Punch/Volume 148/Issue 3859

CHARIVARIA.

A gentleman writes to The Evening News to mention that it is impossible now to get paper collars, as they were of Austrian make. We had noticed lately many of the smartest men about Town wearing the linen article.

⁂

"I know no more subtly delicious sensation," says Mr. Ernest Newman, "than sitting in a hall full of people who dislike you." Oh, that the Kaiser would realise this, and come to Westminster Hall!

⁂

The Vossische Zeitung publishes a paragraph suggesting that Lord Haldane, when he visited Wetzlar, the Werther town, was acting as a spy. Whatever may be the failings of that rotund statesman, the ex-Lord Chancellor, we fancy that this is the first time that he has been accused of being slim.

⁂

Further revelations as to the underfeeding of prisoners in Germany are now to hand, and are openly reported by the Tägliche Rundschau. In the Zoological Gardens at Berlin, we are told, the Polar bear is now getting fish refuse instead of bread, the brown bears have to content themselves with roots and raw potatoes, while the cranes and other water birds have been deprived of their meat.

⁂

The author of Esther Waters has addressed a letter to the Press, on the subject of the food question, which has aroused the wildest indignation in canine circles, and angry dogs are now asking for Moore. The distinguished novelist, who estimates that there are in London "a million and a half of dogs, every one of which eats as much as a human being," has, it is declared, mistaken the dogs' ambition for their actual achievements. It is Man, the dogs retort, that is the greedy animal, and, if he could only be abolished, there would be no food question at all.

⁂

A German surgical journal says that a Prussian cavalry captain who was wounded in September has now resumed active service with an artificial leg. More remarkable than this, in our opinion, is that quite a number of Austrian officers are fighting with wooden heads.

⁂

There is said to be some alarm among the clients of the beauty doctor who was deported the other day lest the lady should retaliate by publishing a chatty volume of reminiscences about the triumphs of her art, with illustrations of some of her more remarkable restorations.

⁂

"To the north of Neuville we carried some German listening posts."—French official communiqué. So there's another illusion gone—the dear old simile, "As deaf as a post."

⁂

"This war," complained a flabby peace-promoter, "is an iniquitous war." Well, it is being prosecuted; what more can he want?

⁂

The Ottawa Free Press announces that Mrs. Polly Anne Strodes, who is seventy years of age and has been married thirteen times, has decided to seek a divorce from her present spouse. This would seem to confirm the belief that thirteen is an unlucky number, anyhow as regards husbands.

⁂

"RACING AND FOOTBALL SWEEPS."

Evening Standard.

While one may disapprove of those who during War-time have continued to take part in these sports, this language is surely stronger than the occasion warrants?

⁂

The French, The Evening Standard informed us the other day, have gained ground "on the heights which separate the valley of the Fecht from that of the Laugh." It is just as well that the Germans should realise that the Laugh is not always with them.

"Swat that Fly!"

(The "Willy" or Prussian Blue-bottle Fly.)

A Clever Disguise.

"Many Austro-German women dressed as ladies are infesting Northern Italy."

Australian Press.

More Apologies Impending.

"It is obvious that Mr. Lincoln cannot be trusted to tell the truth. His confessions testify to the efficiency of the Intelligence Departments of the War Office and the Admiralty."—Daily Chronicle.

More Commercial Candour.

Advertisement in a photographer's window:—

"Enlargements made. Faded ones guaranteed."

"Splendid manufacturing opportunity; only small amount of honey needed; must have good live man as partner."

News-Times (Denver).

No drone need apply.

Mr. Hillaire Belloc, in Land and Water, positively asserts that "the enemy consists in a certain group commonly called the Germanic powers." Ought these revelations, so helpful to the enemy, to be allowed? What is the Censor doing?

"The Hon. Secretary roported that the tender of Mr. H. Newton for panting at the hospital, of £36, had been accepted."

Northampton Chronicle.

Surely some of the patients could have done it cheaper.

"It looks to the new National Government to take all those steps which may be found necessary to weld the whole power of the nation into one mighty weapon with which to put an early fishing stroke to the war."

Western Morning News.

This new weapon must be some kind of rod—in pickle for the Kaiser.

From the paper that is ever first with the news:—

"Three years later, in July, 1915, Dr. ——— was strongly censured by a coroner's jury, &c."

Daily Mail, June 11, 1915.

"Colonel W. H. Walker (U ——— Widnes) asked whether the Board of Agriculture would communicate with county councils of districts where German prisoners are interned with the object of making arrangements for employment of pisoners for haymaking and other harvest help."—Manchester Guardian.

We trust the Government will not listen for a moment to this horrible suggestion.

The bronze horses of St. Mark, once probably on the Arch of Nero, and later on the Arch of Trojan."—The Field.

With the wooden horse of Troy playing so large a part in descriptions of the Dardanelles operations our contemporary's slip is intelligible.

OF GASES.

(To the enemy, who has given praise to Heaven for the gift of poison.)

Not such as cleanly chokes the breath,

But dealing, just for cruelty's sake,

A long-drawn agony worse than death;

Nor do you deem it odd

To vaunt its virtues as a gift from God.

(Although its humour seems remote);

They peg the patient's mouth and send

A soporific down his throat;

And, like a child at dawn,

Waking, he finds a stump or two withdrawn.

Gives you to deaden pain and fear;

They take and prize your jaws apart

When gaping wide for Munich beer,

Press-gag your mouth and nose,

And pump and pump till you are comatose.

Down your receptive maw you gulp,

Until the opiate seals your eyes

And Reason gets reduced to pulp;

So well the vapours work,

Like hashish on your torpid friend, the Turk.

Sore with a sense of something missed,

And want to know who drugged your brain,

I envy not the anæsthetist;

You'll raise a hideous rout

On finding all your wisdom-teeth are out.

O. S.

THE BOMBSTERS.

Billy was gravely occupied in splashing vivid colours on to the persons and dresses of fashion-plate ladies. To him came Dickie and watched the process with a supercilious air.

"Ladies don't have green cheeks," he remarked.

"Tired of pink," said Billy tersely.

"I've thought of a game," observed Dickie.

"I know: me be Germans an' you bay'net me with the sword what Uncle Ted gave you. Don't want to play."

"It isn't that; it's quite new."

Dickie drew nearer.

"Wouldn't you like to play at being a bomb, while I pretend to be a village?" he said persuasively.

"A English bomb?"

Dickie looked a little anxious.

"I meant you to be a German bomb, so as you wouldn't have to hurt me much," he admitted.

"You hurted me quite a lot with your sword," said Billy.

"Only pretence hurt."

"No, real hurt."

"Well, will you play?" urged Dickie, waiving that point. "You'll have to climb a tree to be a bomb."

Billy's eyes lit up.

"Why?" he asked.

"So's you can drop properly," explained his brother. "Come on."

Billy surrendered, and the two ran into the garden and made for the apple-tree.

"Who's to drop me?" asked Billy.

"Yourself will drop you, of course," Dickie replied with some impatience. "I'm a village. I can't be in the Zeppylin as well. The tree's the Zeppylin. First, you're the German soldier what throws you an' then you're the bomb."

"Can't I be English?"

"No; you might kill me, an' then what would mother say?"

"A village can't be killed."

"Well, but I'm everything in the village. The postman, an' the cocks an' hens, an' the doctor, an' they might be killed. At least, they might if you could aim straight, but, anyway, you can't be a English bomb, 'cos they aren't dropped 'cept where it's all right, you know. On forts an' things."

