Punch/Volume 148/Issue 3853

CHARIVARIA.

We hear that the crews of the German aircraft which pay us a visit from time to time have a grievance. They complain that, if their activities lead to loss of life they are called "baby-killers," while, if they only take the life of a blackbird, they are jeered at; and it is really very difficult for them to know what to do.

⁂

The Minister of Public Instruction in Saxony has issued an order to the effect that the sons and daughters of alien enemies shall be expelled from all the schools in the Kingdom. This attempt to protect English children from imbibing Kultur is not the only instance we have had of the marked friendliness of the Saxons towards ourselves.

⁂

"A defeat of Great Britain," says the Vassische Zeitung, "would really be hailed as a relief by Australians and Canadians." The Germans certainly have a knack of getting hold of information before it reaches even those most intimately concerned. For example, the Canadians at Ypres, and the Australians in the Dardanelles, appear to have been appallingly ignorant of their real attitude towards the Mother Country.

⁂

"We have already, since the War began, advanced much in the world's respect and admiration," says Die Welt. Die Welt is, we imagine, the world referred to.

⁂

We like to see that even diplomats can have their little joke now and then, and the following passage from an interview with the Ex-Khedive of Egypt appeals to us:—"I was in Constantinople," said Abbas II., "recovering from a wound inflicted by a would-be assassin, when the War broke out. I intended to leave immediately for Egypt, but the English advised me not to hurry back, telling me that the weather was too hot for me in Cairo."

⁂

According to the Kaiser's wireless press "the corner-stone of the German Library, an eminent work of peace in the midst of war," was in Leipzig last week in the presence of State dignitaries and men of science and art. We suspect, however, that there are not a few citizens who are complaining that they asked for bread and received a stone.

⁂

A correspondent of the Cologne Gazette was, with other journalists, recently entertained to dinner in a French villa by the Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria. "The party, while dining," we are told, "talked of the defects of French taste, and Prince Rupprecht said that French houses were full of horrors." True, O Prince, but the French are determined to drive them out.

⁂

Which reminds us that a critic was rather brutally hard on some of the pictures at the Royal Academy when he said, "At Brulington House the horrors of war are brought home to us."

⁂

"£50,000,000 FOR TURKEY

from our own correspondent."Daily Mail.

While this gives one a good idea of the princely salaries which our contemporary must pay its correspondents, it also looks like a fragrant instance of trading with the enemy.

⁂

Persons liable to super-tax, Mr. Lloyd George tells us, now number 26,000. Might it not be worth while, with a view to increasing their numbers, to offer a bonus to all who join their ranks?

⁂

From The Grimsby News:—Wednesday was a beautiful, bright, sunny day, and in the afternoon we observed that Mr. Richard Mason, the district county coroner, availed himself of these enjoyable conditions to drive out, accompanied by Mrs. Mason, to the Riby Wold-road Farm of Mr. Addison. Here he held an inquest... Mr. Mason must have many pleasant drives in the spring and summer as his district embraces 91 parishes, and many of the wold villages are very beautiful, and well worth a visit." One can almost hear Mr. Mason saying to his wife, "It's a fine day, my dear. Let's hold an inquest."

⁂

We do wish our newspapers would avoid ambiguity. The following headlines are sure to be quoted by the enemy press:—

"TO END THE WAR SPEEDILY.

Mr. Bonar Law's Way.

CRUELTY TO PRISONERS.

Daily Mail.

⁂

The offspring of The Daily Chronicle, to the regret of many persons, suddenly lost its identity last week. As Byron had it:—

'Where is my child?'"—And Echo answers "Where?"

BRITANNIA TO AMERICA

ON THE SINKING OF THE LUSITANIA.

On butcher's work of which the waste lands reek;

Now, in God's name, from Whom your greatness flows,

Sister, will you not speak?

Cleanliness is next to Godliness.

From a Parish Magazine:—

"Many thanks to the Revs. ———, ———, and ———, for their help on the Sunday after Easter, during the spring cleaning of the Priest-in-Charge."

FOR HOME AND BEAUTY.

Against a bodiless foe,

Merry of heart and moist of pore

By Kingston Vale they go;

Gaily they swing, this eve of May,

Between the blossoms blown,

Column of route, in russet grey,

The Veteran "Devil's Own.'

Churning the tar and heat,

And throw a dull and curious eye

On men that use their feet—

On men that march in thirsty ranks,

Poor hopeless imbeciles,

When all but beggars, dogs and cranks

Career on rubber wheels?

Home from the course they ride

From keeping up the noble trade

That swells the nation's pride;

For these our Army does its bit

While they in turn peruse

Death's honour-roll (should time permit)

After the Betting News.

Should humble soldiers give?

Why even we, mere Inns of Court,

Who pay for leave to live

If William ever cross the wave,

Into the fight we'd spring,

And at our own expenses save

The Manhood of the Ring.

O. S.

UNWRITTEN LETTERS TO THE KAISER.

No. XXI.

(From Captain Helmut von Eisenstamm, at present confined in an Officers' Prison Camp in England.)

All Highest War Lord,—I trust your Majesty will not misinterpret my true feelings of devotion to your own person and to the cause of our Fatherland if, humble as I am, I venture to address these few lines to you. I am a prisoner of war, removed now for these many weeks both from the opportunity of serving my country and from the chance of incurring death or wounds on its behalf. We who are here are not unreasonably restrained. There is, of course, barbed wire, and there are many sentries, as is only natural; but we are allowed to arrange for ourselves such amusements as we can devise, both indoors and in the free air. We play at football, we have concerts and dramatic representations, we lecture to one another on subjects of interest, and the vigilance of those who guard us, though it is to the highest point careful, is never willingly oppressive. The food is good and plentiful. In short, I may say that we are treated with the consideration which is due from brave men to those who by bad luck have fallen into their hands.

That is the case not less with the German private soldiers who are permitted to wait upon us than with the naval and military officers, to the number of more than a hundred and fifty, who are confined here. The house is large and there are many rooms; the garden and the walks are in the simple English style; and when we go walking there we are not shut in by dark and frowning walls, but can look out over the pleasant country which lies beyond. The Commandant and his officers are not tyrants to us. Everything, indeed, is done to make our lot as tolerable to us as the hard circumstances permit. I have in my time said many harsh things of the English (and some of them are perhaps still true), but that they know how to treat misfortune without severity and how to behave as gentlemen—I use the English word—to enemies who are harmless and in distress, this I shall always henceforth affirm to the best of my ability in the face of those who in ignorance presume to deny it. Like Luther, here I stand; I cannot otherwise. I am sure it will give pleasure to your Majesty to hear that this is so, for you are the father of your people, and it would grieve your paternal heart if it were proved that anywhere even the least of your subjects was suffering under wrong or cruelty. Of these there is not, and never has been, the smallest trace.

Yet even with all possible mitigations how wretched is the fate of one who is a prisoner. He is in a foreign land, and is commanded by those who are foreigners and speak in a foreign tongue. He thinks of his own dear country and of those he loves. It is true that he might be dead had he not been taken, and that he would never have seen them again, whereas now he is in no danger; but this cannot console him. Somehow, indeed, it seems to him to be an aggravation of his lot, for he has not even the freedom now to offer his life. To add to the misfortunes and sufferings of such a man by unnecessary harshness or cruelty would be an inhuman wickedness, and it is impossible to conceive that any civilised nation could do this thing. To be sure it is stated in English newspapers which we are permitted to read (I do not find the permission a very valuable one) that English prisoners in Germany have been shamefully dealt with. It is said that they have been hooted and spat upon, that they were herded together in cattle-trucks filled with filth, and that in their prisons they are scarcely treated as human beings. Such charges I should look upon as necessarily untrue, but I know that war corrupts human nature in some miserable men, and I appeal to your Majesty, if there has anywhere been such conduct, to stamp upon it and punish it. You are all-powerful, and you have but to say the word. It would be a terrible thing for us Germans if, when the War is over, our soldiers dare not look one another in the face with frank honour because some scoundrels have wreaked their malice on unfortunate Englishmen, and have incurred no penalty for such a crime.

