Punch/Volume 148/Issue 3860

FLAG DAY. THE PATRIOT'S PROGRESS.

The Tägliche Rundschau's message to the Kaiser is," Harden your heart!" More reinforced concrete?

⁂

The Archduke Eugene of Austria has assured his officers that they will spend Christmas in Venice and Milan. As a matter of fact, we understand, they will be sent further south.

⁂

Extract from an article in The Egyptian Mail describing the ceremony of Selamlik in Constantinople under the present Sultan:—"My last recollections of a Selamlik go back to the times of Abdul Hamid. How the scene has lost in splendour! Instead of the brilliant mass of gorgeously uninformed infantry and cavalry, a few hundred soldiers in khaki..." Still, less gorgeousness and more information probably mean an increase in efficiency.

⁂

The Chief Rabbi has announced his intention of going to France to visit Jewish soldiers serving there. He is also said to be anxious to investigate the report circulated by a misprinter that the men in the trenches burrow like rabbis.

⁂

A systematic study of the cracks in the buildings of the Tower of London is to be undertaken weekly for a period of twelve months, at the suggestion of the principal architect in charge of the Royal Palaces. It speaks well for the moral regeneration of our criminal classes in these days that several of our leading cracksmen are said to have offered their services for the good work.

⁂

Mouth-organs have so often made life impossible that we were glad to read last week that one had saved the life of a Canadian at the Front.

⁂

"Now," says Mr. Hilaire Belloc, "we know pretty accurately what the enemy's reserves of men are—at least of men at all useful for his purpose, and excluding the boys and middle-aged people whom popular journalism summons up to swell his figures." Our experience of the average middle-aged German is that he swells his own figure.

⁂

In a paragraph on the opening of the general angling season a contemporary reports, "Big barbel are jumping freely in the Thames." It is really very silly of these fish to be so nervy seeing that no enemy submarine has yet penetrated the river. Their confrères in the high seas must be greatly tickled.

⁂

A German machine gun and a trench mortar captured in France have been buried by the Army Council in the Museum of the Royal United Service Institution.

⁂

An interesting result of the rumour that the sale of lamb and veal is to be prohibited has been noticed by observant persons. Staid old sheep have been seen frisking about and cutting the most absurd capers, while elderly cows have been observed nuzzling yet older ones, in the hope that the butcher will not realise that they have grown up.

New Light on Magna Carta.

"Few people in Egham, no doubt, thought of Tuesday, June 15th, as the 700th anniversary of the signing of Magna Charta on the island of 'Runingmede,' between Windsor and Staines, which is in the parish of Egham. Many of us, however, have a notion of what that Charter meant to England and our forefathers, and it is well to remember the day. Seven hundred years ago one of the fickle Stewarts was met by that bold band of Barons.

Imagine the scene: King Charles is handed the document, and in the language of the day, politely but gently was he impressed with the need for such a Charter and advised probably that it would be all the better for his health if he signed it."—Surrey Herald.

It was on this occasion that King Charles, the well-known "Stewart," remarked (as recorded by Shakspeare):

No other speaker of my living actious

To keep my honour from corruption

Than such an honest chronicler.

"The Germans are now turning their attention to T.N.A.—tetra-nitro-aniline—an even more powerful explosive than the famous T.N.T. It is hinted, however, that we are not behindhand in regard to this point.

GET A BOX TO-DAY."

Yorkshire Evening Post.

This advice is not only dangerous but, in view of the needs of our soldiers at the Front, most unpatriotic, and should be unhesitatingly rejected.

Motto for Mr. D. A. Thomas, who is to be sent to the U.S. and Canada to discuss the question of munition contracts on the spot:—Bis D.A.T. qui cito D.A.T.

TO ONE WHO TAKES HIS EASE.

Of service done in this supreme of hours―

What sacrifice for England's sake you bear,

To what high use or humble put your powers!

If, pleading local duty's louder call

Or weight of years that checks the soaring wing,

You are excused the dearest gift of all,

What of the next best thing?

And so have some of your importunate friends;

From time to time you post them, when they press,

A little cheque for charitable ends;

You have reduced your tribute to the hunt,

Declined to bring the family to Town,

Discharged your second footman to the Front

And shut a tweeny down.

In that estate where he is set by Heaven,

You trouble less about your trousers' fit,

And eat six courses in the place of seven;

Upon your pint of champagne still you count,

But later drinks you temperately dock

(Because at clubs the alcoholic fount

Closes at ten o'clock).

For willing labour―watches of the night,

Shells to be filled, a turn of work to do

That sets a good man free to go and fight;

But tasks like these entail a lack of rest;

They put a strain on people's arms and backs;

And you've enough to bear with rents depressed

And all that super-tax.

If, sheltered close and snug, you shirk the blast,

Immune in idleness of hand and head,

False to your cause, disloyal to your caste,

When gallant men from yonder hell of flame

Come back awhile to heal the wounds of war,

And find you thus, you'll hear no word of blame,

But they will think the more.

UNWRITTEN LETTERS TO THE KAISER.

No. XXIV.

(From the German Ambassador at Washington, D.C., U.S.A.)

All-Highest Majesty,―I have carried out to the best of my ability the commands conveyed to me by von Jagow and Bethmann-Hollweg, which I have treated as coming from the most serene and in-the-topmost-degree infallible mouth of my most gracious Emperor himself, and I am grieved to report that the result so far has been nothing of the smallest value to the German cause. This is the more regrettable because I have spent an infinity of labour in counteracting the designs of the malevolent and in representing the acts and opinions of your Majesty in the best light that circumstances would permit. In these circumstances I include Dernburg, who is now happily removed from this country. He was, if I may venture to say so, a sore trial to me during his stay here, and I cannot rejoice sufficiently over his departure, tardy though it was.

I must tell you quite frankly that the sinking of the Lusitania, from which we all hoped so much, has not hitherto produced the anticipated results. Indeed, the American people, as you may judge from the newspapers which I send herewith for your Majesty's inspection, have shown and are still showing a most unreasonable and obstinate anger on the subject. The stories I have put about as to the ship's being armed they openly say they do not believe, and thus they make an unforgivable imputation against my good faith (which does not, of course, matter) and against the veracity of your most transparent Majesty, which is acknowledged by all Germans to be beyond reproach. Mr. Wilson, the President, has spoken to me on this matter with inexplicable feeling. "We cannot admit," he said, "that Germany has the right to destroy American citizens engaged in their lawful business, but we go further and declare that this atrocious act is against the laws of humanity, which even Germany is bound to respect." That was disagreeable, and I was compelled to use the utmost tact in continuing the conversation. I reminded the President that there were many American citizens of German race, who, in case of a difference between Germany and the United States, would undoubtedly range themselves on the side of Germany; but the President calmly replied that this remark showed that I had not properly understood the sentiments of American citizens, no matter what their race might be. "They are," he said, "American citizens first and all the time. Why," he continued, "you have only to consult the newspapers or attend gatherings of citizens to realise that those who are called German-Americans are at this moment tumbling over one another with the most genuine protestations of unswerving loyalty and devotion to America. If you build on these, and believe they will support the lawless acts of your Government, I can only assure you that you are profoundly mistaken." Somehow I felt that it was just possible that he was right in his estimate. It would be a melancholy disappointment to us, and I think with sorrow of all the money we have spent to such small purpose.

