Punch/Volume 148/Issue 3847

Charivaria.

Halil Bey, President of the Turkish Chamber, has informed an interviewer, "The attack on the Dardanelles leaves us cold in Constantinople." Of course our idea was that it should have a chilling effect.

⁂

"THE DARDANELLES

OPERATIONS DELAYED

By George Lyon"

Express.

It is really very handsome of Mr. Lyon to take the responsibility upon himself when everyone else was blaming the weather.

⁂

A German airman last week dropped several bombs off Deal, but failed to do any permanent damage to the sea, the holes being closed up almost immediately.

⁂

From a description of the recent raid on Calais:―"As the Zeppelin drew farther away the firing gradually diminished." This, we believe, is in accordance with the best military precepts.

⁂

A German comic paper publishes a drawing of "Admiral John Bull" surrounded by a horde of submarines, and saying, "I suddenly see rats." The German submarines, we take it, are called rats because they leave sinking ships.

⁂

The following rhapsody appeared in a recent issue of the Kölnische Zeitung:―"The German hymn 'Deutschland über Alles' is the loftiest, the noblest, the most elevating, the manliest, the most inspiring, the most tuneful, the grandest, the most poetical and glorious song that has ever welled forth from human breast. It is divine, as is the origin of the people for whom it was composed." The Kölnische Zeitung may now fairly be called a pro-German paper.

⁂

Mr. Max Pemberton has been discussing the question whether the War will hurt religion. There seems to be a general feeling that the religion of Odin will be rather badly hit.

⁂

According to the Figaro, the Kaiser has a double. This explains the popular belief that he is beside himself.

⁂

Indeed, Mr. Arnold White has recently published a book to prove that the Kaiser is mad. We gather, however, that this must be a comparatively recent affliction, for it is stated in an article in The Sunday Pictorial that His Imperial Majesty once granted an interview to Mr. White.

⁂

"£5,000 PAUPER

Investments found after Poor-Law

Funeral."

This gives one a vivid idea of the wealth of our country. German papers please note.

⁂

It is stated that, owing to the principal osier beds from which wicker canes are obtained being in Belgium, there is a marked shortage of cradles. This is serious, as children may hesitate to be born.

⁂

It is interesting to learn from the current number of The Author that there is something in the popular belief that authors write their own books and not each other's. Messrs. Methuen, our contemporary informs us, have published "Mrs. Stanley Wrench's new novel Lily Louisa, by Mrs. Stanley Wrench."

Desperate Scout. "Please, Sir, do you happen to have such a thing as a periscope about you?"

From a confectioner's handbill:―

"Meat Pies (fresh daily) a Speciality. Parties catered for and neatly executed."

Even the Germans have not gone beyond this.

A Spring Tragedy.

{{blockquote| "In the hedgerows precious primroses mildly gleamed; on the waving branches of the trees birds could be seen ready to burst. Some at least have bursted―on the elders especially."

Folkestone Herald.

This is, we fear, the regrettable result of overfeeding, and, if so, the elders (parents, we presume) have only themselves to blame for the disagreeable consequences.

Imperial Court News.

"Prince August Wilhelm recently underwent a slight throat operation at Clini Que, near Berlin. His condition is described as satisfactory."―Glasgow Evening Times.

We understand that the Prince will presently leave Clini Que, near Berlin, for the fresher air and livelier surroundings of Point d'Appui, in the North of France.

From a letter in The Edinburgh Evening Dispatch:―

"I had the pleasure of observing the beautiful meteorite on the evening of 9th March, walking eastwards.

I would see it for at least four seconds, and its velocity was somewhat slow."

Naturally, if it was walking. This case of pedestrian exercise on the part of a heavenly body is not unique. We all remember Tennyson's description of Orion, "Sloping slowly to the west."

"The 'Telegraaf' learns that one of the Prussian railway administrations recently sent a notice to all goods stations saying that the quantity of goods sent by combatants to their families at home has assumed such proportions that now and then suspicious have arisen that the packages contain illegally acquired war-booty or private property illegally seized in a hostile country, especially if the rank and social standing of the senders do not justify the supposition that the senders are men of means."

Reuter.

It was of course fully justified in the case of the Crown Prince, who is quite well off.

A Hanging Judge.

"After being suspended during St. Patrick's Day County Court Judge Drummond resumed the civil cases on Thursday."

King's County Chronicle.

"New Books.

RELIGION.

The Ideals of the Prophets: Sermons. By the late Canon S. R. Driver.

The Next Life. By the Rev. J. Reid Howatt.

Napoleon III. and the Women he Loved. By Hector Fleischmann."

The Glasgow Herald.

We should have preferred to see the last of these books classified under "Various."

BERNHARDI'S APOLOGIA.

[In the New York Press the author of Germany and the Next War has explained the purity of his own and his country's attitude; and has followed up this defence with a résumé of the War, completely favourable to Germany, and corresponding in scarcely a single detail with the facts.]

Their staff of life a broken reed

(No doubt a Teuton bluff designed

To make the hearts of neutrals bleed);

But you, Bernhardi, you at least

Need never know an aching hollow,

Who have, for your perpetual feast,

So many swelling words to swallow.

Such as Przemysl never faced,

And show at last, with hands in air,

A heavy bulge about the waist;

For, though the cud that you have chewed

Has cost a deal of masticating,

I think you never handled food

So rich, so meaty, so inflating.

You leave your rôle of warrior-seer,

To re-create the past instead

For long and innocent ears to hear;

And in your twopence-coloured tract―

Its Teuton touch so light and airy―

Dull History, disengaged from Fact,

Debouches on the bounds of Faerie.

Your effort in The New York Sun,

"What will the other liars say

When they perceive their gifts outdone;

When they suspect, what now I know

Who hitherto retained a bias

In favour of the Wolff Bureau―

That you're the leading Ananias?"

O.S.

UNWRITTEN LETTERS TO THE KAISER.

No. XVIII.

(A Fragment from G**rg* B*rn**d Sh*w.)

... but when I am asked to go a step farther I really must cry Halt. For the truth is that you yourself, with your awful nod and your glittering uniforms and your loud meaningless talking and your sham religion and your fondness for poor jokes, are merely one of the superfluous things of which the world is full. Nobody who knows me will suppose that, because I have chosen an inappropriate moment for showing up my fellow-countrymen, I am therefore likely to sing hosannas in your praise. What I see in you is, as I say, a superfluity. What you see in me Heaven knows, and I think I can guess. It is intellect, pure intellect, and in paying attention to what is represented to you as intellect you imagine you are acting up to the traditions of your family.

To be sure your predecessor didn't make much of his intimacy with Voltair. When all is taken into account the sneering ill-conditioned old writer has the best of the quarrel, though no doubt the King had his happy moments when he set the philosopher shrieking his woes all over Europe. No, I don't like the precedent. I cannot imagine myself at Potsdam any more than I can imagine you at a general meeting of the Fabian Society. By this I don't mean that there are no worse places than Potsdam, any more than I mean that there are no more delectable discussions than those of my beloved Fabians. All I mean is that you and I, both of us admirable men in our way, had better keep ourselves to our own pasture grounds and not try, as you are trying, to encroach upon those of our neighbours. What should I do at Potsdam? It is possible, perhaps, for a German to have esprit―to be light and witty in conversation, sympathetic in his intercourse with others, unpedantic and rational in his judgments; but if we may assume the existence of such a German we may at the same time be quite certain that we shan't find him in Potsdam or in any place that has the true Potsdam qualities, with its tame Professors, its stiff military heel-clickers, its intolerable heaviness in the intellectual atmosphere and its calm assumption, maddening to a mind like mine, that Germans are necessarily right because they are Germans. To be patronised by a Professor or a General, and above all to be patronised in the German language, would be death to me in something less than ten minutes. I don't want to die and I do want to go on writing prefaces to my plays, so to Potsdam, the Canossa of the spirit, I, at any rate, refuse to go.

May I remind you, by the way, that Frederick, your supreme model and Carlyle's favourite, was in some points but a poor German. Prussians he thought excellent as material for filling up casualty lists, but beyond that he doesn't seem to have cared to give them much power. As to the German language, he had the utmost contempt for it as a medium of intercourse between civilised human beings. Next to his ambition to win fame and rob Maria Theresa he had one ardent desire―to shine as a master of the French language. He deluged Voltaire with his efforts in French poetry. After he had defeated Soubise in the battle of Rossbach he sat down and composed a perfectly execrable copy of French verses, in which he held his enemy up to the derision of mankind in an abominable series of insults. The badness of the lines may perhaps be taken as a strong proof of his patriotism. Have you ever read them? And, if you have, what do you think of them?

