary to the School Society.

He was an Honorary Magistrate and a Justice of the Peace in 1855, and President of the British Indian Association from 1851 to his death.

The Government honoured him with the title, Raja Bahadur, in 1837; and he was the first Bengali gentleman that was invested with the title and decoration of the Star of India. He died on the 19th of April 1867, at the age of eighty-three.

4. DWARKANATH TAGORE

1794-1846

Dwarkanath was born in 1794. During his boyhood he was educated in English in Mr Sherbourne’s school; and he also acquired a good knowledge of Persian and Arabic. When a young man he read law with a barrister named Fergusson; and thus learnt Court business. Trading in indigo for some time, and not finding the business sufficiently lucrative, he left it when an opportunity for bettering his circumstances presented itself. Mr Plowden, then the salt agent, appointed him as his Dewan. After a few years’ service he returned, having saved money enough to start a mercantile firm, under the name of Carr, Tagore & Co. Besides that, he became the chief manager of a bank called the “Union Bank.” He was well known for his generosity and other qualities of the kind. He was very successful in making money, and was noted for his munificence. He soon became one of the wealthiest citizens of Calcutta, and the right hand of Rammohan Roy in all works of public utility. On his return from England, in 1842, he refused to perform the expiatory rite of Prayaschitra. He made two voyages to England, where he died, in 1846.

5. RAMKAMAL SEN

1783-184

Ramkamal Sen was Babu Keshub (Kesava) Chandra Sen's grandfather. He was born at Goriffa, a village near Hughli, in 1783. When seven years old he came to Calcutta for his education. But through lack of means he had to leave his studies rather early, and get into the way of earning something for himself. He worked for several years in a Hindustani press, after which he was appointed as a clerk in the Asiatic Society. But the posts which brought him wealth, rank, and honour, were the Dewani of the Mint, and the treasurership of the Bengal Bank. He joined in almost every endeavour for public good. He was a member of the Hindu College Committee, and the superintendent of the newly-established Sanskrit College. He was a member of the Medical Commission appointed by Lord William Bentinck. He compiled a very comprehensive English and Bengali dictionary. He died in 1844.

1791-1854

Mati Lal Seal, the founder and patron of the institution called Seal's Free College, was born at Colootola in Calcutta in the year 1791, and his position in society by birth was humble. But vast wealth, acquired solely by his own exertions, and the application of a considerable portion of it to charitable purposes, challenged the respect of all, the proud Kulin Brahman not excepted. His father, a dealer in cloth, died, leaving Mati Lal, then a boy of five years old, comparatively destitute. So the boy could get no better education than that available at a common patshala. But he knew how to make the best of small opportunities; and he soon got a thorough knowledge of the vernacular, and of accounts. He got married at the age of seventeen, and accompanied his father-in-law in his pilgrimage to the shrines in the Northwest. His travel matured his mind, and gave him a great deal of practical wisdom. Returning to Calcutta, in 1815, he managed to get some insignificant post at Fort William. But while here he hit upon a plan which became the foundation of his future fortune. This was the idea of buying and profitably selling bottles and corks. He carried on this business together with his work in the fort, and soon he became the possessor of capital enough for more venturesome and profitable transactions. One of these was the “banianship” of foreign ships lying in harbour in Calcutta—a business that brought large returns. He was always honest; not a single rupee came into his hands in an unfair way. He was polite, affable, and benevolent. “Seal’s Free College,” founded in 1842, and supplied with ample funds, bears testimony to his liberality. He died in 1854, at the age of sixty-three. The Seals of Colootola (who only a few years ago ranked in wealth next to the Maharaja of Burdwan) were his descendants and heirs.

7. HENRY LOUIS VIVIAN DEROZIO

1809-1831

This clever Eurasian was born at Entally, in Calcutta, in 1809. He was of Portuguese extraction. His father held a respectable post in a mercantile firm in the city, and was respected by the community. Vivian had two brothers and two sisters. Both his brothers were older than himself. Their end was sad. The eldest became spoiled and useless. The second, Claudius, was sent by his father to be educated in Scotland; what became of him there is not known. The elder sister died when seventeen years old, but the younger, Amilia, lived with Vivian, and was a devoted sister.

Young Derozio was brought up at a school at Dharmtala, kept by a Mr Drummond, a man deeply learned in literature and science. Drummond was a poet too. It was said of him that difference in religious opinions had caused a breach between him and his relations, and that consequently he had made India his home. The freedom of thought that had been the cause of the French Revolution was fully developed in him, and the European residents of Calcutta were afraid to send their sons to his school. Derozio’s genius, of which we have said so much, bore the deep impress of Mr Drummond’s influence.

Vivian Derozio, leaving school at the age of fourteen, worked in his father’s office for some time, and then went to Bhagalpur, to live with his aunt. It was his custom, while here, to ramble along the banks of the Ganges, deep in meditation, and to pore over the pages of all manner of works in literature and science. He wrote articles for The Indian Gazette, edited by Dr Grant. It has been said that he at this time also wrote such a clever criticism on Kant’s philosophy as to astonish everyone. It has been sometimes observed that a philosopher cannot be a poet, but Derozio was an instance to the contrary—he was both a philosopher and a genuine poet.

On returning to Calcutta he was appointed to the fourth mastership of the Hindu College. How he did his work, in what friendly relations he stood with his pupils, how their minds were broadened under his influence, and how he sent out a band of young Bengalis as harbingers of light to their benighted countrymen, we have already mentioned. He died on the 23rd of December 1831. The reader has already been told how anxiously and affectionately he was watched and nursed by his pupils while on his death-bed.

8. THE REV. DOCTOR KRISHNA MOHAN BANERJI

1813-1885

The growth of the banyan-tree, with its far-spreading branches from a tiny seed, is hardly more wonderful than the development of the humble Kulin Brahman boy, Krishna Mohan Banerji, into the Rev. Dr K. M. Banerji. He first saw light in 1813, in his maternal grandfather’s house at Shampukur, Culcutta. His parents being very poor, he had in his childhood to endure every sort of privation. At the age of six he was sent to one of Mr Hare’s patshalas. Here his talents were noticed, and Mr Hare, in 1822, took him into the "School Society's School," at present known as the "Hare School." From here the young lad went to the Hindu College in 1824.

His love of learning, even when a boy, was so great that he never willingly absented himself from school. Many a morning would he trudge thither without even a handful of rice to fortify him for the hard work of the day. To relieve his mother he often cooked the evening meal.

