Punch/Volume 148/Issue 3851

CHARIVARIA.

The cost of the War up to date is estimated at £5,867,000,000. This seems a great deal, and we cannot help thinking that there must have been extravagance somewhere.

⁂

"For every maltreated German submarine seaman," says Die Post, "Germany must seize an imprisoned British officer and subject him to a tenfold more cruel torture. No middle course is possible. We have the example of the Middle Ages before us, let us follow it." This frank confession on the part of Germany that she is a bit behind the Middle Ages is illuminating.

⁂

According to the Kreuzzeitung, St. Paul's Cathedral is filled with machine guns and other military material. It is always interesting to account for an exaggeration, and the origin of this one is no doubt the fact that a few minor canons have been seen in the sacred edifice.

⁂

"KILL THAT FLY!

Necessity for a rigorous campaign."Globe.

At last the British public is waking up to the Zeppelin danger.

⁂

It is denied, by the way, that the three bombs which were found in the grounds of Henham Hall were deliberately aimed at that mansion on account of its having been converted into a hospital; they just fell there instinctively.

⁂

"Yesterday the English made use of grenades and bombs in the vicinity east of Ypres which omit suffocating and noxious gases." This message, The Globe tells us, was sent out by German wireless, and it is satisfactory to note that the enemy admit our methods to be more humane than their own.

⁂

An inhabitant of Cologne has been fined £3 for giving war bread to his dog. The proceedings were instituted, we understand, at the instance of the local Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

⁂

"Has a place-name any right to a mark of exclamation?" asks Observator, in The Observer, and instances the case of Westward Ho! It is certainly curious that the much more violent expression "Amsterdam" should have none, and that some of the most difficult names in the War area have no such comment permanently attached to them.

⁂

The Strand Theatre's new play is, we see, written by Harriet Ford and Harvey J. O. Higgins, "in co-operation with Detective William J. Burns." Was the Detective, we wonder, called in to unravel the plot?

⁂

Quite a little panic, we hear, was caused among elderly Music Hall artistes the other day by the announcement that a lecture was to be delivered at the Royal Institution on "Stars and their Age."

⁂

Grave-diggers in several parts of the country are agitating for a rise in wages on account of the increased cost of living. The difficulty, of course, is that, if a rise be granted, it may lead to an increase in the cost of dying.

⁂

The Government remedy for the drink evil is to be, we are told, "Low alcohol." And we believe that even that will be lowered.

Mother. "Well, Master Jim hasn't gone to the front after all."

Cook. "Oh, poor Master Jim! And 'e's so fond of a day's shootin'."

"The Governors have a Temporary Vacancy for a Teacher (either Male or Female) of Temporary Mathematics, Physics and Chemistry."—Spectator.

Let us hope that they also have a Permanent Vacancy for a Teacher of Permanent German.

"PARIS, Wednesday.—The following official communiqué was issued to-night:—

A Zeppelin threw bombs near Bailleul at our communiqué of last evening."

Western Evening Herald.

Another German attempt to suppress the truth!

ROME'S DELAYS.

[To my host of a certain Italian restaurant in London, who ever since last August has assured his clientèle, on the strength of confidential information, that his country is on the very point of coming to the support of the Triple Entente.]

Ere yet the swallows southward drew,

When everybody stood at gaze

To see what Italy would do,

With fine assurance you would speak,

Saying that she would soon be in it—

To-morrow, or the ensuing week,

In fact at almost any minute.

From sources secret as the tomb,

You would impart the fateful word

That spelt the loathed Tedeschi's doom;

Spiced like the good Falernian brand

That marks you out among padroni,

It cheered my heart, it nerved my hand

To wrestle with your macaroni.

And, sitting where he'd always sat,

Emmanuel on the fence remained,

But you were not put off by that;

"'Italy Unredeemed,'" you 'd say,

"Enflames our bosoms like a foment;

Something will happen some fine day—

Indeed it might at any moment."

And Spring, that calls the swallows home,

Sees your desire still fixed on Trent

But nothing doing down in Rome;

And still you nurse your sanguine views

And with the old conviction state 'em:—

"On Monday next!—I have the news—

We mean to send our ultimatum."

And Italy postpones the start,

I would not chill your fiery soul

Nor dash your confidence of heart;

But if she can't make up her mind

To join and soon—the general outing,

She may arrive too late and find

The funeral over (bar the shouting).

O. S.

UNWRITTEN LETTERS TO THE KAISER.

No. XX.

(From the Crown Prince of Bavaria.)

All Highest War Lord,—I hasten to inform you that, in accordance with your most respected and ever to be promptly followed suggestion, I have to my brave Bavarian soldiers another proclamation issued, bidding them to deal roughly and swiftly with the by you despised British army to which they are opposed. For the writing of this proclamation I have used some all-glorious models which, lest I should forget the style of them, I always by me keep. I have assured my soldiers that they are fighting to defend their Fatherland against the since years plotted attacks of these prominently-toothed and long-legged mercenaries, who are driven to battle by mere fear of floggings to be inflicted on them by their splenetic officers, who themselves are afraid that if we Bavarians conquer them they will not be supplied with roast beef and plum pudding four times in every day, but will have to be satisfied with the true German calf's cutlet and black bread, of which, together with potatoes and liver sausage, they are brutally attempting to deprive us.

I have also put in what I hope will be considered a tactful allusion to God as the trusted ally of the Germans, and have asked my soldiers to remember that they are carrying on the War for freedom, so that, for instance, the poor Belgians may be able to understand that friendship with England means misery, while friendship with the civilised armies of the German Empire means perpetual happiness and much wealth. Finally, I have asked my soldiers to drive the accursed invaders—for it is their intention to invade us—into the sea, and to do it as roughly as possible in the old splendid Bavarian way—though, to be sure, we Bavarians, being an inland people, have but little acquaintance with the sea and do not desire to increase that acquaintance.

Be that as it may, I have done my best, and have had this fire-breathing proclamation read at the head of every Bavarian regiment in the fighting line. One cannot pause to be strictly truthful in a proclamation. Your Majesty knows this as well as anyone, you being yourself a master in that kind of romantic writing, and you will make allowances, I am sure. Some stimulus the soldiers require, for they know for certain that for months past they have stuck tight in the same place and have even from time to time been beaten back from their trenches in a highly unexpected and most inconsiderate manner. If this sort of thing is to continue, even my honest Bavarians may begin to murmur, for they will think with profound yearning of their village-homes and of the delicious beer they used to drink with so much happiness in the days which now seem to be a dream that cannot return.

When I myself think of Bavaria, with its many thousands of breweries, all made prosperous by the patriotic thirst of a cultured people, I confess that my heart grows heavy in my breast, and, in spite of all my proclamations, I find myself regretting the joys of peace and longing for the swift end of this infernal war in order that we Bavarians may get home to our beer and that the English may use their long legs, not for rushing at us on the battlefield, as they now do, with a most murderous result, but for striding back to their transports and so being comfortably conveyed to their own barbarous and foggy island. That ought to be a sufficient punishment for them. Let us, then, as quickly as possible make an end of this War before worse things happen to us. For glory we have assuredly done enough. Let us now take into consideration the safety of our Fatherland, whether it be Bavaria or Prussia. We cannot go on fighting for ever and never gaining any ground, and I am sure that it is better to drink Bavarian beer in peace than to live in trenches and be bombarded by the English, however bravely we endure it. I hope, therefore, that you will not ask me to write any more furious proclamations.

Your sincere Friend and Admirer, Rupprecht.

"Evensong was held at eight o'clock. Collections were made for the rich and poor."—West London Observer.