You are certainly wrong when you declare that the German case in this War must commend itself by its not-to-be-broken strength to any candid mind. No mind could well be more candid than mine, and I can only say that, having read with great reluctance much that has been written on the subject by Germans, I have come to the conclusion that your German case is the worst of all those produced by the War. In comparison the case of England is crystal clear, and even the case of Austria takes on a certain amount of reasonableness. If you ask me why I don't say that in England, I reply that that is not my way. To pour cold water on the opinions of one's countrymen is the best plan for getting oneself talked about―better even than putting on a silver helmet and spouting Imperial rubbish before an Army Corps. And if one makes a howler about the history of the United States and the proprietorship of Alaska so much the better. It isn't everybody who can get himself corrected by a schoolboy.

Yours at a distance, G. B. S.

The Truce.

"Our readers are earnestly requested to support heAdvertisers in the paper."―The Common Cause.

Appearing in an organ of the feminists this shows a most forgiving spirit

"All Germany wanted from Russia was that she should not continue to be the hope of the Slaps."―Newcastle Evening Chronicle.

If Germany wanted to attract the Slaps to herself she has succeeded beyond her wildest hopes.

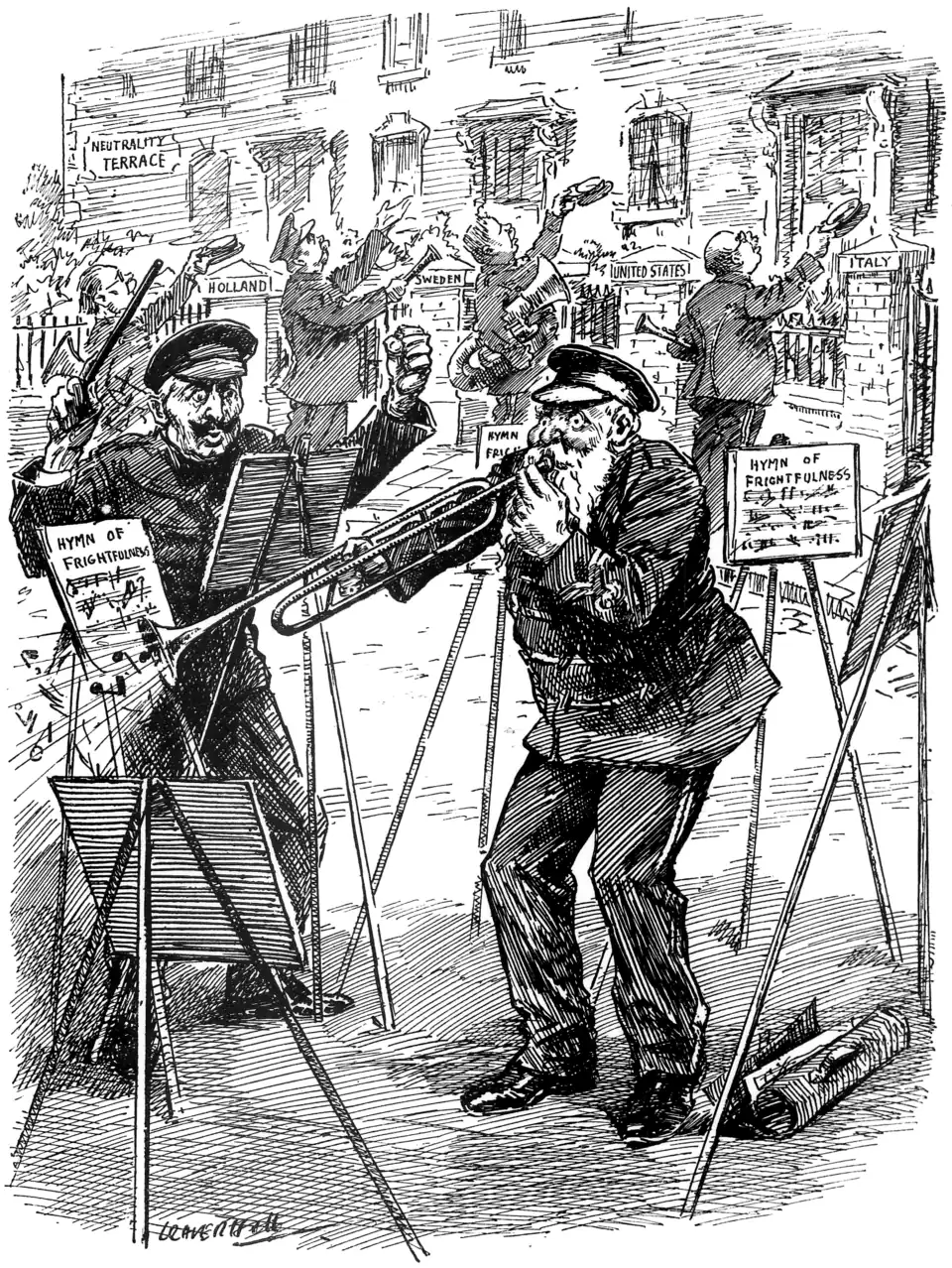

A BRAZEN BAND.

Imperial Conductor. "STICK TO IT, TIRPITZ. KEEP ON MELTING THEIR HEARTS!"

A TOO GREAT SACRIFICE.

Jones (after half-an-hour with the bugle band). "I must chuck this. After all—why ruin one's face?"

A WAY WE HAVE.

Pte. 111111 Wilks had had a bad night. The result was that he found himself a few days later charged with:

(1) When on guard being drunk at his post.

(2) Mistaking the C.O. for a rabbit and shooting him in the leg.

(3) Striking several of his superior officers.

(4) Laying-out the Quartermaster.

(5) Losing by neglect one sock value fourpence.

Second-Lieutenant Smithson found himself attending the court-martial "for instruction." He was duly instructed.

*****

The preliminary proceedings were lengthy, but with the help of Captain Hake's Manual of Military Law and Captain Halibut's King's Regulations and Manual of Map Reading the President got through them satisfactorily. After twenty minutes' hard writing he looked up at the junior officers under instruction, and, realizing that they were losing interest, gave them permission to think. Second-Lieutenant Smithson accordingly abandoned himself to thought . . .

The pisoner having been brought in, the Court was then sworn. The President swore Captains Hake and Halibut and Captain Hake swore the President. It was now Captain Halibut's turn, and he swore the junior officers. There were about fifteen of them, and he decided to swear them all together on the same book. In the mélée which ensued several thumbs were unplaced and most of the others were left unkissed.

The prisoner pleaded "Guilty" to the first four charges and "Not Guilty" to the fifth. The Court was completely upset by this, and Captain Hake had to lose himself in the 908 pages of Military Law for some hours before it regained its calm. The President then announced that he would take Charge 5 first. A very young subaltern, who was still suffering from the shock of having his thumb kissed simultaneously by two perfect strangers, dropped his sword with a clatter into the fender and spent the rest of the day trying to get it back into its scabbard. It seemed to have got bigger somehow. . .

The evidence was then read. It was to the effect that Company Quartermaster-Sergeant Sturgeon deposed that on-or-about-the-5th-ult.-he-had-served-out-one-pair-of-socks-value-eightpence to-the-accused-and-that-on-or-about-the-22nd-inst.-the-accused-was-found-in-possession-of-only-half-a-pair-of-socks-cross-examined-by-accused-did-I-only-have-half-a-pair-of-socks-Company-Quartermaster-Sergeant-you-did.

The Prosecutor rose. He said that the accused, on or about the something ult., had had one pair of socks served out to him, value eightpence, and that on or about a later date (inst.) he was only in possession of half-a-pair of socks. Consequently he was charged with losing by neglect one sock, value (approximately) fourpence.

Company Quartermaster-Sergeant Sturgeon was then called.

President. Now then, just tell us what happened.

C.-Q.-M.-S. Sturgeon.—Sir, on or about the fifth of February, nineteen hundred and fifteen, I served out to the accused, one pair of socks, value eightpence. On or about the twenty-second of March, nineteen hundred and fifteen

This was the third time Second-Lieutenant Smithson had had it in full, and he yawned slightly.

President. Yes. Now I must write that down. Begin again, and say it slowly.

C.-Q.-M.-S. Sturgeon.—Sir, on or about the fifth

President. On—or—about—the—

At this point the President's nib broke, and the youngest subaltern but one was sent out for a stronger one. He rose, put his cap on, walked to the door, turned round, saluted, went out, sent somebody for a nib, came in again, saluted, took his cap off and sat down. Second-Lieutenant Smithson sighed and envied him his busy morning.

President (finishing his writing). Yes. Now I'll just read that to you. "On or about the"

("That's the fifth time I've heard it," said Smithson to himself, "I hope it will be useful at the Front").

A junior officer, who had described himself as Prisoner's Counsel, but, on the emergence of Captain Hake from the middle of Military Law twenty minutes later, consented to answer to the name of Prisoner's Friend, rose to cross-examine.

Prisoner's Friend. What makes you think that

The Prosecutor jumped up and said that on page 79 it was distinctly laid down that the Prisoner's Friend was not allowed to cross-examine until after the verdict.