In the course of further conversation I happened to allude jocosely to the use of asphyxiating gas by our ever-victorious army, but the President took me up very sternly and said this was no laughing matter, but a shocking example of inhuman cruelty. I ventured to contest this opinion, declaring that death by such means was really in itself quite pleasant, whereupon Mr. Wilson asked me if I was anxious to choose it for myself and what would be the inscription on the tombstone. "You remind me," he said, "of the man who left directions in his will as to the disposal of his body in case he survived his own decease." What is one to do with such a man, who cannot appreciate the value to humanity of the epoch-making inventions of German chemistry? Our interview then ended, and I cannot say that it left me satisfied with the present attitude of the American Government and the American people. They are a stiff-necked lot, and are, no doubt, jealous of the triumphs of Germany in peace and war. At any rate, I cannot but feel that my stay here is not so useful as we had hoped; but it is no fault of mine. If people will mistrust your Majesty's intentions and show a malignant disposition, how is an Ambassador to deal with them?

Yours in all lowliness,

Von Bernstorff.

Age-Limit Again Extended.

"The Gordon Highlanders.―500 Men Wanted immediately. Duration of War. Age 19-400."―South Wales Echo.

"They had no use for compulsion or conscription. They would never bow their necks to the yolk of coercion."―Daily News.

Not even if the shell burst close to them?

IN THE EASTERN ARENA.

[It was the policy of the retiarius to retreat in order to gather his net together for a fresh cast.]

THE WATCH DOGS.

XXII.

My dear Charles,―Five days' leave for Henry. O beauteous prospect! Five whole days and nights of liberty and indiscipline, England and no ruins! Five fours are twenty, five twos are ten and two's twelve: a hundred-and-twenty glorious hours of crowded life with never a "Stand to arms!" Nobody shall inspect me or anything that is mine; I will inspect nobody and nothing. There shall be no barbed wire, no bully-beef tins anywhere. All around me shall be peaceful, refined, decadent, effeminate; silk socks, for instance, possibly of the mauve kind; the green squash hat, the patent leather shoe, even the umbrella. Shall I continue to carry all I possess upon my aching back? No; a taxicab shall carry me; and a messenger boy, following at a respectful distance, shall carry my gloves and evening paper. I will spend many of those precious hours watching real hot water gush out of a real tap, and I've a good mind to shave off my moustache for the time being.

There shall be no order or method in my comings and goings; I will saunter, possibly even slouch. Fair English women shall adorn the thoroughfares along which I pass; no coarse male hands shall tamper with my food; enamel ware and large grimy hands shall disappear; I will revel in white tablecloths, clean napkins, bright silver; in coffee and correspondence served on trays. "Spotless evening dress" and real beds shall reassert themselves in my life. The rising and setting of the sun shall be no concern of mine; at the former I will be sleeping, at the latter dining. I will be no man's master and no man shall be mine; my afternoon I will spend in the drawing-rooms of Mayfair, drinking delicate tea from frail china cups (with saucers to them, ye gods!) gossiping scandalously, or trifling flippantly with things that don't matter. I will wash me a hundred times a day; the Turkish Bath shall be my second home; sardines and all other things that inhabit tins shall be taboo; milk shall come straight from the cow and no Swiss middleman shall have had a hand in it; light in any degree required shall be had for the mere pressing of a button, and breakfast shall be at a reasonable hour.

Upon consideration, all other programmes are a wash-out; I will do nothing all the time.

Such are the orders I have issued to myself during this, the last tour in the trenches, before I go. My leave is in my pocket; my very ticket is in my cigarette-case. Life, these last days, has been one whirl of gay anticipation; I wait here for the relief to come. For the fourth time in four days the sun has returned to his accustomed west. "Lucky beggar," say I, a fellow-feeling making me wondrous kind.

In the telephone dug-out sits the signaller, quarreling with his confrère at the other end of the line, and repeating undeterred his spirited "Akk, akk, akk." Barbed wire in all fancy designs stands everywhere, patiently awaiting darkness so that it may emerge and join its kind outside the parapet. The senior captain sits in the mess hut struggling with reports and returns, certificates and lists of trench stores. The junior captain prowls as ever in search of the least untidiness in the demesne (what a curse he'll be to his wife when he goes on leave!). As usual the subalterns congregate and resettle European affairs and rearrange the end of the war for an early date. The latest rumour floats round the boys: "Turkey's hostility has given in; Austria's ammunition has given out; we are for home and light guard duties at Buckingham Palace this day fortnight." The inevitable slice of bacon frizzles over the brazier; breakfast in the trenches may begin at dawn, but it is not over by dusk. My pet irrepressible hurls threats at the enemy over the way; the answering bullet bespatters irritably the top line of our sand-bags. At his enplacement the sergeant of the machine gun section lays his aim for his customary twenty or thirty rounds at eventide, and explains for the hundredth time that the parts of the gun which recoil are technically known as the recoiling parts, the parts which don't recoil as the non-recoiling parts. His audience show their appreciation by gently humming songs about aged mothers and canteens.

To my happiness my servant puts the last touch with a cup of soup. "One of these days, William," say I, you will get a D.C.M." "D.C.M., Sir?" he queries. "A distinguished conduct medal," I say. "More likely, Sir," says he, "a district court-martial." My smile prompts William, ever a sympathetic subject, to gossip. Had I heard of the local parson? No. William gives me the facts. "He couldn't serve himself, Sir," says he, 'or said he couldn't, so he mounted his organist on his own best horse and despatched the pair of them, with his compliments, to the nearest Yeomanry Recruiting Office." A true raconteur, William pauses before making his point. "The Yeomanry people expressed their thanks, Sir," says he, "keeping the horse but returning the organist."

After all, the world is a good place, even this Flanders corner of it, and I have a smile of welcome even for the orderly who brings me from the Adjutant one of those familiar notes which wear such important envelopes but have usually such insignificant insides. I open it and read...

This is a true incident, Charles―they all are. I have been accused of making light of tragedy in these letters; in this case, however, I am only leading up to the horror of the thing. The contents of the note are: "Brigade message runs:―All leave cancelled, except in the case of those who have already gone. For your information." For my information!

It is past weeping for, a long way past swearing about. Things have never so suddenly become sordid and vile for me, especially the ubiquitous sandbags and chloride of lime. My temper is black; tinged with purple. I want to abuse somebody, hit him, kill him. The orderly, knowing the contents of the note, has gone. William, knowing me, has also withdrawn. I am about to help myself to two bombs from the trench stores, with a view to destroying my immediate surroundings, when my eye falls on the machine-gun, with its new belt in, all ready to fire. I advance upon it; the anger flashing from my eyes awes the section. With no man's leave or licence I sit down behind the gun and, raising the safety catch and depressing the button, I loose off without pause 250 passionate fiery rounds, meaning every one of them...

Amongst my fellows is a better-educated private who in civilian life is apparently a poet. His life also is at this moment one overwhelming burning grievance against things at large. His last day in the trenches has been one of that peculiarly offensive kind which, occurring in the life of every private at some time or other, consists of duty upon duty, task after task. His last straw is also a message just arrived: a verbal message from his platoon-sergeant to the effect that the first twenty-four hours of his rest will be spent on headquarters guard. Being either unaware of my presence or else aware of my inner feelings, he gives vent to verse, which, however little he may mean it or however emphatically it would have been suppressed by me in other circumstances, I now take a wicked delight in reproducing, without, of course, endorsing its sentiment:―

To make my life one long fatigue...

Oh, Gott strafe all the Powers that be,

From Sergeant Birch to the G.O.C."