The collection for the rich was a particularly happy thought. There is probably no class that has been more severaly hit by the War.

"Ronnie, the captivating son of the Earl and the girl, and, incidentally, the 'days ex on achina' is quite admirably done."

Yorkshire Post.

On this occasion the god seems to have stepped out of the machine (linotype), and been replaced by the devil.

"IN THE SPRING A YOUNG MANY'S FANCY———"

The Crown Prince. "I DON'T BELIEVE I WAS MEANT TO WIN BATTLES; I BELIEVE I WAS MEANT TO BE LOVED."

PEOPLE WE SHOULD LIKE TO SEE INTERNED.

Visitor (brightly). "Now, chatter away, and tell me all about it."

MY ORDERLY.

"Would ye believe it, Docthor," said my medical orderly, Daniel O'Farrell, the other day, "but a hungry German walked into this very village this mornin' to surrinder himself widout his hilmut? 'Go back and fetch it, ye owdacious Teuton,' says I. 'There's Mary Delaney sittin' at home somewheres in Cork wid the fixed determination niver to marry me until I sind along to her a German hilmut for to hang up in the parlour window wid a pot of ferns in it. Go back, ye Hun, and if ye've any decent feelin' don't come here again widout it.'"

To the "Halt! Who comes there?" of the sentry outside my billet the other night, I heard Dan saying, "Frind it is, but only in the rigimental sense of the word, Peter Murphy, until ye widraw the expression ye used about me yisterday." This in reference to an occasion at the village estaminet when Murphy had introduced him to a gunner friend of his as "the regimental goat."

But it is in the trenches that one sees O'Farrell at his best. As he crawls behind me with the medical panier on his back he keeps up a lively whispering, especially when we happen to be working our way behind those of his more intimate friends whose domestic foibles afford him an opening.

"It's no use, Patrick, annyone can see ye're used to nursin' twins by the way ye handle your rifle."

"Is it composin' a Hymn of Hate to your landlord, ye are, Mike? Shure it's a blessin' ye've no rint to pay for the trinch, or it's sorra a week ye'd be out here."

Or to Riley, a notoriously henpecked man in domestic life: "Enjoyin' the quiet, Riley? Well, well, no man deserves a restful day's shellin' more than ye do."

Suddenly a "Jack Johnson" explodes with a terrific din on a sand-hill in front of our line. The somewhat strained silence that follows is broken by a cheerful and familiar voice:—

"A more wasteful and extravagant way of shootin' small game I niver did see before, Sorr. Though one mustn't be hard on the craythurs, seein' that they might aisily have mishtaken the runnin' of the rabbit for an ambulance movin' in the distance."

Just at present he is in his billet teaching a local farmer's daughter to sing "Kathleen Mavourneen." The result is not melodious, but they are both exceedingly happy, and as I came by the window I heard his encouragement:—

"Whin ye can say 'Oireland' widout makin' a face over it, believe me, ye'll be well on the way to shpakin' English."

The War would be a much sadder thing to me without O'Farrell.

"What further part Paignton is destined to play in the Great War will be made clear as time goes on. There never was, and we confidently believe never will be, a shadow of doubt of the splendid loyalty of the town, and whatever the sacrifices many have to make—and they are many and diversified—all will be borne with but one object and one determination, which is to see the war through to the bitter end 'with no complaining in our sheets.'"—Paignton Observer.

If the Kaiser expects to see Paignton in a white sheet he will be disappointed.

"Wanted, a Two-Legged Horse, not less than 16 hands.—Apply, Borough Surveyor, Tamworth."—Tamworth Herald.

Unless the animal is wanted for the local museum we should suggest that one with more legs, even if fewer hands, would be preferable.

"Look, Alfred, there's the new moon. Have you bowed?"

"No, and I'm not going to. Last time I did and she cut me."

ON THE SPY TRAIL.

IV.

The man next door has had a shock to his system—it was the same man who told Jimmy that snowdrops were harbingers. You see, Jimmy's bloodhound Faithful was sitting on the window-ledge of Jimmy's bedroom catching flies for coming through the window at him. If they didn't come through, he just said "Snap" and caught them as they went by. Faithful is a good snapper, and caught ten flies and a bee. He didn't want the bee really. You see the bee thought Jimmy's bloodhound was a geranium, and settled on his nose. Faithful turned both eyes inwards to get the bee in proper focus, and then they both said "Snap" at the same time, and fell out of the window together.

The man who was passing below had his umbrella up and was expecting rain, not bloodhounds and bees, Jimmy says.

Instead of getting up off the ground, he lay quite still, and put his fingers in his ears waiting for the bang. He knew you had to lie flat on the ground till the bomb went off, but he didn't know how long you had to stop there while it did it. Jimmy says the man appeared very thoughtful when he got up; he seemed to be considering something.

It took Jimmy a long time to find his bloodhound, and then he found him holding his nose in a bucket of water to cool it, and looking from side to side as if he expected another bee. Jimmy says it was all right when he tied a blue bag on to Faithful's nose, except that Faithful had to keep looking round the corner of the blue bag to see where he was going.

Jimmy says Faithful must have swallowed the bee, because when his nose got all right he swallowed the blue bag. Jimmy says bloodhounds have got a lot of instinct like that, and it's done by careful breeding. Faithful was very restless that night. Jimmy thinks the blue bag or the bee must have curdled on his stomach. He tried to sing himself to sleep, but he couldn't go off.

Jimmy says Faithful then tried to go to sleep by counting sheep, but he couldn't, for every now and then he would jump up and chase one of the sheep, and then he had to start all over again.

Jimmy says the man next door said "Hush!" just like that.

Jimmy's bloodhound wasn't quite himself next morning for some reason or other: he had a hiccough for one thing, and seemed perturbed. Jimmy says the bee must have felt a bit unstrung too, as he couldn't hear it buzzing when he listened outside Faithful. Jimmy says that perhaps it couldn't see well enough to buzz.

But whenever Jimmy's bloodhound loses its iron nerve, it has a way which soon makes it feel bold and daring.

It's a tortoise, and it's a hundred-and-three years old, Jimmy says.

Whenever Faithful sees the tortoise he always pulls himself together and dares the tortoise to come out of its shell. Jimmy says that when the tortoise refuses to growl back Faithful gets husky with rage and puts his mouth close to the tortoise and bays down the telephone at him.

Jimmy says Faithful will sometimes wait hours for the tortoise to come and really have it out with him, and just when Faithful is getting tired of waiting the tortoise will slowly push out one hind leg and wag it at him, and then draw it back quickly just as Faithful is going to begin.

Jimmy says Faithful doesn't know the tortoise is a hundred-and-three years old, that's why. But Jimmy could see Faithful had got his iron nerve back again, because after he had had a little snooze he climbed under the hedge and went and drank the milk that had been put out for the cat next door.

Jimmy says the cat came at half time and deliberately went up to Faithful and gave him the coward's blow, and when Faithful was going to hurl the taunt in her face she went and looked like a camel at him.

Jimmy says it was awful, for you know what bloodhounds are when they are roused. They just catch the cat by the middle of the back, throw it once—only once, Jimmy says—up in the air, and then leave it for the gardener to bury.

Jimmy says it's all done by knack, and that's why cats push their backs up out of reach; they know.

Jimmy says it was a very unwilling cat, and was very rude to his bloodhound; it did something at him with its mouth, so Faithful just came away and bided his time; he is a good bider.