"You be a fort, then, an' I'll be a English soldier what can aim," persisted Billy.

"No, you mustn't. You've got to miss, an' bounce, or make a hole in a soft place," said Dickie, firmly. "Or you can be the village if you like, only I thought you'd like to be allowed to climb the tree first."

"All right, then. May I make a loud bang?"

"Yes, a very loud one, if you like."

So Dickie assisted his brother up the lower part of the tree, and then left him to scramble along a forked branch.

"Now you're a German in a Zeppylin, an' I'm the village," said Dickie, proceeding to walk about below, playing the doctor, the postman, cocks and hens, or a cottage, as the fancy seized him.

Suddenly there was a rending of twigs, and Billy was on the top of him. The impact was considerable, and they both rolled over. The bang was forgotten.

"You s-shouldn't have hit me," gasped Dickie, rubbing his head while indignant tears stood in his eyes.

"C-couldn't h-help it," sobbed Billy. "I wented by accident."

They sat looking at each other in the true enemy spirit for some time.

"I don't like this game," Billy sniffed resentfully.

"I'll be the bomb, then," decided Dickie, getting up on his feet. "You'll like the village better. There's so many things you can be, all at once.'

"I'll be a motor-car dashing through," said Billy, cheering up. "Lots of motor-cars, all dashing through, with men inside what have letters for Lord Kitchener."

"All right," agreed Dickie, pulling himself up into the Zeppelin.

Billy proceeded to dash through" with great vehemence and much snorting of engines.

"You sound like a train," remarked Dickie.

"Well, p'r'aps I am a train now," said Billy the versatile. "There's a station in my village."

Dickie hummed gently up aloft.

"I'm the Zeppylin making noisos," he said; then added with extraordinary courtesy: "Coming!"

And he did come, not forgetting to shout "Bang!" as he reached the ground, which was harder than he had expected. He also bit his tongue rather severely.

"You didn't bounce much," observed Billy, callously.

Dickie withheld his speech for several seconds.

Then he said, "I've had enough. Let's go in."

"No, I want to be a bomb again," pleaded Billy. "You see if I can't do it."

When their mother came out to fetch then in to tea, she was welcomed by two small ragamuffins owning between them four grazed knees, two pairs of scratched hands, a bumped forehead, a swelled lip, one whole pair of knickerbockers, and a couple of perfectly cheerful countenances.

"My dear children!" she exclaimed; "what have you been doing to yourselves? Oh, your knickers, Billy!"

"We've been bombs," they explained; "but it's difficult."

INJURED INNOCENCE.

Citizen of Karlsruhe. "HIMMEL! TO ATTACK A PEACEFUL TOWN SO FAR FROM THE THEATRE OF OPERATIONS! IT IS UNHEARD OF. WHAT DEVIL TAUGHT THEM THIS WICKEDNESS?"

[Airmen of the Allies have bombarded Karlsruhe, the headquarters of the 14th German Army Corps. The town contains an important arsenal and large chemical, engineering and railway works.]

HOW I CAUGHT EDWARD.

In tackling a trout that has evaded capture for a large number of years, the first thing to do is to find out what methods of fishing he has been brought up to, and then use care to avoid all of them. In such a case the fisherman's only chance is to fish all wrong. Accordingly the first thing I did when I engaged Edward, the famous Fraddingford trout, at the Two Vergers Hotel (they used to hire him out at a special extra charge of one shilling for the day) was to creep to the bank above his hole and try to fetch him a crack with the landing handle. As it happened, he observed me, and I missed him. I had no intention of maiming him, but it was important to do everything possible to lead Edward to suppose I had no intention of trying to catch him, and I knew that to attempt to slog him with the landing handle would put him off his guard.

Much more than this was however necessary. I tied a handkerchief to my rod so that Edward should think I was out flag-flapping with the boy scouts; and I sat on the edge and splashed my feet in the water, while from time to time I tore a sod from the bank and pitched it in. I saw a dog, and called him up and threw him in on top of Edward, and made him swim about a bit and bark, and in fact I did all I could think of to raise in Edward a false sense of security. In this I was successful; Edward was completely misled. So I caught him.

The flies I caught Edward with were five in number. "Five" because five were a great deal too many according to Edward's ideas; and not more than five because I was afraid of infringing the rule printed on his tickets, which said that he was only to be taken "by fair fishing with the artificial fly." It is difficult to say which fly caught Edward the most; each played a useful part in getting a purchase on him and so tangling the cast about him that his chance was hopeless; but my own favourite was the Green Wag-tail. I do not, however, overlook the part played by the hook. The fact that the hook is the most essential component of an artificial fly seems to be entirely ignored by most writers on fishing. A nice sharp hook is of course of first importance, but only experience can teach what patterns of hook a trout favours most under different conditions of light and temperature. Much knowledge, however, may be acquired by studying the old hooks which are to be found embedded in nearly all fish taken from popular waters.

While I am on the subject of trout-flies I should like to call attention to a fly which I have observed in hairdressers' shops on warm afternoons in the late summer. I have named this fly the Tickler, and in my opinion it would form a particularly deadly lure and should never be absent from any well-lined fly-book, for I am convinced that no trout would allow a fly of such pertinacity to remain at large.

In concluding this account of how I caught Edward, I should like to ask if any of your readers can tell me whether it is in any way possible to stuff a fish and eat it too. I may say that I am very fond of a nice fat fish, no one more so, and I feel besides that as a sportsman it is my duty to eat the fish I catch and admire its flavour. It comes hard, when one catches a big fish and wants him stuffed, to have to forgo the hearty meal of which the thought has nerved one's purpose throughout & long day.

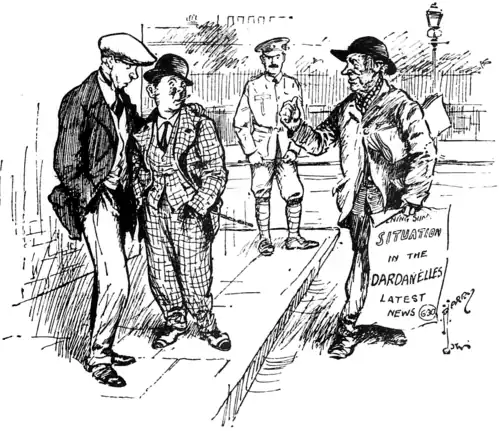

Facetious Slacker (as he notes wording on bill). "Any chawnce o' gettin' the job, guynor?"

Newspaper Seller. "No worry at all, mate. My secertary at the corner there'll sign ye on wivout any delay."

MOSES.

I must begin by affirming that this is a true story.

Everyone who ever idled in Paris in the good days when the world was happy must have passed now and again across the Gardens of the Tuileries and stopped to watch that engaging old gentleman, M. Pol, conversing with his friends the sparrows. Whether or no in these dark times M. Pol still carries on his gracious work of charming the birds I cannot say; he was looking very frail when last I saw him, a year and more ago; but that his influence still persists is proved by the extraordinary events which I am about to relate, and which, as I said before, and shall probably have to say again, are true. One must not claim too much for M. Pol or underrate the intelligence of Moses. None the less I feel strongly that, had it not been for M. Pol's many years of sympathetic intercourse with those gamins of the air, the Parisian sparrows, and all his success in building that most difficult of bridges―the one uniting bird and man―the deeds of Moses might never have come before the historian.

"Moses?" you say, "who is this Moses?" The question is a very proper one and it shall be answered.