Your dismal

Henry.

THE HORRORS OF WAR IN THE WEST-END.

New Club Waitress. "Looks quite tasty, don't it?"

COMMERCIAL MODESTY.

["In business affairs always understate rather than overstate your case. Moderation leads to conviction."―Sir George Riddell on "Philosophy in Business" in Success in Business and How to Win It.]

And spend the evening of your days in gentlemanly style,

Remember that the surest way of raking shekels in

Is to shun all overstatement as the chief commercial sin.

To insist upon the flavour and the richness of your food,

Far better tell your customers that, if it isn't nice,

It's cheap, it isn't nasty, and it's filling at the price.

Let the praises of your products be not arrogantly made;

And though your butter be the best that ever yet was seen

Describe it as "a substitute for high-class margarine."

Avoid exaggeration of the virtue of your weeds,

Confine your panegyrics to the statement that their match

Is not to be discovered on the finest cabbage-patch.

If you stated that in cut and fit you superseded P**l*.

No, it's better to be moderate in adjectives and nouns,

And say, "Our suits are equal to the choicest reach-me-downs."

In the realm of oratorio or the operatic line,

You'll never give the enemy occasion to rejoice

By claiming the possession of "a not unpleasing voice."

Described it as meiosis many centuries ago;

And the Greeks from long experience found no better way than this

To propitiate the vengeance of a watchful Nemesis.

And let your trumpet's note recall the gentle bleat of lambs;

"Come buy, come buy!" should be your cry, "but don't expect too much:"

Self-underestimation is the true commercial touch.

A correspondent observes that the telegraphic address of the Ministry of Munitions is "Explocoma, London," and hopes that the "coma" refers to the past and not to the present state of those who look after these commodities. We understand that the reference is to the future, and expresses Mr. Lloyd George's anticipations of the effect of his new shells upon the enemy.

"Achi Baba is described as a small 'Gibraltar,' and one officer remarked that the British soldiers were being asked to take positions which, if held by the British, would be unmistakable by anybody else."

Daily Sketch.

This is the sort of position that obviously ought to be "masked."

NO CHANGE

Tommy (to neighbour) "This is a bit of 'ard luck. 'Ere I've been invalided 'ome after two months in the trenches, and this is the bloomin outlook I've got!"

BLANCHE'S LETTERS.

The Changing of the Old Order of Things

Park Lane.

Dearest Daphne,―The sinking of all political differences, the fusion of parties, and all that sort of thing, is altogether splendid from one point of view, but, my dear, there's another side to the picture―the social side. I put it to you―how is Society to survive if we're all to be dear friends, not criticising anybody and not finding fault with anything? Life will lose all its snap, and Society may as well be wound up by the Lord Chancellor, or whoever it is winds up bankrupt concerns, and its goods sold for the benefit of its creditors. It's all very well to talk of the lion lying down with the lamb, but of course it makes life a distinctly duller business both for the lion and the lamb.

For instance, Mr. Arkwright and the Duke of Clackmannan have not only been prominent in opposite camps; their political hostility extended to their private life. It was the funniest thing to see them when they met at people's houses and had to speak! Stella Clackmannan, who simply adores the Duke, and Mary Arkwright, who thinks her husband easily the greatest man there's ever been, took sides with all their hearts, and enjoyed an almost perfect enmity. Oh, the dear little pinpricks and the innumerable small ruses de guerre that made their lives bright and snappy! Once, when it was Stella's turn to lecture at the Garden Talks of the Anti-Banalites, Mary Arkwright asked her what she was going to talk to us about; and Stella, who was dabbling in Oriental mysticism just then, said her subject was, "Which is the more desirable state of being―Nirvana, or the Final Negation of Moksha?" "Ah," said Mary, "then I read a meaning into that delightful frock of yours, duchess dear; the deep folded waistband is meant to suggest a lifebelt, as you're sure to get out of your depth!"

Stella got a bit of her own back the week after, however. You remember that marvellous boy, Popperitzky, who played the flute with his mouth and sang to it through his nose, and sent London quite wild? Mary Arkwright had secured him for one of her big affairs at their official home, and, while he was actually on his way to Upping Street, Stella had him kidnapped to Clackmannan House to play and sing to her crowd.

Clackmannan never opened his lips in public or private without attacking George Arkwright, and George Arkwright used to speak of the Duke as "a surviving relic of the monstrous and effete old feudal system," and now these two are colleagues in public and friends in private! The newly-created Minister for Remembering Things, with £5,000 a year and a seat in the Cabinet (the duties are to think of everything that other State Departments have forgotten) is no other than the Duke of Clackmannan, and he and George Arkwright are always conferring together and dining together! Stella C. and Mary A. have buried everything even remotely resembling a hatchet; they're for ever consulting about war-bazaars and matinées, and it's "Mary, dear, I meant to fix the 25th for my concert in aid of Wobbly Neutrals Who Can't Make Up Their Minds, but I thought I'd ask first if you want that date;' and it's "How very thoughtful of you, dearest! No, I've nothing at all for the 25th."

I saw them driving together in the Park yesterday, and as my car passed theirs I called out, "Hallo, Coalition; you both look rather dismal." "No wonder," Mary Arkwright called back; "each of us has lost her best enemy!"

People are whispering quite an amusing little storyette about Popsy, Lady Ramsgate, and the Alamode Theatre. The Alamode has long specialised in jeunes premiers; its leading men have always been acknowledged beauty-boys, postcard heroes and matinée idols. And of the whole series Lionel Lestrange (some people say his real name is Sam Hodges) was the biggest draw. His wavy hair, his eyebrows and his dazzling socks and smile were quite national property, and no jeune premier ever had half so many notes of admiration! Popsy, Lady R., and others of our frisky juvenile-antiques have always patronised the Alamode; indeed, Popsy has been so important there that the manager used to consult her about a new "find," and be guided by her verdict: for, as he once said, "What Popsy, Lady Ramsgate, says to-day about a young actor the matinée-girl will say to-morrow."

From the first she was quite éprise of Lionel Lestrange. Two or three times a week her curls and binoculars (the latter always at her eyes and always fixed on Lionel) might be seen in the Ramsgate box, and she grew so pointed in her attentions that it's said the rest of the company nicknamed Lestrange "The Dowager Earl!" And then one day, after thinking it over for about ten months, our postcard hero suddenly realised that his country was at war and wanted him, and he shed his bright socks and his stage smile and got into khaki. There was wailing and gnashing of teeth among the patronesses of the Alamode. But a successor soon bobbed up. "Mr. Claude Clitherow" was billed to play lead in Boys will be Boys, vice Lionel Lestrange gone to play a man's part elsewhere.

The first night went off well. The new star twinkled all right. The house was full, and innumerable feminine whispers went about, "What a darling Claude Clitherow is!" "Handsomer than Lionel Lestrange―or at least quite as handsome." Popsy, Lady R. sent for the manager in the interval, had the new boy presented to her, and took him out to supper after the show.

Shortly, however, there began to be rumours. And Popsy, who was completely off with the old love and on with the new, went flying off to see the manager of the Alamode one day in a flaming fury―"Have you dared play such a trick on the public, Morris Jacobson? I thought Claude Clitherow's face was somehow familiar to me! Yes, I see it's true!" "Hush, my lady," pleaded Jacobson, tearing his black ringlets in an agony; "don't give me away! I was at my wits' end! All our attractive young men are enlisting. Yes, it's true. Claude Clitherow is Daisy Bell of our chorus."