With inmost loyalty, von Eisenstamm.

TO THE POWERS OF DARKNESS.

And chuckle at our human thirst for facts,

How long will ye hermetically bottle

The stirring tale of Tommy's glorious acts?

Be warned in time, lest all too late ye learn

The Lion, even as the worm, will turn!

By Teuton war-lords o'er the list'ning earth,

No longer by our sheets is relegated

To niches sacred to the god of mirth;

Those once-derided "facts' we now are shown

In strong and startling type beside our own!

And deeming that the dizziest of views

Are better, after all, than total blindness,

Should simply boycott you, and read no news

Unless it clearly shows itself to be

Made, or at least inspired, in Germany!

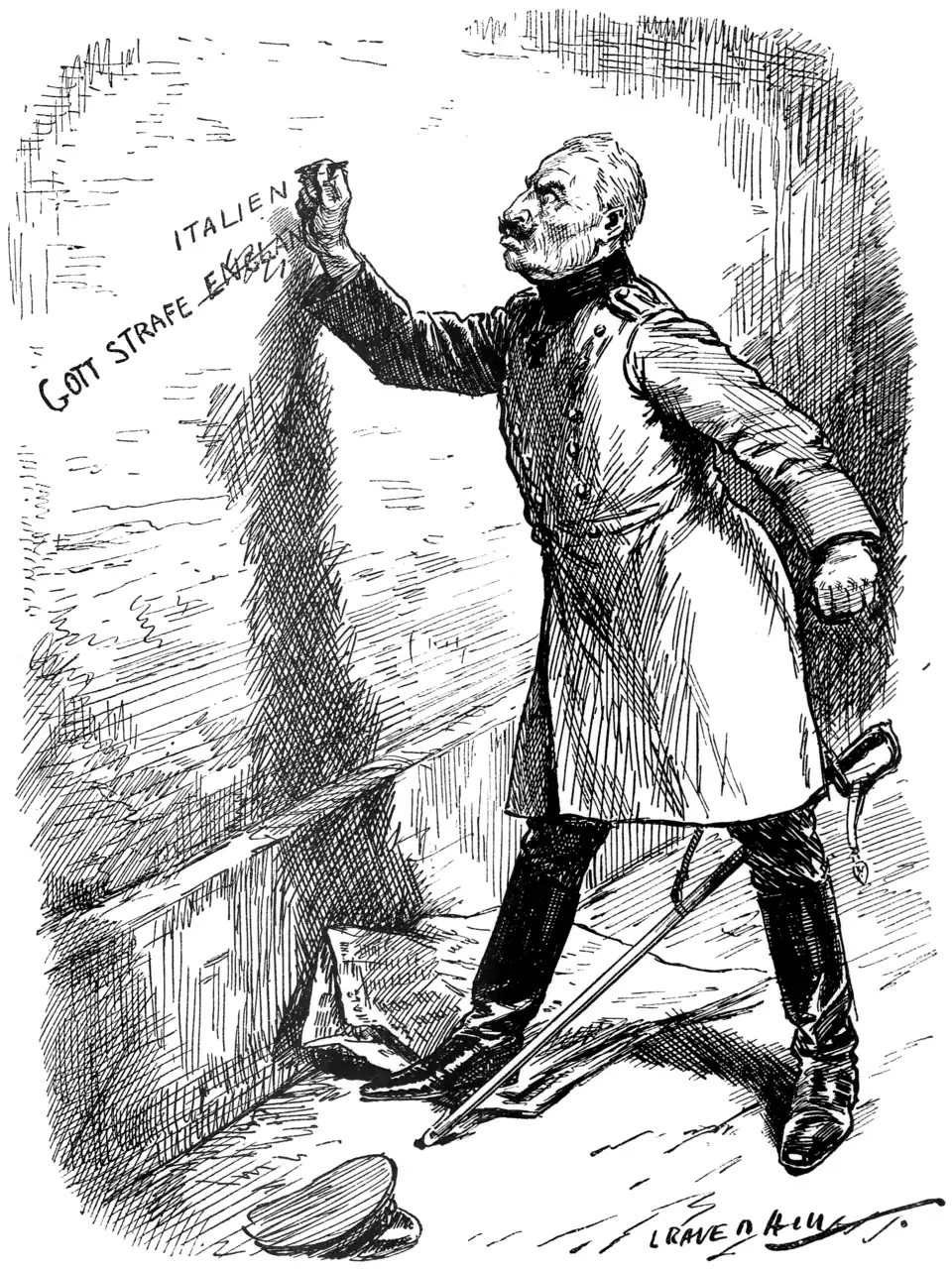

ON WITH THE NEW HATE.

GIVEN AWAY.

Bored Officer (after reluctant visit). "Good-bye, Mrs. Jackson—enjoyed myself immensely."

Wife. "There—I told you so! I knew you'd enjoy yourself."

A TRAMP JUGGLER.

"Talking of tramp-jugglers," said I, if you would like to hear about a turn I saw the other day———"

"Go on," said the others.

"Well, he wandered on aimlessly at first, dragging a toy horse with a very stumpy tail and talking to himself. 'La, la, la,' he said. Then he went and leaned against a sofa in a most gallant attitude and talked to a lady friend. 'La, la, la' was still the burden of his talk. He didn't seem to notice that his legs were slipping from under him. Just as he was collapsing he grabbed at the lady's nose and the horse's tail, and came down in a glorious tangle."

"I know," said Lionel, chuckling.

"In the midst of the tangle he found a brightly-coloured picture-book and began reading it with a casual air. Then be threw the book away and fell over the horse on to a box of wooden bricks. He played with them lying flat on the ground. Then he stood up with one foot among the horse's legs and the other in the brick-box."

"Go on," said Lionel.

"He wandered off and returned in a second or two carrying a towel and a sponge and licking a piece of soap with evident enjoyment. He tripped over the towel and fell flat on his face still clinging to the sponge and licking the soap imperturbably. He opened a chocolate box lying on the floor, took out a chocolate, ate it and put the soap in its place. Then he scrubbed the floor with the sponge and rubbed it with the towel. He tried to put the sponge in the chocolate box. It wouldn't go in. He threw out all the chocolates, gave another lick to the soap, put the sponge in the box, tried to rattle it and threw it away."

"I can see it," cried Lionel, in ecstasy, "I can see it exactly."

"Once more he wandered off, first stumbling over the horse, and falling flat on the towel, and came back with two balls. He threw them on the floor. Then he brought two more. Then he brought a hair-brush. He brushed his hair the wrong way. He brushed his clothes. He put out his tongue, brushed that, and didn't like it. Then he picked up a ball and brushed its hair. Finally he used the brush to sweep the floor."

"After that he went round and slowly gathered the balls. Usually when he had got three he stumbled over the horse or the towel. He tried to make the horse eat one ball and he tried to put one in the chocolate box. Then he washed them with the sponge. At last he stood with all the four balls in his arms. And then———"

"And then," said Lionel, "there was some first-rate juggling. By Jove, I must see him for myself. Where is he on?"

"We shall always be pleased to see you," said I, "and I have no doubt you will enjoy an average ten minutes of the life of my first-born, aged sixteen months."

"The co-operation between the Fleet and the Navy was excellent."—The Scotsman.

Our contemporary does not mention it, but we hear on the highest authority that the Troops and the Army also worked together most harmoniously.

"General James Drain, of Washington, has wired to General Hughes, Minister of Militia:—'I glory in the magnificent brewery of the Canadians.'"—Wolverhampton Express and Star.

The Chancellor of the Exchequer is said to regret the wording of this tribute, as being calculated to prejudice the success of his attempt to cope with the drink question.

"But I understood from my wife that you were leaving us to marry the sweep."

"Yes. But if it's all the same to you, Sir, I've changed my mind. 'E's been and joined the Bantams; an' wen I sor 'im wiv 'is face washed———!"

A TERRITORIAL IN INDIA.

VII.

My dear Mr. Punch,—We have completed the dreaded Kitchener Test, and found it not so very terrible after all. In fact, strictly between ourselves, we quite enjoyed it, though naturally in our letters home we endeavour by subtle suggestion to convey the impression that we have had the very deuce of a time.