Let us begin at the beginning. In the city of Paris, in an appartement not very distant from the Étoile or Place of the Arc de Triomphe dwell two little boys. They are American boys, and they have a French governess. In addition to this they are twins, but that has nothing to do with Moses. I relate the fact merely to save you the trouble of visualising each little boy separately. All that you need do is to imagine one and then double him.

Well, after their lessons are done these two little boys go for a walk with their governess in the Champs Elysées, or the Parc Monceau, or even into the Bois itself, wherever, in fact, the long-legged children of Paris take the air; and no doubt as they walk they put a thousand Ollendorffian questions to Mademoiselle, who has all her work cut out for her in answering, first on one side and then on the other. That has nothing to do with the story either, except in so far as it shows you the three together.

Well, on one morning in the Spring one of the little boys saw something tiny struggling in the gutter, and, dragging the others to it, he found that it was a young bird very near its end. The bird had probably fluttered from the nest too soon, and nothing but the arrival of the twins saved its life.

"Voilà un moineau!" said Mademoiselle, "moineau" being the French nation's odd way of saying sparrow; and the little creature was picked up and carried tenderly home; and since sparrows do not fall from the heavens every day to add interest to the life of small American boys in Paris this little bird had a royal time. A basket was converted into a cage for it and fitted with a perch, and food and drink were pressed upon it continually. It was indeed the basket that was the cause of the bird's name, for as one of the twins, who was a considerable Biblical scholar, very appositely remarked, "We ought to call it Moses because we took it out of the water and put it in a thing made of rushes." Moses thus gained his name and his place in the establishment; and every day he grew not only in vigour but in familiarity. After a little while he would hop on the twins' fingers; after that he proceeded to Mademoiselle's shoulder; and then he sat on the desk where the boys did their little lessons and played the very dickens with their assiduity.

In short Moses rapidly became the most important person in the house.

And then, after two or three weeks, the inevitable happened. Someone left a window open, and Moses, now an accomplished aviateur, flew away. All befriended birds do this sooner or later, but rarely do leave behind them such a state of grief and desolation behind them as Moses did. The light of the twins' life was extinguished, and even Mademoiselle, who, being an instructor of youth, knew the world and had gathered fortitude, was conscious of a blank.

So far, I am aware, this narrative has not taxed credulity. But now comes the turning point where you will require all your powers of belief. A week or so after their bereavement, as the twins and their governess were out for their walk, scanning, according to their new and perhaps only half-conscious habit, with eager glances every group of birds for their beloved renegade, one of them exclaimed, "Look, there's Moses!" To most of us one sparrow is exactly like another, but this little boy's eye, trained by affection, did not err, for Moses it truly was. There he was pecking away on the grass with three or four companions.

"Moses!" called the twins; "Moses!" called the governess, "Moses! Moses!" moving a little nearer and nearer all the time. And after a few moments' indecision, to their intense rapture Moses flew up and settled in his old place on Mademoiselle's shoulder and very willingly allowed himself to be held and carried home again.

And there he is to this day.

This is a free country (more or less) and anyone is at liberty to disbelieve my story and even to add that I am an Ananias of peculiar distinction, but the story is true none the less, and very pretty too, don't you think?

From a description of the New Derby:―

"The sky was a bright, burnished blue; everything was quivering in the heat; it was an ideal day for a picnic and all the people were pinkicking."―The Times.

It sounds a painful way of spending a holiday, and very bad for their boots.

"By the light of the moon I saw the door in the wall open gently and the heads of some of the albino women appear through the overture."

"The Holy Flower," by Rider Haggard.

Waiting to join in the chorus, we suppose.

"War map of German East Africa lithographed in Four Colours. This is the most reliable Map of German S.W. Africa ever offered for sale."―Advt. in "Cape Times."

This is a result, we suppose, of General Botha's success in altering the map in the latter region.

A NEW WAR-TIME CADDIE.

Player (two down at the turn). "I'm very much annoyed with you, caddie, for not watching my ball at the last hole. The loss of that ball means a very serious thing in a match of this kind."

New Caddie. "Don't you go worrying yourself about a little thing like that, Sir. Quite likely, in the course of our wandering over this ground, we shall come on another, and, mark you, a better, ball."

THE REST CURE.

And untrammelled arbitrator of all causes small or great,

With no shade of hesitation I would cheerfully proceed

To the prompt elimination of the Folk We Do Not Need.

I should not be so fanatic as to knock them on the head;

But, as quite the very best cure of the ills that we abhor,

I'd condemn them to a rest cure till the finish of the War.

Who are always busy slaying England's foemen with their jaw

Should no more be tolerated when they rave and rage and ramp,

But be speedily located in our Soporific Camp.

With the rancorous rhetoricians who exasperate the House,

And the candid friends of Britain who, whenever we have won,

Are invariably smitten with compassion for the Hun.

Foreign policy "controllers," pettifogging demagogues;

All the "copperheads" whose mission is to cavil and embroil,

And to crab the Coalition, since it halves the Party's spoil.

Who've usurped the critic's function; and, to cure their fell disease,

And to purge their souls' disquiet of the tyranny of tracts

I'd confine their mental diet to MacDonald's stream of facts.

Placed, to better our protection, safely under lock and key:

Alien enemies give trouble, yet it has to be confessed

We are menaced with a double danger in the native pest.

"It has been ascertained that the Kaiser visited Hartmannsweilerkopf in order to encourage the Guardsmen, and that after the stubborn resistance of the Germans by the Cameroons he retired to a high plateau in the centre of the colony and sat down."

Hong Kong Daily Press.

Further details of the Kaiser's movements from the same veracious authority are awaited with interest. Meanwhile we understand that his favourite song for the moment is "The March of the Cameroons Men."

"I met Mr. John Redmond in the outer lobby on Thursday and he looked terribly cross. What had upset him? By the way. I missed the familiar flower from his button-hole. He was wearing the small bow-tie which Mr. Balfour has made so familiar."

Weekly Dispatch.

But do not draw the hasty inference that Mr. Balfour had previously pinched Mr. Redmond's button-hole.

THE RECRUITING EYE.

The idea started with Mrs. Minter. Indeed, I think I may say that she is solely and entirely accountable for the business from beginning to end, and as several members of the Corps seem to think that someone ought to be made responsible I do say so. For I know that it will not trouble Mrs. Minter one little bit. She is the sort of woman who suggests things, starts them with enthusiasm, and then somehow forgets. She has a limpid conscience, a vivid eye, a way with her, and an abounding popularity.

"I think the Corps perfectly splendid," she declared after the inspection. "Only, oh, why don't hundreds more join?"

"They ought to," said Wright with conviction. "Or, at least, they ought to turn up stronger when they have joined. At Tuesday's drill, Platoon 6 was forming fours out of two men. It damps the enthusiasm of recruits when they find that they are practically the same in every formation."

Mrs. Minter flashed an appreciative musical-comedy smile, but I suspect that technicalities do not appeal to her.

"We are agreed, then," she said. "Now I have an idea. Listen."

Of course we listened. I don't think that I have mentioned Mrs. Minter's voice yet, but it has to be taken into account.

"It's just this. You can all have a most tremendous influence. You see, you're doing something. And so you can say to anyone, 'Why aren't you doing something too?' And you'll get no end of recruits."

It sounded beautifully simple; and Mrs. Minter looked simply beautiful. Carstairs voiced the general apprehension.

"It's a bit awkward, don't you see, Mrs. Minter. We don't actually know what another fellow may be doing. Of course with fellows one really knows it's different. But generally speaking it's a bit awkward, don't you see?"

Carstairs may not be a stylist, but we felt that the argument was sound.