The Ramsgate box and almost all the other boxes at the Alamode are To Let now!

Ever thine,

Blanche.

"What ho, Charlie! Another little gasometer?"

AS BETWEEN TERRIERS.

Of course I still believe in him; I always shall; I can't help it; I'm his dog. But I must say that I find him lately just a little hard to understand. Other dogs' masters go out by themselves every day―leaving their dogs to amuse themselves as best they can. But my Master―ah! he was different. We were inseparable; roaming the country in the spring and summer; rowing on the river or loafing in the garden―Master trying to "brace himself for work," which he generally started by electric light about my bedtime. And in the winter we dozed together in the studio; or I stole chestnuts off the stove whilst Master smoked and whistled and forgot them. It was a perfect life. He called it "drawing for Punch." And then, about two months ago, he suddenly went wrong...

He came into the hall at lunch-time, after one of his rare visits to the City without me; said he'd got no further use for bowler hats, so stuck his on my head, and from inside it I heard him declaring how they'd "taken him at last―barnacles and all." The rest of that day he did nothing but talk about the "Linseed Lancers." I thought he might recover in the night, but the next day he went off to town again and came back dressed in four different shades of yellow and a puppy's drinking basin upon his head.

The third day, after a rather elaborate farewell, he again deserted me, and didn't come back. I waited for him at his bedroom door, knowing his ways of life and notions of bedtime. Later, I searched his studio―and the family gave me talk I couldn't understand. Two days, three days, still no Master. Then I went out to look for him.

It was late in the evening at the "Foaming Bowl" (a sort of lending library Master used to call at) that I was recognised and taken home; but black-and-tan terriers don't give in easily.

The family was very nice and sympathetic, so I wagged my tail to show them that I'd find him yet, and, O rats the very next day there was Master, back view, four shades of yellow and puppy's drinking basin all complete, walking ahead of me. I dashed after him, and landed in the old way, with my two front paws bang in the middle of his back. But it wasn't Master; and not even when I once sat upon a pen-and-ink sketch (wet) had I been called such names before. But still we don't give in, we black-and-tans. It didn't take me long to tumble to the fact that any one of yellow-brown suits walking the streets might possibly conceal my Master. I had to search them all.

The family got quite stuffy when I was brought home every night_by a different policeman. But still I persevered; until one day I suddenly encountered rows and rows of possible Masters marching down the High Street. I don't remember just how many I examined, but I do know that by the time the band was rearranged and the trams were able to go on again I had decided to give up looking for Master, and stay at home and wait.

*****

He came back. He comes back every other week now for an hour or so. Says he's a "terrier" himself and that I ought to be the Regimental Pet. But I'm afraid the post must be already filled, for I heard Master tell a man the other day that the R.A.M.C. Regimental Pet was a leech, specially trained to crawl at the head of the band, and salute by rearing up on its tail.

I wish that leech would get distemper.

"U29 sunk by H.M. ship———intimated sunk by Mr. Balfour June 9."―Glasgow News.

The new First Lord has quickly justified his appointment. Even Mr. Churchill never equalled this performance.

ON THE SPY-TRAIL.

VII.

A lot of people have told Jimmy that he ought to exhibit his bloodhound, Faithful, so Jimmy asked the milkman the proper way to send it to a show.

The milkman said it depended upon the kind of show, but in any case Jimmy would have to give warning first. He said he was going to see a friend of his who was a dog-fancier, and if Jimmy liked to bring Faithful he would take them with him in his milk carriage. Jimmy says they found the dog-fancier sitting fancying outside his house with a pot of beer. He was a very fat man, Jimmy says, and spoke with a husk. He thought a lot of Faithful when he saw him; he called his wife to have a look at him. He asked her if Faithful reminded her of anyone. She saw the likeness at once; it was her Uncle Joe.

"His side-whiskers to a T," the dog-fancier said.

The milkman told Jimmy afterwards that Uncle Joe was not very popular with them.

The dog-fancier looked hard at Faithful and asked Jimmy if he collected postage-stamps as well. But when Jimmy told him of the German spies that his bloodhound had tracked down he was so pleased that he wanted to do something for Faithful, and he decided to drink his health, when suddenly they heard old Faithful on the spy-trail again.

You see Faithful had discovered that when the back of the milkman's carriage is unfastened, it hits the road with a bang if you jump inside and push at it. Faithful is a good pusher, Jimmy says, and it made the milkman's horse jump three feet out of its sleep, and that jerked the back of the carriage up and banged it on the ground again. Jimmy says it made the dog-fancier and the milkman want to start off in a great hurry to go and see, good gracious, what it was, and the milkman started first because the dogfancier stopped to choke over his beer―it was the husk that did it, he said. By the time the milkman reached the road, Jimmy says his bloodhound had worked the milkman's horse up into a mad career.

Jimmy says he was afraid lest Faithful might get run over, and the milkman said he was afraid lest he mightn't. They were very hot on the trail, Jimmy says, and you could hear the back of the milk carriage flapping quite nicely against the road; it never missed once. Jimmy says the milkman had never seen his horse on the spy-trail before, and as he ran he told Jimmy in confidence that if he had known this would have happened he would not have come out, and Jimmy was to catch him doing it again, my word.

Jimmy says they had only run a mile when they came across some signs of Faithful's progress; it was a motorcar which had pushed its nose into a ditch, and the chauffeur showed the milkman how you did it. He said he had just avoided the milk-cart when a black rabbit suddenly bolted across the road and upset his nerve. Jimmy says bloodhounds are like that when they are on the trail; they appear inhuman, and it's because of their lust for blood. There were two ladies in the motor-car, and they asked the milkman to come back and help when he had caught his horse.

Jimmy says when they returned the chauffeur was under the car worrying; they could hear him doing it. They heard him tell the two ladies not to stand there like a couple of fools, but to——— and then the ladies started to cough violently, and the chauffeur mumbled something about asking for the coupling tools, and would the milkman help him for half-a-crown, because he had broken his petrol pipe?

The chauffeur was surprised to see Faithful; he crawled out to study his face. "I thought it was a black rabbit," he said, and then, because Faithful wagged his tail, he tried to strafe him with a spanner.

But Jimmy says Faithful knows all about spanners, he always has one eye fixed on things like that whatever else he may be doing with the other. Faithful liked to see the chauffeur hide himself under the car; he found him again quite easily, and then it was Faithful's turn to hide.

Jimmy says the milkman helped the chauffeur a good deal; he asked him what the petrol pipe was for, and wouldn't it do if he put a piece of cork in it, and what would happen if the motor-car started while he was like that. He told the chauffeur he had a cousin who was a blacksmith, but give him cows.

Jimmy says the milkman would have helped the chauffeur a lot more, but, when he pointed to the carburetter and asked if that was where they put the electric in, the chauffeur was very rude.

Jimmy says one of the ladies got a camp-stool out of the car, and when she sat down Jimmy says she stuck both of her feet out straight in front of her, and then hitched her dress to prevent it bagging at the knees, and then seemed to remember something, for she laughed. Jimmy says that when she saw him him looking at her she asked him if he would like sixpence, and then tried to find her dress pocket. Jimmy says he felt funny all inside whilst she was fumbling for her pocket, because he knew Faithful had done it again, and it was a spy dressed up like a woman.