In the afternoon Jimmy took Faithful on the trail: he wanted to catch a spy before the grass got damp. He tried a different direction this time, but Faithful seemed to know. He soon got into his steady swing, and led Jimmy right away to a house which stands a quarter of a mile back from the road. They had to crawl stealthily along a hedge, and then through another hedge on to a lawn.

Jimmy says he hid behind a laurel bush whilst Faithful did his deadly work. Jimmy says it's a grand sight to see a bloodhound working well. Faithful first visited some bones he knew of in a tulip bed; Jimmy says they may have been human bones—of another spy. Then Faithful advanced very cautiously to an open window, on the ledge of which a lady had just placed some crumbs for the birds. Jimmy says Faithful very carefully placed his paws on the window-ledge and, gradually drawing himself up, reached out with his tongue.

Jimmy says the lady must have been in the room and seen Faithful's full face rising at her over the window-ledge, for he heard her give a gasp like pouring cold water down another boy's neck.

When Faithful heard the gasp he stopped reaching out for the crumbs and, holding on with all his might, he fixed the lady with his eye. Jimmy says the lady sank amongst the furniture, he could hear her doing it; but before she did it she said something to Faithful which caused him to lose his grip and fall with his whole weight right back on a pink hyacinth: it bent it nearly double, Jimmy says.

It is awful when a bloodhound fixes you with his eye, Jimmy says; it goes all down your spine and makes you feel like you do when the photographer takes the cap off the camera at you.

Jimmy says that Faithful looked quite downcast when he saw him in the road; it was because he knew he had made a mistake. You see Jimmy had seen the lady before; her name was Mrs. Jones, and she used to collect for the War. But could a prize bloodhound like Faithful possibly make a mistake? that's what puzzled Jimmy.

Jimmy saw the lady again two or three days after when she called to see his mother. Jimmy says Susan opened the door, and the lady told Susan she had called for the War. Susan said if she would step inside she would get it for her. Jimmy says Mrs. Jones. stepped inside and began to wipe her feet upon his bloodhound, who happened to be lying down curled up in the hall.

Jimmy says that's one of the things you should never do with bloodhounds; it goads them. Jimmy says Faithful must have been thinking of the bee in his sleep, for he said "Snap" very quickly this time, before the lady's boot could say it back, and then he did the side stroke upstairs as hard as he could.

Mrs. Jones was very angry with Faithful for saying "Snap" first. She said some words to Jimmy's bloodhound which Jimmy had heard before. Jimmy says it was on the day when he bought a lemon to suck in front of a man playing the flute in a German band. You have to let him see you sucking it by making a juicy noise with your mouth, Jimmy says, and it makes his mouth water, and all in good time he throws the flute at you. Jimmy says you do it by being very quick, and you can hear the German words coming after you as you go along.

Jimmy says Mrs. Jones only said some of the words, and then settled comfortably on the floor with her head in the umbrella-stand. Jimmy's mother heard one of the words; it was "verfluchter." Jimmy says his mother would make a splendid detective if she were only a man. When Mrs. Jones recovered and wanted to go and have her leg amputated, Jimmy's mother took her into the drawing-room and began writing down names in the lady's Belgian Relief book. She told Jimmy she put her own name down for £10, and then Jimmy's for £5, and then Susan's and Faithful's, and kept breaking the pencil after every entry. She said she thought the policeman would never come, and was just going to put his name down for a lot of relief when he brought it himself.

Jimmy says they went very quickly to the police-station because when the cabhorse turned round and saw Faithful he bolted.

The policeman told Jimmy next day that it was a clear case, and that the magistrates were going to sit on Mrs. Jones next week for being a spy.

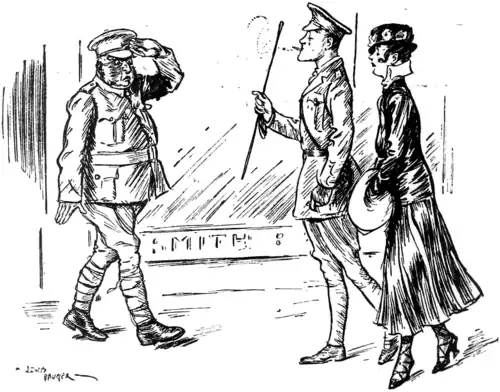

How Sir Benjamin Goldmore and his junior clerk used to pass one another if they met in the City—

—And how they pass one another now.

THE BRIDGE-BUILDERS.

Before we went into camp our Commandant had been learning to tie knots. In order to let his knowledge off on us he decided to build a bridge and asked us to help him. Bridge building requires a number of pieces of wood. These can be commandeered without difficulty if the owner isn't about. If he catches you, you appeal to his patriotism. The bits of wood are tied together with rope and lashings (string and twine stretch too much). If the bits of wood stay where you have tied them, you call the result a bridge; if they change their positions much you rename it a boom or barricade according to whether you are using water or not. Water isn't essential to bridge-building, but it adds to the amusement. If the bridge stands up long enough you call in the photographer. You further test it by detailing the officers and men whose loss won't affect the efficiency of the Battalion to tread on it. This affords practice for the stretcher-bearers and hospital orderlies. When you have discovered how many men the bridge won't carry, you can either reconstruct it or revert to the boom or barricade theory.

Our Commandant, who has a sense of humour, borrowed a pond. We succeeded in commandeering the wood, though not without having to appeal to the owner's patriotism. We told him that every log which he lent us would probably save the life of a man at the Front. He was either very obtuse or no patriot, and we had to promise to return the logs in the same state of repair in which we found them (fair wear and tear excepted). As our Commandant wasn't present we offered his personal guarantee. The log-owner knew our Commandant, and we had to throw in a Quartermaster and Paymaster. The Quartermaster got the rope and lashings on credit.

The pond had a ready-made island in the middle and we were ordered to throw the bridge on to the island. Bailey didn't understand that the word "throw" was used in the technical sense and started with the ingredients. He was short with the three first logs and the splashes attracted the attention of our Company Commander. This of itself was enough to spoil Bailey's day, apart from other incidents.

We laid a number of logs on the ground in a nice pattern and the Commandant named the pieces. We never decided on the name of one big log; I called it "Splintery Bill" (after the Adjutant), the Commandant called it a "transom," and the Adjutant, when it fell on his toe, called it something else. The Commandant showed us how to use his knots in tying the logs together. We made the knots, and he said that we had constructed a trestle. When we tried to stand the thing on end it didn't look in the least like a trestle. Our Commandant said we hadn't made the knots as he told us, and that he would have to do it himself. When he had finished, it held together better, but didn't look quite sober. After a third combined attempt we were able to attach road-bearers and get it into the water. We started to hammer it into the mud, but some of the blows weren't accurate, and Holroyd had to retire to the hospital tent while we repaired damage. Eventually we got the trestle fixed up and attached pieces of wood called chesses to the road-bearers. If these things are properly applied you can walk on them, and our Junior Platoon Commander was requisitioned to demonstrate the fact. Either he didn't tread on the good chesses or the whole thing wasn't as practicable a piece of work as it looked. He joined Holroyd in the hospital tent.

The other trestles had to be erected in deeper water, and wading volunteers were called for. Our uniform isn't guaranteed unshrinkable and there was a shortage of volunteers. The discovery of a boat seemed likely to solve the difficulty. The boat wasn't found in the water, so we didn't know for certain if it was watertight. No mention of this possible defect was made to Bailey when we started him on his cruise. Bailey was half-way between the bank and the island when the boat sank. Bailey can't swim very well and a fatigue party had to be told off to rescue him. Bailey and his rescuers all say that the corps ought to pay for their new uniforms. Since then our boy buglers (to whom the shrunken uniforms were transferred) have declined to wear them on the ground that they haven't shrunk in the right proportions. Boys are far too fastidious now-a-days; it is absurd to suggest that they cannot bugle evenly with one sleeve shorter than the other.