"I've thought that all out," said the lady airily. "That's really just what my idea gets over. You don't say anything. You just look. It could be made most tremendously effective. You are marching along the road, don't you see, doing your bits, and standing watching you as you pass are heaps and heaps of slackers who ought to be either with you or, if they are eligible, in the army. You don't say anything, but as you pass you just look. You can put a most frightful lot into a look if you really try. You must be surprised and hurt and incredulous and disappointed and reproachful and―yes, just a teeny bit appealing, and here and there one of you catching someone's eye and then turning away quickly as though it was really too much, and a few friendly and encouraging, and some quite too saddened to do anything but march bravely on. It would be ever so much more fetching than the thrilliest poster if it were properly done."

"It would want a bit of doing," said Bowring moodily. Bowring is a left guide and saw where he would be in it.

"Naturally it would need arranging, but I will help you all I can. The great thing is to get the right kind of expression for the right kind of face. Now, Mr. Beeching, for instance..."

You think we jibbed, but then, of course, you don't know Mrs. Minter. She impartially distributed expressions suited to our faces. I will say nothing of myself except that for show purposes there is a tendency to encourage me to become an even number in the front rank. But, as Mrs. Minter remarked, grim determination can be as artistically portrayed as any of the subtler shades of emotion. She was very nice about it.

A couple of days later we had a route march. Owing to a rather late change in orders, while a few men brought their rifles and turned up in uniform, the great majority did not. Still we were pleased with the day. We put up a great tramp, including Murber Bridge, Little Chimpington, Brookleigh and Sturton Much―villages in which a volunteer corps is something of a novelty, I should imagine, by the way the natives turned out. It was an opportunity, and loyally we responded to Mrs. Minter's instructions. We flattered ourselves that a recruiting sergeant following our line would have had an easy thing that day, and we openly regretted that we should never know the actual result of our effort. We were mistaken.

I dropped in to see Wrathby yesterday―he is our Quartermaster. There were half-a-dozen other people there, all strangers to me, and one or two of them, I found, strangers to the Wrathbys also. A placid old lady was achieving momentary importance by some narration when a word caught my ear―

"It was quite a sensation for Little Chimpington..."

"Little Chimpington!" I exclaimed.

"Mrs. Gapper lives there," explained the lady who had brought her.

"Sensation" sounded promising. What is termed a dénouement was evidently impending. I made sure of the alignment of my tie.

"I was speaking of a gang of those terrible German spies who were marched through the village recently," explained Mrs. Gapper for my benefit. "It is a mercy that the Government is interning them at last, for a more desperate type of men one could not imagine. Fortunately they were kept well under control by a few of our own soldiers, who marched by their sides with leaded rifles; but the glances that the prisoners cast in our direction as they were hurried by showed us plainly, now the masks were off, what we might expect at their hands."

"When was this?" I found myself asking huskily.

"Last Saturday―only last Saturday. I can see their faces yet. Such looks of malice, vindictiveness, brutal cunning, hopeless despair and baffled treachery I feel that I shall never be able to forget."

"You are quite sure that they were Germans?" asked her friends. "There seems to have been a doubt."

"My dear! With faces like that what else could they have been? Besides, they were branded!"

"Branded!" It was Wrathby's voice, shrunk to a whisper. He also had heard and been drawn into the dénouement.

"Yes; everyone had to war a wide red band round his arm with the letters A.E.D.C.―Alien Enemy Detention Camp, of course."

***

There is a motion down for the next meeting of the Committee of the A———ton Emergency Defence Corps to substitute for the existing brassard one of the more conventional type. It is understood that it will be carried unanimously.

The Ideal Lodger

"Wanted, superior Furnished Apartments, good neighbourhood, for Gentleman who gets all his meals out, sleeps out, pays for his washing, and calls once a week to settle his account."―Hull Daily Mail.

"A girl―quite a pretty girl, dark eyed, dark haired, high coloured, with anxious violet-blue eyes―came softly in."―The Penny Magazine.

Most of us only possess one pair, and it seems needlessly extravagant to use so many eyes at once. Why not save the violet-blue ones for Sunday?

From a parish magazine:―

"We regret to say that the Church gates, which have been on our mind for some time, have finally fallen to pieces."

Well, that ought to relieve the pressure a little.

THE LITTLE INCONVENIENCES OF WAR.

A FIELD DAY WITH OUR VOLUNTEERS.

Officer (who has not lunched). "Now, Sir, you've got to stand here and keep a sharp look-out all over the country. But you're on no account to see the enemy till half-past two."

THE WOODS OF FRANCE.

Midsummer, 1915.

The old-time songs of Arcady that ran

Down the Lycæan glades; the joyous ring

Of satyr dancers call away their clan;

Not this year follow on the ripened Spring

The Summer pipes of Pan.

When the loud legions rushing in array,

The flying bullet and the cannon roar,

Scatter the Forest Folk in pale dismay

To hie them far from their green dancing floor

And wait a happier day.

To this old haunt, when friend has vanquished foe,

They will return anon with lightsome tread

And labour that this place they love and know,

All broken now and bruised, may raise its head

And still in beauty grow.

In the green English woods down Henley way,

In meadows where the tall cathedrals chime,

Or watching from the white St. Margaret's Bay,

Or North among the heather hills that climb

Above the Tweed and Tay.

Take heart and smite their enemy, the Hun,

Who knows not Arcady, by whom the dance

Of fauns is scattered, at whose deeds the sun

Hides in despair; strike boldly and perchance

The work will soon be done.

The comfort of quiet places; in the din

Of battle you shall hear the murmuring

Of the home winds and waters; there will win

Through to your hearts the word, "Still Pan is king;

His Midsummer is in."

A Little Learning.

"A Wozzleite's 'Neugma.'―Apropos of our recent 'Turnover' by 'A Wozzleite' a correspondent writes: Lest any of your readers should need a bit of hustling as regards their 'Humanities,' I may point out that there is a pretty instance of what grammarians call 'Neugma' in what 'A Wozzleite' wrote about Mr. Johnson: 'The Secretary was Mr. Johnson, our organist, who is always ready to accompany anything, from "God Save the King" to the young ladies home from the choral class.'

'Neugma' is when one meaning of a word is made to accompany another meaning. It is a playful practice indulged in by Virgil (Aen vi., 680, 682, and 683), and very frequently by Thomas Hood and Captain Basil Hood."―The Globe.

It seems to us that the correspondent and the printer between them have rather over hustled the Humanities. Zeugma we know, and also Syllepsis, but what is "Neugma"?

THE RETURN OF ULYSSES.

[M. Venezelos has been returned at the head of a party commanding an overwhelming majority.]

ESSENCE OF PARLIAMENT.

(Extracted from the Diary of Toby, M.P.)

House of Commons, Monday, 14th of June.— With ordinary course of legislation blocked this Session there has been so little work to do that House has met only three days a week. Arrangement highly popular with country Members, who, with Monday thrown into usual week-end recess, are enabled to see something of their families at home. Variation arranged for this week. Second Reading of Budget Bill put down for to-day. This one of the events of a Session. On such occasions Chancellor of Exchequer is accustomed to deliver important speech leading to extended debate. To-day Members with one accord put aside private engagements; hurried down to House in anticipation of important discussion.

Occasion chanced to find that eminent traveller, Columbus Vasco da Gama Magellan Joseph Walton, Bt. in Scotland. Had prepared elaborate and convincing speech upon Chancellor of Exchequer's financial proposals. Situation embarrassed by reason of restricted train service north of the Tweed on the Sabbath-day. Chinese Walton, as he is called for short, not the man to be beaten by trivial obstacle like that. By organisation of motor-cars making connection with train bound South arrived in town early this morning.