Our first ordeal was to rise at 4 A.M. and do a fifteen-mile route march, followed by a spirited attack upon the barracks. Roman Catholics were exempt from this test. It was a Saint's day, and they rose three hours later than we, enjoyed a leisurely breakfast and attended church. You might not believe me if I told you the number of converts to their religion from our battalion since then.

In this attack we used no ammunition, and the bursts of firing which covered our sectional rushes were represented by a vigorous working of bolts and easing of springs. Having proved that we could perform this operation without undue danger to ourselves and the public, we were provided with blank cartridge for the strenuous rearguard action which we fought on the following day. Again there were no casualties beyond the collapse, under the terse eloquence of our Colonel, of one unfortunate, who chanced to let off his rifle at the wrong moment. Though still very weak, he is expected to recover.

Shortly afterwards we waged a desperate battle against a strong force of cunningly entrenched cardboard heads and shoulders and canvas screens, and this time—so impressed were the authorities by our previous successes—we were permitted to use ball ammunition. Incredible as it may seem, we again came through unscathed, but the enemy was shockingly mangled.

You must not suppose that these exercises comprised all the Kitchener Test. We marched out by night across country to take up a position against a theoretically hostile village in such absolute silence that one officer was afterwards heard to declare that the rustling of a cricket's eyelashes as it blinked was distinctly audible to him. Then there was an affair of outposts and other searching examinations of our military knowledge and prowess with which I will not weary you.

It is a good thing the Test is over, because the weather is getting indecently hot. But it is the growing plague of flies and mosquitoes which threatens to render life unendurable. With regard to the last-named, I have recently been told of an infallible method of escaping their attentions at night. All you have to do, states my informant, is to leave a gap in the mosquito curtain round your bed ten minutes before retiring to rest. All the mosquitoes in the room will eagerly swarm through it. Then you merely close the aperture and sleep in peace on the floor while the baffled insects fight against one another in their prison.

I feel sure it is an admirable plan, but unhappily we have no mosquito curtains.

Though the perspiration we now shed would seem to be the limit, we have yet, it appears, to learn what heat really is. The knowledge will not long be withheld from two hundred of us, who are under orders to leave in about a fortnight for what we are assured is the torridest and unhealthiest hot-weather station in all India. Our Commanding Officer did his best, when giving out the announcement on parade, to hearten us by stating that flowers are very cheap there, and that he himself is quite competent to read the Burial Service over us (Cheers). He added that the only duties which the survivors will be called upon to perform will be to do guards and sleep. If promotion should result from proficiency at the latter, you may expect to see me coming home at least a sergeant.

For myself, I shall pin my faith to Zeem Soap, sold in the bazaars here. A leaflet describing this miraculous preparation was thrust into my hands a few days ago at the Nauchandi Fair. Zeem Soap, I gather, is "not only indispensaple for famalies who process its beneficial effects, but removes all pimples, blouches and sorce instantaniously and requires no recommandation to cure and route out all germicide diseases." Furthermore, "health and beauty go hand in hand by its use." Health I have in abundance up to the present, but beauty will be a new and strange gift. I wonder... but I must wait in patience.

I intended to tell you about the far-famed and wonderful Nauchandi Fair, where I spent several fascinating hours, but towards the end of my visit a large notice showed me that my labour would be superfluous. The Fair was, I learned, under the patronage of—among other distinguished people—the Maharajah of Punch. Salaam, Maharajah!

You may be interested to know that some of our fellows have discovered who writes these letters to you. A few days ago I innocently overheard a conversation relating to the identity of the "silly ass who puts that stuff in Punch."

"I believe it's somebody in this battalion," said one.

"I know very well who it is," replied another. "I don't know his name, but he's a cow-faced idiot, clean-shaven—wet sort of fool altogether."

So they had found me out. The secret was no longer a secret... but what was this?

"Always hanging about the library," added the speaker. "Wears glasses."

I breathed again. I have the eye of a hawk.

Yours ever, One of the Punch Brigade.

State Help for Industries.

"According to an official report, 2,000 German soldiers in Alsace-Lorraine have been decorated with the Iron Cross.

"Germany's iron ore production in March amounted to 993,438 tons, against 803,623 tons in February. It is steadily increasing."

German Wireless.

First Belle. "Yah! I wouldn't walk out with a kid like that."

Second Belle. "Well, he's got a uniform, anyhow."

THE WORLD'S LOSS.

And is old Bunny dead? Alas that that vast mobile countenance should never again be the battlefield of the emotions—fear, triumph, surprise, mortification, glee, despair. But so has it been decreed, and John Bunny, the hero of countless cinema comedies, is no more, cut down in his prime. For years he had been the favourite big funny-man of "the pictures," and though he has left countless imitators there is no successor, while his greatest rival in publicity and popularity, Max Linder, the reckless and debonair, fights for France.

Of all the unexpected developments which have followed the invention of animated photography none can be more astonishing than its bearing upon the late leviathan "featurer." What Bunny was doing when Muybridge, or Edison, or whoever it was, hit upon the discovery, I do not know, but one thing is certain, and that is that he was obscure; and (so little do we know our luck) a probability is that he was not without the wish, now and then, that Heaven had been less lavish to him in the matter of facial opulence. However, the cinema was born, and every day from that moment, although neither the cinema nor Bunny was aware of it, they were drawing nearer and nearer together, and his abounding face was more and more in danger of becoming his fortune. See how Fate works! And at last, one day, the two converging lines met. The god out of the machine, in the person of an alert cinema impresario, caught sight of Bunny; a thousand possibilities rushed through his mind; the bargain was struck, and Bunny started out on the great and wholly uncontemplated task of growing wealthy beyond the dreams of avarice, if ever he had any, and becoming the best known man in the world.

For that is what he was! Helen's face may have launched a thousand ships, but Bunny's enraptured millions of audiences. Wherever a picture-palace exists, whether at Helsingfors or Brindisi, Cairo or Cape Coast Castle, Vladivostok or Littlehampton, Hobart or Duluth, Bahia Blanca or Archangel, there the features of John Bunny are as familiar as household words. Vast multitudes of human beings who do not yet know what the Kaiser looks like are intimate with Bunny's every expression.

Peace to his ashes!

LISSUE.

[My wife asks me what Lissue handkerchiefs are. I am sorry to say my answer did not satisfy her.]

Along the flaming edge where sunsets die,

Holy and virginal and white as milk

Royal princesses spin the costly silk,

The gleaming tissue

Of far-famed Lissue.

Mile after mile the Lissue gardens run;

Tall pale princesses, with their flaxen hair

Circled with crowns of gold, are spinning there

Hanky and fichu

Of filmy Lissue.

And royal ladies stifle a last yawn,

Perhaps they hear when fall the winter rains

An eerie sound across the mist-bound plains,

A ghostly "tish-oo!"

Smothered in Lissue.

AN ANGLO-BELGIAN VENUS.

"We are going to have three," announced my cousin as I sat down beside the tea-table.

Cynthia has a habit, which occasionally makes her a little difficult to follow, of picking up by a very small thread some conversation of the week before last.

"Bravo!" I said, hoping for further light.

"You see, it was a question of bedrooms," she continued.

"In all these cases," I agreed, "it is the bedrooms that really count—that is, I should say, it is the bedrooms that have to be counted."

"Cynthia feels with me that what is imperatively needed in this—ahs—omewhat remote district is a practical example," said my Uncle James from the fireplace.

Uncle James is generally to be found near the fireplace. He is a man for whom I have the greatest respect. A rural dean in rather a large way, with an apostolic manner faintly diluted at times by a decorous bonhomie, he may certainly be regarded as one of the stouter pillars of our local society. His remark, however, though embodying a sound ethical principle, did not seem to get us much farther forward.

"I shall have to rub up my French," said Cynthia.

At last I understood. "Pas du tout," I said politely.

"What?" asked Uncle James in a slightly puzzled voice.

"Je ne voulais que dire," I replied with some difficulty, "que mademoiselle votre fille parle déjà assez couramment la langue de nos Alliés."