We got the bridge finished without many more accidents and appointed the committee to test it. Our Commandant wouldn't lead the committee. He said that they were retreating and that he was going to direct operations against the advancing enemy from his proper place in the rear. Only four men retreated over the bridge. When it collapsed two Platoon Commanders remained on on the bridge to the last. The men who had got on to the island seemed pleased with themselves and rather amused when the bridge became a boom. They were quite upset when they found out that we hadn't time to build another bridge for them to cross back again. It was the hour for tea, and bridgebuilding is really engineers' work. It isn't necessary for riflemen to keep on at it when they have once learned how it is done. The islanders said that they would rather stay where they were than go home through the water. The Commandant said he didn't mind so long as they were comfortable, and we marched back to camp.

They arrived in camp very wet and hungry just before "lights out." They had got to dislike the island. They said the place was damp and unhealthy, and that the only available food was a duck and some duck's eggs. They hadn't any means of cooking the duck, and the bird, who was sitting on the eggs, refused to be dissociated from them. In any case there was nothing to indicate their age. The society, too, was limited; they weren't on very good terms with one another; and the duck, owing to its interest in the eggs, was quite unclubable.

On the following day there was a very interesting triangular discussion between the log-owner, the pond-owner and our Commandant on the rights of property.

HUNNISH.

The New Language.

The Hamburg Fremdenblatt proposes that a new verb, "weddigen," should be employed in the sense of "to torpedo," as a lasting honour to the man who blew up so many British ships. We suggest the following additions to the new vocabulary:—

- bernstorffen = to spread the light in benighted neutral countries.

- wolffen = to follow in the steps of George Washington.

- bülowen = to give away other people's property.

- tirpitzen = to grow barnacles.

- svenhedin = a revised pronunciation of schweinhund.

- strafenglander = humourist or funny man.

We even hope to see the list extended to include the phrase "to berlin."

"In the affair of Wednesday night the invader found himself at a loss. His objective was clearly Newcastle. Yet he got no nearer than Walsall."—Globe.

This praiseworthy attempt on the part of The Globe to mislead the enemy as to his whereabouts was unfortunately frustrated by other journals, which gave the place correctly as "Wallsend."

Lady Customer. "Yes, this is better weather now. Some people think all the rain we had a little time ago was caused by the firing of heavy guns in Belgium."

Dressfitter. "I don't see how that can be, Madam, for I remember we mostly had very fine weather during the South African War."

SOME NEW WAR BOOKS.

With a Mouth Organ in Flanders.

By Magnus MacLuskin.

"This is incomparably the finest book on War that has yet been published. Mr. MacLuskin is a master of his instrument and plays upon the public like an old fiddle."—Daily Muse.

What I Think of Kitchener, Joffre and the Grand Duke.

By Ferdinand Tosher.

"This is a far better book than the best of us deserve. With insight and tenderness and courage Mr. Tosher has written a work which will live for ever and even longer."—Mr. Twisterton in The Daily Par."

Musings on Martial Matters.

By A Sandwichman.

"An arresting volume. This sandwichman will go far. Dostoievsky might have been proud to have written the chapter on the Sam Browne belt."—The Prattler.

"A soul-shaking book."—The Daily Grouser.

Lyrics of Carnage.

By Sheila P. Stote.

"The finest book that Mrs. Stote has yet written. Replete with luscious imagery and relentless realism. I have already given away ten copies to my friends. Mrs. Stote is the American Pushkin."—Clement Longmire in "The Orb."

1s. net in limp lamb-skin.

2s. 6d. net in crimson crash.

5s. net in purple velvet, with Portrait.

SMALL ADVERTISEMENTS.

If W. Hohenzollern, said to be a Professor of the Mailed Fist, will apply to Enver and Co., Queer Street, Constantinople, he will hear of something.

{rule}}

Wilhelm or Wilhelmina.—Will all with these names send their contributions as soon as possible so that more unarmed British may be sunk by our submarines? The need is great as the Enemy Merchant Service at present shows hardly any sign of being affected by our frightfulness.

Advertiser who, at beginning of War, purchased number of Ticklers with which to celebrate victories in streets of Vienna, would be prepared to sacrifice for low cash figure. A number of flags, also other bunting, for sale at clearance prices.

Gentleman, whose views on politics, etc., are well-known on 9.15 Surbiton-Waterloo, seeks greater scope. Would be prepared to take over general managership of Government business (as per speech of Chancellor) if conditions satisfactory.

People of Trieste!

Somebody else's

King and Country

Cede You.

Zeppelins for British-fed Poultry. Our Staff undertakes these painless extinctions.—Kaiser and Co., Family Butchers.

Woodrow Wilson's Soothers act like a charm. German friends should try one on the tongue at Hate time.

Commercial Modesty.

Inscription on a shop-window in Birmingham:—

"Ici on parle français un peu."

THE SLACKER.

THE "ORION'S" FIGUREHEAD AT WHITEHALL.

Whitehall aglimmer like a beach the tide has scarce left dry;

And there I saw the figurehead which once did grace the bow

Of the old bold Orion,

The fighting old Orion,

In the days that are not now.

And ships from out whose oaken sides Trafalgar's thunder rolled;

There was Ajax, Neptune, Temeraire, Revenge, Leviathan,

With the old bold Orion,

The fighting old Orion,

When Victory led the van.

And still the hearts that manned them live to sail the seas once more,

To sail and fight, and watch and ward, and strike as stout a blow

As the old bold Orion,

The fighting old Orion.

In the wars of long ago.

They wait—not yet, not yet has dawned the day for which they burn!

They're watching, waiting for the word that sets their thunders free,

Like the old bold Orion,

The fighting old Orion,

When Nelson sailed the sea.

And, be it late or be it soon, such deeds are yet to do

As never your starry namesake saw who walked the midnight sky—

Old bold Orion,

Fighting old Orion,

Of the great old years gone by.

Or be the game a watching game we'll watch and never rest;

But the fighting game it pays for all when the guns begin to play

(Old, bold Orion,

Fighting old Orion)

Like the guns of yesterday.

Another Impending Apology.

"Mr. Wing opened a more thorny subject by his inquiry whether the sale of alcohol will be prohibited in the Houses of Parliament, so as to 'bring its pulse into accord with the other palaces of the King'... Mr. Wing, who was evidently full of his subject..."

Scotsman.

An Infant in Arms.

"COOK.—At Winnipeg, Canada, on 15th April, to Mr. and Mrs. E. A. D. Cook, a daughter. Serving with the Cameron Highlanders. (Née Annie Johnston.) (By cable.)

Scotsman.

As her parents were so doubtful about her patronymic this youthful Amazon determined to enlist at once, and make a name for herself. }}

Onomatopoeia.

"A well-known boatman, Joe Studd, says: I was awakened by the buzz zof the enginzes."

Evening Star.

This typographical effort to imitate the sound of a Zeppelin does our contemporary credit.

The Kaiser in Art.

Portraits of our pious foe

By his fierce moustachio.

When you're drawing Wilhelm II.,

Any sort of face will do?

THE AWAKENING.

Prince von Bülow (to Italy.) "STOP, STOP, SIGNORA! YOU'RE SUPPOSED TO BE MESMERISED—NOT MOBILISED!"

ESSENCE OF PARLIAMENT.

(Extracted from the Diary of Toby, M.P.)