He belonged to the first class of the Hindu College when Mr Derozio got his appointment there, and an intimacy soon grew up between them. When the Academic Association was organised, Krishna Mohan took the most active part in it. When he finished his collegiate education, in 1829, Mr Hare appointed him second master of his school. While here he took up journalism, and in May 1831 he started The Inquirer, to wage war against Hinduism. In the month of August, the same year, he had to suffer expulsion from home, being the scapegoat of his beef-eating friends. Not that he was less forward than they in ridiculing Hindu prejudices and superstition; not that he refrained from offending the orthodox community by eating and drinking what was abomination to them; but on the evening in question he was absent from the scene of a disturbance which his friends created by throwing beef from his house into his neighbour's.

Expelled from home he sought shelter in his friend Dakhina-ranjan's house. How long he remained there is not known, but we suppose that he had soon to leave his friend's roof through fear of causing a dissension between him and his father, who did not like his son to associate with him, much less to receive him as his guest.

Krishna Mohan was homeless for some time, but never dispirited or down-hearted. He edited The Inquirer still, and gave vent to his rancour against Hinduism in language more bitter than ever. He boldly attended Duff's and Dealtry's lectures, and freely ate and drank with them. The 17th of October 1832 witnessed his baptism. Dr Duff's and Mr Dealtry's influence, conjointly with that of Captain Corbyn and Colonel Powney, who were sincere Christians, and with whom Krishna Mohan freely mixed, brought about his conversion.

This was the turning point in his life. His countrymen now hated and opposed him more than ever; but, undaunted by all their attempts to crush him, he rose higher and higher, till he attained a position of great public influence. His wife, after hesitating for about four years, joined him. She too accepted Jesus as her Saviour, and the husband and the wife lived peaceful Christian lives for many years.

Krishna Mohan was one of Dr Duff's converts; but, believing the doctrines of the Church of England to be more Biblical than those of the sister Church of Scotland, he soon joined the former; and was ordained deacon in 1837. He was then appointed pastor of Christ Church, Cornwallis Square. He made two converts: his younger brother, Kali Charan, and Ganendra Mohan Tagore, the only son of Prasanna Kumar Tagore.

Mr Banerji left Christ Church in 1852, for a professor's chair in Bishop’s College, which he occupied till 1860. Here is a list of the chief works which have made him famous in Bengal:

1. Thirteen volumes of the Encyclopedia Bengalensis, in English and Bengali.

2. An essay on female education.

3. The six Darsanas, or Schools of Hindu Philosophy.

4. The Aryan Witness.

5. Numerous text-books and pamphlets in Sanskrit, and lectures in English.

He resigned the professorship in the Bishop's College in 1868, and became a pensioner of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. Subsequently, he became the Bishop's Honorary Chaplain.

In 1867 the Calcutta University conferred on him the title of Doctor of Laws. In 1878 he acted as President of the Index Association. In 1880 he was elected a Municipal Commissioner, but he resigned the commissionership in 1885, when the Bengal Government interfered with the sanitary arrangements of the Corporation. He died on the 11th of May in that year.

Dr Banerji was a very eminent linguist. He was learned in English, Latin, Greek, Hebrew and Sanskrit; and in Bengali and Uriya he was an acknowledged authority. He was for many years an examiner in Bengali, both for the Government and for the University of Calcutta in 1869 the editor of this work had the privilege of being examined by him, and passed, in this language. In The Aryan Witness he showed an acquaintance with the chief Semitic and Coptic languages. He understood business well; and ably managed his son-in-law Ganendra Mohan Tagore's property during his absence in England. He managed also his own affairs so well as not only to be comparatively wealthy himself, but to be able also to meet with a free hand the calls of charity. He lived and died respected and loved by all.

9. RAM GOPAL GHOSH

1815-1868

This early friend of Dr Banerji, and not unlike him in intellectual capacity and reputation, distinguished himself chiefly in the domain of politics. He was born in October, 1815, in Bechu Chatterjee’s Street in Calcutta, and was the grandson of Dewan Ramprosad Ghosh, and son of Gobinda Chandra Ghosh, a dealer in cloth in the China Bazaar. Their family house was near Trebeni, in the Hughli District. Ram Gopal prosecuted his studies in the Hindu College, and was one of the first to follow Mr Derozio’s teachings with regard to the superstitions of his country, denouncing the religion of his forefathers, and living rather an Anglicised life. Before finishing his college course he, in 1832, secured a good position in the business world, through Mr Hare’s recommendation, with a merchant who wanted an assistant. He not only served his master to his satisfaction, but before he was twenty gained so much experience in mercantile affairs as to write a series of articles on Inland Transit Duties. He soon became a partner in a European firm; and a few years afterwards, probably in 1848, he started business independently, under the name of R. G. Ghosh & Co.

He did not, however, in the cares of his extensive business, forget his duties to his country or to his friends. He played the most important part in all social movements; and he was ever ready to help those whom he loved, to the best of his power. Once, Babu Ramtanu Lahiri being in straits, his friend Ram Gopal Babu unable to render him enough pecuniary assistance, got him appointed as a Munshi to a merchant. Besides this, when another friend of his, Rasik Krishna Mullick of whom we have often spoken in our narrative, was seized with an illness from which he never rallied, and came to Calcutta, Ram Gopal Babu took him in and entertained him in his garden-house on the river bank, and made lavish arrangements for his treatment and comfort. But the crowning act of his liberality and friendship was that, when lying on his death-bed, he called for the bonds his friends had given him for the loans advanced to them, and tore them to pieces, thereby freeing those friends from all liabilities. The sum covered by the bonds was about 40,000 rupees.

Ram Gopal was truthful and honest, as well as liberal. To show this we will relate the following incidents:—

When his grandfather died, and his father had to perform the Shradh, the orthodox Brahmans and Kayasthas threatened that they would neither eat at the latter’s house, nor receive his gifts, because his son was a heretic and a Mlechchha. This was the greatest disgrace a Hindu could imagine; and the old man, with tears in his eyes, told his son that matters might be mended if the latter would only disown having done anything anti-Hindu. But Ram Gopal was too conscientious to yield. He burst into tears and said, “Father, I am prepared to suffer everything for your satisfaction, but can never tell a lie.” This instance of firm adherence to truth was noised abroad; and he rose the higher for it in the estimation of the world.