With the gravest dignity Uncle James finished his cup of tea and took out his watch.

"I must be going," he said; "the Archdeacon is expecting me at 5.30."

"Poor Papa!" said Cynthia as the door closed behind him; "I do hope our Belgians will be able to speak English."

About a week later I received a note from Cynthia asking me to come round in the afternoon. I obeyed, and found her looking distinctly worried.

"Où sont vos amis?" I asked.

"You needn't bother. Monsieur speaks English quite well and translates everything to his wife and daughter. Papa likes them immensely. He has taken them out for a walk."

"Capital! Then you've all settled down comfortably together?"

"I thought so till this morning," said Cynthia with a sigh.

"Qu'est-ce que vous—I mean, what's the matter?"

"It is Monsieur. You know Papa's Venus, the statuette he bought last year in Brussels?"

"Yes, I was with him at the time."

"Monsieur noticed it yesterday in the hall, and this morning he came to me and said that he and his family must leave us."

"But I had no idea that the Latin races———"

"It isn't that. It appears that he was the proprietor of the shop where Papa bought it, and that he sold it to him as a genuine antique, whereas in reality it was made in Birmingham."

"Ah!" I said sadly.

"Monsieur is overwhelmed with remorse and declares it is impossible longer to accept the hospitality of one whom he has betrayed. However, I begged him to wait at any rate till tomorrow before he said anything to Papa about it. And then I sent for you at once. So now what is to be done?"

I stared very hard at the carpet for five minutes. "Cynthia," I said at length, "your father must be sacrificed, but it shall be a painless operation—in fact, he will never realise that it has taken place."

"Are you sure?" she asked doubtfully.

"Perfectly," I said; "leave it to me."

A little later Uncle James and his guests returned, and we all took tea together. Conversation with Madame and Mademoiselle was carried on, as Cynthia had said, through the medium of Monsieur. I myself made no attempt to reach them by the more direct route, since my French, though perfect in its way, is not of the sudden, unpremeditated type so much in vogue in Continental circles. After tea I managed to secure a few minutes alone with Monsieur.

I decided to come straight to the point. "Monsieur," I said, "my cousin has told me all."

"Behold," he replied, "an angel! Mademoiselle would forgive. To her it is a bagatelle. She—how say you?—she snaps at it the thumb. But for me, Monsieur, I am desolated. The business is the business; I know it. But to have betrayed one's host, it is other thing. It is impossible that I rest here."

"My dear Sir," I said soothingly, "do not distress yourself. I was with my uncle when he bought the Venus. He paid you with a 100-franc note."

"It is true," he admitted with an ineffable gesture of despair.

"Did you pass it on?" I asked.

"But naturally."

You were indeed fortunate."

"What mean you?"

"Monsieur," I said, "on the morning of our departure from your beautiful city we discovered that one of you countrymen had deceived us."

"The note!" exclaimed Monsieur "it was then a bad?"

"Alas! yes. On the previous after noon I had gone to the races, unaccompanied by my uncle, who as a ecclesiastic of the middle degree doe not permit himself such distractions On my return I was able to settle a little debt that I owed him with a 100 franc note. Next morning, when he paid his hotel bill, he offered this to the manager. The manager, who had once been a Scotchman, rejected it. My uncle was annoyed. He asked me to take hack the note and to give him another in exchange. But I also had just paid my bill—a larger one than had looked for—and had little more than my return ticket left. My uncle thought deeply. Finally he said to me "This is an unfortunate business, but it may well be that not all the inhabitants are so fastidious as the unpleasant manager of our hotel. Let us endeavour to rid ourselves elsewhere of this pestilent note. It will be but just, since what is sauce for the goose is sauce also for the gander."

"I comprehend. Then it was who?———"

"You were the gander," I said.

He smiled. "Yet at the end not I but another." I nodded.

"Monsieur," he said happily, "you have raised the weight from my soul It is what you call allsquare."

ON A RECENT VICTORY.

Failed to convince me of the German win:

But now that Wolff's Bureau discounts the haul,

There may be something in it, after all.

Clerical Resilience.

"They had had the B hop of Buckingham among them, and he was sure they would wish him to greet him under his new title and say how greatly they looked forward to an increase of spiritual activity in the Church owing to his appointment."

Report of Oxford Diocesan Conference.

Where the B hops, there hop I.

"Distance Lends Enchantment."

"PORTMAN-SQUARE (two miles from it).—Very bright Furnished ROOMS on second and third floor, bath, electric light; references."

Advertisement in "The Times."

This apparent prejudice against Portman Square is to us inexplicable. We have always understood it to be quite a respectable locality.

"I see Mr. Basil be home again, Miss. I wondee if he be in the same regiment as my son. It be called 'The British Expeditionary Force'!"

PUNCH IN HAMPSTEAD.

Of gruesome placards and the cry

With which the urban newsboy charms

Odd pence from passers-by—

Through Hampstead town at eve I sped,

And sudden heard the pan-pipes' note

Sound cheerily ahead.

There came an eager urchin throng

Shouting for joy that Punch had come

With frolic, jest and song.

A respite from the current care,

Hoping that War's unhappy din

Would find no echo there.

I saw the all-pervading Hun

Disfigure each remembered scene

And spoil the homely fun.

Burlesqued von Turpitz in his lair;

Cast from his old estate, the clown

Appeared as Wilhelm's heir.

He too was changed, and though he wore

The same red flannel tongue his smile

Was sadder than of yore.

A quaint embodiment of fate,

Punch stirred the patriot reptile's rage

By calling him U 8.

Fell flat and lifeless to the ground;

With heavy heart I crept away

Before the hat came round.

THE SPORPOT.

I am not sure if that is how they spell it in Belgium, but that is how we mean to spell it in Crashie Howe. We have reason to be grateful to our refugees for introducing this admirable little implement. For the Sporpot has come to stay.

The first I heard of it was from Louis when he went to work in the Minister's garden. He made good wages there for a week or two, and the thing was rather on his conscience. He came to me to discuss the point. Should this money be paid to go against the cost of keeping his family, or should he spend it? But before I could reply a perfect compromise occurred to him. He would put it in his Sporpot. It seemed to be an excellent arrangement.

There is nothing new in principle about the Sporpot. Most of us began life with something of the sort in our possession. But it always had a key, and that was where it failed. A Sporpot with a key is no better than a ship with a leak. It must be unrelenting, imporous, adamant, without compromise or saving clause or loophole or back-door. It is the absolute cul-de-sac. Once you have dropped in your coin through the slit at the top it should be as irrevocable as yesterday. Of course the thing can be broken open, but no one would care to have any dealings with the sort of man who would break open his Sporpot. Unless, of course, he can prove it full.

As the proper emblem of a thrifty people the Sporpot seems to be quite domesticated in Belgium, as much a member of the household as the dresser or the clock. And the Belgian's first important undertaking, after he settled among us, and as soon as he had satisfied his more urgent needs—such as catching chaffinches and making cages for them and hanging them up outside the door—was to establish a Sporpot. And there could be no more fit companion for the exile. It is a slender thread that still holds him to Belgium, far away. It keeps him looking forward, for it is at least a beginning—all he can do in these long months of waiting. Like the little tag-end of Belgian soil that is still defended by the Allied Army, it is at least a jumping-off place for the New Start.

May every Sporpot be full (and ripe for the hatchet) on the Day!

Moather (whose husband has lately joined the Territorials). "Do you know, darling, Daddy is a soldier now?"

Child. "Oh! mummy. Then will he come up to the pram and say, 'Hello, baby, and how's Nanny?'"

WHY HENERY WENT.

Henery—for that was what everyone called him—was the despair of the village recruiters. Everyone tried to induce him to enlist and everyone failed ignominiously. The Vicar, who had conceived the totally erroneous idea that Henery had conscientious objections to fighting, proved to him that fighting in a cause like ours was clearly justified by all laws human and divine.

"Don't you go 'pologisin' to me for goin', Sir," said Henery. "I'd never think o' blamin' you, Sir. I minds my own business."