House of Commons, Tuesday, 20th April.—One slightly compensatory result of devastating War is reduction of number of Questions addressed to Ministers. Been known to stop short of the round dozen. Instinctively felt that at period of national crisis this cheapest method of self-advertisement is bad form. To-day—unaccountably except on ground that long week-end provides mischief for idle hands to do—flood set in with the old rush.

"Here is an extra Monday thrown into week-end," says honourable Member in privacy of his study. "Let us draft a few questions addressed to Edward Grey, Lloyd George, Tennant or all three. They've nothing particular to do and are well paid for doing it. We'll get our name into the Parliamentary Report and our constituents will see we're on the spot."

Accordingly Paper distributed this morning crowded with 157 questions, forty of them standing in five names that are familiar in this connection. Within limit of Question hour (which by Westminster clock runs only for three-quarters) 112 were put and answered. Replies to the rest will be printed and circulated with votes in the morning. That a game not worth the candle consumed in drafting them. You may circulate replies just as you may take a horse to the pond. But you can't make the public read them, and no one will know how active and intelligent are the authors of these forty-five belated queries.

"LA SOURCE."

The Member for Houghton-le-Spring.

(Mr. Wing.)

No other business being on hand, way made for Member for Houghton-le-Spring—quite a total-abstainer touch about name of constituency—to move his Resolution prohibiting, during continuance of War, sale of alcoholic liquors in refreshment rooms and bars of House. His Majesty's personal example specially cited in support of proposal.

Quickly made apparent that House was sharply divided, with preponderance of opposition. Collins, Kt., presenting himself to favourable consideration of House as a "total abstainer by birth," plumped for Resolution, as did By-Your-Leif Jones and other teetotalers, whether by birth or adoption. On the contrary (his favourite attitude) Arthur Markham, habituated to call a spade a spade, in extreme cases a pickaxe, denounced the motion as "pure cant."

"A Total Abstainer by birth."

(Sir Stephen Collins.)

Bonar Law put that view of it in another form. Members would support the Resolution, and if sale of liquor within precincts of the House were prohibited they would, he said, go off to their homes or their clubs and take their accustomed drink.

"In a time of stress like that at present laid upon the country," he insisted, "we should have less rather than more of the make-believe that is part of the daily life of all politicians."

As for Mark Lockwood, Chairman of the Kitchen Committee, who has hauled down from his buttonhole the carnation that had then had acquired the status of a parliamentary institution, he was so agitated that he stumbled upon a bull whose originality, breed and excellence made the few Irish Members present green with envy.

"The profits of the Kitchen Department," Mark wailed, "are growing less and less every day. If this resolution is passed it will reduce what is left, which is nil, by 50 per cent."

In face of this appalling menace, Resolution was shunted by adjournment of the debate sine die.

Business done.—None. House adjourned at 5 o'clock.

Wednesday.—Lloyd George is indebted to Mr. Hewins for opportunity of making the most important statement with respect to affairs at the Front heard in the Commons this year. Member for Hereford submitted Resolution declaring urgent necessity of enlisting under unified administration resources of all firms capable of producing munitions of war. Pointing out that motion was tantamount to a vote of censure, since it implied that the Government were not doing their duty and that the House ought therefore to pass a resolution calling their attention to it, Chancellor said he could not consent to its adoption. At the same time he cordially approved its suggestion, and proceeded to show in detail that it had long been embodied in policy and action of the Government.

Lifting the veil behind which for strategic purposes the War Office works, in a few sentences he brought home to least imaginative mind stupendous character of our operations. The 'contemptible little army" at which eight months ago the Kaiser sneered has grown till there are now in the field six times as many men as formed the original Expeditionary Force, all fully equipped and supplied with adequate ammunition. Wherever German shot or shell has made a vacancy in the trenches or in the field, another British soldier has stepped in to fill it.

As to ammunition the War Office has been faced by unexpected increase in expenditure. Taking the figure 20 as representing output last September, Chancellor showed that it has increased by leaps and bounds till in March it reached 388. He confidently anticipates that this month the ratio will proportionately advance. During the few days' fighting round Neuve Chapelle almost as much ammunition was expended by our artillery as was fired during the whole of the two-and-three-quarter years of the Boer War. And not only were our own demands met, but we could also help to supply the need of our allies.

Curiously small audience for momentous statement. Effect produced instant and impressive. So marked is success of new departure in direction of taking Parliament and the country into confidence on the trend of affairs at the Front that hope is entertained that it will encourage Ministers to renewed excursions on the same lines. Immediate result of speech, which Bonar Law hailed with patriotic satisfaction, was that Hewins' amendment was negatived without a division.

Business done.—Chancellor of Exchequer made heartening statement on position with respect to munitions of war.

Thursday.—In Committee on War Office votes valuable speech contributed to debate by Walter Long. Effectively, because without acrimony, he criticised certain actions of War Office, heads of which, being, after all, only human, cannot fairly be expected under unparalleled stress to be free from lapses into oversight.

One case mentioned made deep impression on Committee. A Brigadier-General, leading his men into battle, was hit by a shell and badly wounded, his Brigade decimated by thunderbolts from the enemy's concealed batteries. The General, reaching home out of the jaws of death, apparently lamed for life, was rewarded by being put on half-pay, not on the scale of General, but of Colonel.

The Member for Sark, who has personal knowledge of the case, tells me Walter Long might have added that this gallant officer, eager to serve his country at the Front, voluntarily resigned one of the prizes of his profession, and now finds himself crippled, stranded, on half-pay. This pour encourager les autres.

Fortunately Prime Minister present. Listened with sympathetic attention to Walter Long's story, especially to the Brigadier-General incident. Certainly worth looking into.

Business done.—Prime Minister moved, Leader of Opposition seconded, House acclaimed, Resolution recording "exemplary manner in which Sir David Erskine has discharged the duties of Sergeant-at-Arms, and has devoted himself to the service of the House for a period of forty years." House adjourned till Tuesday.

Teacher. "What does ff stand for?"

Child (learning Military March). "Fump! Fump!"

"The flames were soon extinguished, and shortly after returned to the fire station."

Newcastle Evening Chronicle.

They should never have been allowed to leave it.

BALM ABOUNDING.

[In an interview with a German journalist the Sultan is reported to have said he was so glad to hear that the Kaiser was in good health, a fact it was impossible to gather from the enemy's Press.]

All up the Dardanelles;

The foe may soon be pounding

Our gates with shot and shells;

But things of this description

Can't worry us a bit

When we peruse the gladsome news:

"The Kaiser's keeping fit."

To reach the Suez banks

Awoke no grief whatever

In our disordered ranks;

In search of consolation

We only had to think

"What boots the fact that we were whacked?

The Kaiser's in the pink."

The Goeben counts as nil;

But Deutschland's cheering story

Can cure our every ill;

And when Constantinople

Is smashed to smithereens

We'll make no moan if it is known

The Kaiser's full of beans.

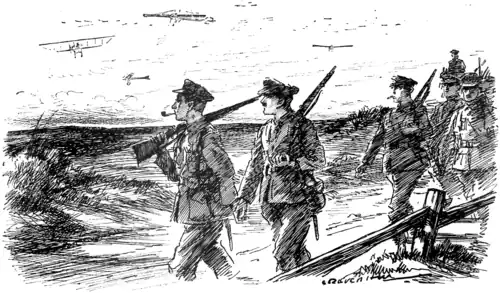

Tommy (on Salisbury Plain). "Mr, Bill! Ain't they tame round 'ere?"

THE EVER-ALERT.