Captain Halibut (turning to page 79). There's nothing about it here.

The President pointed out to Captain Halibut that he was consulting the Manual of Map Reading. Captain Halibut apologised and suggested that a window should be opened.

A heated discussion followed. Prisoner's Friend said that he only wanted to ask the witness if he were quite certain. Witness said at once that he was. Prosecutor said that he wanted to say some time or other, and he didn't much mind when, that shooting your commanding officer in the leg was a very serious thing. President assured him that, as prisoner had already pleaded guilty to this, nothing more could be said on the subject. All Prosecutor could do was to point out the heinousness of losing half a pair of socks. Prosecutor promised to do this.

The day rolled on . . .

At about 3.30 P.M. the Court was cleared. The Prosecutor went out under protest.

"Guilty?" said the President to the two captains.

"Does it matter?" said Captain Halibut. "He's pleaded guilty to much worse things."

The President thought it didn't matter much, but Captain Hake pointed out severely that in that case the whole day of one major, two captains, an adjutant and fifteen subalterns had been wasted—an incredible thing to suggest. "Besides," he added, "it's a question who is going to pay for the new sock."

"True," said the President; "then let's give him the benefit and say, 'Not guilty.'"

Captain Hake fell into the Manual of Military Law and explained how this should he entered . . .

Second-Lieutenant Smithson woke up for the third time.

"And now," said the President at last, "the sentence. He turned to the youngest subaltern. What do you suggest?" he asked.

The youngest subaltern had just got his sword into its scabbard at last. He jumped up, said "Death" huskily, thought of the prisoner's mother and altered it to "Admonished," and sat down.

The President turned to the next subaltern.

"Reduced to Corporal," said the next one briskly.

"He's a private already," said the President, consulting his papers.

The subaltern lost his head. "Promoted to Corporal," he amended lustily, and hid himself behind his cap.

The President decided to consult the two Captains. . . .

And that, you think, is the end. How stupid of you. It turned out that Captain Hake's name was really Captain Hike, a fact which of course washed out the whole proceedings. So another court-martial was held, and Second-Lieutenant Smithson, again up for instruction, heard C.-Q.-M.-S. Sturgeon's evidence five more times. And even that didn't settle it; for at the end of the second court-martial the convening officer made another discovery. Second-Lieutenant Smithson fancies it was that Prisoner's Friend had paraded in court with the upper lip shaved contrary to the King's Regulations, Sect. XII., par. 1696; anyway there was a third court-martial, and for the fifteenth time Second-Lieutenant Smithson heard the words: "One pair of socks value eightpence." Ho knows them by heart now and is introducing them into a little handbook he is preparing. It is called Lightning Training in War Time.

A. A. M.

PERCY'S PROGRESS.

"Curious thing, Reggie—these chaps drillin' everywhere used to bore me awfully, once; but now I find I rather like watchin' 'em. Sprt of thing that seems to kind of grow on one."

The New Hellenism.

Touching the advance on Constantinople "A. G. G." in The Daily News wrote recently:—

"It is not unduly fanciful to see in it a modern counter-part of that legend of the Greek fleet that sailed up those same waters to Troy to rescue the ravished bride of Agamemnon."

Pardon us, but we think it is unduly fanciful. Agamemnon had enough marital troubles of his own to bear without being saddled with those of brother Menelaus.

Bane and Antidote.

"Wanted at once, chest of drawers and piano for learner."

Edinburgh Evening News.

"I wonder," writes the sender of the above, "what a learner can learn from a chest of drawers." We have found the answer. He can learn to shut up.

Woman's Weekly.

The arithmetic may seem peculiar, but something must be allowed for the labour, and besides, the ¾d. gives such a realistic touch.

Bus Driver (much annoyed at zigzag course of coal-cart). "Hi! Wot yer think you're doin'? Dodgin' a submarine?"

THE ROAD TO BERLIN.

I'm looking for the man who designed the "Silver Bullet" puzzle. I have something to say to him that won't keep.

What's so maddening is Peter's attitude towards the wretched thing. He comes in from school, sees it lying about, picks it up any old how, gives it a few really hard shakes, a pat here and a bang there, and the bullet is where good British bullets should be in Berlin.

He doesn't even give his mind to it while he's doing it, but goes on whistling the air which was in progress when he arrived home.

Peter is rising nine, and I'm a few inches over forty-seven, and a special constable with prospects of early promotion, but I haven't succeeded in mastering the puzzle yet.

Yesterday Peter went over the course a dozen times in as many minutes. "You have another try, Daddy," he said.

"Well, only one," I said.

I got as far as Magdeburg for the first time in my life, and determined to have one more. "Absolutely the last," I said.

It was then 8.10, and at 8.46 I think Peter was sorry he had tempted me.

"Look here," I said, "you may stay up till I've done it, for a treat. I shan't be long. I nearly did it that time. I got past Hanover."

"Thanks," said Peter, "but I have to go to school in the morning. As you're busy, I'm going to bed now."

I was busy. I'd reached Hamburg three times, and the lust of conquest was heavy on me. It was at 11.15 that the flower-vase went. Dresden was responsible for that. There is a horrible swan-neck curve as you approach the town from Leipzig, and I tried one of Peter's sideway jerks. Still, if I hadn't been leaning over the table to get the full benefit of the electric light which hangs over it, Alison's favourite bit of glass might have gone on a little longer.

Towards midnight Alison called to know if I was aware of the time.

"Hush!" I said; "I'm just outside Berlin. The Germans might hear you. I've got to Potsdam."

I shouted the last syllable because at that moment the bullet slipped down the hole. By 12.30 I had reached Potsdam four times, and four times the accursed Bosches had mined the road and swallowed the advancing foe.

It was not till 1.17 that by an unparalleled feat of dexterity I got the bullet past Potsdam, and Berlin fell.

Unfortunately the rest of the apparatus fell with it, and the glass broke.

That was the price I had to pay for Peace, but it was worth it.

At G. H. Q.

"My interview took place in large and well-lighted room, the sole furniture of which was a huge table spread with maps and some armchairs."—Daily Telegraph.

It must have been "some" table, too.

In the North Sea Squadron they refer to the Kiel Canal as Fleet Street.

"Those who may wish to supplement Loss of Capital sustained by depreciation in the value of investments which hitherto have been regarded as contributing the main provision for their families should write for particulars of a special scheme for this purpose."Advt. in "Irish Times."

With "racing as usual" a special scheme seems superfluous.

WAR NEWS FROM ITALY.

Rome, March 26th, 1915.

I think it may interest you to know what the Press here is saying about the War. In Italy we do not have "Stop Press News" or "Latest News from the Front." We browse instead on "Ultimate Notices" and "Recentissimies" (an Ultimate Notice bearing about the same relationship to a Recentissimy as a London "egg" to a London "new-laid egg"). The language also possesses the advantage of enabling one to make short work of places like Lwew (Leopoli is both elegant and practicable), though towns consisting purely of consonants remain the same Shibboleths here as elsewhere. We have apparently several sources of information, and from a general sifting of telegrams I have come to the conclusion that those headed G.E. are trustworthy, while those preceded by E.V. are not. Caterina, who makes periodical sorties from the kitchen to proffer pantomimic assistance when I am in difficulties, suggests that they all emanate from the Devil; but then she is a Sicilian.

"(G.E.) One announces from Londra, and The Daily Mews annexes grand importance to this telegram," etc., is read with interest and only slight mental reservation. "(E.V.) From Berlino by radiotelegrafy" (we read on for fun) "one is informed that ten English ships of war became sunk in the sea of the North after a sconflict with our torpedoes"; or telegrams headed, "The War reflected from Berlino," are frankly dismissed with a smile of superior wisdom or an impatient shrug.

You must not suppose that because Italy is neutral she is sparing of headlines and large type; on the contrary, we indulge in these in a most liberal manner. Then, too, regarding our official news, we are not to be put off with such dry stuff as the consolidation of positions round Perthes or slight progress near to Berry-au-Bac. We have instead strictly neutral guesses of an agreeably titillating nature:―

"The Russians respinted from Polonia?" "The defunct general Haddanuffsky shall have been resurrected?" "80,000 prisoners and four mitragliatrices impadronited by the Austrians?"

Unfortunately other sentences apparently guileless are not all that they seem, and Caterina's gestabulary is not always equal to coping with them. On the other hand, "The German State Major has prepared since a long time a vast and complex piano," etc., is obviously sheer rubbish.

Some gems I secrete from Caterina, and hug them in all their fascinating obscurantism to my British bosom. For example―"Scontri fra pattuglie di cavalleria nelle trincee nel pomeriggio del 24." I often brood over this. Scounters between pattugles of cavalry" opens well enough; but the rest seems to be a conundrum.