The postmistress, greatly daring, presented him with a white feather.

"Thankee, Miss," said Henery, putting it in his hat, "but I tells you if you goes chasin' Squire's ducks to give young men presents you'll get into trouble."

The Squire himself told Henery that every young man who could shoulder a gun ought to be off.

"It's none o' my business, Sir," said Henery.

"Is there a coward in this village?" demanded the Squire.

"Your gamekeepers don't think so if they swore true at petty sessions," replied Henery.

And certainly it was a fact that Henery on one splendid occasion had tackled three gamekeepers and thrashed them horribly.

Not even the news that his stepbrother Albert had been taken prisoner moved Henery.

"Why should I go botherin' about 'im bein' in prison! 'E never went and fought no one when I was doin' three weeks instead o' paying five pound and costs."

Even Mr. Bates of "The Bull" used his potent influence in vain. "Look 'ere, Henery, just you see what these Uns have been up to."

"They never done nothing to me," persisted Henery.

But one morning the postman handed Henery a postcard over the garden hedge.

Henery read the postcard with difficulty, put his spade in an outhouse, took down his old hat with the white feather in it and walked straight to the railway station.

"Where are you goin', Henery?" asked the station-master.

"Off to 'list. Look at that postcard."

The station-master read "Thanks for fags. Why didn't you send something to eat? Hoping this finds you well as it leaves me at present. Albert."

"I sent 'im a pork-pie with them fags," said Henery. "'E was always a wunner for pork-pie. Well, they pinched it. Now I minds my business, but folks as interferes with me gets sorry. I'll make that Keeser sorry 'e touched my pork-pie."

And leaping into the train, and waving the white-feathered hat in farewell, Henery departed into the unknown.

Branding a Butterfly.

"The butterflies of this month are very few, apart from the second-hand hibernators from last year. The green hairstreak is a surprise without a rival. Who could see an apple-green butterfly without marking it with a red lotter?"—Daily News.

This branding of butterflies, even if they are second-hand, ought to be stopped.

A CHEERFUL GIVER.

ESSENCE OF PARLIAMENT.

(Extracted from the Diary of Toby, M.P.)

House of Commons, Tuesday, 4th of May.—Imperturbability of House of Commons amazing. Twelve months it listened to exposition of a Budget which estimated an expenditure of £197,493,000, and counted upon a pleasing surplus of three-quarters of a million. After a period of eight months of War it learns that at end of financial year expenditure has run up to £560,474,000, leaving Chancellor of Exchequer faced by deficit of £333,780,000. Hears this startling story with as little sign of emotion as was displayed when it listened to the earlier one. It did not blench when the Chancellor incidentally mentioned that average daily cost of the War now amounts to £2,100,000. If it ends in September the aggregate would reach £786,778,000. If it runs on to April next it would exceed eleven hundred millions sterling!

David (to the Philistine): "Look here, old man. I should hate to be the cause of any unpleasantness. Why not approach me as a deputation and talk things over?"

This stupendous sum, never before mentioned by matter-of-fact Chancellor of Exchequer, seems more appropriate to the Budget of Wonderland. House this afternoon quietly recognised it as an actuality that must be faced. Resolved that, at whatever personal sacrifice, money must be provided.

Attendance, though full, not comparable with number accustomed to gather on ordinary Budget nights. Apart from absence of Members on active service, House just now fed up with Budgets. Time was when we had them once a year. Once a quarter is now nearer the mark. Last November one presented in supplement of the customary spring cleaning of the Exchequer. Another last week in connection with Drink Duties. And to-day "Here we are again," as the Chancellor of Exchequer might say, were he in merry mood. Nor is this all. There is promise of another within six months when, as Chancellor puts it, we shall be in better position to judge of duration of War.

A sprinkling of Members faced him from side gallery. They might, had they pleased, have found seats below. A few Peers dropped in. In the Distinguished Strangers' Gallery Ranji looked on with the judicial air of an umpire at Lord's. When Chancellor mentioned cost of eight months' War he murmured, "What a score! £560,474,000 and not out—of the wood yet."

1914 Peace Budget. The Fighting Cocks.

1915 War Budget. The Love Birds.

Throughout exposition, brief for such occasion, there was little of the laughter or cheering that usually punctuates a Budget speech. Exception made when, in opening sentence, Chancellor remarked that "the operations of the coming Summer will alone enable us to form a dependable opinion-not as to the ultimate issue of the War, because that is not in doubt—but as to its duration."

Sharing this conviction of certain if delayed victory House not disposed to waste time in talk. By ten minutes to nine formal Resolution passed without division, practically without criticism.

Business done.—Budget introduced.

Wednesday.—In both Houses talk of treatment of thirty-nine British prisoners in Germany, carefully selected in order to have practised upon them reprisals for alleged ill-treatment of officers and crew of German submarines guilty of murderous practices on the high seas and interned in this country. In the Lords the Earl of Albemarle broached the subject. Profound sympathy manifested towards him by those who knew that one of the victims of German insensate hate is his son. In the Commons Lord Robert Cecil, on motion for adjournment, questioned Premier.

Squalid story simply told in letters from the victims read by both noble Lords. One, dated April 13th, and written from a convict prison, tells how "we are locked in cells 12 feet by 6 feet [just the size of a billiard-table]. We are not allowed to speak to each other. A bowl with a little coffee in it forms our breakfast, and a mixture of potatoes and meat our lunch. At 2.45 we walk in a tiny little yard, about 20 yards long, for about three-quarters of an hour."

Difficulty of dealing with the matter obvious. If the jailers of these gallant fellows were Red Indians or Zulus they might be made amenable to dictates of common humanity. But, as Premier said, "maltreatment of prisoners of war, a form of cruelty common not even in the Dark Ages, has been left, as many other fiendish devices in this great War have been left, to one of the Christian nations of Europe to invent and elaborate."

He repeated assurance that note is made and record carefully kept, with view to meting out at conclusion of the War due punishment

to the men responsible for these barbarities.

Meanwhile the victims suffer solitary confinement in narrow cells, eat their scanty allowance of meagre food, take their strictly limited daily exercise in the backyard, and are left without light or heat when darkness falls. This is avowedly done by way of avenging similar ill-treatment alleged to be dealt out to crews of German submarines. This fable Under Secretary for Foreign Affairs disposed of in a sentence.

"The only difference," he said, "in the treatment of German prisoners is that the officers and crews of the submarines are put in a camp by themselves."

Business done.—Vote for Agriculture and Fisheries agreed to.

Thursday.—Prime Minister gave graphic account of operations in the Dardanelles. Extolled unsurpassed courage and skill of troops engaged in difficult operations of landing on open beach in face of determined opposition.

House noted with satisfaction that he avoided practice in similar circumstances prevalent elsewhere, suggestive of the wary ostrich burying its head in the sand, with its toes scratching on surface and throwing up asterisks, blanks and dashes cunningly devised to mislead the enemy.

Premier detailed the divisions engaged, and gave names of Commanding Officers. As to locality he scornede reference to "Somewhere in the Near East," and specifically mentioned Gaba Tepe, Sedd-ul-Bahr, and Kum Kale.

Effect of this novel departure will be closely watched. If no harm comes of it, it may be adopted elsewhere.

Chancellor of the Echequer proposed to take Second Reading of Bill amending Defence of Realm Act. As it involves question of increased taxation on Spirits Irish Members up in arms. Eventually arranged that House shall meet specially on Monday, when Chancellor hopes to have come to understanding with the Trade.

Last Sunday the devotions of citizens of Dover disturbed by appearance of aeroplane approaching from the sea. Visions of the fate of dwellers in the Eastern Counties appalled them. To their relief, after brief survey of the town aerial visitor made off in direction of Folkestone, where similar excitement temporarily prevailed. Again the airship contented itself with harmlessly fluttering "o'er the Downs" and passed away into space.

Conjecture rife as to its identity and purpose. That it belonged to the enemy and was out for no good were matters upon which Dover and Folkestone were firmly agreed.