Jimmy says he had to get over the hedge without being seen, and then he ran as hard as he could to ask the dog-fancier his opinion. Jimmy says the dog-fancier's opinion was two mastiffs, a double-barrelled gun and a policeman, and when they got back they found old Faithful playing at "all round the mulberry bush" with the chauffeur, who had mended his petrol pipe and was trying to lever the car out of the ditch.

Jimmy says the policeman warned them that anything they cared to say would be used as evidence, and then he had to ask the chauffeur to go more slowly, because he couldn't write shorthand.

Jimmy says it made the real lady sit down in the road and have some hysterics, and the chauffeur told her he didn't see anything to laugh at except the policeman's silly face.

Jimmy says the chauffeur looked at the mastiffs and asked the dog-fancier if he was going rabbiting; it made the milkman very happy, Jimmy says.

Jimmy says the man dressed up in woman's clothes turned out to be a spy who had escaped from a concentration camp, because they got some authorities who could swear at him. Jimmy says that when the magistrate heard that there was only one camp-stool, and that the German spy sat down on that himself, he said the real lady must be the German's wife, and it turned out he was quite right.

Jimmy says the chauffeur might have got off, but the milkman told how he had called the other two a couple of fools, and that proved they were friends.

Jimmy says old Faithful was pleased with himself that he wanted to wrestle both of the mastiffs catch-as-catch-can, and he kept daring them to come out of their collars at him until their necks began to look like hedgehogs.

Jimmy says Faithful sat up that night telling another dog all about it over the wireless telephone, until some one switched the other dog off.

From a tea-shop advertisement:―

"Our sanguinary expectations have been more than realized, and each day adds new admirers permanently as visitors."

Newcastle Daily Journal.

Under the distressing influence of the War even our most innocent traders seem to be out for blood.

HUMOURS OF A REMOUNT CAMP.

"How happy could I be with either."

MANUAL EXERCISES AND OTHER INCIDENTS.

We are a Rifle Brigade. Of course we haven't any real rifles nor are we really a brigade. But on account of our designation we do things differently from the common infantryman, and most of us do them differently from any kind of soldier.

For the purposes of our business of a Rifle Brigade we are possessed of a number of obsolete weapons, dating from the year 1870, nicknamed rifles. They are cold uncompanionable things, but, out of consideration for the feelings of the enthusiast who acquired them, we quite often take them about with us. Luckily there are more men than weapons and the laggards are compelled to parade without arms. Until the occasion to which I am about to refer I have always succeeded in being a laggard.

It happened just before Whitsuntide. The parade was unusually small and I was compelled to appear complete with rille. I admit that the thing made me nervous, but I dragged it forth with an assumed air of nonchalance and stood at ease with éclat. The Serjeant-major who was in charge of the parade suddenly barked at us, and from sheer fright I arrived at a position something resembling what I believe is technically known as "the order." In the pause that ensued I ascertained that my short ribs had only been contused and not broken by the end of the metal tubing.

"Shoulder-arms!" yelled the Serjeant-major. I really believe that I should have done that too if the metal projection called the foresight had not entangled itself in my coat. This made me late on the movement, and the Serjeant-major scowled at me. I was cross about it too because the piece of my coat which was hanging on the weapon was a material part of the garment. The movement not having been entirely satisfactory, we were directed to "order arms" again. I endeavoured to make up for my previous laxity by extra smartness, but misjudged the position of the little toe of my right foot. Its contact with the butt end of the rifle caused me to exclaim and I was severely reprimanded for talking in the ranks.

I confess that "Present arms!" had me beaten, but I did my best. I wriggled the weapon into what, as far as I could judge from a side-glance at my neighbour, was a correct position. But when the Sergeant-major's eye lit on me I had a feeling that all was not well. He strode silently but relentlessly in my direction. A person of less courage would have dropped the treacherous instrument and fled, but not I. Recalling the fact that I was an Englishman and a soldier, I tenaciously stood my ground. The Sergeant-major paused for a moment in front of me, and then he spake. I will say this for our Sergeant-major―he is thorough. I never remember a finer example of his thoroughness. When at length his breath failed him he sighed regretfully, and, with an air patient resignation, adjusted my hands into a strained position which seemed to cause him satisfaction.

I "sloped" the thing on the proper shoulder and got hold of the butt with the proper hand. One would have thought that this would have pleased even a sergeant major, but he was quite annoyed because I hadn't got the trigger business facing the way he liked.

"'Ow many drills 'ave you done, Sir?" Being no arithmetician I couldn't help him, and he looked suggestively at the recruit squad drilling in the corner. Then he bethought him that one fine day the hat would go round to provide a suitable gratuity for kindly sergeant-majors, and he only sighed again and passed on.

When next we were due to "order arms I tried to take a surreptitious look to find out where my toe might be, but the Sergeant-major at once made it clear that this was against the rules of the game. However, I missed my own toe all right, but the man next to me had to fall out. I was sorry about it, but if a man can't lose a little thing like a toe nail without all that fuss he isn't fit to be a soldier. Fortunately the Sergeant-major and I were agreed on that point, so the incident passed off without much unpleasantness.

As every soldier knows (and I learned that night), the incidents I have described are "manual exercises." Having done with them we passed into more congenial and familiar paths of drill, at which, when unhampered by a rifle, I am no worse than some of the others. Being a Rifle Brigade it is incumbent on us to march with the rifle at the "trail." Everyone knows that to get the rifle to the "trail" you give it a cant forward and seize it at the point of balance. Well, I missed it. This was due to the fact that the backsight bit out a large portion of my first finger. I admit that this caused some slight delay in the execution of a somewhat intricate manoeuvre. You cannot all in a moment pick up a rifle and replace a portion of your finger in an indifferent light. I explained to the Sergeant-major that if I had waited till the end of the parade to execute my repairs the pieces of my finger would have got cold and might not have amalgamated properly, and that the result might have been the loss of my services to the corps for quite a time.

If I had known that you cannot conveniently "right about turn" with a rifle at the "trail" the injury to my neighbour's knee would not have occurred. What he and the Serjeant-major said were both out of order. The man had no more right than I to talk in the ranks, and it wasn't the Serjeant-major's knee that was damaged.

Thenceforward until the end of the drill my neighbours gave me more room and I did better, but I can't say that I really got on friendly terms with that implement. Still, there was no sustained ill-feeling between the Sergeant-major and myself. After the fourth pint he gave me some private and confidential hints about the use of the rifle which, if he was right about them and I can remember, may come in handy.

OUR VOLUNTEERS

"My husband belongs to the Authors' Brigade. They're getting on splendidly―in fact, I believe they're going into a thir edition."

From "To-day's Diary" in The Daily Express, June 19th:―

"Mr. Bonar Law speaks at Shrewsbury School speech-day.

'Oh! Be Careful' (revival), Garrik Theatre, 8."

But a perusal of the Colonial Secretary's speech shows that there was really no cause for anxiety.

Lieutenant-Colonel ———, just posted to the Royal East Kent Mounted Rifles, was latterly serving with the 1st Reserve Regiment of Cavalry and is a retired major of the 5th Dragoon Guards. He has won many distinctions in the Soudan and South Africa, and was fatally wounded in the latter campaign."

Kentish Gazette.

Like Charles II. he seems to have been an unconscionable time in dying, but with more advantage to his country.

"The association of Admiral Sir Arthur Wilson with the Admiralty Bard is regarded here as a masterly move."―Rangoon Times.

Our congratulations to Sir Henry Newbolt.

THE NEW CAPITALIST.