The Italian language is nothing if not courteous. Note how amiably it refers to its but lately bitterest enemies: "Discomfiture of two Turkish divisions." On another page of the same issue popular satisfaction would appear to have outrun editorial courtesy: "Turks slogged from Tschoroch. Ottoman defeat complete." Caterina was too mild over "sloggiati," inferring a pushing movement; perhaps, however, the Italians, being a Southern race, slog more gently than the Russians.

We do not feed solely on Allied and German telegrams. We have independeut comments of our own on the War in general. We examine the conditions on the two fronts dispassionately, and though one writer in The Courier of the Evening is inclined to believe that it will take the Allies thirteen years to reach Cologne, on the other hand a more hopeful gentleman entertains the opinion that the new English armies will upset the squilibrio (apple-cart?).

Caterina and I discourse non-committally on the chances of the "War of Dirigibles and Submergibles," Caterina on the whole favouring the Zipiloins. Colourless anecdotes and recently-fulfilled prophecies round up our daily mental fare. Sometimes by way of a bonne bouche we have a horoscope of the Kaiser (Guglielmo). And so from the huge Recentissimies of the War we descend to the small beer or "Little Chronicles":―"The Parisian Pythoness;" "Grave suicide of promised spouses; identification of these." Finally we peruse with languor the advertisements or "Little Publicities," for after all the journalistic emotion we have been through we feel as though we had actually been struggling with the Germans in Sciampagna and Fiandra, and were really taking our share in the great cataclismo (world-sconflict).

"18,000 words often mispronounced, W. H. P. Phpfe."

Advt. in Hong Kong Daily Press."

If Mr. Phpfe can pronounce his own name correctly, there can scarcely be 18,000 words that present difficulties to him.

"The Railway Department announces that arrangements have been made for a reduced train service, whereby a million males per year will be 'saved.'"―Sydney Daily Telegraph.

Saved for the line, we hope. With this splendid Australian example before them our own railways can surely spare a few more men for the colours.

OUR SKI SECTION.

On the whole ours is a good corps. We have bits of most things, but for a long time lacked a ski section. I mentioned the matter to our Commandant, not in the spirit of reproach but of suggestion. After considerable hesitation he gave me permission to raise one. He is rather old-fashioned in his ideas and seemed to doubt the practical utility of the section. He even talked about the approach of Summer. He has spent the last few years in India and forgotten the rigours of an English May. I pointed out to him that France might well reproach us with not taking the War seriously when we were not even training skiers to meet Anton Lang on equal terms should he land on the East Coast from Oberammergau.

I was lucky in getting a nucleus, consisting of two men who had skied before, three who had seen skis, and four who had heard of them. We bought up a derelict stock laid in before the War in anticipation of Winter sports.

As the snow harvest in this country is somewhat uncertain, I decided to start drilling without waiting for a fall. I had some difficulty in getting the squad to form fours neatly. I had to reprimand Bailey several times for treading on the skis of his rear-rank man. Bailey didn't properly understand the things and would insist that they had sent him an odd pair.

Our most effective turn was marking time. I am told that we could be heard two miles off, and that a number of people mistook us for a pom-pom in action.

I have had several offers of Music Hall engagements if I can get my men a little more effective.

The section had standing orders to mobilize at the top of Ludgate Hill at the first sign of snow. I thought that this would be a nice easy slope for them to start practising on. Our first mobilisation was rather a fiasco owing to the unsatisfactory nature of the snow. Several flakes looked like setting, but were run over by motor-buses in their early infancy.

On the second occasion our manœuvres were spoilt by the obstinacy of the Commissioner of Police and the Corporation. The former refused to stop the traffic, whilst the employés of the latter made spasmodic efforts to steal our snow. This led to confusion, the permanent loss of one man to our corps and the ruin of three pair of skis. It was unfortunate that the motor-bus and our casualty both skidded at the same time and in one another's direction. I think that the motor-bus was to blame, because the skier started his skid first. Bailey carelessly did the "splits" in front of a taxi and got his skis run over. I have launched an action against the motorist who got my right ski mixed up with the spokes of his off back wheel. He oughtn't to have come so close just as I was getting up from a lying-down position.

Before we were really used to the business the Corporation men got away with the best part of the snow and we had to adjourn to Hampstead Heath.

We lost three more men on the Heath, as the snow wouldn't lie evenly on the slopy bits. I hadn't much sympathy for one man who would go down the hills backwards. I told him that he was sure to bump the back of his face.

Those of us who took train to Derbyshire found some good snow and got some useful experience. We mightn't have had so many serious accidents if I had kept them to extended order drill. They confused battalion drill with company drill. When I ordered them to "form section" they usually "formed mass," and the subsequent sorting wasted a lot of time. Our professor of mathematics confused the order up with conic sections and spent his time describing parabolas. Higgs went back at the end of the first day in anger because we refused to waste the whole afternoon looking for half-a-sovereign which he said he had lost in the snow.

We found our rifles a nuisance, and Bailey and Holroyd nearly came to blows. Holroyd declared that Bailey had wantonly tried to bite off the foresight of his rifle so as to prevent his winning the shooting trophy. Bailey was most unfortunate. He seemed to go out of his way to get hurt. It's quite an acrobatic feat to get the point of one's ski in one's own eye, but Bailey managed it. I never could get the section to lie down simultaneously; nor could we find any satisfactory method of keeping in touch with our rifles or concealing our legs and skis from the enemy.

As soon as I found out how rusty other men's rifles got I wasn't so upset at having overlooked mine in the snow.

When the thaw set in the four of us who were still out of hospital decided not to volunteer for service with the Alpine Chasseurs but to stick to Home Defence. We have arranged to suspend operations until we get some recruits to fill up the vacancies. Ski-ing isn't as simple as it looks in the pictures; there's always the chance that a damp cartridge won't go off.

I may have more to say on the subject when we begin manoeuvring with fixed bayonets.

THE REFINING INFLUENCE OF WAR.

The Victor. "Now, I s'pose I got to give you first aid."

Another Dog of War.

"With her wounded bull hound in collision mats... she remained afloat and was safely guided into drydock."

Montreal Daily Star.

This hitherto unrecorded casualty will be read with sympathy by his brethren of "the bull-dog breed."

A Generous Administration.

"PERTH, Sunday

Some time ago members of the Scaddan Ministry mutually agreed among themselves to give at least 0 per cent. of their salaries to the War Distress Fund.

Payments of the kind were kept up for some time, but lately they have ceased. The matter is now the theme of general comment."

Sydney Morning Herald.

If this statement is accurate―which we take leave to doubt―the West Australian Ministers would appear to have acted upon the time-honoured principle―"What I gives is nothing to nobody."

Our Veterans.

"St. James's Palace, where Lord Kitchener is now settled, has not been used as his Royal residence since the time of George IV....

Vice-Admiral Carden, who is in command of the fleet at the Dardanelles, has been in the navy since 1807!"―Lurgan Mail.

Lord Kitchener seems to have the advantage in rank (being apparently of Royal blood), but Admiral Carden beats him by several years in seniority.

"Let nobody say to himself, 'Among the untold millions of money our Anna's 100 marks do not count.' Rather let everybody consider how many Annas there are in the German Empire with a hundred or several hundred marks. All these hundred marks together make several millions. If every Hausfrau were to think 'Our Anna's 100 marks do not matter,' all these millions would lie unused."

North German Gazette.

We understand that in India 16 Annas go to a Rupee. How many will Germany require to cover the War Loan?

Old Lady (to nephew on leave from the Front). "Good-bye, my dear boy, and try to and find time to send a postcard to let me know you are safely back in the trenches."

THE BIRDS OF ST. JAMES'S.

(A pleasant after-luncheon jaunt)

To woo digestion and to mark

The varied waterfowl that haunt

St. James's lake; the scene was drear,

For men have drained the local mere.

Lies arid concrete, chill and bare,

But just beside the Whitehall gate

One sorry pool remains, and there

Such homeless birds as love the damp

Have formed a concentration camp.

The pelicans' exclusive club

Contrived to win from passers-by

Most of the notice (and the grub),

Coarse rowdy riff-raft throng the plat,

A vulgar proletariat.

To race with widgeon, coot or teal,

Nine times in ten get badly pipped

When sprinting for the casual meal;

From their demeanour I inferred

That this is apt to sour a bird.

Observing an unwelcome fast,

Each mourning in his secret heart

The dear undemocratic past,

Before the bbing of the flood

Had set aside the claims of blood.

AN EASTER CALL FOR SACRIFICE.

Londell's rooms are two―one to sleep in, and the other to bolt toast in. I found him in the breakfasting chamber. On the table was a basin of hot water; Londell, with a small sponge in his hand, was gazing sadly at a Gladstone bag.

"Forgive me for intruding on this busy bath night," I said. "I have looked in to remind you of our Easter engagement. This time, try to avoid packing odd boots for your spare pair."

"I don't think I can come away for Easter," he said gloomily; and he fingered the sponge as one in a dream.