Privily stated in House to-night that the airman was no other than Cousin Hugh. Well known he has of late, with that concentration of purpose that makes him a potent factor in politics, taken to aviation. This happened to be his Sunday out, and in the course of his flight it is rumoured that he chanced to pass over these Channel ports, unaware of the consternation he created.

Business done.—House adjourns till Monday instead of Tuesday.

Some of Susie's sisters sewing sand-bags.

The Roll of Honour.

'Mr. Punch hears with deep regret that one of his artists of former days, Mr. J. L. C. Booth, Lieutenant in the 12th Australian Infantry, has been killed in action in the Dardanelles.

Fond Mother. "I'm afraid it's no use; he's set his mind on having one with 'Jellicoe' on it."

AT THE FRONT.

There is a delusion current that this war out here is stationary when it does not move. It is true that there was once a rumour that certain lines of trenches came to understandings with certain other lines, by which blue and red flags were waved before the occupants on either side fired off rifles, or committed similar dangerous acts which might otherwise have been interpreted as unfriendly. In the meantime they completed the tessellation of their pavements and installed geysers and electric light. Everyone has heard the rumour, but no one you meet was actually there; so the only conclusion we can come to is that both sides dug and dug until they got completely lost underground, and were either incapable of return, or so happy, comfortable and well found that they stayed there, thus ingeniously leaving the war without leaving their posts, which is, after all, the ultimate ideal of troglodytic patriotism.

However that may have been, the war elsewhere is in a state of steady evolution. You can never count on it. You get into a beautiful quiet trench, the sun shines and the birds sing, and you plant primroses on the parapet, and arrange garden parties, and write home and ask the sister of your friend to come out and have tea in the trench on Friday. And then on Friday, just as you're getting the tea-things out, and sorting the tinned cucumber sandwiches, and shifting the truffles out of the pâté, the wind blows from the north, and the rain rains, and the birds shut up, and an 8-inch shell comes crump on the primrose bed, and stray splinters carry away the teapot and the provision box and the cook; and on the whole you're not sorry Leonore couldn't come after all.

Not long ago it seemed good to the état majeur that no officer should be in possession of the means of supplying the pictorial daily with pictorial war. Every company in every regiment duly rendered a certificate that it was without cameras. Now there was a certain regiment much given to photographic studies. And when the day came that the certificate should be signed and rendered, the commander of A company bethought him of his old-time friendship with the commander of B company; and in token of his sincere esteem sent to him as a gift the three cameras which his officers had no further use for. This done, he forwarded his certificate. B company, though delighted at the gift and the spirit in which it was offered, had already four cameras in possession of its officers. Moreover, the time for B company to render its certificate was at hand. And seeing that there was much friendship subsisting between B and C companies the O.C. B company remembered that the O.C. C company was a keen photographer, and one likely to welcome a gift of seven cameras. Having despatched them, he signed and certified for B company. C company, whose gratitude cannot easily be described, was nevertheless in an obvious predicament. So, when C company certified, D company was in possession of thirteen cameras; and finding that A company had now no cameras at all rendered unto it the very large stock with which it was reluctantly obliged to part, and unto the C.O. a certificate that D company was cameraless; and the C.O. certified in accordance with company notifications.

That evening company commanders dined together, and latest advices advise that the wicked regiment still spends its spare time in photographing approaching shells, devastated churches and Tommy at his ablutions.

AT THE PLAY.

"The Kiss Cure."

Those who imagined that the Liverpool Commonwealth Company were to reproduce for us the grim and dour actualities of a Lancashire interior in the manner of the late Mr. Stanley Houghton and the Manchester School, were doomed to be disappointed. Apart from the Irish butler and the Scotch cyclist, there is very little in The Kiss Cure that might not have been just as well conveyed to us by any London playwright and company who had studied the manners of our Tooting minxes and our Surbiton bloods. Still, since even these types may have in them a touch of novelty for certain sections of a London audience, we had something to learn. Thus we came to know that there are minxes by habit and experience and minxes of occasion; and the same with bloods. There are those who practise indiscriminate kissing as a test of the emotions, and employ the art of jealousy as part of the daily routine of what they call flirtation; while others, not among the mystics, allow themselves to be temporarily initiated into these rules for single and serious ends, and make a sad mess of it. All this may be very suburban, but when the actors' hearts, as here, are in it, you can, with a little goodwill, be sufficiently amused. And anyhow, after a course of stage problems and intrigues, the whole thing looks as innocent as the habit of ice-cream and claret-cup.

The company played well together. Miss Winwood was a practised minx, though her artfulness did not extend to her gestures, which suffered from angularity. Mr. Armstrong, as a Scotchman with a stutter, who knew the rules of the game, and Mr. Cooper, as a learner, made good fun. But the best sketch was by Mr. Shine as the Irish butler. He said little, but you could see him thinking a lot. And I am glad to believe that his opinion of the society in which he found himself was much the same as mine.

Pauline, a dialogue by the same author, Mr. Ronald Jeans, preceded The Kiss Cure. It is slightly, but only very slightly, less innocent. The lady tests her lover's devotion by alleging that she is not married to the man she lives with. Instead of feeling a passionate shock of joy at this news of her legal freedom, the gentleman takes the view that her virtue is damaged, and her value, for him, depreciated. An egoistic view, of course, but I don't blame him, though the lady did. Miss Madge McIntosh made her part seem almost probable.

"The Right to Kill."

M. le Marquis de Sevigné, aged 46, officer of cavalry and military attaché to the French Embassy at Constantinople, took no pains to disguise from us that he wanted to be a Quixote. He had no trouble with his nose (like Cyrano de Bergerac), or other physical impediment—indeed he looked very well in his French-grey tunic and vermilion breeches—but he had had no opportunity of distinguishing himself either in love or war, and he was frankly on the look-out for his chance. It was unfortunate that when it came it offered him no better scope for distinction than could be got out of the murder of a very disagreeable Englishman who was obviously better dead. It meant of course that Sevigné couldn't get a medal for his feat, nor even find any satisfaction in talking about it at large.

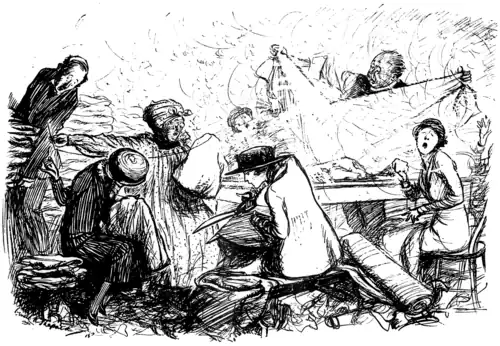

A BOSPHORUS BEDROOM SCENE.

Mr. Edmund Maurice (husband); Miss Irene Vanbrugh (wife);

Mr. Harcourt Williams (lover); Sir Herbert Tree (lady's champion).

On the other hand, it was fortunate for him that the only person who had proof of his guilt (the head of the Turkish police) was under a personal obligation to him, and so arranged to hang somebody else who wanted hanging anyhow. Fortunate, too, that the present War broke out the very morning after the murder, thus affording him a lively distraction from the embarrassment of his position, though I daresay that an ordinary domestic murder might well escape adverse comment on the shores of the Bosphorus. My only regret was that he hadn't studied the papers and seen that a war was likely to occur; for then he might have reserved himself for an occasion in which "the right to kill" was certain to be more generally recognised. And if a scrap of paper was an essential feature of his quest, he might, by waiting a few days, have killed a number of the enemy for the sake of a document that was really worth while—namely, the Belgian Treaty. As it was, in his hurry to be a hero, he had to stab a prospective Ally for the relatively vulgar purpose of securing a scrap of paper with nothing on it but a confession of frailty signed by his victim's wife. One knows these scraps of paper. Stage husbands (as in Searchlights) have a passion for them. Here the wife is forced to sign under menace of an open scandal. But how the signing of it would serve to prevent this inconvenience when the husband was in any case determined on a divorce no one knew, and no one ever will know.