On another occasion, when, through failure of business, he was involved in debt from which he seemed powerless to extricate himself, some of his friends advised him to make all his property benami. But he would not entertain the idea, and said firmly, “I would be the last man to deprive my creditors of their due.”

Babu Ram Gopal Ghoshas we have said before, always directed his energies to the improvement of his countrymen. He edited the journal called Gyananneshur, and organised a “Society for the Acquisition of General Knowledge.” He founded the “Epistolary Club,” and started The Bengal Spectator, which we have previously mentioned. He supported Dwarkanath Tagore and Dr Goodeve in their proposal to send Bengal medical students to England to complete their education there; and when the four selected students were about to embark he cheered and encouraged them to try the perilous voyage.

He was a genius in politics, and took a leading part in all political movements of the day. Mr Adams established the “Indian Association” in England, and managed it according to the plan suggested by him. But we have yet to mention the most brilliant gift he possessed—namely, that of genuine oratory. He was the Demosthenes of India; and his speech against the Government Resolution not to permit the burning of the dead at the Nimtala Ghat, also that on the renewal of the Charter Act of 1853, that on the memorial to be raised in honour of Sir Henry Hardinge, and that on the administration of Lord Canning, were masterpieces of oratory.

Government appreciated his merits, and as a reward offered him the second judgeship of the Small Cause Court in Calcutta, but he respectfully declined the offer. He was a member of the Calcutta Police Committee of 1845, of the Small-pox Committee, of the Central Committee for the Collection of Works of Industry and Arts for the London Exhibition in 1851, the Paris Exhibitions of 1855 and 1867, and the Bengal Agricultural Exhibitions of 1855 and 1864. He was a member of the Council from 1848 to its dissolution, in January 1855; a very active member of the Bengal Chamber of Commerce; a Fellow of the Calcutta University, the Agri-Horticultural Society, and the District Charitable Society; an Honorary Magistrate; and a Justice of the Peace for Calcutta, and a member of the Bengal Legislative Council from 1862 to 1866.

As a promoter of education, a patriot, a politician, a speaker, a social reformer, and a successful merchant, Babu Ram Gopal Ghosh was one of the foremost men of his time, and he did much for the advancement and enlightenment of Hindu society. We have derived the information on which this memoir is founded from Mr Buckland’s “Bengal under the Lieutenant-Governors.”

The career of this great man closed in January, 1868. 10. RASIK KRISHNA MULLICK

Rasik was born in 1810. He was a Tili by caste, and belonged to a very respectable family. There is unfortunately not much to write of this man. Not that his life was barren of incident, but that we have not a full and reliable account of it. He may have been less forward that Krishna Mohan and Ram Gopal in demolishing the fortress of Hindu prejudices and superstitions, but none the less zealous in fighting for what seemed to him to be right. Ram Gopal’s speeches against Hinduism were fiery and stirring, Krishna Mohan’s were full of humour and satirical eloquence, while Rasik Krishna’s were calm and thoughtful. That he was a true disciple of Derozio, and could not tolerate idolatrous Hinduism, is evident from the following incident, that happened in his student life:—Once, when summoned as a witness before the Supreme Court, and, according to the custom, required to ratify his deposition by swearing on a copper vessel containing a few leaves of the tulsi dipped in a little Ganges water—the most sacred symbols with Hindus—he boldly said that he was not a Hindu, and would not take the required oath. The whole court was thunderstruck to hear this. The Hindus present shut their ears with their hands, and hissed in scorn.

When Rasik, on leaving college, enrolled himself as one of the zealous workers in the cause of social and religious reform, his mother tried by every means, reasonable or unreasonable, to throw obstacles in his way. She thought him possessed of some wicked spirit, to destroy whose influence she once contrived to make her son eat a white powder, which proved to be poison. Poor Rasik fell insensible, and while in this condition arrangements were made to send him by boat to Benares. But when the boat was in readiness, and his hands and legs were tied, to make him incapable of resistance, fortunately his senses returned. He broke the bonds asunder, ran out of the house, and took lodgings at Chorbagan, which eventually became the rendezvous of all the young men of Derozio’s school.

Rasik Krishna began the world as a teacher in the Hare School. Then he got an appointment as Deputy-Collector of Burdwan. Here he worked for many years, with a good name for probity and fairness. He was often offered bribes by the amlas of the Burdwan Raj; but nothing could induce him to swerve an inch from an impartial course.

By a fortunate coincidence, Babu Ramtanu Lahiri came to Burdwan when his friend Babu Rasik Krishna was Deputy-Collector there. They lived there again in close companionship. Ramtanu would not take any important step without consulting Rasik. The one held the other as his guide, philosopher, and friend. In after years, long after Rasik Babu had departed this life, we have often heard Mr Lahiri quote him as an authority.

In 1858 Babu Rasik Krishna came to Calcutta as an invalid, and lodged in Babu Ram Gopal Ghosh’s garden-house at Kamarhatti. It was there that he breathed his last, leaving Ram Gopal and Peari Chand Mitra his executors.

11. SHIB CHANDRA DEB

Babu Shib Chandra Deb was born at Konnagar, on the 10th of July 1811. His father was a well-to-do gentleman of good character. After receiving some education at home he was, at the age of thirteen, sent to the Hindu College, where he finished his studies. He was one of Mr Derozio’s pupils and admirers.

After leaving college he worked for some time as a computer in the Survey Office, at a salary of thirty rupees a month. Then as Deputy-Collector he was posted to Balasore, in 1838, and to Midnapur in 1844. From there he was transferred to Alipur, in 1850.

Having served the Government for twenty-five years he retired, in 1863. But in this last period of his life he was most active in improving the condition of his native town—which had, even before that, been benefited by him in many ways. It was to his endeavours that the Konnagar schools, both English and vernacular, the railway station, post office, Brahmo Samaj, and dispensary owed their origin. He established a Girls’ School there at his own cost.

He died on 12th November 1890, leaving a widow and a large number of children and grandchildren. 12. HARA CHANDRA GHOSH, BAHADUR

He too was a student of the Hindu College and a disciple of Derozio. He was born in 1808, and he died in 1868. He took a leading part in the Academic Association.

Lord William Bentinck offered him his Dewanship, but he could not accept it owing to the opposition of his mother. In 1832 he became Munshi of Bankura, and proved himself so trustworthy that he was promoted within a year to the rank of Sadar Amin. In 1838 he was transferred to Hughli. He gradually rose in rank, and in 1844 he came to Alipur as principal Sadar Amin. In 1852 he became Junior Magistrate of the Police Court in Calcutta, and in 1854 Judge of the Small Cause Court there.