Something had depressed Londell; he wanted rousing. I went and helped myself to one of his three remaining cigars, but it had no effect.

"If I had another bag," he went on, "it might be different; but this is the only one I have."

"What's the matter with it? Quite a good bag, it seems to me."

Londell pointed to it in a way that made me think I had never before seen him so like the late Sir Henry Irving. "There," he said, "is the work of half a lifetime. That collection is among the best in the Temple. I have lavished time and thought, ay, and money upon it. It has cost me two hundred pounds if it has cost me a penny. Am I to sacrifice all for the sake of a paltry four or five days at the sea?"

"I don't know what you're talking about, but I feel sure you're wrong."

"I don't mind the Chamonix one, or that little chap under the buckle there―the one from the Canaries. But how could I face Bournemouth with all those German and Austrian hotel labels on my bag?"

The Trojan Horse Outdone.

"PARIS, Tuesday.―After the Frenchmen's fruitless efforts to capture the strongly-held position at the Great Dune, twenty-four Algerians, concealed in the bellies of horses, appeared in the German trenches at nightfall. When the Germans were about to capture the horses, the response was a sharp cry, and the Algerians galloped back to the French lines, whereupon twenty-four grey forms rose from the ground, and threw themselves into the trenches."

Sydney Daily Telegraph.

The Arab horse's powers of initiative have evidently been under-estimated.

A remarkable instance of putting the car before the horse. "The Kaiser, on a white horse caparisoned in purple, angrily stepped into a motor-car and went to Lille."―Waikato Times, N.Z.

THE HAUNTED SHIP.

Ghost of the Old Pilot. "I WONDER IF HE WOULD DROP ME NOW!"

[April 1st is the hundredth anniversary of Bismarck's birth.]

A NORTH-COUNTRY IDEAL.

The Belgian army stood on the top of a mound brandishing its trusty pinewood blade. The rabble of Germans, recovered from one rebuff, was gathering forces for another charge. The Belgian army changed its sword from the right to the left hand, drew out an imaginary watch, and consulted it severely.

Its defiant voice rang out through the sharp air. "I'll give you," it cried―"I'll give you ten minutes to clear out of Belgium."

The dramatic hush after this ultimatum was broken by the hurried clamour of the school bell. Allies and enemy alike showed a jumble of red knees and flying heels as they rushed schoolwards across the field.

The Mistress paused on the way to her desk.

"Take your slates," said she, "and with very good writing and very good spelling tell me what you are going to be when you grow up. Even betting on Frenches and Jellicoes," she murmured as she sat down.

A busy silence fell on the schoolroom. The open fire crackled cheerily and warmed away the circles of frosty air each little combatant had carried in with him. Pencils scraped, or were sucked audibly as a help to intellectual wrestling. Bobby―the army of the Belgians―had rubbed out his beginning three times with a wet and grubby forefinger, and was squeaking along the dark wake in a fourth attempt. Spelling was no trouble to him. A difficulty is not a difficulty if you sternly refuse to recognise it as such; but he had worries not unconnected with the shape of the more knobbly letters.

The voice of the Mistress broke the silence. "Boys, stop writing; stand and turn your slates."

The little line of boys stood, slates held firmly forward to be read. The Mistress went slowly along. Outwardly she marked with thin chalk and talked of spelling and capitals and suchlike mysteries. Inwardly, she kept count. One small finger of the left hand was tightly folded in for each Admiral, while the Generals, Lance-Corporals and Field-Marshals were counted with the right. At the end of the line five fingers of each hand were firmly doubled in and it was difficult to hold the chalk.

"All square," said the Mistress softly, "and one to go. Bobby for the casting vote."

Bobby's slate was still turned towards him. With infinite pains and much puffing he was putting the final touches to his treatise.

"Come, Bobby," said the Mistress, with interest, "are you a brave defender too?"

"Yes,m," said Bobby.

"What is it with you? Land or sea? A soldier?"

"Yes'm," said Bobby, beaming.

The chalk, held in her right hand, snapped.

"Well, she said, "is it a Captain? or a General? or"―with awe, as the vision of a burly three-striper, much adored by the boys, crossed her mind―"can it be a Sergeant, Bobby?"

For rank Bobby cared nothing. A soldier, to him, was a man who stood against fearful odds, Uhlans and things, and beat back the rascally foe. One word, heard often of late, had come in his mind to stand for this. He had IT in his essay.

"Come, let me see," said the Mistress.

Proudly he turned the slate. Bobby's essay ran clear through the smudges of much strife―

"Im goin to be a Beljum."

Sandy (member of a martial family, returning from tea with some friends of a like age). "I'm glad I took my gun, Mother. Jack and Mollie haven't a single weapon in the place. Why, you wouldn't know there was a war on!"

An Oxford correspondent kindly sends us the following extract from the catalogue of Sir Arthur Evans' Cretan Monographs:―

We are sorry that Sir Arthur thought it necessary to part with "skytotes"; it is just the short word we have been wanted for aeroplanes. "Erratum.―Page 17, note 1: for 'sky-totes' read 'rhytons.'"

JIMMY.

I don't know if you are having the measles at your house. We are. They're on me. They are not half bad, really. You have to sicken for them first and then you get them. The doctor came to see me have them. He gave me a cynical thermometer to suck. He tied a piece of string to it first because he said that it was a one-minute one. I don't like the taste of thermometers. I bit one once and the end came off and disagreed with me. Jimmy says when they put the thermometer in your mouth you have to see how far you can make the mercury move up the tube. Jimmy can make it move up to the top every time. He says you have to hold your breath and then blow. The thermometer wouldn't boil, so the doctor told me to put out my tongue at him. The last time I put out my tongue at someone I had to have it impressed on my mind not to; it was over a chair.

So I asked the doctor if it wouldn't do if I made a face at him instead. I am not so very good at making faces. Not as good as old Jimmy. He can move his ears. And his scalp. Jimmy says very few people can move their ears really well. He can do it one at a time, but he won't do it now unless you give him two pen-nibs. He is collecting pen-nibs. He says if you collect a thousand pen-nibs you get a bed in a hospital.

They made me put out my tongue at the doctor. When it was all out the doctor said it was a very nice one. Then he took hold of my wrist and looked at his watch. I asked Jimmy what the doctor looked at his watch for. He told me that measles made the watch go slower, and if it stopped you were dead. Jimmy said that his wrist always made the doctor's watch stop. I asked him why he wasn't dead then, and he told me it was because he could move his ears. Jimmy says he always kept moving his ears while the doctor was busy with him.

I had the measles all right. I had only a few at first, five, I think, and the doctor said I ought to keep them tucked up or else I should catch the complications. I asked Jimmy what the complications were. He had come quietly up our backstairs to see me and the measles. I told him he would catch them too. But he said he wouldn't if he kept moving his ears. Jimmy said he knew all about the complications. He said he had done them in arithmetic; they came next to decimals and were things where the numerator was bigger than the thermometer.

When the doctor saw me next day he said the rash was well out. I know that, because I had given up counting them. The doctor said I should have to have the quarantine next.

1 asked Jimmy if he had ever had the quarantine. He said it was stuff you put on your hair to make it shine.

Jimmy brought me a caterpillar and two thrush's eggs in a matchbox. I asked him why the rash came out all over me. He said it was the measles and that they had to come up to the surface to breathe. He said if I would let him vaccinate me with his pen-knife they would all go away. Jimmy is going to be a doctor―when he grows up. He said it wouldn't hurt me if I held my breath. But I wouldn't let him. I said he might taste some of my medicine though, and he said he knew what it was made of. He said he could make me up some much better medicine than that. It was medicine that the Indians always used. They made it out of the bark of trees, and it would cure warts as well as measles. He said there was a certain way of making it that wasn't found in books, because it was only when an Indian was going to die that he told anyone how to make it. Jimmy said it was splendid stuff, and that, besides curing warts and measles, it would make boots waterproof. Only the cleverest doctors know about it, Jimmy said, and they daren't tell anyone lest the Indians should get to know, and kill them.

The doctor said I might get up and have the quarantine downstairs. He said I wasn't to go near anyone or they would catch it. He said I looked very happy. I was. You see the doctor had sat down on the chair on which I had placed the thrush's eggs. Jimmy says it is unlucky to sit on thrush's eggs, but that you can make it all right again by counting ten backwards. That was what the Indians did, he said.

I didn't mind the quarantine a bit, though it made me feel weak in my legs at first. Jimmy said that the best thing for weak legs was to walk barefoot through nettles. He said that the Indians made their children do that, and that was why they could run so well. Jimmy made me some medicine out of a rare kind of root he had found by accident. It smelt like cabbage. He said it would make me feel very hungry and that he always took some at Christmas time. A gipsy had told him the secret in confidence in exchange for a pair of his father's boots which he thought his father had done with.