I met my old friend the leader-writer on his way to work. His eye flashed his brow gloomed, his powerful jaws were set, his step was firm and determined. Shelley's lines floated into memory:—

I beheld, with clearer vision,

Through all outward form and fashion,

Justice, the Avenger, rise."

The third rhyme may not be quite up to modern standard; but the spirit is there, and it was the spirit that affected me. I felt that I too was in the presence of something very like Fate.

"What ho!" I said. On the warpath?"

"If you mean, am I going to the office? yes," he replied.

"Going to let some one have it hot?" I continued.

His demeanour increased in vehemence. "Of course," he replied.

"Who is it this time?" I asked. "Who is the last tired official who, after months of hard work and anxiety, has failed to reach your high-water mark and must therefore be lashed in public."

"I shan't know till I get there," he said. "There's certain to be some one. But how did you guess?"

"Not difficult," I replied. "Your very look showed me that. I can see that your duty is as plain to you to-day as it was yesterday and always has been. But for you and your punctual pen I don't know where England would be?"

His sternness relaxed. "I'm glad you think like that," he said.

"I do," I replied. "I think England was never to be so felicitated on her Press as to-day. Her leader-writers were never so vigilant for defects in our administration or so instant in proclaiming them for everyone to see."

He beamed.

"I hope so," he said. Then a shade of anxiety flittered over his brave stolid countenance. "You don't think there's any danger of our striking the rest of the world as a nation divided against itself, do you?" he asked.

"My dear fellow," I assured him, "what a ridiculous idea!"

He seemed to be relieved.

"The truth is above all," he said.

"It is," I replied, "far above. Out of reach for most of us, but never inaccessible to the grave and sagacious Press. You journalists know. All is simple to you. There are no complexities in administrative work. Black is black and white is white when one is governing a country, and there are no half-tones as in all other walks of life. Every mistake must be branded; no one's good faith must be trusted; no one in a difficult position must be helped. Don't you agree?"

"It is a mighty organ," he said. "I think that the importance of the Press as a critic of those in power cannot be over-estimated."

"With its eye and ear at every hole and all its agents busy, it must obviously know so much more about a department than the department itself," I said.

"Of course, he replied; "and in addition it frames standards and ideals of perfection by which it measures all those in authority; any falling short must be castigated."

"Immediately," I said.

"And without mercy," he added.

"In war time and under such a strain as the country is now experiencing you cannot be too drastic," I said.

"Exactly," he said. "There is more at stake; the Press has a sacred duty."

"Is all the Press equally sacred?" I asked. "Are the racing forecasts, for example, as sacred as the leaders?"

"Nothing is so sacred as the leaders," he replied. "Next to them the correspondence columns, where all kinds of scandals and abuses are ventilated and other attacks not necessarily less merited are made on those in whom the responsibility for England's success is vested."

"But what about the news?"

He fumed terribly. "There is hardly any news any more," he said. "The Censor in his benighted besotted folly..."

But I did not wait to hear the rest of the leader.

THE TERRORIST.

She was our cook, and a bad cook too; but a woman of genius. In the early days of her reign she must have gathered from the parlour-maid that Mother and I were prejudiced against tepid soup, burnt cutlets, and leathery omelettes. I went into the kitchen, intending to remonstrate, and found Cook gazing fixedly out of the window, sniffing at intervals, and apparently struggling with unshed tears. "Is anything the matter, Cook?" "No, Miss, nothing that you can help. It's only that it's a year to-day since I lost my sister Annie, and it all comes back to mind. The Coroner said it was the constant complaining and complaining that had weakened her brain, and led to———" "To what?" I asked breathessly. "Oh, to her hanging herself on a very strong hook in the cupboard's where her mistress kept her best dresses. I was sorry for the poor lady too, for they tell me the shock she got when she went to take down an evening gown, and found Annie instead, almost turned her brain. Yes, Miss, just complaints did it, and she near as good a cook as I am myself! But there, I mustn't be taking up your time with my trouble, must I?"

After that, could I dwell on the soup, the cutlets, or the omelette? Mother was decidedly upset too; and I have reason to believe that she spent that afternoon having the stoutest of the hooks in her own cupboard removed.

A short visit to some relations took me from the scene of action for a day or two. On my return I was met at the station by Cook, who had volunteered for the job. As we drove through a gloomy street she kept craning her neck out of the window, reading, half aloud, the numbers on the houses.

"Twenty-two, twenty-three—ah, there it is, twenty-four. That's the house where Lizzie died, Miss, my poor sister." "I thought her name was Annie." "Oh, that was the youngest but one, Miss; Lizzie came next to me, and we were as like as two peas. Poor soul! Well, I don't wonder the house is shut up; the neighbours, afterwards, used often to hear her crying; not to mention the charwoman, who was always meeting her on the stairs, and getting the sort of turn that makes you feel like brandy." "Good gracious, Cook! Do you mean that she died—suddenly?" "It must have taken a few minutes, Miss, owing to the bath not having been as full of water as she might have wished." "But how awful that two of your family should have———" "We're so sensitive, Miss, all of us; we got it from poor Mother. But at the inquest the Coroner said some very sharp things, holding that it was want of sleep that drove her to it: we can none of us get a wink of sleep before a midnight—it runs in the family—and Lizzie's mistress, not understanding, and making her get up before she had her sleep out in the morning, brought it all about."

My feelings may be imagined when Mother said to me that evening—"My dear, you must speak to Cook; she is upsetting the whole of the house: nothing will get her up before eight in the morning, and of course that makes breakfast late and all the maids cross." I had to mention the bath, and Mother turned pale. She had a tub in her own room for some days afterwards; she said she preferred it.

At last we became firm; Cook must go. I went into the kitchen to give her notice. That woman was a genius, or else bad second-sight; before I could utter a word she insisted on showing me the photograph of a singularly plain young woman. "My oldest sister, Miss." "Oh, that is Lizzie?" "No, Miss, that is poor Emily." "Is she dead too?" I asked desperately. "Yes, Miss; you see her mistress gave her notice, and it has always been a rule in our family to give it, not to take it, and it somehow broke her spirit. Whether she mistook the bottles or not, well, as they said at the inquest, the only tongue that could have told was still; but those that uses spirits of salt for cleaning out gas stoves must settle with their consciences here and hereafter."

I believe Cook would be with us still had not Providence sent an angel in the form of the wife of the Vicar of the parish from which our treasure came.

"And how do you like Sophia?" she asked amiably.

"She has many drawbacks," said Mother nervously. "Sometimes we think her a little eccentric; but possibly, poor thing, all those awful tragedies in her family really upset her brain." "I don't remember any tragedies," said the Vicaress thoughtfully; "I don't think the Vicar would have allowed them." "I meant the sad deaths of three of her sisters." "But Sophia of was an only child. We know her since she was a tiny tot; she was always most well behaved, though some people thought she was not quite so candid as she should have been, considering her big blue eyes." "Was she christened Sophia or Sapphira?" I asked meekly. "Sophia," said the lady firmly.

"My dear," said Mother, "give Sophia a month's wages and board wages in lieu of notice; tell her to pack; tell the housemaid that she is not to leave her alone for one second; order a cab to be at the door in half-an-hour."

The Terrorist left unwillingly. I am sure she still had a brace of sisters up her sleeve.

AN ESSEX TALE.

Maid to old Lady Deloraine,

At eight o'clock as usual came

To wake that formidable dame,

Jane's nerves were visibly unstrung

And checked the glibness of her tongue.

"Why, Jane," her mistress said, "you look

"As if you'd quarrelled with the cook."

"No, please your la'ship," stammered Jane,

"They dropped a bomb here in the lane,

Last night at one it was, I think;

Since then I never slep' a wink."