He was a learned man himself, and encouraged the progress of learning in general. He was a friend of the cultured, and joined in every undertaking for the intellectual and moral improvement of his country. He took under his tutelage the youthful Kristo (Krishna) Das Pal, afterwards famous as the editor of The Hindu Patriot, and treated him as if he had been his own son, and he supported many other poor and helpless boys.

There was great lamentation among his friends and relatives on his departure from this world, on the 3rd December 1868. On 4th January 1869 a monster meeting took place, in the Town Hall, to devise the best way of perpetuating his memory. A marble statue was erected and placed at the Small Cause Court. It still stands there, as a tribute of public gratitude to a man who devoted his life to the faithful service of Government and his countrymen.

13. PEARI CHAND MITRA

1814-1883

The reader has often heard in the foregoing chapters of this man, famous for his intelligence and his warm desire for the public good. He was born in Calcutta, in 1814, and educated at the Hindu College, where, in 1835, he gained all the honours and distinctions within his reach. He then got employment as Deputy-Librarian in the Calcutta Library, which now is housed at the Metcalfe Hall. From Deputy-Librarian he became Librarian, then Secretary, and at length Curator, and the Curator’s post he held till the end of his life. His connection with the library gave him an excellent opportunity of acquiring knowledge and developing his mind, and he was a regular contributor to all those magazines that were edited by Ram Gopal Ghosh and Rasik Krishna Mullick.

It was Peari Chand who gave a happy turn to the Bengali literature of the time, by editing, conjointly with Radhanath Sirkar, a small monthly journal in good colloquial Bengali. This was in the nature of a reaction against the highly classical and Sanskritised style of Pandit Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar and Akhoy Kumar Dutt, who, by using too many long and pompous Sanskrit words in their Bengali writings, had given the language, in the opinion of many, a heavy and ludicrous character. Peari Chand, under the nom de plume of “Tekchand,” also wrote in the same style the first Bengali tale, “The Spoiled Pet in a Rich Family,” which is still regarded as a good sample of light and pleasing literature. He subsequently wrote many works in Bengali, neither in this light style, nor in the pedantic Johnsonian style that had become unpopular with the majority of the reading public, but with an easy and graceful flow of language.

He, with his brother, Kessori Chand, wrote in English the biographies of David Hare, Ram Kamal Sen, and Mr Grant.

He understood mercantile matters thoroughly. He at first carried out some successful speculations in partnership with his friend, Babu Tarachand Chakravartti, and on the death of that gentleman, in 1855, he took the business into his own hands. His profits were great, and so wide was his reputation in the mercantile world that he was appointed to be a director of many firms.

He was public spirited, and took a leading part in all movements for the public good. He was a member of the Social Science Association, the Agri-Horticultural Society, the District Charitable Society, the School Book Society, and of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. For two years he served his country as a member of the Bengal Legislative Council. After his wife's death, in 1860, he, to some extent, lived a retired life, and devoted much of his time to the study of Spiritualism. When Colonel Olcott and Madame Blavatsky founded the Calcutta Theosophical Society he joined it. He died on the 23rd of November 1883, to the regret of his many friends, who put up to his memory in the Metcalfe Hall his portrait in oils, and in the Town Hall his bust in marble.

14. RADHANATH SIKDAR

1813–1870

He was one of the pupils of Derozio, and an intimate of Ramtanu. He was born in 1813, of a Brahman family, which had gained considerable distinction during the latter years of the Mughul rule. Sikdar means “Police Commissioner,” and the family had this name because the heads of it were successively the Heads of the Police under the Nawabs of Bengal.

He was a student of the Hindu College, where he gained a Senior Scholarship. He had a great taste for mathematics, and had Dr Fuller, then the first mathematician in India, for his teacher. He, like all other followers of Derozio, came forward as a deliverer of his country from the trammels of ignorance and superstition. He was always true to his word. Neither fear nor self-interest could induce him to swerve an inch from what he thought was right. He always detested what he felt to be wrong; and a proof of this was the celibate life he lived, in spite of the wishes of his mother, whom he both loved and revered, for his early marriage. He believed that it was wrong to force a girl eight or ten years of age, through her parents, into a wedlock entailing responsibilities the nature of which she did not understand; and as young Hindu maidens of a riper age were not available in those days he altogether shelved the question of marriage.

He left the Hindu College on being appointed a computer in the G. F. Survey on thirty rupees a month. He gradually rose in the Survey Department, and was transferred to the North-west. His strong will, great self-respect, and exceptional cleverness, secured for him the esteem and friendship of both the European and the Indian gentlemen with whom he came into contact. That he was not a man to be easily snubbed is evident from the following incident, which happened when he was a surveyor at Dehradun. The District Magistrate, Mr Vansittart, on one occasion, while on tour, forced some of Mr Sikdar’s men to work as his coolies. Mr Sikdar, greatly offended at this, rushed out of his bungalow and brought the coolies back, with the Magistrate’s things on their shoulders, protesting against the illegal proceedings of the latter. Mr Vansittart was in a fury, and he prosecuted Mr Sikdar for having obstructed a public servant in the discharge of his duties. The case came up before another magistrate, and, fearful of the consequences, many of Mr Sikdar’s friends advised him to apologise; but he did not yield at all. He remained firm to the end; and, though he was fined 200 rupees for the offence, his resistance gave rise to a strong agitation, the result of which has been that the practice of forcing men to labour has died out among Government officials.

The highest post he occupied was the head computership, the monthly salary for which was 600 rupees. When he returned to Calcutta, a few years after his father’s death, in 1853, his friends found that he was perfectly anglicised in customs and manners.

We have in Peari Chand’s “Life” referred to Mr Sikdar as his colleague in improving Bengali literature. To write chaste Bengali in a style so easy that even illiterate people might understand it became the latter’s chief aim; and before sending his articles to the monthly periodical of which he was joint-editor he would first read them to the ladies of his house, whose understanding of them was the criterion for their admission into its columns.

He died in 1870 at his garden-house near the French station of Chandernagore.

15. RAJA DAKHINARANJAN MUKERJI

1814–1878

The career of Dakhinaranjan was not of much importance, and we give his life only because he was an early friend of Mr Lahiri, and a year or two older. He was born in the Tagore family, the son of Babu Surjya Kumar Tagore’s daughter. He cared very little for his father, who, living as a dependant on his father-in-law, was rather looked down upon by his son. In fact he cared for none of his relations; and, therefore, in eating and drinking with Europeans, and imitating their manners, he was more forward than many of his friends.