When I was nearly well from the quarantine Jimmy and I arranged to go fishing. He said he had some stuff which attracted all the fish if you poured some in the river. He said that a poacher told him how to make it.

Jimmy says next to being a doctor he would like to be a poacher. He told me how to catch pheasants. All you had to do was to put some stuff out of a bottle on the ground, near where the pheasants roosted at night, and it would stupefy them. Then, he said, they fell out of the trees and you put them in a bag. He said the stuff was made out of herbs which came from Australia. It was very strong stuff, he said. Two drops placed on the tongue of a dog would kill the strongest elephant, Jimmy said.

We didn't go fishing after all. I waited for Jimmy for over an hour, but he didn't turn up. So I went to his mother's house. Jiminy lives with his mother. Jimmy's mother said that he was in bed very busy with the measles and that he wanted to be left alone.

PROOF POSITIVE.

Village Haberdasher. "Yew take it from me, Sir, folk in our village be very spiteful agin the Germans. Why, Oi reckon Oi've sold fifty 'anker-chers wi' Kitchener's face on 'em!"

A CHIMNEY-SWEEP FOR ENGLAND.

God bless 'ein, in the khaki line,

And I'd be in the thick of it,

With ten years off this back o' mine.

What's little cash and plenty black,

And kept me there, but still she's paid

Summat I'd die to give her back.

To let me fool I didn't shirk―

Some job as younger men could spare

For my two hands to grip and work.

Of luck at last. I've cleaned to-day

The chimneys at a house where folk

From Belgium's being asked to stay.

A lady got up off her knees―

She'd been a scrubbing―wants to know

How much I'm charging for it, please.

I'm charging nothing, Ma'am," says I;

"My hands was plaguing me afore

To let 'em work or tell 'em why.

Don't you forget as I'm the man

As wants a chance that lets him keep

On doing summat as he can."

A lady, her, and no mistake―

But smiled and held her hand and then,

Sooty or not, I had to shake.

Was all she said. I stepped out where

The kids was playing, sky was blue―

And me no cheat to see 'em tbere.

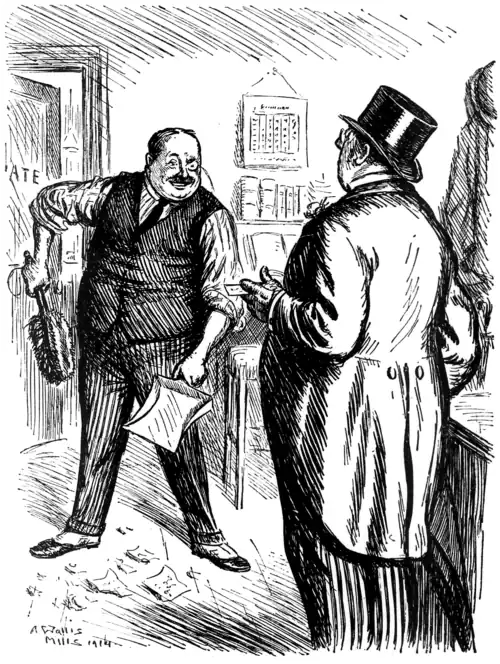

Head of Firm. "Come in, Sir. All my staff's enlisted. I'm office boy for the moment. If you'll tell me your bisuness I'll communicate with myself and let you know immediately whether I'm free to see you."

P———.

Among the advantages which we expected to result from the capture of a certain fortress in Galicia was a change of its name to something more easily pronounceable by British lips. Our hopes were a little dashed when we read in The Star:―

"The correspondent of The Daily News in Petrograd makes the interesting announcement that in future Przemysl will be known by its old Russian name of Przemysl."

On turning to The Daily News itself we were comforted by reading that the fortress "now resumes its old Russian name of Permysl," but were against thrown into some perplexity by learning on the same authority that the Archduke Friedrich had sent "greetings and thanks to the unconquered heroes of Permsyl." The spelling, however, is a comparatively trifling matter. The really crucial question is the pronunciation. The Daily News says, Prushemizel―the first syllable is very short"; but The Daily Express, in ppp tones, remarks, "Please pronounce it as Pschemeezel." From the newspaper authorities we then turned to the experts. Mr. Sydney Whitman boldly writes in The Evening News:―

"The true Slavonic pronunciation of Przemysl is 'Priz-ee-missile,' pronouncing these syllables in the way we pronounce 'quiz,' 'ea' and a 'missile'―a cannon-ball."

This seemed almost too simple to be true; so, seeing that Mr. Hilaire Belloc had been lecturing in Glasgow, we eagerly perused the report in The Glasgow Evening Times, hoping to come upon a really authorative utterance. Alas! for once Mr. Belloc failed to have the courage of his opinions, for this is what we read:―

"Mr. Belloc... pronounced it emisil,' though he cautiously gave no guarantee of correctness."

The great oracle having failed to give a certain sound, we were almost in despair. But rescue came from an unexpected quarter. "Our milkman," writes a correspondent in North London, "told us yesterday of the great Russian victory of Prymrosill." Light at last! A star has fallen from the Milky Way.

"While the capture of Memel, with its shipbuilding yards, manufactories of cement, fortifications, garrison and buns is regarded as unimportant from the strategic standpoint, it is recognised that it will have a great moral effect upon German opinion."―Star.

We understand now why the Germans were no determined to recapture it.

THE WATCH DOGS.

XIV.

Dear Charles,―A perfect spring morning; a clean, but rather idle street leading to an even cleaner and more idle railway station. Facing the station, half right, a café, and also facing the station, half right, myself and my brother officers full of good will towards humanity in general in spite of the execrable coffee and bacon we have just eaten. We sit on chairs on the pavè, and far above us in the blue sky flutters gracefully an aeroplane. It is an exceedingly pretty sight; it becomes even prettier when little white clouds suddenly appear round it from nowhere. If one happened to be looking when the little white cloud arrives, one sees a flash, but whether it is an English aeroplane being shelled by a German gun, or the other way on, no one seems to know, except perhaps the gentleman who is being shot at. From this picture you are requested not to recognise the nameless spot to which our thoroughly Unsentimental Journey through France has brought us.

The peace of the day was rudely disturbed at noon by the arrival of a more personal shell in the very midst of our billets. I am told that this was probably our own faults for being much too interested in that aeroplane. Apparently it was hostile after all, and experience goes to show that if people look up at these intruders their faces become apparent to the observer, and the notice taken of him encourages the enemy to do worse. The proper attitude is one of complete indifference. You should look the other way and then the enemy sulks and does nothing more. The arrival of this shell produced a most dreadful effect; it killed no one, but it caused every single soldier in the battalion to sit down at once and write to everybody he could think of, simply in order that he might mention, by the way, the bursting of a shell in his midst. This meant that every platoon-commander had to read and censor fifty letters before he could sit down and write his own casual references to bursting shells. This censoring of letters is altogether an inhuman and cruel affair; the lovesick private pours out his soul to his lady, concludes with all the intimate messages and signs known amongst lovers, and seals the note with the most personal of nicknames. What the lady must feel who reads the missive and finds at the end of it my own prosaic signature, I dare not think.

Since I last wrote we have stepped very many miles over the cobbles and have laid ourselves down to sleep in some very odd places. It is surprising how rapidly one can settle down to anything, and it is even more surprising how the men acquire the trick of getting what they want without learning a word of the language. They do it by a nice mixture of kindness and persistence; they go on naming the article in their own dialect until the peasant is fascinated or hypnotized into producing it. The most conspicuous success up to date is the case of our peculiarly insular sergeant-major, who, taking up a firm position before a simple maid-servant, continued tapping his forehead and smiling fatuously until the woman eventually led him up the street and pointed out to him the nearest way to the lunatic asylum. This was exactly what he wanted to know. When the Adjutant attempted to obtain the same information by mere conversation, he could get nothing better than a bucket out of the obsequious concierge.

Our entrance into the danger zone was very striking. We had been wandering about behind the lines, just within earshot of the guns, and looking for trouble, when the luminous idea occurred to some red-hat that, since we were dressed and looked like soldiers, we might as well fight. So we were sent for. A note came from someone, saying that they were giving a little party up-country, and they would be very pleased to see us there next day; would we mind walking, if it wasn't too much trouble? and also it would save the horses if we would carry all our luggage ourselves. Thus, armed with 120 rounds of ball, a tin of corned beef and an air of sinister importance, we tramped off in the direction of the noise.