British Workman. "COME ON, MATE. HERE GOES FOR A DOLLAR'S WORTH OF STAKE IN THE COUNTRY. EVERY LITTLE HELPS."

ESSENCE OF PARLIAMENT.

(Extracted from the Diary of Toby, M.P.)

House of Commons, Monday, June 21st.—When just now the new Chancellor of Exchequer walked up to Table carrying folded sheet of foolscap paper purporting to be copy of War Loan Bill, the hearty cheer that greeted him suggested that the nine hundred millions he had been talking about was to be divided among members of the House in addition to humble salary of £400 a year ruthlessly charged with income-tax. On the contrary, it meant that we and our constituents are, for purposes of the War, to provide colossal sum unheard of in the story of nations. What pleased the House was the clever construction of the scheme and the clear manner in which it was expounded.

It was McKenna's first appearance as Chancellor of Exchequer. Handicapped by succession to one of whom it might be said (omitting local allusion which supplies one of the most delightful non sequiturs in the language),

And he has chambers in the King's Bench Walks.

He did not attempt to compete with predecessor in those touches of genuine eloquence that from time to time uplift a prosaic business statements. Beginning without exordium he ended without peroration. Occupied only an hour in making clear as noonday to dullest apprehension a proposal equally prodigious and minute.

Whilst Prime Minister was still Chancellor, he emancipated Budget speech from thraldom of old tradition which, handed down from heyday of Disraeli and Gladstone, prolonged delivery over a minimum of two hours, with purple passages of sustained eloquence and the introduction of at least one quotation from Greek or Roman poet, which invariably drew emphatic cheer from classical scholars below the Gangway. This afternoon Asquith's favourite disciple, dealing with intricate financial subject, whilst equalling the licidity of the Master, even excelled him in severity and simplicity of style.

"Asquith's favourite disciple."

The speech punctuated with approving cheers, culminating in demonstration when, preliminary Resolutions by common consent passed through all its stages, the Bill based upon it was "brought in."

If House of Commons truly represents national feeling the War Loan will be a stupendous success.

Business done.—Bill read a first time, authorising raising of War Loan unlimited in amount. Understood that Chancellor of Exchequer, a man of moderate views, will be satisfied if nine hundred million sterling be forthcoming.

The Lord Hugh Query.

House of Lords, Tuesday.—House in rather awkward predicament to-day. Since his elevation to Woolsack the ex-Solicitor-General has found himself in invidious position. Though Lord Chancellor, permitted to preside over proceedings in what is sometimes called the Upper Chamber, he was not yet a peer. To-day, invested with peerage, Lord Buckmaster of Cheddington took the oath and was fully installed in office.

Proceedings attendant upon swearing in of new peer preserve quaint ceremonial going back to Stuart times. The novice, fully robed, is brought in by two noble lords also wearing the red gown of a blameless peerage. Having presented him to Lord Chancellor seated on Woolsack, to whom on bended knee he hands a roll of parchment engrossed with patent of his peerage, his sponsors lead him to Table and watch over him as he signs Roll of Parliament. Then Garter King-at-Arms appears on scene, clad in all his ancient panoply. By circuitous route he leads the way to back-bench below Gangway on Opposition side. What would happen to the British constitution if the group proceeded thither by shortest way Heaven only knows. Possible catastrophe is by Garter King's strategy sedulously avoided.

Arrived at their destination the new peer and his escort, at bidding of Garter King, seat themselves. At another signal, turning towards the Woolsack, they thrice salute it by gravely raising their cocked hats. The Lord Chancellor, who has also possessed himself of a cocked hat usually worn askew on top of full-bottomed wig, returns the salute. Thereupon the three red-gowned peers rise and, conducted part of the way by Garter King, quit the House by the door behind Woolsack, presently returning clothed in common-place twentieth-century garb.

To-day difficulty alluded to inevitably took place at stage of ceremonial where the new peer salutes the Lord Chancellor on the Woolsack. On historic occasion John Bright informed House of Commons that he "could not turn his back upon himself." Lord Chancellor seated on back bench below the Gangway could not render obeisance to himself simultaneously occupying the Woolsack. However there was the Woolsack, immemorial, immovable. Thrice the new Lord Chancellor with inflexible gravity saluted its august irresponsive presence and straightway proceeded to sit upon it.

Business done.—Commons, after brief conversation congratulatory of Chancellor of Exchequer, read War Loan Bill a second time. House of Commons, Wednesday.—In a speech occupying nearly two hours' delivery, unusual length in active war time, the Minister of Munitions explained his scheme of obtaining sufficient supply at earliest possible moment. Fairly full House recognised scope of plan and systematised vigour with which it is already set afoot. Only criticism offered is that it comes into existence ten months too late.

This, as Sark says, is the easiest form of criticism, pleasing to the critic as implying that had he been in charge of the business such prompt commencement would have been achieved.

Jack Pease, free from trammels of office and the pledge of secrecy that seals lips of Cabinet Ministers, made clean breast of the matter. Whilst benevolently "begging the House not to regard the new departure as reflection on the sins of the Secretary for War or the omissions of the late Government," he admitted that at beginning of the War "we had no idea" of what would be wanted in the way of munitions.

Arthur Markham, l'enfant terrible of debate, noting this admission, observed that there were a good many lamp-posts in Whitehall. Who deserved to be hanged on them he was not prepared to say. Incidentally, with an eye obviously fixed on a particular lamp-post, he asserted that "the cardinal mistake that Lord Kitchener made was that of concentrating in his own hands the work of the War Office, down to the smallest details."

Captain Guest, home on brief leave from the Front, his khaki uniform looking uncommonly fresh considering ten months' service, made simple eloquent appeal for more munitions.

Business done.—Lloyd George brought in Bill providing for increased supply of munitions. The Central European Powers are, he said, turning out 250,000 shells a day. "If we are in earnest," he added, amid loud cheers, "we can surpass that enormous production."

Thursday.—Sitting chiefly engaged in discussing Local Government Vote. Walter Long in moving it mentioned that twenty-nine years have elapsed since he first went to the Board. Returning to his early love finds her much changed.

In course of conversation, Hayes Fisher quite incidentally mentioned that next week a Bill will be introduced authorising a system of National Registration. Scanty audience greeted momentous statement with feeble cheer.

Business done.—Committee of Supply.

Persevering Volunteer (wrestling with bugle in remote spot). "Ah-h-h-h—got it at last!"

"The Government was investigating the cause of the great increase in the export of yarns to neutrals."—Egyptian Gazette.

"Wolff's Bureau," beware!

MY LADY'S GARDEN.

Was fair of old to see:

Here foxgloves grew of every hue,

The sweet, though lanky, pea,

The mignonette and pansy—

All blooms that smile or smell

With many a name, I own with shame,

I've never learned to spell.

In those dear days gone by;

It helped me drown the thought of town

And dull old care defy;

Amid its Summer fragrance

I'd sit out eve until

All earth was dumb save for the hum

From Philomela's bill.

Exhales an air of gloom,

A sombre green pervades the scene

Where blushed full many a bloom;

For oh! this former pleasaunce

On which I set such store

Is crammed with "veg." from edge to edge

To help her through the War.

"Wanted, a competent Madrasi Ayah to take charge of a baby of 10 months, who can speak English and Hindustani."

The Statesman.

This precocious infant should require some looking after.

Sergeant (instructing in the use of respirators). "Squad! In—hale! Ex—pire!"