He had an affectionate heart; and he loved his early friends sincerely. Here are two instances of it. When Krishna Mohan Banerji had to leave home Dakhinaranjan gave him shelter, and on his father having one day, in his absence, driven his friend away he left home and lodged in a house near Mr Derozio. The other instance was his making an anonymous gift of 1000 rupees to Babu Tarachand Chakravartti, when the latter was in some difficulty. Tarachand Babu was for some time in the dark as to whence the help came; and it was only after much inquiry that he found out who his benefactor was.

As long as Mr Derozio lived Dakhinaranjan was as well behaved and pure in principles as his companions; but after his death Dakhinaranjan became a changed man. He became intemperate and licentious, and his early friends all forsook him. To redeem his character to a certain extent, it was said that this change or deterioration in him was the result of his having been poisoned by his relations with a drug similar to that administered to Rasik Krishna. The strain on his intellect was too great, and he gave way to temptation. After some time he seemed to have regained his former strength of mind and a mastery over his passions, and was again hailed by his friends as their lost brother reclaimed. But again a circumstance happened which for good alienated them from him. Into the well-known details we need not here enter. His friends shunned him now, never to receive him back. He felt greatly pained at this, and left Calcutta. When he did so is not known to us. It seems likely that he left Calcutta for Lucknow in 1851 or 1852. He was at Lucknow during the Mutiny, and as a reward for his having helped the Government to restore peace he received a jagir, and the title of Raja. In old age his noble sentiments and aspirations, which seemed to have been long dead, revived, and he once more devoted himself to the good of his country. Through his exertions was founded the Talukdar’s Association of Oudh, on the model of the British Indian Association; and he did much to remove the racial antipathies between the English and the Indians. He edited a periodical dealing chiefly with political matters. But a change of fortune embittered his last days. He somehow lost the Government’s favour; his honours were taken away from him, and he died of a broken heart, in 1887.

16. TARACHAND CHAKRAVARTTI

17. PANDIT ISHWAR CHANDRA VIDYASAGAR

1820–1891

The name of this illustrious man will never be forgotten. It has been the lot of few in India to leave such a bright example after them as he has left. He was born in 1820, in the Midnapur district. His parents were very poor. He had a great desire to acquire knowledge, and underwent many privations when a student. He studied in the Sanskrit College from 1829 to 1841, and then became head pandit in the Fort William College. In 1848 he published the translation of the “Vetal Panchabinsati,” or the twenty-five stories related by a demon to Vikramaditya. In the same year he was appointed assistant-secretary to the Sanskrit College, but resigned his post in a year owing to the Council of Education not accepting some of his proposals. In 1849 he was appointed head assistant to the Fort William College, and the next year he became a professor in the Sanskrit College, of which he got the principalship in 1851. The college is largely indebted to him for the prosperity it enjoys. In 1855 he was appointed special Inspector of Schools for the Hughli, Burdwan, Midnapur, and Nadia districts. The new appointment did not interfere with his duties in the Sanskrit College; and he received a total salary of 50 rupees. It was under his auspices that many vernacular schools, both for boys and for girls, were established in the districts under his inspection; and it was in connection with these that some friction arose between him and the then Director of Public Instruction. The differences grew into a serious misunderstanding, and he resigned his appointments in 1858. But he continued to enjoy the confidence of the Government. On the establishment of the Calcutta University he was nominated as one of its Fellows and a member of the Board of Examiners. In January 1880 he was created a C.I.E.

Miss Mary Carpenter, in her mission to Indian ladies in 1866, chose him as her chief counsellor; and while driving with her from the Bally Station to the Uttarpara Girls’ School he had a bad fall, the effects of which lasted till the day of his death, which happened on the 29th July 1891. Vidyasagar was a great educationist. He opened the Metropolitan Institution, and its branch schools in different parts of Calcutta, with the object of training the young on an improved system. He wrote a graduated series of school-books in Bengali and Sanskrit. The greatest reform, for which he will always be remembered with admiration, was that made with regard to Hindu widows. He showed from the Shastras that the remarriage of these was not anti-Hindu. Great was the battle he had to fight with his fellow-pandits, many of equal rank with himself, and bitter was the persecution that he had to endure. But undaunted he carried on his noble work, and the remarriage of widows was sanctioned by legislature.

He was a great philanthropist. Distress in any form always touched his heart, and he was quick to remedy it. The upper and the lower classes were equally the objects of his charity. He opened his purse to Michael Madhusudan Dutt as readily as to the poorest creature that drew breath in the slums of Calcutta.

He was a good disciplinarian. He knew how to punish intentional neglect of duty. Under the simplicity of a child he hid the sternness of a judge, which won him the respect of everybody. His death was felt as a national calamity. He was a first-class educationist, reformer, and philanthropist, and we fear India will never see his like again. His life has supplied materials for many a voluminous treatise; and lest we should be lost in the immensity of the subject we have confined ourselves only to the simple enumeration of some of the most important events in this great man’s career, and the most salient points of his character.

18. AKHOY KUMAR DUTT

1821–1886

Ahkoy Kumar has left a name behind him for his literary works and the improvements which Bengali society owes to him. He was born in 1820, at a village in the Nadia district. After he had obtained a rudimentary education in Bengali he was, in 1830, taken by his father to Kidderpur, his place of business. Akhoy’s guardians and friends were for teaching him Persian; but the boy showed so great a desire to learn English that they had at length to decide in its favour. For some time he learnt it at home, with the help of his father’s English-speaking friends; but he felt that his progress was by no means satisfactory, and therefore got himself, without his father’s knowledge, admitted into the Free English School at Kidderpur started by missionaries. His guardians, afraid of keeping him under missionary influence, made arrangements for him to go to Calcutta and to attend Gaur Mohan Addy’s school, then one of the most efficient educational establishments in the city. This was when he was in the sixteenth year of his age. While here he showed an insatiable thirst for knowledge, and eagerly grasped every kind of information within his reach. But his father’s death, three years after, compelled him to leave school. Poverty, with all its concomitants, made life miserable. But the young man did not give in. While working for his mother’s and his own subsistence, he tried as hard as before to acquire knowledge. He made Sanskrit his chief study, and made great progress in it. In 1840 he succeeded in getting a teachership in the Tatwabodhini School. He began with the monthly salary of eight rupees, which in a short time rose to fourteen rupees. In 1843 the Tatwabodhini Patrika was started, and he became its editor. His connection with this paper was the source of his future greatness. To acquire a sound scientific knowledge he, as an ex-student, studied botany, physiology, and chemistry in the Medical College. Besides this, he devoured the contents of the useful works in the Tatwabodhini Library, and he edited the Patrika in a way that showed that the right man was in the right place. His style was superior to that of any other Indian journalist of the day. The books he wrote were full of profound thought, clothed in chaste though somewhat bombastic language; and in a short time he became an authority on Bengali literature. His chief ambition was to spread the light of knowledge among his benighted countrymen. Rank and wealth had no attraction for him.