Had Mr. Arthur Collins staged our night arrival on the battle-field in absolute accordance with the reality, the stalls would have said to each other, as they supped afterwards at the Savoy, "Very impressive, and essentially dramatic; but too theatrical to be real." It was exactly as in the picture: the long column advancing spasmodically along the straight road, bounded by rigid trees at regular intervals, and on the horizon the constant flashes of battle―the gun, the star-shell and the search-light. For myself I felt certain that it was all a show, and to encourage me in this opinion there were periods of inactivity followed by bursts of excessive energy, for all the world as if the electrician was sleepy and not attending to his business. War is, in fact, a disappointing imitation of The Lane, without the Savoy supper to follow. I should add that things went so well in our part of the line that we in reserve were not called upon: our baptism of fire was postponed; it is, in fact, taking place now, half the battalion being in the trenches as I write, and the other half (including myself) being for it to-morrow. I'll tell you all about it in due course.

As I write I can see out of my window all over the town (the owner of the house, by the way, lives in the cellar); my impression is of a vast area of urban and rural land, entirely at peace with itself and all the world; but there is a corner of it, about 200 yards from my window, which has a quarrel on with another corner about a mile away. These two little districts are making a terrible noise and even throwing things at each other. Sometimes they get very violent about it, sometimes they almost let the matter drop. It is like two large dogs barking at each other on Sunday, to the great annoyance of the rest of a respectable neighbourhood. And when the big dogs keep on doing it, the little dogs in the middle wake up and start snapping at each other, and particularly that quarrelsome breed, the Maxim. The main thing, however, is always the air of peacefulness, almost exaggerated peacefulness.

Yours ever, Henry.

BOAT-RACE DAY, 1915.

This morning brings upon the slip;

To-day no anxious cox exhorts

Care for that frail and shining ship;

The grey stream runs; the March winds blow;

These things were long and long ago.

All that is theirs is Hers to take:

Unfaltering service―heart and hand

Wont to give all for honour's sake;

They builded better than they knew

Who "kept it long" and "pulled it through."

No mounting cheer toward Mortlake roars;

Lulled to full tide the river lies

Unfretted by the fighting oars;

The long high toil of strenuous play

Serves England elsewhere well to-day.

A Triumph of Breeding.

"Mr. William Wallet disposed of about 150 head of Ayrshire and cross-bred calving queys and cows at Castle-Douglas yesterday. There was a large attendance of buyers in quest of the best class of Ayrshire queys, which, however, were scarce. Anything showing tea and milking properties realised the highest prices."

Scotsman.

THE WAR SPIRIT AT THE BRITISH MUSEUM.

Ardent Egyptologist (who has lately joined the Civic Guard). "No, I seem to have lost my enthusiasm for this group since I noticed that Bes-Hathor-Horus was out of step with the other two."

THE COLD CURE.

After a long period of immunity I have had a cold. To be precise, I still have it as I write, although it has once been cured.

The miscreant who cured it was a chemist in a West-end thoroughfare to whom I was so misguided as to confide my trouble. He had all the appearance of a man and a brother―in fact he looked benigner than most―and I trusted him. He listened with the utmost sympathy, his expression indicated grief and concern, and his voice took on a tenderness beyond that of a mother.

"I can set you right very quickly," were his brave words. "I have here a cold-cure that has never been known to fail. You take one of these little tabloids every three hours, and to-morrow morning you will wake up well. Be sure not to take more than six in the day," he added.

He held up the little bottle as though it were a jewel.

"And how much?" I asked, feeling that for such a boon no money was adequate.

"Two shillings," he replied; "and you might perhaps like to take one now."

I agreed, and with infinite solicitude he prepared a small glass of aqua pura and smiled at me like a bearded Madonna.

I went away feeling that complete recovery was merely a matter of hours, and for the rest of the day I was punctual with the tabloids. By night I had taken four.

I awoke the next morning not only full of cold, as usual, but with a splitting headache. When it was time to get up the room began to rush round me. Returning to bed, I fainted.

With great difficulty I dragged myself up, but all day my head swam and throbbed, and periodically I found it impossible to focus my sight on anything near by. Meanwhile I sneezed and coughed with more than accustomed vigour.

An instinct warned me not to go on with the cold-cure, and a medical friend corroborated my good sense by explaining later that it evidently contained some very powerful drugs, of which quinine was the chief, and I was suffering from them.

The next day my cold was worse but my head slightly better.

To-day my head is normal but my cold is terrific.

And now I want to know where I should be, in English law, if I were to stand outside that chemist's shop, as I long to do, preventing people from buying his cold-cure. What should I get, beyond Mr. Justice Darling's quips, if the chemist ran me in? Is it worth trying?

Missing.

"THE BUKOWINA.

AUSTRIANS REPORTED TO HAVE LEFT TRUTH HERE."

Liverpool Echo.

Recent "official" telegrams from Vienna tend to confirm the report.

AT THE PLAY.

"Rosy Rapture"; "The New Word."

Nobody would think of looking for intelligible motives or sequence of design in an ordinary Revue. Bu when Sir James Barrie writes one it's a different thing. He may deviate into fantastic episodes, but we suspect an ordered meaning in his main design and if we fail to find it we feel that the fault must lie with ourselves.

This was our trouble from the very start of Rosy Rapture. There was, in the first scene, a wardrobe, obviously full of portent, whose secretive purpose gave to the play a note of obscurity from which I never wholly recovered. Though this was not a bedroom scene, the wardrobe was hung with female garments, and, from it emerged, now and again, a husband in lieu of the regulation lover. After suffering a good deal of mental strain I reached the rather intelligent conclusion that we were supposed to be ridiculing the tendency of the modern stage to substitute the drama of clothes for that of intrigue. I recalled that in Kings and Queens, which was then still running at the St. James's, much stress was laid upon the young wife's passion for Parisian gowns, while the interest she took in her lover was merely casual and abortive.

It is not for me to question the cleverness of this solution, but it was wrong. I have since been credibly informed that the author was harking back allusively to certain plays of the past, not of great importance and long forgotten, in which a wardrobe was a prominent feature. But not even his ingenuous explanations offered at the close of the first scene lifted for us the veil of mystery that shrouded the motive of this piece of furniture. Nor was this obscurity relieved by the lighting of the auditorium, which was kept in darkness without intermission during the entire performance. In a mood of devotion I can persuade myself to support this arrangement when I assist at a Wagner rite; but the atmosphere of a Revue is seldom really religious.

It would have been more satisfactory if the author, in what was partly a burlesque of the legitimate stage, and partly a sort of Revue of Revues, had simply given us a succession of inconsequent scenes, and not attempted to weave his detached episodes into a connected scheme. Perhaps the best of them was a scene between a Flemish peasant girl (I call her Flemish by way of compromise, for she spoke French and looked Dutch) and a Tommy (American in the humorous person of Mr. Norworth), who had rescued her from the violent attentions of a Bosch. Excellent fun was made of their limited means of communication; but the chaff of Lord Kitchener's advice to soldiers about their relations with women was, for those of us who remembered the whole of it, of rather doubtful propriety. A most delightful feature of the Sixth Scene (and I am glad to hear that it is to be extended) was a freak-film of an automobile perambulator, the work of that clever artist Mr. Lancelot Speed, author of the popular "Bully Boy" series. The scene of the Supper Club of the Receding Chins (where "one chin excludes") was a sound burlesque upon a certain phase of the modern Revue. Indeed, this imitation of vulgar banality was so close that the Pit mistook it for the real thing and were loud in their approval.

A "FINE CARELESS RAPTURE."

Miss Gaby Deslys as Rosy Rapture.

But the chief attraction of the play, both for a bewildered audience and, I suspect, for Sir James Barrie himself, was the bizarre collaboration between Miss Gaby Deslys and the author of The Little Minister. Her best friends could scarcely have been disappointed if she failed to impart any very noticeable refinement into the proceedings, but many must have been surprised to discover how well and with what in energy she could act. All the same, it would surely have been easy to find an actress who could have spoken the part at least as cleverly through the medium of an all-British accent. But perhaps it was just part of the scheme of burlesque that the two principal roles in an English Revue should be played by foreigners. However, the native element was admirably represented by Mr. Eric Lewis as a butler on terms of marked intimacy with his employers; by Mr. Leon Quartermaine as a villain with an awkward strain of hereditary virtue; and by Miss Gertrude Lang as a singer whose efforts were always being obliterated by the intervention of a fatuous Beauty Chorus.

Much of what may seem uncomplimentary in this first-night criticism will have lost its point by the time it appears in print. As is the way with Revues, there has, I hear, been a drastic overhauling of the original, and I anticipate many changes for the better.

But no change could add to the charm of Sir James Barrie's one-Act play, The New Word, which precedes his Revue. Here the author is at his very best (and not too sentimental) self; and Mr. O. B. Clarence as the middle-aged father, never on easy terms with his son, but now recognising a new relationship created by the War in which the boy is to play a part, gave a very fine performance; and Miss Helen Haye, as the mother, found, for once, a chance of showing her gentler gifts. I look forward to a still greater pleasure when I can read this delightful play in my private chair, and leave to my imagination those pauses and embarrassments which, when they occur on the stage―and they are of the essence of this dialogue between father and son―are apt to find a painful response in my own sympathetic nerves. O. S.