The play is something better than a sordid melodrama of intrigue and murder relieved by uniforms and a cosmopolitan setting. The scene in the Pavilion is clearly designed to afford a trial of character. From his concealment in Lady Falkland's detached appartement à coucher, the Marquis involuntarily overhears a conversation which proves her not only to be unfaithful to her husband (which mattered little) but unworthy of his own devotion (which mattered a good deal). Yet the revelation leaves him unshaken in his resolve to defend her at the risk of his life.

Apart from this situation and its issues, the interest lay for us in the continued strain that Lady Falkland was called upon to endure. Forced by the brutality and infidelity of her husband (flagrant) and by a sense of friendlessness (imaginary) to seek protection in the wrong arms, her heart was torn between passion for her lover and an overwhelming sense of the deepening shadow of tragedy. She seeks relief in confession to a woman friend; and in this scene the humanity of Miss Irene Vanbrugh made irresistible appeal. More than her words, the play of her lips as she tried to wear a brave face revealed the insufferable anguish of her heart. I have seen Miss Vanbrugh in many such ordeals, but cannot remember a finer delicacy in her revelation of womanhood.

Sir Herbert Tree was the hero, suffering a little from the distraction

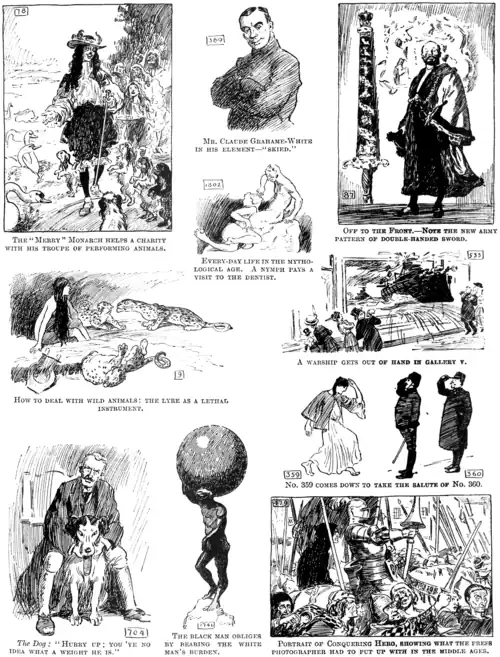

ROYAL ACADEMY—FIRST DEPRESSIONS.

of actor-management on a first night. I liked him best in his less strenuous moments. His modern uniform suited him well, much better indeed than those martial trappings of antiquity in which he has often figured. In his mufti, which showed no hint of Gallic fantasy, his moustache made him relatively commonplace, and I cannot help thinking that his murder of Falkland would have been more effective if he had done it in uniform. How he escaped general observation while entering, and debouching from, the lady's window in full view of the Bosphorus, which I understood to be packed, like Henley, with interested spectators, I shall never understand.

As Mehmed Pasha, Mr. Arthur Bourchier, disguised in an aquiline nose and a pair of eyelids which he kept lowered, like blinds, for the purpose of inscrutability, had a part that he could hardly help playing to universal admiration. Mr. Harcourt Williams, as Prince Cernuwitz, a chevalier d'industrie of the first class, might have contrived a more obvious air of villainy, but the atmosphere of diplomacy at the Sublime Porte would naturally encourage secretiveness.

Mr. Edmund Maurice's art was wasted on the unrelieved and clumsy brutality of Falkland. Miss Granville was excellent in the First Act, one of those scenes—the usual dazzling reception—where you have to find out, from momentary flashes of dialogue, who everybody is and how they got there. These scenes always make me dizzy, but the intervention of Miss Granville, as a nice woman of the world, gave me courage and confidence.

The play, on its own merits, modest but sound of their kind, goes well, and should run; though its course might have been lightened by a little more humorous relief. Whether it does justice to the original novel on which it is based is another matter. I do not attempt to institute a comparison, partly because the book is no business of the critic's, but chiefly because I haven't read it. O. S.

From the cotton report of the Liverpool Courier:—

"As the situation shows but little change from that experienced lately, we can only repeat what we said last week—that buying on conservative lines on week days will, no doubt, prove remunerative."

Our contemporary's persistent discouragement of Sunday trading does it credit.

The Question of the Hour.

To doubtful Patriots: Potstill or Potsdam—which will you have?

THE TRIPLE HANDICAP.

And rather slow for my years,

I knew a boy who in mind and mien

Outdistanced all of his peers;

His clothes were tidy, his hair was sleek,

For he brushed it morning and night;

He was equally good at Latin and Greek,

And his sums were always right.

His neatness the matron's joy;

He never did anything wrong, and yet

He wasn't a popular boy;

For his name excited a vague mistrust

And his face our prejudice fanned,

And we all of us felt a deep disgust

Whenever we shook his hand.

Tradition he never defied;

And he certainly wasn't wont to give

Offence by swagger or side;

He made no claim to be bold or brave;

He didn't hustle or shove;

But he wasn't marked for an early grave,

Like those whom the high gods love.

Bowed down with many a prize,

And four full decades had rolled away

Ere next he fronted my eyes;

'Twas down at Shrimpington-on-Sea,

Where I was taking the air,

With my daughter upon my arm, and he

Was wheeling an old Bath chair.

For taking the ball at the hop

Should sink in the depths of the struggling crowd

Instead of reaching the top?

Well, all through life he had fought with odds,

For his name was Adolphus Jopp,

He had an eye like a parboiled cod's,

And a hand like a cold pork chop.

"Save us from our friends."

"Four large transports of Germans have been sent as reinforcements to the Dardanelles.

"A big panic reigns in Constantinople."

Correspondent of "The Star."

"The Austrian Post Office has put into circulation a new series of stamps, on which are engraved the victories which Austria has obtained in the present war."—Central News.

Austria must, indeed, be chastened when she admits that all her victories could be written on the surface of a postage stamp. The back, of course, is reserved for the lickings.

"LAST MOMENTS OF THE

'KARLSRUHE.'She Strikes a Beef and is Blown Up."

Calcutta Empire.

Bully Beef

IF IT GOES ON MUCH LONGER.

If it (there is only one meaning to "it" just now—the War) goes on much longer, and England, already giddy with the Chancellor's figures, is made bankrupt—a contingency which our courage declines to contemplate—American millionaires will have the chance of acquiring the Old Country. Some such advertisements as these may then be expected:—

To Sporsmen. Great Bargain.

Suitable for rich American or Argentine gentleman thinking of taking up racing in England, the only industry that still flourishes there, unharmed by the War—Hyde Park. This famous open space, or lung of London, as it has been epigrammatically styled, would make admirable training ground for thoroughbreds, and might even be laid out by an enterprising speculator as a racecourse, thus bringing the noble sport nearer still to the Metropolis and preventing any confusion between race-trains and the trains conveying passengers intent upon their work. No reasonable offer refused.

For River Lovers.

Banks of Thames. Historic building known as the Tower of London. Replete with every romantic requirement: Traitors' gate, headsman's block, moat; unparalleled view of shipping; close to Tower Bridge; constant 'buses.

To Collectors.

Messrs. Minstrel have instructions to sell, for the benefit of the English nation, the contents of the building in Bloomsbury known as the British Museum. The sale will begin each morning at 10 o'clock, and go on for a year. Every taste catered for. The collection ranges from Elgin marbles to umbrellas left by students. Send motor lorry for catalogue. Offers invited for building. Suitable as London offices of American Trust.

Abbey for Sale!

Situate at Westminster, within easy distance of the theatres, river, Houses of Parliament and Victoria Station, old-world Abbey replete with ancient associations. Twin towers; unique historic dust; stained glass; cloisters; old-world atmosphere. The very thing for American multi-millionaires. Could be used as a cute joy-house during life and private mausoleum after death. What offers?

How we get our War-news.

"VICTORY IN GALLIPOLI.

Late Wire from Chester."The Star.

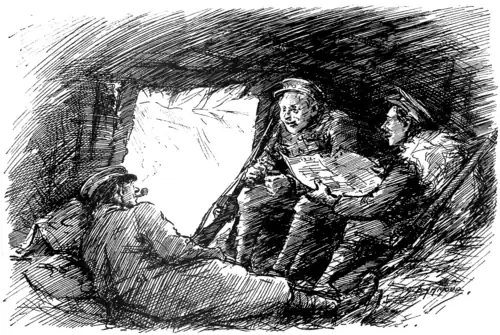

THE BUDGET AT THE FRONT.