"What!" cried the other from her bed,

Her eyes protruding from her head,

"The German airships came last night,

And I not only missed the sight,

But never heard a sound before

Your knuckles rapped upon my door!

If you a grain of sense had got

You would have waked me on the spot.

I'd like to box your silly ears,"

And then she melted into tears;

While Jane, retreating, muttered,

"Lor! I never saw her cry before."

Business before Pleasure.

"Harold Fleming, the Swindon Town footballer and international forward, has been granted a commission in the 4th Wilts Regiment, and will take up his new duties at the close of the football season."

Daily Telegraph.

"After winning the final tie for the Blackburn Sunday School League Cup, the Great Harwood Congregational eleven marched to a recruiting meeting and enlisted in the Royal Field Artillery."—Daily Chronicle.

"The butler was a German spy... Mr. Volpé, whose unctuous manner as the butter-spy was worthy of a column of journalistic sensationalism."—Sunday Times.

"Unctuous" seems to be le mot juste.

"Organist (Voluntary) Wanted for Crumpsall Park Wesleyan Church: June.—J. 75, Evening News Office. Sat. Afternoons 3 to 5, 6d. Latest Music and Dances."

The Manchester Evening News.

The programme sounds attractive, but the remuneration is rather exiguous.

With enormous self-control we refrain from saying to what branch of the Service this very youthful officer belongs. "Officer shortly going abroad wishes to dispose of his Pram, which cost over £8 not 18 months ago."—Yorkshire Evening Post.

FURTHER ADVENTURES OF THE CULTURED PIG.

AT THE PLAY.

"Quinneys."

A preliminary interviewer, whom Mr. Vachell was too good-natured to resist, had wrung from him several interesting admissions; as that Quinney's was his best book; that the play, as plays should be, had been written before the novel; that the scene of Mr. Quinney's sanctum contained genuine antiques as well as admirable fakes; that his hero preferred things to persons, and that the author found in the excitement of producing dramas an excellent anodyne for the strain of wartime. I in turn was too good-natured to be put off by all this, and remained fixed in my resolve to see the play for myself.

And I was well rewarded with something very unusual. To begin with, Quinney was an honest dealer in antiquities, and this notwithstanding an apprenticeship in worm-hole-drilling. His morality, in fact, like his fortune, was self-made, and the natural pride that he took in these creations was not lessened by the fact that he came from Yorkshire. A righteous man among knaves, and a true lover of Art for its own beauty, he was not content with the virtues which he obviously possessed, but claimed others, including the quality of altruism. He could persuade himself (but not his wife) that the sweat of his brow had been poured out primarily for the benefit of his family. His helpmeet knew better, and did not hesitate to tell him that he preferred things (sticks and stuff) to persons. The subtlety of this appreciation, coming from a very homely intelligence, surprised me, yet it was not quite so clever as it seemed. The truth of the trouble was that Quinney did not make any distinction between things and persons. His wife and his daughter he regarded (quite kindly) as chattels that served his needs or ministered to his sense of beauty; in one he found the utility of a kitchen dresser, in the other the charm of a Dresden porcelain.

Mr. Vachell might well have been contented with his brilliant character-study, but he too is an honest man, and meant that we should have our money's worth. So he threw in a plot which turned upon the love-affair of Miss Quinney and her father's skilled workman, and was complicated by a deal in which Quinney's honesty was compromised by a fake that had escaped him. The plot served its purpose, though the interest of it was never very poignant. The real interest was intended to lie in the action going on in the character of Quinney under the pressure of circumstance and experience. We were to gather that he came to readjust his views of the relative value of things and persons. But I detected very little modification in his character up to quite the end, and I never have much faith in curtain repentances.

The Foreman. "This chair is faked."

The Master. "You're a liar."

The Foreman. "It's faked."

The Master (turning on magnifying-glass). "So it is, by goom!"

James Mr. Godfrey Tearle.

Joseph Quinney Mr. Henry Ainley.

Yet it was a drama all right, and Mr. Vachell had not forgotten his Classics. I cannot recall any hero of Greek tragedy who was actually a dealer in antiques, yet there was something a little Sophoclean about this picture of an honest man struggling with adverse conditions which were not wholly of his own making. On the other hand I will say nothing of the Sophoclean quality of the scene where Quinney looks on at the nocturnal love-tryst from behind a screen, and his daughter says, "Fancy if Daddy could see us now." This very elementary irony was obviously designed for beginners.

Mr. Henry Ainley had fitted himself tight into the skin of Quinney. This is the second fine character-study that he has given us since he retired from the profession of jeune premier. The same demand was not here made upon his imagination as in The Great Adventure; but, if his performance of Quinney was rather assimilative than creative the difference was one of character, and in both parts Mr. Ainley did his work just about as well as it could be done.

Miss Sydney Fairbrother, as the protesting phantom of a wife, had little to say, but her rare and unobtrusive interventions had a pleasant caustic quality. As Posy Quinney Miss Marie Hemingway was a very dainty figure and acted with great spirit. Mr. Godfrey Tearle, foreman and lover, showed his usual easy reserve of strength; and the succulent humour of Mr. A. G. Poulton as Quinney's brother-in-law, a gentleman who thought that one honest member was enough for any family of dealers, made me very tolerant of his detestable morals.

The first night's performance moved as smoothly as if the play had been running since the War begun, and I shall ask Mr. Lyall Swete, who produced it, to share the thanks and compliments which I now distribute broadcast upon all those who conspired to give me so delectable an evening. O. S.

"'He—"That's my friend Davis. He's in Kitchener's Army, you know." She—"What is he—a lieutenant?" He—"No, he's a lance-corporal." She (greatly impressed)—"O-oh, really! Influenza, I suppose."'—Punch.'"

Glasgow News.

We are much obliged to the kind effort of our Scottish contemporary to appreciate the joke in a recent issue of Punch, and regret that in this case the surgical operation should have been complicated by medical trouble.

"Millions of sandbags are wanted. This is an appeal to everyone to help. Women with sandbags, men with sixpence each, all will be forwarded to the firing line, and they are urgently wanted."

Sidcup and District Times.

The women with sandbags will no doubt be useful at the Front, but we do not quite understand the demand for men with sixpence each. They will be twice as valuable if they "take the shilling."

"AUSTRIAN EMPEROR RECEIVES KRUPP'S HEAD."

Edinburgh Evening News.

It is hardly fair of a newspaper to raise its readers' hopes like this. There was no charger. All that really happened was that Francis Joseph gave an audience to Herr Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach.

Officer. "Well, Paddy, how do you like soldiering?"

Irish Recruit. "Rightly, Sorr. All me life I worked for a farmer, an' ne niver wanst tould me to shtand at aise."

OUR BOOKING-OFFICE.

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

Since Loneliness (Hutchinson) is unhappily the last novel we shall read over the signature of Robert Hugh Benson I wish I could with truth call it at least one of his best. But to write this would be a poor tribute to a distinguished memory; the fact being that, though it has qualities of power and observation, it is very far below some others of its author's works. For one thing, in his theme (marriage between a Roman Catholic and a Protestant) he is more frankly polemical than ever. The factor of religion is naturally never absent from his stories; but they have won their position by their humanity rather than by any more controversial qualities; and in Loneliness the humanity is lacking. Marion Tenterden, the heroine, is a young woman who has risen from obscurity to fame and fortune by the possession of a marvellous voice. She had been a devout Romanist, but in the fierce light that beats upon a successful prima-donna her religion lost something of its hold, especially when she found herself in conflict with authority over the question of her intended marriage. Deliberately and one by one all the joys that make life worth living from a worldly standpoint are withdrawn from Marion. Her voice fails; her betrothed—a little inhumanly—retires from the engagement; and, worst of all, her familiar friend, Maggie Brent, far the best character in the book, is killed in a motor accident. Throughout I was reminded of a shrewd criticism made by Mr. A. C. Benson in a recent appreciation of his brother, where he speaks of those cultured, attractive and apparently broad-minded Anglicans who in Robert Hugh's pages are foredoomed to collapse before the snuffy village priest. You must read this story; but it will not make you forget the far better things that you already owe to the same pen.