But the most important of his achievements was to free the Brahmo Samaj from its thraldom to the Vedas, which it had hitherto held to be of Divine inspiration. The falsity of this position struck Akhoy Babu; and after much conflict with Babu Debendranath Tagore he, in 1850, was able to convince his friends of the fact that the Vedas were not the word of God. He was chiefly instrumental in reducing the Brahmo creed to its present form.

On the establishment of the Calcutta Normal School he was appointed one of its teachers; but this new employment did not materially interfere with his editing the Tatwabodhini Patrika. His constitution however, never a strong one, gave way one day in 1855, when he was worshipping in the Brahmo Samaj. He fell down in a fainting fit. With great care he was brought to; but his brain was affected, and he was compelled to give up writing. Even in this invalid state, however, he compiled his famous and learned work, “The Worshippers of God in India,” with the help of an amanuensis.

He passed his last days in retirement in his bungalow at Bally. Here he died on the 14th of Jaishta 1886, leaving behind him many thoughtful and instructive works in Bengali.

19. RAJA DIGAMBAR MITRA, C.S.I.

1817–1879

This eminent man was born at Konnagar in 1817, educated in the Hindu College, and began life as a teacher in the Nizamat School. After holding several posts of trust under Government, in 1838 he became manager to the Kasimbazar Raj, under Krishnanath Kumar, husband of the late Maharani Surnamai. He so ingratiated himself with the Kumar as to receive from him a present of a lakh of rupees. With this large sum of money Digambar got on well in speculations in indigo and silk; but the failure of the Union Bank gave an overwhelming blow to his prospects. From the effects of this, however, he recovered by selling off his garden-house at Bagmari, and buying with the proceeds of the sale the Sunderban lot Dabipur, in the 24-Perganas. He was a Zemindar now, and gained distinction in public life by taking a prominent part in the political questions of the day. He began as assistant-secretary to the British Indian Association; and in 1864 he sat on the Malarious Fever Commission appointed by Government, and in the Bengal Legislative Council. He extended his estates by purchasing some lots of ground in Orissa, in 1866; and, learning in his visits the ravages that famine was making there, he urged upon the Government the necessity of relief, and himself rendered valuable services as a member of the Relief Committee. In 1869 he became Vice-President of the British Indian Association, and in 1870 again took his seat in the Lieutenant-Governor’s Council. When the local Government entered into an investigation of the causes of the epidemic fever that had for years been ravaging Lower Bengal he showed that the chief cause had been the obstruction to free drainage offered by railways, and roads connected with them. In 1872 he was appointed, for the third time, a member of the Legislative Council, and acting President of the British Indian Association. He became Sheriff of Calcutta in 1874, and was made a C.S.I, in 1876. The title of Raja was conferred on him the next year. Before this he had succeeded in getting himself appointed President of the British Indian Association.

Raja Digambar Mitra left this world on the 20th of April 1879, after a brilliant career. He rendered eminent services to his country through the British Indian Association; and with the chief Government officials his opinions were of great weight.

A few years before death he had to suffer a great bereavement in the accidental death of his only son. Another calamity which embittered his last days was the permanent insanity of his wife.

20. BABU PRASANNA KUMAR TAGORE, C.S.I.

This worthy member of the illustrious Tagore family was born in 1803, and received as good an education as was available in the country for one of his parentage. He at one time thought seriously of taking up the work of social reform; but the conversion of his only son to Christianity produced in him a reaction; and after that he became averse to all radical changes in society.

Though the property left by his father was very large, and though he had considerably increased it by the intelligent management of his Zemindaries, still, to enrich himself further, he practised as a pleader in the Sadar Diwani Adalat. His success in his profession was remarkable, and his annual income as a pleader ranged between one lakh and one and a half lakhs of rupees. He did much for the spread of English education. He was a member of the Hindu School Committee, and of the Council of Education; and when the Calcutta University was founded he became one of its Fellows.

Lord Dalhousie appointed him clerk-assistant to the Imperial Legislative Council. Subsequently, he sat as a member of the same Council. He was made a C.S.I., and died in 1868.

He has left a name behind him for charity. He not only patronised the Mayo Hospital, but, at his own cost, established charitable dispensaries in his Zemindaries in the Mufasal. He placed three lakhs of rupees in the hands of the Calcutta University, for a Law Professor to lecture on Hindu Law. To commemorate him, a marble statue has been placed in the vestibule of the Senate Hall of the university.

21. MAHARSHI DEBENDRANATH TAGORE

1818-1905

Maharshi Debendranath Tagore, the son of Dwarkanath Tagore, was born in 1818, in the family mansion in Calcutta. Having received his early education in the school founded by Raja Rammohan Roy, he joined the Hindu College, and was one of the fellow-students of Ramtanu, though he was not one of those attached to Mr Derozio. In the formation of his early religious impressions he was influenced not so much by the broad and reformed views of his father as by the nursery tales and traditions held sacred by the old ladies presiding over his father’s house. And so he grew up a quiet young man, holding the religion of his forefathers in great reverence, and practically mindful more of his worldly than spiritual interests. But certain unexpected circumstances, which we need not mention here, wrought a change in him on attaining to manhood. Thinking little of the world and its attractions he devoted himself, as he thought, to the service and glorification of his Maker. In 1839 he founded the Tatwabodhini Sabha, or Society to Promote the Knowledge of Truth, and in 1840 the Tatwabodhini School for the study of the Vedantas. The religious movement that originated in him was purely national, for amidst all the preference that was then being given by the educated to the manners and customs of the West, and the air of defiance young Bengal had assumed against the old religion of his country, Debendranath’s principle was strict conservatism. He tried to establish the belief that Monotheism was the religion of the Vedas and Vedantas, and that following the doctrines propounded in them was the surest way to salvation. To him, ancient India was the cradle of all that was good in religion and morals, and he bent his whole soul upon the revival of that spirituality which had marked the Vedic ages.