First Tommy (reading belated news.) "Looks as if them poor beggars at 'ome may have to pay six bob a bobble for whisky."

Second Ditto. "Well, thank Heaven, we're safe out here."

OUR BOOKING-OFFICE.

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

Except that a distinguished author is entitled to have his joke like everybody else we do not quite see why Mr. H. G. Wells should have disclaimed the authorship of Boon, the Mind of the Race, etc., etc. (Unwin), in the "ambiguous introduction" he has prefixed to that work. Boon was a popular novelist, with a great vogue among American readers—Aunt Columbia he calls them collectively—and a profound contempt for the work that brought him in the dollars. The things he really wanted to write were skits upon his contemporaries, new systems of philosophy, and so forth; and here we have them in his literary remains, as prepared for publication by his friend "Reginald Bliss," a writer with whoso previous work we are regrettably unfamiliar. The whole is set forth with the assistance of subsidiary characters who act as a foil to Boon in the manner of Friendship's Garland and The New Republic. The brightness of Matthew Arnold's famous jeu d'esprit will hardly be dimmed by the new competitor, nor has Mr. Mallock much to fear from it, but the chaff of Boon's fellow-craftsmen is sometimes excellent. Occasionally it is embellished with thumb-nail sketches, the best of them being the caricature of Dr. Tomlinson Keyhole, the eminent critic who when he suspects a scandal "professes a thirsty desire to draw a veil over it as conspicuously as possible." If Mr. Wells should find himself in trouble over these indiscretions and plead ignorance, he must expect to be told that ignorance is Bliss, and Bliss is ———.

All the pleasant things that I have said in the past about the work of Mr. Henry Sydnor Harrison I should like now to repeat and underline after reading Angela's Business (Constable), which seems to me quite one of the best samples of fiction that has come to us over the Atlantic for a long tine. Perhaps it may not enjoy the widespread popularity of the same author's Queed; but there is no question of it as a book to be read. I will not tell you the story; though even if I did it wouldn't greatly matter. Briefly speaking, "Angela's Business" was to meet the demand there always is in the world for nice, normal, not too intellectual girls; more briefly still, it was to marry the first eligible man to whom these qualifications appealed with success. Angela was a home-maker. In the book we see her and her lifework through the eyes of a young man, Charles Garrott; and the argument of it is a contrast—one might almost say a competition, though unacknowledged and unconscious—between Angela's methods and those of another woman, Mary, the independent, wage-earning career-maker. Incidentally, a story of American town-life in which none of the characters is beyond the need of financial economy has a novel and refreshing effect. But there is any quantity of refreshment and novelty in the style also. Mr. Harrison has a quality in his writing that I can best catch by the epithet "sensitive." While preserving his own impartial, slightly aloof attitude towards his characters, he is quick to respond to every shade of change in their relations with each other. There is, too, a very lively and engaging wit about him. He writes American undisguised, and you may even be astonished, in your insular way, to find what a capable and vigorous medium he can make of that quaint language. Altogether Angela's Business must certainly be everyone else's also.

I begin to suspect Miss Marjorie Bowen of possessing a private time-machine, she doth so range about the centuries. Only the other day she was conducting me through Medicean Florence, and now here she is in the New World of the eighteenth century, and as much at home as if she had never written about any other place and period. Indeed, for many reasons I incline to think Mr. Washington (Methuen) is the best historical romance she has yet given us. For one thing, of course, if ever there was a hero ready-made, it is the young Virginian planter who created a nation. I am quite sure that Miss Bowen felt this. She has a palpable tenderness for her central figure, the grace and courage and high purpose of him, which greatly helps the appeal of the story. Partly this is a tale of Washington himself, first as the young soldier fighting the French in Canada, and later as the victorious founder of the American Commonwealth. Partly, also, it concerns the fortunes of Arnold, the friend who betrayed Arnold, and of his English wife. Miss Bowen has certainly written nothing more moving and dramatic than the scene in which Margaret Arnold, loathing her husband for the treachery she has just discovered, holds Washington at bay in order to give the traitor time to escape. There is a real thrill in this. Throughout, also, you will find abundant evidence of that sense of colour which is of the essence of the costume story. She writes in pictures, and excellent pictures too. I can heartily recommend this gallant tale.

Samuel Henry Jeyes; His Personality and Work (Duckworth), is a book that will have two appeals, the special and the general—of which perhaps the former will be the greater. Certainly the rather wide circle of those who numbered the late Mr. Jeyes amongst their friends will be glad to welcome this record of a singularly charming man; while there must be many others, to whom his identity as an anonymous journalist was unknown, who will here recognize work in which they had taken pleasure while ignorant of its authorship. Both Mr. Sidney Low, who contributes a sympathetic memoir of his friend, and Mr. W. P. Ker, who has arranged and edited the selections from his fugitive writings, have done their task ably. The papers themselves were well worth collection into this more permanent form. Chief among them is the series grouped under the heading "Rulers of England" open letters to prominent political personages over the signature "Friar John." These show Mr. Jeyes at his best; trenchant, entirely fearless, more than a little Thackerayan in style. Memoir furnishes an interesting opportunity of tracing the beginnings of this method in a fragment of an essay on "Sisters," written for an Uppingham journal when the author was eighteen—a somewhat remarkable production. These "Friar John" letters, it should be added, are illustrated with drawings of the addressees by Mr. Harry Furniss, which recall many pleasant memories.

The late Tom Gallon contrived to make his own wide circle of readers who will appreciate this posthumous romance, The Princess of Happy Chance (Hutchinson). It tells of Felicia of Sylvaniaburg who fled from her betrothed prince, Jocelyn, whom she chose to dislike on principle because he had been arranged for her. She fled to England, and at midnight met a young English girl of her own age, Lucidora, who was a beauty and a daydreamer. So that when Princess Felicia, with delightful impulsiveness, proposed that poor Lucidora should take her royal place with car, chauffeur and maid, she welcomed the adventure as an opening into the realms of high romance. Also an impecunious, handsome and rather nice gentleman—a journalist—foisted himself upon her as a Court Chamberlain, and the little court travelled about and behaved in the most naïve way possible, and sent the most charmingly and indiscreetly explicit telegrams, until Lucidora fell badly in love with the Chamberlain, and Jocelyn discovered she was a fraud, and explained how much he was really in love with Felicia, and everything ended happily. This is not a romance in the inspired manner of R. L. S.'s Prince Otto, or the fashion of robustious Ruritania, but just a gentle, easy-flowing, quite wholesome, unpretentious and strictly unlikely narrative to while away the time.

In those days of complex novelists I find Baroness Orczy very ingenuous and refreshing. She is indeed so anxious to impress me at the outset with certain facts about the Hungarian peasants that she repeats them again and again, and this—if a little uncomplimentary to my intelligence—does at any rate clear the way for the tale she has to tell in A Bride of the Plains (Hutchingson). What, however, I do resent is that she should address me as "stranger," for the truth of the matter is that she is the friendliest and most confiding of writers, and to be called a stranger when one feels, as I did, like a member of a family party, is nothing less than shattering. As to the literary merits of this story of love, murder, wine and dancing, I prefer to be silent, and shall hold my tongue with the greater content because I doubt if admirers of the beautiful Elsa will greatly trouble about the style in which her tale is told. Sufficient it is that the Baroness knows these Hungarians of whom she writes, that her villain is as pretty a scoundrel as I have met for many a day, and that, although the present is not a propitious time for visiting Hungary, she has induced in me a warm desire to go there eventually and see just how they dance the csárdás.

Scene: The outskirts of a Sussex Covert.

Thomas (who has bagged a sitting pheasant—as officer suddenly appears). "So you'd try to bite me, would yer?"

"Usually the annual effort is a sale of work and a concert, but in this case so as not to put too great a strain upon supporters, a concert and a sale of work have been arranged."—Exeter Express & Echo.

We ourselves always adopt this order as being far less exhausting.