Got down to House in good time to secure corner-seat immediately behind Treasury Bench, a favourable position for delivery of epoch-making speech. As soon as Questions were over, Chancellor of Exchequer, with characteristic modesty seated low down on Bench, picked up his despatch-box and passed on to seat opposite brassbound box usually occupied by Minister in charge of current debate.

Orders of day called on, Speaker recited first on list.

"Finance (No. 2) Bill; Second Reading."

Then a strange thing happened. Reminiscent of historic fight between the Earl of Chatham and Sir Richard Strahan. McKenna, having been privily informed of intention of Member for Barnsley to make a speech, sat waiting for Chinese Walton. Chinese Walton, longing to be at him, sat waiting for Chancellor of Exchequer. Meanwhile the Speaker, above all things a man of business, observing that no one rose to open debate, put the Question, declared it carried in the affirmative, and the Budget Bill for 1915, involving unparalleled expenditure, passed its critical stage without a word spoken.

Business done.—Budget Bill read a second time. House adjourned after an hour's sitting.

Reginald Atlas McKenna

The Record Cash Lifter.

Tuesday.—House crowded in every part in expectation of speech from Prime Minister on moving new (the fifth) Vote of Credit. Anticipation more than realised on highest level. Expecting one speech Members charmed with two. Remarkable by contrast in conception and style. The first evidently carefully prepared. When greeted by hearty cheer that testified to enjoyment of full sympathy of the House, later acknowledged—"to me a source of strength and a stimulus to more efficient performance of arduous duties"—Premier laid on box a sheaf of notes. Frequently referred to them during speech that did not occupy more than half-an-hour. In no degree embarrassed by the tie. A blind man listening would not have known that he had provided himself with assistance of notes.

The second speech, in its way quite distinct, was necessarily delivered on spur of moment. It arose upon brief debate following harangue by Dalziel, who in absence of organised Opposition is making close study of the Candid Friend. Premier adroitly seized opportunity, not designedly provided, to make two happy hits. A little difficulty about appointment to Irish Lord Chancellorship at one time threatened rupture with Irish Nationalists. This afternoon, John Dillon, whilst reserving to his Party the right to criticise the new Ministry on its merits, declared they would always be controlled by honest and sincere desire to aid it in carrying the War to a triumphant issue. With grateful acknowledgment the Premier tactfully sealed this pledge, part in expectation of speech "given on behalf of the Irish Party by one who has for many years been one of its most distinguished leaders and spokesmen."

Another difficulty arose upon appointment of ex-General Carson to the Attorney-Generalship. Naturally resented by Home Rulers, of whom he was the most dangerous opponent. Premier now disclosed the fact that when the post was first offered Carson declined it, tardily yielding to strong pressure put upon him.

General impression that these two speeches have effectually dispelled cloud of dislike, displayed chiefly on Liberal benches, that gathered round Coalition Government. Its position in the House and the country distinctly strengthened.

A MARESFIELD NEST.

Discovery of valuable cattle at Maresfield Park by Mr. Ronald M'Neill.

The M'Neill (not Swift, but Ronald) still on the war-path, hunting after German princes and barons who have during times of peace and amity possessed themselves of residential estates in this country. Here, for example, is Prince Münster, late of Maresfield Park, Sussex, Aide-de-Camp to the Kaiser, now at the Front assisting in

gassing his former hosts and neighbours. M'Neill wants to know whether this property, with a valuable herd of cattle in the park, is preserved intact for the enemy owner, or whether its conveniences and resources are being utilized for war purposes?

Home Secretary, whose guileless appearance, remarkable in an Attorney-General, gave added point to his remark, said that the Public Trustee, who is administering these things in the national interest, informed him that there is no such herd of valuable cattle in the park as pictured by the fond fancy of The M'Neill.

"There are," he added, "four cows of the ordinary kind, and they are doing their utmost for the benefit of British subjects."

Business done.―Vote of Credit for 250 million agreed to without murmur.

Wednesday.―In debate on Vote of Credit Under-Secretary for War by remarkable statement added to mystery that broods over supply of Munitions of War. "There have," he said, been no cases of shortage of high explosive bombs since February. At present moment there is an ample supply with ample reserve."

Business done.―Vote of Credit passed Report Stage. Budget Bill nearly through Committee.

House of Lords, Thursday.―Lord Newton is a precious asset. Is accustomed at intervals too widely separated to enliven dull debate by sparkling speech, the brilliancy of its flashes of humour intensified by stony solemnity of countenance. A sound Party man, sure to be found in right Lobby when division in progress, he does not hesitate upon due occasion to gird at noble Lords on his own side, even though they be seated on one or other of the Front Benches.

Lansdowne never openly resented this freedom. Bided his time for making the retort courteous. It came with opportunity of nominating members of his following to a share of offices in Coalition Government.

He made Lord Newton Paymaster-General.

The little joke, excellent in conception, has its lamentable aspect, since henceforward the candid critic, seated on Ministerial Bench, will find himself tongue-tied. Pith of joke lies in circumstance that whilst Newton is dignified by name and office of Paymaster-General, suggesting lavish distribution of unlimited financial resources, he himself remains without a salary. By one of the incongruities of the British constitution the Paymaster-General is himself unpaid.

Possibly in extreme development of Communistic principles shewn in the pooling of Ministerial salaries the forlorn condition of the Paymaster-General may not have been overlooked. If anything has been done it is by voluntary contribution, not by State provision.

Business done.―Lloyd George reappearing on Treasury Bench in new guise as Minister of Munitions loudly cheered from both sides. Progress in Committee with Civil Service Votes.

Love's Captives.

"A pretty local wedding was solemnised at ——— Parish Church yesterday.... Later Mr. and Mrs. ——— left for Cardiff en route for the Devonshire coast. Prisoners of War."

Pembroke County Guardian.

All, of course, is fair in Love and War, and this similarity may have led to a confusion between them on the part of the compositor.

Corrections to Indian Army Regulations, Medical, recently issued:―

"Para 17, page 5, line 17, add the following:―

An engagement is also terminated by the marriage of a lady nurse."

This putting of an end to betrothal is among the many regrettable effects of wedlock.

Ex-Policeman (finding Germans hiding in wood.) "Now then―pass along there, pass along!"

A BERLIN PROBLEM.

Wife. "Otto, where are we going for our holidays this Summer?"

Otto. "Well―er―there's Turkey."

AT THE FRONT.

It is hard for the most insensible of men to look on at this war unmoved for long. We have looked on at it for months and months and months from a haunt of ancient peace known for some obscure antiquarian reason as a firing line; and now we are to be moved; to-morrow, or the next day, or, to sum up all the possibilities in the word of the historic despatch, "shortly." Indeed, the Sergeant-Major even now approaching with his indestructible smile may bear the details that we are to follow. The Sergeant-Major is a great man for a detail. Nothing escapes him. Three weeks ago measles stole into our midst like thieves in the night. The S.-M. had them before could you say "Bosch."

Pending the push off, we anti-asphyxiate ourselves. There used to be some doubt among N.C.O.'s supervising as to whether the impedimenta supplied for that end were inspirators or perspirators. Eventually they compromised on "gas-bags." Only nine patterns have so far been issued, but the more cautious of us wear all these simultaneously, so if Nos. 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9 fail, 2, 4, 6 and 8 may prove efficacious.