There appears to be no diminution in the cult of the crook, either in fiction or drama. The latest exponent of the gentle art of police-baiting is Mr. Max Rittenberg, who has strung a volume of adventure-stories round the figure of John Hallard, and published them under the somewhat cryptic title of Gold and Thorns (Ward, Lock). I have often admired Mr. Rittenberg's method before this; he has an easy and faintly cynical humour that makes agreeable reading. But I can't say that the present volume shows him to advantage. The fact is that the exploits of Hallard scarcely give the author scope for his best. The trail of the popular magazine is over them all a little too palpably. Hallard and his wife and their confederate (who called themselves Sir Ralph and Lady Kenrick and servant) move largely in the cosmopolitan smart set of swindlers and financiers who haunt international watering-places—a milieu especially beloved of the less expensive monthly journals. Their adventures vary pleasingly from the swindling of a dusky potentate at Venice to the discovery of faked treasure-trove at Monte Carlo. Myself I liked best the very promising scheme by which floating Casino was to be established in a liner anchored outside the jurisdiction limit of Rapallo. In this, as in most, there is an agreeable sequence of bluffs and scores by one adventurer after another, ending with the victorious emergence of Hallard. Practically all the tales have this feature in common, that the persons swindled are no better than the swindlers, so there is no one for whom you need be sorry; paste cuts paste throughout, and the moral of the whole appears to be that when rogues fall out there will generally be a third and greater rogue to come by the booty. Which may all be quite good fun, if a little mechanical. There is one excellent illustration, which the publishers were so certain I should like that they have triplicated it (it appears on wrapper, cover and frontispiece), but without acknowledgment of the artist's name.

Patricia (Putnam) I should call a placid novel rather than a brilliant. Edith Henrietta Fowler (Mrs. Robert Hamilton) has considerable gifts of observation, though in her character drawing she is perhaps a little prone to overemphasis. Also she knows the life of which she treats; has seen, for example, what a singularly uncomfortable abode a country rectory can be, and is not afraid to say so. Patricia had to go and live in the rectory with a kind uncle and aunt on the death of her father. Before that she had been quite well off and by way of leading the fuller life. Her frocks, for instance, were of the latest. At the same time her taste in dress was not what I can applaud, as when journeying with her relatives to the rectory she wore such thin shoes and stockings that on the muddy walk from the cab to the front door she got cold feet. Of course Patricia makes a mild sensation in her rural surroundings, which is increased when the son of the local big-wig turns out to be one whose society she had tolerated in the fuller life. There are some well-observed sketches of character, one of them, the Rector's wife, touched with real beauty. For the rest it is all quite gentle, and just a little reminiscent of the Parish Magazine; though the interest certainly quickens with Patricia's publishing indiscretions, which I shall not reveal. Still lemonade, one might call it, with just a suspicion here and there of some strictly non-alcoholic champagne, the result being a beverage rather for the thirsty drainer of circulating-libraries than for those who require their fiction full-bodied.

I should suppose that the Dead Souls of Nickolai Gogol, written in 1837, offers a not much closer picture of the Russia of to-day than does Dickens' Oliver Twist, written at the same time, of our twentieth-century England. For though we may have made a quicker pace and have many more miles of rails and wire to the given area (and is this not Progress?) there has happened for Russia between that time and this the fateful freedom of the serfs or "souls." This classic novel of Gogol's describes the adventures of a plausible rogue, Tchitchikoff, who has a get-rich-quick scheme, quite in the manner of the best American business farces, for begging or purchasing at a ridiculously low rate, to sell at a profit, those serfs who, though actually dead, are still legally alive till the next census, the purchaser not being informed of their demise. Mr. Stephen Graham's introduction to this re-issue by Unwin of an English rendering promises the reader much, and Mr. Graham is a better judge than I. Perhaps the rather matter-of-fact translation was responsible for a little of my disappointment. But no one can fail to appreciate this sort of thing:—"So that's the procurator!" (says Tchitchikoff as the funeral procession passes). "He has lived and now he has died; and now they will print in the newspapers that he died regretted by his subordinates and by all mankind, a respected citizen, a wonderful father, a model husband; and soon they will, no doubt, add that he was accompanied to his grave by the tears of widows and orphans; but in sooth, when one comes to examine the matter thoroughly, all one will find in confirmation of these statements is that he had wonderfully thick eyebrows!"

Una Field, introduced to us at the opening of Mr. William Hewlett's book as The Child at the Window (Secker) of a country vicarage, bewails herself bitterly at the close of the volume on finding that she is still an onlooker at life, and no more gifted with understanding than she was at the beginning; and this after experiences far more varied and peculiar than are usually vouchsafed to vicars' daughters, even though dowered with exceptional beauty and rich impulsive godmothers. Really, I could have warned Una quite early that, if she wanted to hear the world's heartbeat, she wasn't going on the right tack. She seemed to think that it ought to beat loud enough to attract her attention when she was busy with other things—chiefly herself. Never was there a lady who received so much kindness and made so little use of it. I need not follow in detail her depressing career from the time when, after being most generously brought up and educated by her godmother, she ran away (omitting the formality of marriage) with Cecil Rowan, left him on finding him to be what others had expected, and accepted the charity of Sybil Grey, a school friend of whose doubtful character and tastes she had full cognisance. Later, however, she took a dislike to her friend's habits, and went away suddenly without a murmur of thanks. Nor did she feel any obligations towards the Rev. Philip Corthwaite, an old adorer, whom she married for the sake of a husband and a home; but made an attempt to captivate Sybil's brother, another cleric. He, sensibly enough, would have none of her, and hurried off into the bosom of the Roman Catholic Church. Una's godmother and husband eventually forgave her all these peccadilloes that I have cursorily indicated, and a lot more that I have no time to record, and Mrs. Majendie persuaded her to start again with Philip. I wish him luck. And I ought to add that Mr. Hewlett has a real gift of characterisation, though the colours he uses are sometimes too startling to seem quite natural. His descriptive powers, also considerable, are often spent, regrettably enough, on subjects and scenes either sordid or absolutely distasteful. I should like him to write a book with some much more wholesome and cheerful people in it.

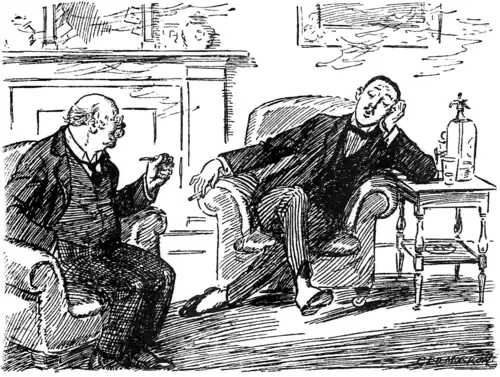

The Young Man. "As a matter of fact I think I've done rather well. You see, I've given four cousins and an uncle to the Army, three nephews to the Navy, and a sister and two aunts to the Red Cross organisation."