In 1842 Debendranath joined the Brahmo Samaj, and finding that, through want of proper management, it had lapsed into a comparatively lifeless society, he devoted all his energies to its improvement. The number of its members gradually increased, till it rose to 573 in 1847.

But a difference of opinion crept into the Samaj, and after a good deal of discussion the majority of its members, in 1850, decided that neither the Vedas nor the Upanishads were to be accepted as infallible, and that the natural intuitions of the soul, together with the highest spiritual ideals reached by philosophy and religion in India, or anywhere else, should be regarded as man’s guides.

Maharshi Debendranath gave an example of commendable integrity when he impoverished himself by paying off certain heavy debts which he was not legally bound to pay. The debts had been contracted by his father in a way to leave him free from all liability, and he could have repudiated them. But conscience told him of his moral duty, and he paid them off to the best of his ability. The consequence was that he had to part with much valuable property.

We judge of a Guru generally by the pupils he brings up; and so in Debendranath’s case we must make obeisance to the greatness of his mind, and to the spirituality of his soul, when we bear in mind that Kesava Chandra Sen received his religious instruction from him. Saintly, philosophic, and gifted with oratorical powers of the highest description, he commanded general respect and admiration.

By dint of economy and good management he recovered his fortune, and again took his place among the richest in Calcutta. Some of his sons have made great names for themselves—Dwijendra as a philosopher, Satyandranath as the first Bengali civilian, and Robindranath as a poet and prose writer in Bengali. The title Maharshi, given to Debendranath by his people, means the great Rishi. He died on 19th January 1905.

22. KESHUB (KESAVA) CHANDRA SEN

1838-1884

Keshub’s natural powers were extraordinary, and his eloquence wonderful. He would have taken a place among the really great if there had been in him less of a zealot, and if he had a little clipped the wings of his imagination. But, on the whole, he is worthy of our admiration, as having left his mark on his time.

He was born in 1838, and admitted into the Hindu College in 1845, which he left in 1853 to join the newly-founded Metropolitan Institution. On the failure of this he returned to his old alma mater, in 1854.

An incident now happened which had a great effect upon him. He was caught using unfair means to pass one of his college examinations, and turned out. He had all along been quiet and well behaved, and great was his shame and bitter his grief at the occurrence. He forsook his former companions, repented of his folly, and spent much of his time in prayer and meditation. He joined the Hindu College again as an ex-student.

At this time he often sought the society of the Reverend James Long, of the Church Missionary Society, and Dr Dutt, the Unitarian Missionary, and with them he founded an association called the "British India Society." A night school in Keshub’s dwelling-house at Colootola was an offshoot of this.

In 1857 he, with a few friends, organised a religious association, called the “Good Will Fraternity.” It was at the meetings of this society that his oratorical powers were first called forth and improved. It was here also that Maharshi Debendranath Tagore first came to know him. Soon after this Keshub formally joined the Brahmo Samaj. In 1859 the Brahmo School was founded, and here both Debendra and Keshub used to lecture in English and Bengali to college students, the subjects being always religious. This was the means of attracting many intelligent young men towards the Brahmo Samaj.

In 1860 the Sangit Sabha, or “Association for Mutual Improvement,” was established by Keshub Babu in his house. It met once a week, and the members talked over their spiritual experiences. It was about this time that, urged by his guardian, he accepted a post in the Bengal Bank at a monthly salary of thirty rupees. But though tied to the desk his energy remained undiminished, and showed itself in the publication of many pamphlets, of which “Young Bengal, This is for You” was one. It was about this time also that he started The Indian Mirror and a Bengali newspaper, both of which he ably conducted.

The year 1865 saw a great revolution in the Brahmo Samaj. Keshub, though he had for so many years sat at the feet of Debendranath, could no longer put up with his conservatism. Debendranath maintained that widows should not remarry, and that caste distinctions should not be done away with, while Keshub held exactly opposite views, and thus a breach took place between them.

In 1866 the Brahmo Samaj of India was started, with Keshub as secretary. It had no connection with Debendranath or his Samaj, which now became designated as the Adi Brahmo Samaj. It was purely eclectic, taking its doctrines from the Bible, the Koran, the Zendavesta, and the Hindu Shastras; and eight missionaries were appointed to preach this new faith.

The erection of the Brahmo Mandir in Machua Bazar Street, Calcutta, was completed in August, 1869, and since then the Samaj founded by Keshub Babu has met there.

In 1870 Keshub went to England, and was favoured by Her Majesty Queen Victoria with an audience. After his return he established a training school for Indian women, an industrial school for young men, and the Brahmo Home. The cause of temperance, too, had his attention. It was chiefly through his exertions that the Civil Marriages Act became law in 1872.

The hitherto uninterrupted success attending Keshub’s career as a reformer put him rather above himself, and it is said of him that, during the latter part of his life, he tried to impress the belief on his fellow-Brahmos that he was their spiritual Guru, appointed by God to bring them into his fold, and that he was to command and they were to obey. Giving his daughter in marriage to the Maharaja of Kuch Behar, in May 1878, against the representations of his friends and admirers, was the first step he took in that direction.

From this event dated his claims to superhuman powers, his visions like those vouchsafed unto Jewish prophets of old, and his rhapsodical addresses.

In 1881 he proclaimed the New Dispensation, a medley of many religions and of Hindu Joga and Bhakti. Referring to this time Max Müller said, “He sometimes seems to me on the verge of the very madness of faith.” Pouring ghee over a blazing fire, Keshub thus addressed Agni: “Thou art not God; we do not adore thee. But in thee dwells the Lord, the Eternal, inextinguishable flame. O thou brilliant Agni, in thee we behold our resplendent Lord.” (Buckland’s “Bengal under the Lieutenant-Governors.”)

To Keshub’s credit as a preacher be it said, that but for him Brahmoism could never have made so much progress in India. Though he seemed to revere Christ, he opposed somewhat the spread of Christianity. When many a Hindu mind had been cleared of the superstitions of ages, and prepared to receive the seed of the Gospel, in came Keshub, dispossessed the Christian missionary of the soil he had fitted for cultivation, and used it for his own purposes.