Preparations for the trek are in train. Each Platoon Commander―in view of the fact that men who have lived nine months in ditches may have mislaid the use of their feet―has written out slips permitting No. 000 Private Blank to fall out and report at Dash with all possible expedition. Now Mr. Mactavish is a very thorough officer, and he was determined that no one was going to catch him out through his having too few of these backsliding permits. But when I found him engaged on the sixty-fourth, the strength of his platoon being forty-seven, I felt compelled to demand some explanation. He seems to have assumed that some men might fall out twice. To me, the assumption that men whose feet have given way will pick up a taxi somewhere and overhaul you just for the pleasure of falling out again, appeared rash.

Since the foregoing was indelibled, we have walked a great walk―seven leagues, no less. At intervals, we bivouac in odd bits of Europe that happen to be unoccupied when we stumble on them. Some are crowded with horrible dangers. Never shall I forget seeing Private Packer wake up from his afternoon sleep to find himself practically in the act of being bitten by a ferocious cow. Springing up, with he threw the officers' kettle at the savage ruminant; whereas by all the best traditions he should have continued to smile. Fortunately the cow (like President Wilson) was too proud to fight.

The trek has been a great disappointment to those who were looking forward to writing home brave accounts of "how I marched forty miles on a biscuit and a cough-lozenge?" When we got to our first bivouac three of us had just made a frugal meal of malted milk tablets and melted barley sugar when the Mess-Sergeant loomed up with the news that lunch was served. My appetite was so impoverished by previous indulgence that I gave up after the third course. But the coffee and cigars were admirable.

We are now billeted in a wood. The billets make excellent fuel, and there are no wild animals except beetles, which, though large and highly coloured, appear quite pacific. The glow-worms glow of an evening and help out the embers of the moribund fires, which are strictly doomed to die with the daylight. Round these embers Mr. Atkins stands in groups and renders with every variety of modulation and idiosyncracy, but with united cheerfulness, his famous patriotic number, "I want to go home." The stars are in their heaven and Mr. Atkins is not downhearted.

AT THE PLAY.

"The Green Flag."

SAPPING THE GARDEN OF EDEN.

Lady MilverdaleMiss Constance Collier.

Lady BrandrethMiss Kyrle Bellew.

If one is permitted to judge of a man by the kind of woman he attracts, the character of Lord Milverdale (or Peter, for short) is an interesting enigma. For some reason best known to himself (like most of the obscurities in a play it happened before the curtain rose) he had married a rich and spiteful vulgarian. On the other hand, for his second love he had selected in Janet Grierson a woman of exceptional sweetness and refinement. The domestic complications which followed upon the discovery of this diversion of his affections compelled him to withdraw to America, and it was from there that he wrote to Janet, inviting her (with cable-form enclosed) to join him by the next liner. Naturally one was intrigued about the personality of a man for whose heart there was competition between two such opposite types, and it was very regrettable that a respect for the dramatic unities prevented Mr. Keble Howard from gratifying our curiosity by letting Peter appear on the stage.

In his unavoidable absence, Lady Milverdale relentlessly pursued her husband's lover, and would have been well content to break up the happy home of another couple―Sir Hugh and Lady Brandreth, friends of both parties―if by sowing unwarrantable suspicions against her rival she could have got her revenge. You will gather that our sympathies were not encouraged to take the side of morality, and that the injured woman had no chance with us as against the disturber of her peace. But Mr. Arthur Bourchier would never have lent himself to the defeat of virtue in however repellent a guise, and in the person of Sir Hugh Brandreth, K.C., after using his forensic gifts to dissuade Janet from joining her lover, he succeeds in finding a passable solution of things, though he never exactly readjusts our disordered emotions.

The degeneration of comedy into farce is a frequent subject of critical attack; but here it was the farcical element that revived us. The First Act had gone rather tamely, and in the opening of the Second some of us only listened to Mr. Bourchier's sound homilies on the after-effects of lawless elopement with the respectful toleration due to the accepted generalities of common experience. It was then that the arrival of Lady Milverdale in Brandreth's chambers, hot on the track of Janet, gave opportunities for a game of hide-and-seek, in which, after some diverting acrobacy, the huntress is tracked down by her quarry. And so they play was saved.

It was a charming irony that assigned to Miss Lilian Braithwaite, of all unlikely people, the part of serpent in the original Paradise of the Milverdales. For myself I made no attempt to believe that a wrong thought could ever have found accommodation in her nice head. To hear her urging, with that gentle voice of hers, the desirability of breaking the seventh commandment was to listen to an innocent child pleading for the right play with its favourite toy. The fact―deplorable, if you like―is that Miss Braithwaite was never meant to be anything but her charming self, though within those limits her moods can vary all right, as in the startling change by which she totally forgets her tragedy in the sudden joy of scoring off the other woman. This thankless part was played with sacrificial devotion by Miss Constance Collier, who to the odious qualities of a scandalmonger was asked to add the ridiculous affectation of a woman who had climbed into a world to which she did not belong. Her ignorance of the proprieties went so far that she called at her husband's club for his letters; and the strange thing was that the hall-porter obliged her. At which of Mr. Keble Howard's fashionable clubs is this kind of outrage permitted?

A MIDSUMMER DAY'S DREAM.

Mr. Bourchier (Sir Hugh Brandreth) in full peace-paint.

Mr. Bourchier was excellent in the little that he had to do; but it was almost too easy for him. As for Miss Kyrle Bellew, who played Lady Brandreth, her angularity will wear off with time and teaching; but she must try to dress for the part she plays, having no need to advertise her native piquancy. Miss Barbara Gott, as a garrulous housekeeper, kept the First Act alive, and Miss May Whitty, as a mother and an afterthought, was useful in the Third Act, to which her natural ease of manner brought a refreshing air of probability.

The title of the play, The Green Flag, had nothing to do with the Nationalists, and implied no competition with the Union Jack. It was a symbol taken from the railway, and was waved by the K.C. as a caution to Janet.

Mr. Keble Howard has not committed a masterpiece. His titled people smack a little of that Suburbia in which he has specialised. But the play should have a decent run for the sake of the farcical business of the Second Act.

O. S.

P.S. I regret that in a recent notice of Armageddon I did Mr. Martin Harvey an injustice in attributing to him the unfortunate change in the Scene where Joan of Arc was made to address the English general, and not, as in the original text, the French General. Mr. Stephen Phillips writes to inform me that he himself suggested this alteration during rehearsal.

"Mr. and Mrs. Ponsonby."

Surely, you would not let your wife come between us!" says the lovely but naughty Mrs. Chesterton to the infatuated Jim Ponsonby in Mr. Walter Hackett's new farcical comedy. The remark is typical of the spirit of the play. There are only seven characters, and six of them are at one time or another engaged in pronounced flirtations with somebody else's spouse. I wonder if Williams, the Ponsonbys' solemn-faced butler (Mr. Edward Duggie), was able to keep track of the amorous permutations and combinations in which his master and mistress were involved in the course of three Acts. My own recollections of the plot are somewhat hazy―perhaps because I laughed so much―but I remember that Jim Ponsonby, in order to find time to make love to Mrs. Chesterton, accused his wife of flirting with Dick Trevor; and that Mrs. Jim, though quite innocent of any such intention, was gradually converted to a belief that she was really in love with Dick. The principal agent in this conversion was her disreputable papa, Horatio Billington, who assured her that "the Billingtons are all like that," and proceeded to illustrate the family failing by inviting Mrs. Chesterton to a tête-à-téte supper. On his advice, too, Jim, in order to arouse his wife's jealousy and so to recover her affections, makes violent love to Mrs. Trevor. That brings Dick to his bearings, and eventually leads to a restoration of the status quo all round.