AT THE PLAY.

"More."

At the Ambassadors Theatre (bijou) there is a sort of intimate gaiety lacking in the larger Halls of Revue. One is reminded of the Follies, but rather regretfully. For though the company gives you "odds and ends" of fun there is little enough either of wit or humour in the words. A duller monologue than that of The Author (represented by Mr. Morris Harvey) in search of an Idea can seldom have been composed; though Mr. Grattan disarms criticism by his frank admission of hopeless vacuity.

A parody of something stupid should not only be stupid itself, but should reproduce the particular stupidity of the original. And Mr. Grattan's burlesque revues fulfil admirably these requirements. A smaller man might have been tempted to import some alien element of cleverness; but Mr. Grattan avoids this snare. His imitations are a triumph of banality. The trouble always is in these cases that some of the audience will insist on enjoying the banality on its own merits, mistaking it for a product of creative art. This is very unfair to the author, yet I do not think that Mr. Grattan resents it. He does not even mind your being distracted from the excellence of his imitations by the rival claims of the ladies who interpret them.

Apart from these burlesques, to which the best of the humour was contributed by Mr. Leon Morton, and the precocious little Miss Betty Balfour, whose aplomb is superb (I wish there had been more of it), we had the usual clever imitations of actors' voices, done in the dark, though that did not help me to recognise Mr. Arthur Bourchier's vocal methods; and an excellent scene of an Italian restaurant, where Miss Iris Hoey illustrated the commanding superiority of her sex when it comes to a question of securing the attentions of a waiting staff. In justice to the male with whom she competed it should be said that his test took place in a British tea-shop.

There was also a pretty scene from the crinoline period, and yet another burlesque, of melodrama this time, not too subtle. A good deal of Miss Alice Delysia met the eye in most of the trifles that went to make up the evening's medley. Altogether we amused ourselves very passably, and indeed I blame myself for not having laughed more. O. S.

German efforts to recover Hell 1915 in front of Neuville have failed."—Daily Chronicle.

They were more successful in Belgium, 1914.

Ministerial Candour.

The Secretary to the Treasury the taxation of War-profits, as reported by The Daily Mail:—

"The delay was due to the desire of the Treasury to devise a scheme which would take in everybody."

"We are officially informed that the President of the Board of Agriculture and Fisheries has appointed a Departmental Committee to consider and repor wha seps should be be taken, by legislation or otherwise, for the sole purpose of maintining and, if possible, increasing, the present production of food in England and Wales."—Daily Chronicle.

The Committee evidently have to face a considerable shortage of "t."

"More than a thousand Germans were boycotted, following an abuse of the white flag."

Yorkshire Evening Post.

We have an idea that this apparently mild punishment was quite effective, and that these particular Germans will not offend again.

"Reconstruction will be of a most drastic description. Unionists have been offered half seats, but the Cabinet will probably be smaller and will be really a War Council as departments not connected with war will be executed."—Indian Daily Telegraph.

Mr. Asquith, happily, did not find it necessary to be so drastic as that.

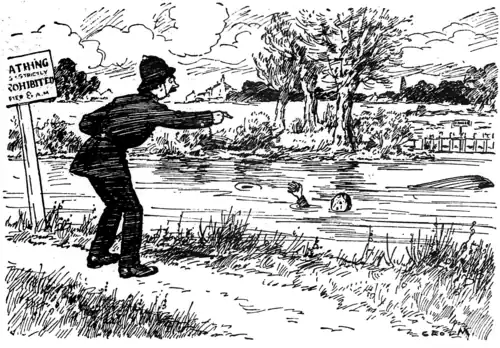

Rural Constable. "Now then, come out o' that. Bathing's not allowed 'ere after eight a.m.!"

The Face in the Water. "Excuse me, Sergeant, I'm not bathing; I'm only drowning."

OUR BOOKING-OFFICE.

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

It is pleasant to watch Mr. F. S. Oliver in Ordeal by Battle (Macmillan) hammering upon the noses of his and his friends' enemies, or gaily drawing the fangs of his particular black beast, the political lawyer, and to reflect on the charming appositeness of that honoured pseudonym Pacificus. But in truth one cannot jest about this profoundly serious book. Here is a writer who is abundantly justified by the result in breaking the silence of that loyalty which constrains even the most talkative and critical of us plain men a writer who can classify and summarise his political thinking in swift phrases which have the bite of epigram with a wit and precision Gallic rather than British. Yet not its wit or its lucidity but the fire and sincerity of it make this book. Of necessity hurried, it is neither hasty nor glib. Behind it lie the thoughts of strenuous years. There is anger in it, but not a mean or a cheap stroke. With more truth than such heroic simplifications usually possess he sets before us the German system as, essentially, the domination of that always baleful thing, the priesthood in politics—that is of the highly skilled and drilled "pedantocracy" with its irrevocable dogmas and surrender of all critical judgment; our own British scheme as, in effect, the creation of the dominant lawyer, not so much corrupt as corrupting; cognisant rather of precedents, ordinances, appearances than of realities; adroit in debate, hectoring in cross-examination; a seeker rather after verdicts than truth; hesitating in action; a man not of affairs but of aspects of affairs. Neither party is spared. Some distinguished personalities are faithfully dealt with. He pleads that we have been given (are being given) the stone of lawyerism when we hunger for the bread of leadership. He criticises with a welcome frankness the incredibly futile reticences, the unmeasured distrust of the people, the empty-smooth phrases of the politicals—such, for instance, as "the triumph of the voluntary system." If we win it will not have been any triumph of what may reasonably be denied the attribute "voluntary" and is most certainly not a "system." "The triumph of the voluntary system," said a French officer "is a German triumph; it is the ruin of Belgium and the devastation of France." Perhaps if there be any spleen in this book it is directed against those who not merely ridiculed but denounced the great soldier who warned them of this "calculated" war and the price of averting it. Do they make any amends, register any confession of mistaken judgment? Let me as one who humbly a fought in their camp and murmured their shibboleths answer regretfully for them. They do not. Mr. Oliver makes us see ourselves as we are seen. His book is a flame that will burn away much cant and rubbish; it will "light a candle which will not soon be put out."

It is not usual to notice books of verse in these limited columns, but the appearance of 1914 and Other Poems (Sidgwick and Jackson) seems an occasion on which a departure from this rule may fittingly be made. Of this little volume, which contains the last things written by Rupert Brooke, it can be said at once that no one who is cares for the heritage of our literature should omit to read and possess it. Inevitably from the circumstances in which the collection has been made it includes work of unequal value, some of which perhaps the poet himself might have wished to amend. But of the best of it, and especially the five already famous sonnets with which it opens, one can only repeat a criticism made upon their first appearance: they will rank for ever among the treasures of English poetry. Even to-day we can be grateful that the writer lived long enough to leave behind him a memorial of such dignified and noble beauty. Not that the book is all solemnity. No record of Rupert Brooke could forget his laughter; it sounds delightfully through the buoyant audacities of "The Fish's Heaven;" more gravely through "The Great Lover," where he tells over the list of pleasant things that have delighted him, much as Whitman might, but less laboriously. To generations unborn Rupert Brooke will become a tradition, another figure in the group of poets whom the gods loved and crowned with immortal youth. "The worst friend and enemy is but death," he wrote, facing with happy courage a fate of which he seemed to have fore-knowledge. To himself death may have come as a friend indeed, but to us as an enemy whom it is hard to forgive.