Before taking leave of him let us quote a few words about him from Buckland’s “Bengal under the Lieutenant-Governors.” These are: “His neo-Hinduism was never fully developed, but had he lived a few years longer it is more than probable that he would have discarded his earlier conceptions and risen to the rank of a powerful reformer, like Chaitanya. But as it has happened, Chaitanya’s followers are counted by the million, those of Keshub by scarcely as many hundreds.”

Hard labour, and anxiety to regain the prestige he had lost, told on his constitution, and he died of diabetes on the 8th January 1884.

Ishwar Chandra Gupta was born at Kanchrapara, in B.S. 1218. His father was very poor, and maintained his family with the small salary of eight rupees he got by working in a factory. Having lost his father at the age of ten, he lived at his maternal grandfather’s house in Calcutta. It is said that while here he wilfully neglected even the very slender opportunities he had for acquiring knowledge, and he entered the world with a smattering of Bengali—his sole stock-in-trade. His muse, though unschooled, enraptured me with her melody, and through her inspiration he ranked as one of the greatest poets of the day. His compositions in prose, also, were equally charming. He had a ready wit, and an inexhaustible stock of humour, together with the power of giving a solemn turn to the commonest things in nature.

In 1830, at his friend Jogendranath Tagore's instance, he started the Probhakar, a Bengali weekly, containing excellent contributions in poetry and prose. But he had to give it up after two years, owing to the death of his friend and patron. It was then brought out as a daily; and it was as its editor that he attained his highest fame and influence. There grew up in Bengal a school of poets after his fashion. Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, the Sir Walter Scott of Bengal, and Dina Bandhu Mitra, the famous dramatist, and writer of the “Nildarpan, or the Indigo Planters’ Doings,” received their first lessons as writers from him.

Ishwar wrote many learned books too in Bengali, in a style both easy and eloquent. He was a favourite not only in all literary circles, but in the Zenana too, and ladies were often heard repeating his poems with great delight. He died in 1865. 24. MICHAEL MADHUSUDAN DUTT

1824–1873

The name of Michael Madhusudan Dutt will ever remain enshrined in the memory of his countrymen. He has given the Bengali language a new life and a new power, and adorned Bengali literature with a new store of gems, largely gathered from the Persian. He was born on the 25th of January 1824, in his ancestral home at a village in the Jessore District. He was much petted by his parents; they never said nay to whatever he wanted, and this over-indulgence was the chief factor in the composition of his impulsive and volatile character in manhood. In his very boyhood he learnt to seek his own comforts, and to gratify his own inclinations, entirely disregarding the wishes of his parents. His father, Rajnarain Dutt, a Vakil of the Sadar Diwani Adalat, brought him at the age of twelve to his lodgings at Kidderpur, and had him admitted into the Hindu College, where he read till 1842. During his career as a student he took the foremost place in every class through which he passed and distinguished himself as a writer in verse and prose. Mathematics he detested. He had many frailties. He lived after the lusts of the flesh; but he never allowed his propensities to interfere with his acquisition of knowledge. The one great peculiarity in his nature was that he scorned to tread the beaten track. To do something new and unprecedented was always the goal he had in view.

He left the Hindu College in the highest class, and became a Christian in February, 1843. He then joined the Bishop’s College as a theological student. During the four years that he studied there he attained proficiency in. Greek, Latin, and Hebrew. Later on he acquired French, German, and Italian. But his restless nature was still dominant in him, and ambition led him to Madras. While in Bengal he was, through the munificence of his kind father, never in want; but bereft of this while in Madras he had to suffer more or less from poverty. He could, however, though with difficulty, manage to make both ends meet by writing for the newspapers. He had married an English lady, but he forsook her for a countrywoman of hers, and came back to Calcutta, in 1856, to find that his parents had died during his absence, that his nearest of kin had cast him off as an apostate to the faith of his fathers, that his ancestral property had been seized by others, that many of his college friends had left Calcutta, and that their places had been taken by strangers. His prospects were indeed gloomy now; but he was soon helped out of his difficulties by one of his early friends, Gurudas Baisak, who got for him a clerkship in the Presidency Magistrate's Court, from which he soon rose to the post of interpreter. It was Gurudas again who introduced him to the Raja of Paikpara, and to the Maharaja Jotindra Mohan Tagore, when they started the Belgachia Theatre. An English translation of the Sanskrit drama Ratnavali, from the pen of Michael, was acted with success on 31st July 1858. This was followed by two Bengali dramas, Sarmistha and Padmavati. His next undertaking was a poem in blank verse, "Tilottama Sambhab." This was the first attempt at Bengali blank verse, and its novelty, together with its true poetic sentiments, startled the public. Next followed that stirring poem of his "The Megnadbadha Kaliya," the most precious treasure in Bengali literature; and the farces Akaylkibole Sabhayata and Bura Salikar Gharhe, exposing respectively the vices of young Bengal and the hypocrisy of the old Hindu. To the list is to be added his later productions, Biranagana Kalya and Krishna Kumari.

It was a lucky circumstances that his occupation as an author did not entirely take away his mind from worldly concerns. He put forth his claim to his paternal property, and succeeded in proving it. His circumstances were prosperous now; and if he had been less extravagant, and less ambitious, he might have passed life in ease. But rest he was never to enjoy. His whims got the better of him again, and he embarked for England in June 1862. There he entered Gray's Inn. He passed five years in Europe in great want and privation. He was involved in debts, and life seemed a burden to him and to his family. They had not the means of paying their passage back to India, and their bones would have lain far away from its shores if Pandit Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar had not helped them with the sum necessary for their voyage home.

Michael came back to Calcutta as a barrister in 1867. But law was not his proper element. He was literally a briefless barrister; and, after a period of untold misery, he died, in the Alipur General Hospital, in June 1873. It is said that when about to die he sent for the Rev. Krishna Mohan Banerji, and received absolution from him.

1824–1861

We have in Harish another self-made man. From the humble position of a Kulin Brahman’s son, born in the most indigent circumstances, he rose to an eminence which many might covet. He first saw light in a humble house at Bhawanipur, a suburb of Calcutta. He attended a Free School for five years, and was obliged to leave it at the age of seventeen years, with an unfinished education, in order to earn his own livelihood. The first post he got was worth ten rupees a month. But he soon found how to improve his circumstances. He gained admission to the office of the Military Department as a clerk on twenty-five rupees a month. Here he worked uninterruptedly for many years, his salary before his death being 400 rupees a month.