Played by an inferior company I can imagine this kaleidoscopic study in conjugal frailty being absurd and unpleasant. Handled as it is by the accomplished performers at the Comedy Theatre it is wholly unobjectionable, and goes with unchecked brightness and zest. As the husband-lovers―the one a mixture of priggishness and excitability, the other by turns forward and lethargic―Mr. Kenneth Douglas and Mr. Sam Southern are well suited; while Mr. Fred Kerr plays the elderly roué with easy certainty. Miss Lydia Bilbrooke looks very handsome as the fascinating Mrs. Chesterton. The chief burden of the piece falls on the plump shoulders of Miss Marion Lorne, who sustains it admirably as Mrs. Ponsonby. A slight American accent gave additional point to her lines, while her varied facial expression would make her fortune as a film-actress.

L.

The 500th performance of that delightful play, Potash and Perlmutter, at the Queen's Theatre on the 24th, will be a matinée, of which the entire receipts are to be devoted to the funds of the Blinded Soldiers' and Sailors' Hostel, St. Dunstan's, Regent's Park.

"The Hand that Rocks the Cradle."

"In Bangalore one 6 H. P. A. C. Sociable Cycle Car, in good order till lately driven by a lady."―The Madras Mail.

"I don't 'old with this 'ere vaccination, Mrs. Green. What's vaccination done for my little Tommy? Since I 'ad 'im done 'e's 'ad whooping-cough, chicken-pox, measles―in fact, everythink but small-pox!"

THE KHAKI WEDDING

At wedding routs, when peace was rifer;

The bridegroom played a thankless part,

He seemed the merest cipher;

But khaki's now the only cry

Where once the lady filled the eye.

No costly veil, no sheath of lilies,

No orange blossoms, less and less

Of silk and satin "frillies";

She dresses on a modest plan

To leave him every chance she can.

Best fits a sacrificial altar;

Her man to-morrow joins the fray,

And yet she does not falter;

Simple her gown, but still we see

The bride in all her bravery.

"Situation Mousekeeper or good Plain Cook, age 48; good reference; now disengaged."

Portsmouth Evening News.

Nothing doing. So few people want a menial who keeps mice.

"Mr. Milton Rosmer... has also had hopes of reviving 'She Stoops to Conquer,' but it is as difficult to play Sheridan in a theatre as it is to play Mozart in an opera house, such very special art being required."

Pall Mall Gazette.

But why turn down Goldsmith?

"Mohamed Khalil, who is incarcerated in the prison of the Native Court of Appeal, is reported to be viewing things in a spirit of stoic bravado. He asked for a barber yesterday morning while he has sent out to purchase bootlaces and a collar stud."

The Sudan Herald.

Ah, but wait until the collar-stud rolls under the chest-of-drawers. That will take the bravado out of him.

THE ENCOUNTER.

This is not my story. It was related to me by Hattersley, who is a dog-owner and a dog-elevator. That is to say, he elevates dogs to a superhuman position, which, in my opinion, they are not qualified to occupy. I'm all for dogs, so long as they are kept in their proper places, in a kennel or a stable or something of that kind; but Hattersley has them everywhere―on beds and chairs and sofas. He spends part of his time in teaching them elementary tricks with biscuits or lumps of sugar, and takes up the rest by giving long accounts of their extraordinary sagacity in detecting character. Dogs and children, he says, are like that. They always know in one sniff who likes them and take their measures accordingly. However, I didn't mean to set out all Hattersley's theories on dogs, but to let him tell one of his dog stories. When you've heard it you'll know what kind of man he is. So here goes, in Hattersley's words as nearly as I can remember them:―

"There's only one weak point," said Hattersley, "about dogs, and that is their insistence on being taken for walks. You can't fob them off with a stroll in the garden. If you try, they lie down and refuse to follow you and display no interest whatever in your proceedings. They will go outside the grounds. I can't take my pack of three Pekinese and one Great Dane out on our country roads on account of the Dane's capacity for sudden pouncing on other dogs. He means no harm, poor beast, but he disconcerts and angers other dog-owners, especially ladies, and if the other dogs resent his pounces he naturally fights. It is a point of honour with him. Besides, the Pekinese either stroll defiantly along the crown of the road, thus interrupting all traffic and giving occasion for violent language from motor-cars, or they push their investigation into the nature of grass-tufts to such a point of prolonged particularity that they get left far behind and have to be retrieved and carried after shouts and whistles have been spent on them in vain. These things being so, I have, in the matter of dog-walks, concentrated on a path along the bank of a river, where there is no traffic of wheels, and where on most days other pedestrians and other dogs are so few as to be scarcely noticeable. Here I exercised my dogs until I came to have a sense of private ownership over this particular walk.

"So things went on quite comfortably for some time. But one morning I chanced to walk along my sacred path meditating I know not what trifles and entirely absorbed in them. The Pekinese were following their own devices. The Dane was pacing by my side, and my hand was fortunately on his collar, when I felt a sudden tension and looked up. A hundred yards away, but coming towards me, my startled eyes beheld a tall military-looking lady conducting, at the end of a strong lead, a massive and monstrous bulldog. At the same moment she saw me and we both stopped. I failed to restrain the Pekinese; they made a combined rush and were all round the advancing bulldog in a moment. He did not seem to be aware of their existence, but with eyes glaring fearfully and with foaming mouth he was straining at his lead in a violent endeavour to get at Hamlet, who, on his side, seemed to be consumed with an equal fury. I must mention that Hamlet has a special distaste for bulldogs. In early life, before he came to me, he had lived on intimate terms with a dog of that breed. He consoled himself for that temporary friendship by trying to massacre every bulldog he met. The situation was serious, for we were on a narrow path which at this point was bounded on one side by the river, on the other by a row of willows and a wide ditch.

"'This,' shouted the lady, 'is terrible.'

"'It is,' I said, 'highly inconvenient.'

"'My dog,' she said, 'is most good-natured with little dogs, but he always flies at big dogs, and he can't bear Danes.'

"'Hamlet,' I said, is just like that. He detests bulldogs.'

"'If you wouldn't mind going into the ditch,' she said, 'we might get past.'

"I feel that the situation is worthy of one of Mr. Belloc's battle-plans; but I have no skill in these, and must ask you to imagine the features of the ground and the movements of two commanders whose ardent desire was not to collide but to avoid one another. Both of us were all but tugged over, but at length we accomplished our manoeuvres and got past, and after reciprocal apologies we were able to resume our walks, the Pekinese being with immense difficulty persuaded to abandon their new playfellow.

"We met again on the following two mornings, but in a more open patch of country, where the lady was able to fetch a wide circuit in a meadow. She cowered down in the grass three hundred yards away until the danger was over; but the Pekinese of course tracked her down and seemed determined to plunge down the throat of her animated canine gargoyle. Obviously this sort of thing couldn't go on. On the fourth morning we met again on the confined path. This time Hamlet gave a wrench, the bulldog made à bound, and in a lightning-flash the two were rushing at one another's throats. The lady averted her eyes, I held my breath, and in anticipation I beheld us collecting the tattered remnants of what had once been dogs. Crash! They met; but, instead of setting to work to devour one another, they began to gambol round, to yap with pleasure, to pursue one another in short circles and altogether to give the liveliest signs of joy. The relief was extraordinary. The apprehensive lady raised her head. 'They must have known one another,' she said; and indeed it was so. We discovered that these were the very two dogs who had spent their childhood together. They had known it all the time, and had strained and panted for reunion while we strove to keep them apart. I assure you dogs are better and more intelligent than men. After that we could meet without fear."