GLÜCKLICHE HAMPSTADT.

Nor bombs that drop on dome and steeple;

I sleep as safe as in Pekin,

For I am one of Hampstead's people.

The flower of all the Teuton nation,

The splendour of whose habitat

Beggars belief and beats Creation.

From menace of the German airman,

For if he drops his bombs on me

He'll pepper Heinrich, Hans and Hermann.

An Impending Apology?

Extract from a Lenten Card:―

"The preachers on Sunday mornings will have messages of great help and comfort to you, and at the Evening Services, except next Sunday when Mr. ——— will preach."

Here down the main street come hundreds more of those fresh, keen-faced boys who will be with you at the Front soon. 'Left―left―left―left―by the right―wheel! ' Not so bad after a few weeks' drilling, eh?"

Motor Cycling.

Not so bad, perhaps, for the men, but pretty bad for their officers.

Irish Sergeant (lecturing upon the rifle). "Now if ye'll listen and not intherrupt, I'll tell ye all about it―and if anny ay ye don't undershtand shtop me at onst."

OUR BOOKING-OFFICE.

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

In The Fabulists (Mills and Boon) Mr. Bernard Capes puts his practised pen to very much less effective use than usual. Some freak of mind or circumstance has betrayed him into a perverse experiment―the experiment of the too-short story of mystery. Of course in fiction notions of the very maddest may be made plausible for purposes of entertainment if there be sufficiently adroit preparation. An atmosphere must be created, a mood induced in the reader. Mr. Capes leaves these necessary things out and gives his shock in shorthand. Take "The White Hare." Modred shoots at a white hare and misses; simply can't understand it; assumes witchcraft; loads with a silver bullet; fires and kills; goes home to find his love dead. Later, his mother-in-law comes to die. "Cut the cursed thing out of me," says she. "What cursed thing?" says he. "Why, your silver bullet. 'Twas me you hit. I killed your girl to mislead you." So Modred with a howl of fury tore it out, and a white hare jumped through the window. Behold all! And it's typical. I have compressed the narrative slightly. Mr. Capes gives it a bare two pages and a-half, and the thing simply cannot be done so cheaply. These are indeed not short stories so much as skeleton notes for them. For so clever a writer The Fabulists seems rather a bad break.

The Minor Horrors of War (Smith, Elder) is an opportune little volume with very unexpected qualities. To quote the publishers, "these articles, which have appeared since the beginning of the war in The British Medical Journal, deal with various insect and other pests which cause disgust, discomfort, and often disease amongst our troops now fighting in all quarters of the globe." Very well then. Practical, you might say, and probably well worth the eighteen-pence of its price as a gift to somebody at the Front, but hardly a book to be read at home with pleasure and entertainment. There, however, you would be wrong. The writer, Dr. A. E. Shipley, F.R.S., has such a way with him that he can turn even the most unmentionable insects to favour and to pleasantry. For my own part his unexpected quips have kept me in chuckles. You recall Mr. Dombey's pronouncement―quoted here―that "Nature is on the whole a very respectable institution," which Dr. Shipley caps with the admission that there are, however, times when she presents herself in a form not to be talked about. I can hardly therefore indicate even the headings of his chapters. But I may, perhaps, take the one upon (if you will permit me) the flea as typical of the author's method. It contains a couple of quotations so pleasant that I cannot forbear to reproduce them. In one the indifference of the Turks to the attacks of this pest is explained by analogy from the words of the schoolboy who wrote: "A man with more than one wife is more willing to face death than if he only had one." The other is the plaint of a distinguished French lady: "Quant à moi, ce n'est pas la morsure, c'est la promenade!" I call that a very jolly way of discussing fleas.

Nora Bendelow was what one might call a rather unlucky girl. It is bad enough to come home from school for the Summer holidays and find that your brother has gambled away the ancestral home and drowned himself, leaving you penniless: but it is even worse when, having gone on the stage and got your chance as an understudy owing to the sudden illness of a principal, you bungle that chance and are then accused of having murdered the principal in question with arsenic. The only thing that kept Nora cheerful in the latter crisis was the fact that, flying to France on the morning after her dramatic failure and not having access to the London papers, she had no notion that she was a suspect. On the solid rock of this really novel idea, Mr. David Whitelaw has built up The Mystery of Enid Bellairs (Hodder and Stoughton), a melodrama which, if not full of thrills, is quite exciting enough to make a not too sophisticated reader finish it at a sitting. Stories of this kind are best expressed in terms of corpses. The Mystery of Enid Bellairs is a four-corpse melodrama, one drowning, two poisons, and a cliff-fall. The survivors of the massacre are the hero, the heroine, and the old lawyer. There is a novel feature in chapter one, where the hero strikes the villain on the chin instead of between the eyes; and later on in the book an invaluable hint for married men. If they have trouble in the home, all they have to do is to substitute arsenic for their helpmeet's morphia. If you doubt efficacy, try it first on yourself.

A Freelance in Kashmir (Smith, Elder) is an Indian historical romance of the later days of that time known as "the great Anarchy." Its author, Lieut.-Colonel G. F. MacMunn, D.S.O., has already shown, in The Armies of India, that if anyone knows the military history of the Eastern Empire he is that man. Of his qualities as a writer of romance I will not speak, lest I mislead you; for though the book is a good piece of work its interest is the jingle of spur and sabre, hard riding and fighting in battles long ago. The hero is one David Fraser, son of an Englishman and an Afghan woman, one of the gentlemen adventurers who controlled the armies of the Indian princes during the days before the coming of the Pax Britannica. This David had all kinds of adventures; at one time impersonating an absent ruler, after the right Zenda fashion; making love to, and naturally winning, a Princess; and generally thwarting the machinations of a dusky villain who, in the end, turns out to be none other than our old friend the Wandering Jew. A volume crowded, as you see, with incident. Some there will be in whom the atmosphere of it, the dust and heat and heroism, will awaken queer memories of the tales they read in childhood (With Clive in India was what I was recalling throughout). These will delight in it. Also of course Anglo-Indians, and all to whom the scenes of the book are already known. But, frankly, I would call it perhaps a little arid for the general; for those who require that Mars shall be properly subordinate to Venus in their romances. Still one never knows, in these days especially. I only throw out the hint as a warning to the light-minded.

I am a little perplexed as to the exact meaning of the title of Lady Charnwood's novel, The Full Price (Smith, Elder). Who paid the price, and for what? The theme of the story―a penniless girl taken up and educated by an elderly widower with a view to making her his second wife―is, if not strikingly new, at least handled in an original manner. And the central character, Lord Shelford, the widower, is as well observed as he is objectionable. A most unpleasant person in every way; so much so that it is a little hard to believe that even so persuasible a heroine as Margaret would have permitted herself to fall in with his views, especially with an obvious hero like Roger before her eyes as a contrast. Perhaps what snared Margaret's young imagination was the fact that Shelford was a Cabinet Minister and moved in every kind of exalted circle. If so, I can only hope that she was less disappointed than I was by the conversation that went on there. You see, the publishers had been at superfluous pains to tell me that the author's position made the political and social atmosphere of the book above suspicion. It says much for the interest of Lady Charnwood's tale that such a preliminary did not goad me into wholesale condemnation. As a matter of fact, while the atmosphere is entirely undistinguished, the character-drawing seems to me to be remarkably good. Eventually his lordship falls and breaks his neck; for which I could not but be sorry, since he was the most interesting person in the story. If he is a first creation the author of him will be well advised to go on and give us some more.

Very different inheritances fell to the heroine and hero of The Lady of the Reef (Hutchinson). To Bertha Crawford was bequeathed the solitary charge of a bibulous father, while Walter Massaroon found himself possessed of an estate in County Down, and journeyed from Paris, where he was a painter, to become a man of property in Ulster. Whether this sudden change of air and fortune affected Walter's head, or whether he was always as lacking in determination as he is here represented, is not mine to say, because I had no opportunity of making his acquaintance before the gods and a second cousin once removed had poured wealth into his lap. My feeling, however, is that he was born with at least one weak knee, and I feel aggrieved that he married Bertha, when the just reward for his mismanagement of his love-campaign should have been the heaviest of iron crosses. On the other hand, Bertha, in spite of Mr. Frankfort Moore's efforts to make her a super-angel, retains my most sympathetic admiration. Mr. Moore seems to find it as easy to write novels as I do to read them, but I am beginning to wonder whether this facility of his is not becoming dangerous. At any rate I think that he is showing symptoms of trying to promote rather cheap laughter, and it will be a thousand pities if so pleasant a writer allows his sense of humour fall from the high standard which hitherto it has so consistently maintained.

Member of Anarchist Society. "Gentlemen, I vish to resign!"

President. "Buy vy, brozzer? Vy vould you leave us?"

Member. "Ach! der iss no more glory in dis bomb business; eet iss becoming vulgar; everypody is doin' it!"