A long study of tales of crime and detection has led me to the proud conclusion that I am not easily to be baffled by their mysteries; so it is incumbent upon me to confess that Sir A. Conan Doyle, in The Valley of Fear (Smither, Elder), has fairly and squarely downed me. The first of his tales is called "The Tragedy of Birlstone," and here we have as rousing a sensation as the greediest of us could want, and Sherlock Holmes solving the problem in his most scientific manner. In the second tale, "The Scowrers," the scene of which is laid in America, we have the story of a society which devoted itself to murder and crime, and we discover why Mr. Douglas, a Sussex country gentleman, was concerned in the Birlstone Tragedy and was also a doomed man. "The Scowrers" is rather overcharged with bloodshed for my taste, but in spite of this I can only praise the skill with which a most complete surprise is prepared. Respectfully I take off my hat to Sir Arthur. In addition let me say that dear old Watson is actually allowed a short but brilliant innings, for I can imagine no finer achievement on his part than to score one off Sherlock, and this for a fleeting moment he is permitted to do. (Cheers.)

"The editing of King Edward VIII., in the series of the 'Arden Shakespeare,' published by Messrs. Methuen & Co., London, at 2s. 6d. net per volume, has been committed to Mr. C. Knox Pooler."—Scotsman.

Is not this perhaps a little previous?

THE INCORRIGIBLES IN HOSPITAL.

In the first bed on the left as you come into the ward was a red-haired trooper of five-and-twenty, with a cradle to keep the clothes off his wounded leg.

"Yes, Sir," he said to my greeting; "knee-cap for me, an' rather a mess of it. I haven't quite decided whether I'll have the leg off, or just go about with a stiff 'un. I'm leavin' that for the doctor. It's his funeral, after all, ain't it?"

"I hope it won't be a case of amputation," I said. Then, waving my arm vaguely, "And what is it like out there?"

"Firs'-rate, Sir! Firs'-rate, if it wasn' for those bloomin' allymets what they deals out for matches. When I got this bit o' shell in the knee it hurt me for a bit, but I soon got picked up, an' I was all right enough till the Red Cross chap says, 'A smoke?' 'Par demmy,' says I, knowin' a bit o' the lenguage. So what does he do but give me one o' them corporals, an' lights a sulphur allymet. That all but put my little light out, I'm tellin' yer. But I didn' let on, o' course, an' as soon as I got down to the Base Hospital I could get civilised wax vestas, so that was all right. But them allymets—they must ha' 'sphinxiated hundreds of our pore fellers, I give yer my word!"

I dispensed cigarettes of the peculiar kind that Tommy seems to love best, produced an illustrated paper, and after shaking hands went along to the next cot.

"Well," I said, "and how are you?"

"Oh, fair to middlin'. I was in luck's way right up to Noove Chapel, but after that the on'y jam we ever got was plum, an' you can get pretty tired o' plum jam if you 'ave enough of it, even without a bullet through the blessed 'ip."

"War's war," I remarked limply.

"That's right enough, Sir. But jam's jam, an' if Lord Kitchener knew the old reg'ment was restricted to plum jam—well, there'd be somebody's number up at daylight to-morrow, I bet! Some of the 'Ighland reg'ments was gettin' black currant, an' strawberry, an' damson, whereas we was pinned down to plum all the while. Mind, Sir, I don' mean' t' grouse, but 'ow anybody with any pertence to knowledge o' strategy an' ta'tics can expec' a man to fight 'is ugliest on plum jam—well, it can't be done, Sir! Otherwise you might say that this 'ere war is bein' conducted in a very businesslike fashion, an' K. can't look to everything 'imself, it's on'y fair to admit."

The next man's face was swathed in bandages. Only his eyes could be seen as I approached him, but there was an opening through which he could speak, though thickly.

"Oh, I'm all right, Sir!" he said. "I'm as right as rain now, though I'd ha' chosen some other kind o' knock-out if I'd 'ad the choice. You see, Sir, when I lef' Aldershot at th' beginnin' of August I was what you might call engaged to a young lady wot was in the saloon bar at one o' the best 'ouses in the command, and she'd made me promise 'er that I'd grow a moustache. Well, after about a week it stood straight out from my lip, and I says to myself, 'She'll find this inconvenient,' I says. So I took th' advice of our Colours, an' 'e told me that it was a case o' givin' it rope. 'It'll be all right, Clarke,' 'e says, 'if you let it go. After shavin' the lip for a few years the 'air always comes a bit stubborn-like, but if you let Nachure take its course, it'll smooth down an' lie flat, an' there you are.' He said, did Colours, that I had tons o' seed, and as soon as the crop got a decent length it would soften up an' be a credit to th' comp'ny.

"Well, when we gets over th' water, the first time I had a chance of lookin' at myself in a glass I sees that th' ol' moustache is doin' great. An', Sir, in five weeks it was a-curlin' round into proper formation, as you might say, an' I could twis' th' ends up, an' there wasn' one of our orficers what had a better kiss-me-quick nor what I had. So I writes home to my girl, tellin' her th' news, an' promisin' t' have my photo took at the firs' opportunity. You may laugh, Sir, but when a girl 'as set her heart on anythink like a moustache she'll have it, no matter what happens!"

"Well, I goes on with th' trainin' of it, an' I ain't ashamed t' say that there wasn' a better moustache in our Brigade! An' then, jus' as I'd about decided that I was prepared t' face the beautyscope, an' git a picture took, them bloomin' 'Uns enfiladed our line o' trenches one mornin', an' knocks me head over heels. That was nothink, as you might say; but, when the bearer-party picks me up, one of our drummers says, 'Your moustache 'as disappeared, Clarkey, ol' sport!'

"I puts my hand up to my mouth, what feels a bit soro an' cold, an' blow me if half my top lip ain't gone! My teeth was there all right enough, but half the lip had gone. Oh yes, they've patched it up all right, but they had to take a bit o' stuff off my shoulder to do it, an' nothink won't ever grow on that. At leas' that's what the R.A.M.C. officer said. Now ain't that enough to break a man's 'eart? Ain't it, Sir?"

I said that it was hard lines, but he might have lost worse than a moustache.

"I've no doubt you mean well, Sir, but you ain't married, I can see. You ain't nobody's 'usband. You ain't even nobody's fioncy! An arm or a leg, now—well, that's on'y a regrettable incident, as you might say, but to lose your only moustache, after all the trouble o' bringin' it up in the way it should go, after greasin' it with vaseline an' wipin' your mouth after ev'ry mouthful o' corfee, an' takin' care cv'ry time you lights a fag—why, I'd twice as soon 'ave 'ad my 'ead off, an' chance it!"

Everywhere the same story—grumbling (or, in their own charming argot, "grousin'") about trifles like a lost pipe, and making child's play of injuries little less than fatal. If you doubt my word, load yourself up with cigarettes, bar-chocolate, and illustrated papers, and turn into the first military hospital you find, and you shall understand why Mr. Punch was right in calling them "The Incorrigibles," God bless 'em!

By the way, talking of Mr. Punch, I think I must have seen him that day at the hospital. For I noticed He had a venerable gentleman with a hump at his back handing a book to one of the Red Cross nurses. He had a brave smile, though his mouth twitched a little, and I overheard him say, "This is a little present, my dear young lady, for your gallant patients; and I hope they'll find some of my love for them in its pages." And when he had gone I looked to see the name of the book; and it was Mr. Punch's

One Hundred and Forty-Eighth Volume.