That is Hattersley's story. For my own part I don't quite see why he makes such a point of it. What strikes me is this, that Hattersley, who has known dogs all his life, thought they were purple with passion, when as a matter of fact they were wild with joy.

IN A GOOD CAUSE.

The Italian Blue Cross Fund of the Rome Society for the Protection of Animals is in great need of funds for the establishment of hospitals for horses wounded in the War, for the provision of veterinary surgeons and the supply of ambulances and drugs. This is the first appeal that Mr. Punch has made for our new Allies, and he hopes that some of his readers will kindly send gifts in aid to Mrs. Graham-Harrison, 36, Sloane Gardens, S.W.

"Sociable young fellow required to go half-shares in season's expenses in fully equipped river camp, age about 25 to 30, good thing for someone suitable."―Advt. in "Daily Mail."

There are several other camps ready to welcome sociable young fellows of this age; "good thing for someone suitable."

Alone they did it.

Extract from Battalion Orders, Tipperary, June 17th:—

"To-morrow being the Centenary of the Battle of Waterloo, in which the R. Innis. Furs. was the only Regiment that took part, the afternoon will be observed as a half-holiday by the Brigade."

Sergeant (to recruit wandering about at the will of his horse). "'Ere, you! What are you doin' there, ridin' up an' down like a general?"

OUR BOOKING-OFFICE.

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

In The Soul of the War (Heinemann) Mr. Philip Gibbs writes with that sympathy, perception and distinction which by diligent use of his deft and careful pen he has trained us to expect. He is at his worst in such passages as "I went out to aid them but did not like the psychology of this street, where death was teasing the footsteps of men, yapping at their heels." Red, whether of flags or trousers, is never mere red to him, but always "blood-red." And he lets himself be decoyed into patches of irrelevant purple—tiresome snares of his trade. "Heavens!" you seen to hear him say, "if this agony of war, this tragic blend of heroism and bestial savagery is not to move a man to eloquence will anything ever on God's earth?" And yet despite this reasonable plea it remains true that he is at his best where most direct and artless, and that there is some faint lapse from taste in fine writing about such infinitely poignant realities. That said, one can praise unreservedly both the matter and spirit of this book. And indeed both make such criticism seem rather too frigidly academic. Mr. Gibbs does not write as the complacent journalist reporting unique "stories." He gives both sides of his picture, the expected and the other: the courage and resource of men and the high glory of battle, the nausea and despairing depression, the occasional failure of the shattered spirit, the insurgent brutality, the haunting perplexity that shadows even the stoutest and most inspiring patriotism—"Why kill—or be killed—by men against whom I have (or had) no possible quarrel?" Passionately he wants us others never to us these dreadfully futile things happen again, and invites us to share the blame for a system which makes it possible. And this without assuming that there is anything else to be done now but bring a murderous group to justice, or without failing to recognise that to have yielded to the menaces of their power and insolence would have been a worse thing for the world than even the horrors it has found. It is not a book for the faint-hearted or the empty-headed—if there be any such left. The others should read it for its truth, its sincerity and the candour of its criticism.

If, as I suspect, Hyssop (Constable) is a first novel, it contains ample promise to make me expect considerable things from Mr. M. T. H. Sadler in the future. I say this because, while the present volume is agreeable enough—though the plot, which only develops in the final chapters, is grim and hardly for everybody's reading—it is obvious that the author is as yet by no means fully master of his art. As with many young writers, his power of observation has somewhat intoxicated him; detail, he has yet to learn, is for the novelist a good servant that can easily become a tyrant. For example, Mr. Sadler has remembered and recorded practically everything about the life of a modern Oxford undergraduate; but though the result is a wonderfully faithful presentation, it might well provoke impatience in those who have no personal associations to help the interest of the picture. It is too like a bound volume of The Isis. Through four-fifths of the book he records minutely the characters and trivial actions of Philip Murray and his undergraduate friends in order to prepare the effect of the one big event at the end. Occasionally, circumstance poignant has given to some of this detail an unexpectedly value. I found myself arrested, for example, by the skill with which a foreign railway station at night had been caught, with "the whistle of the pneumatic breaks as the express comes to halt above the low platforms; one of the sounds that seem to echo now out of the happy unrecoverable years." Occasionally the detail is simply superfluous. "Philip left his hat and stick in the white panelled hall, denied the necessity of washing his hands immediately, and followed Laddie ... into the garden." That is what I mean by hinting that when Mr. Sadler discovers what to leave out we shall all be the better for it.

In these days of massive trilogies, when your novelist demands at least four hundred pages in which to bring his hero's career up to the point where he is informed by his private-school master that he has passed the entrance examination for Harrow, it is a refreshing change to come across a book like The Captive (Chapman and Hall), opening in the middle of the story with an almost cinema-like abruptness. Miss Phyllis Bottome is no believer in the leisurely type of novel. The story snatches you up and whirls you along, and you have no more chance of getting out of it than if you were in Niagara Rapids. Miss Bottome has hit on an ultra-modern problem as the basis of her latest story: what is to be done with the woman who is sufficiently advanced to be bored with the sheltered life yet too conventional to fit comfortably into the life that is broader and more vivid? This is the fate of Rosamund Beaumont, who flies from the conventional, as represented by Philip Strangeways, to the unconventional, in the person of Pat O'Malley, the impecunious artist of Rome. There was that in her which prevented her settling down "in endless English comfort, by county folks caressed"; but, on the other hand, she did wish Pat would dress for dinner, and, while she made no real objection to his friends, she "only wanted to know who people were, and if they must have them running in and out at all hours, as if they kept a station waiting room." In the end Pat very naturally seeks consolation with a fellow-artist and friend of ten years' standing, while Rosamund, after the divorce proceedings, returns to England and marries Philip, and is now being thoroughly bored by that excellent but limited young man. Miss Bottome has all the talents. She draws characters that step out of the pages and walk before one; she establishes atmosphere with an economy of words almost miraculous in these long-winded days; and she contrives, without straining for epigram, to insert in every chapter phrase after phrase worthy of the reviewer's best compliment—the pencil-mark in the margin.

When I found myself confronted with a volume of very short stories over the signature of "George A. Birmingham" I was at first inclined to suspect that the limitations of such a medium would not allow scope for the exercise of that delightful author's special and peculiar gift. You know what I mean. That involving of the reader in a maze of absurd but severely logical intrigue that keeps him breathlessly pursuing laughter through chapter after chapter. In a sense I was both right and wrong, chiefly the latter. Though there are some stories in Minnie's Bishop (Hodder and Stoughton) that practically anybody else could have written, there are also others that show Mr. "Birmingham at his best. Especially would I wish to record my delight in three quite exquisite little sketches of character—"Onnie Dever," the story of a barefoot fisher-girl who became the leading lady in an American dress emporium; "Bedclothes," which tells how a curate, smothered in conventionalities, obtained relief; and one other, a thing of the tenderest and most delicate art, which I will leave you to identify for yourself. A word of warning: do not be put off by the fact that for some obscure reason the author has chosen to name his volume after a story that, though it comes first, is a long way the feeblest in the collection. There are others that for wit and wisdom in a little room will make ample amends.

In these days a treaty, being only written on paper, is easily dealt with.

But it was a more troublesome matter in the times of bronze tablets.