Photoplay/Volume 36/Issue 4/Racketeers of Hollywood

Racketeers of Hollywood

By Bogart Rogers

Pity the poor star who must defend his hard-earned bankroll from an army of versatile sharp-shooters

Illustrations by R. Van Buren

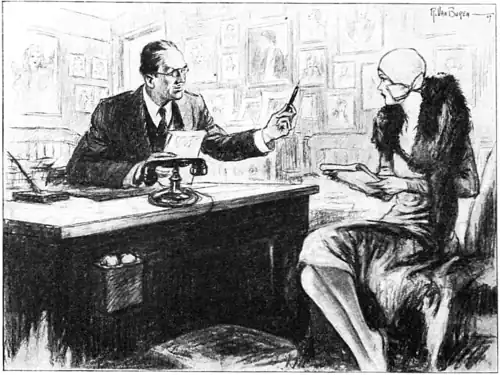

There is the "star-making" business manager. Youngsters will tumble and sign an agreement under which an agent is paid a certain percentage of anything they get on any contract. It's nothing but a "heads I win, tails you lose" proposition

A HOLLYWOOD husband discovers that his famous wife is too friendly with an equally famous director. He loves his little mate with that same deep affection a rattlesnake holds for a rabbit, but he burns with righteous indignation, rants about the sanctity of the home, threatens sensational divorce proceedings, and then―ah, then, to his delicately attuned ear comes the sweet tinkle of silver dollars.

His flinty heart mellows. He will be magnanimous. He will admit her accusations of mental cruelty and connubial incompatibility. He will be a gent, e'en though his heart is breaking. And he will deposit to his bank account a small fortune, contributed by his loving spouse and her noted admirer.

That, in case you fail to identify it, is a racket.

A Cahuenga Casanova borrows the girl friend's phonograph records―he will bring them back tomorrow night. Does he? Certainly not!

Tomorrow evening he presents them, with appropriate gestures, to yet another lady love.

That, also, is a racket.

Between these two extremes of grand and petty larceny you will find an amazing number and an infinite variety of bright ideas for getting something for nothing, of transferring coin of the realm from the pockets of those who have it to the billfolds of those who haven't and are too stupid, lazy or downright ornery to earn it by the sweat of their receding brows.

There are, in truth, more racketeers in Hollywood than ever congested the streets of Chicago. An honest Cicero beer baron would resent being classed with some of the staggering army of mouchers, spongers, panhandlers and cigarette borrowers who ply their profession north and south of the Boulevard. But on the other hand, the town has harbored a number of very astute operators whose records of remunerative achievement might well excite the admiration and envy of any dishonest man.

THE ultimate objective of this energetic army of sharp-shooters is, as you may well imagine, the comparatively small and practically defenceless group of stars, writers, directors and executives who are, as the Hollywood High School lads describe it, "dough heavy." Of course anybody with cash in the bank or readily negotiable securities is eligible, but the thousand a week and up people are the big, juicy peaches every Hollywood racketeer yearns to pluck and carry home for breakfast.

I'll venture to say that right this instant not less than a hundred men, women and perhaps children are pondering some scheme to carve a slice out of Mary Pickford's bankroll; that several hundred have designs on the life savings of Harold Lloyd; that untold thousands are trying to figure out some new and easy―it must not involve physical labor or it isn't easy―way of getting something for nothing from anybody who has it.

The most lucrative racket, for those who can get away with it, is blackmail. It stands as a constant menace to screen celebrities, be they guilty or innocent. It has been practiced successfully and attempted unsuccessfully countless times in the past and it will no doubt forever remain a source of annoyance.

With fame and fortune dependent so materially on the bubble reputation, the screen star twitches convulsively at the mere mention of a nasty public scandal. Guilty or not, the outcome always promises to be disastrous. The accusation makes more noise than the vindication, and in the meantime the Ladies' Club of Bird Center is likely to post bans. If the price is reasonable, it is more convenient to pay off than fight.

How do these extortionists work? Well, for instance―

The most lucrative racket, for those who can get away with it, is blackmail. It stands as a constant menace to celebrities, be they guilty or innocent. With fame and fortune dependent on the bubble reputation, the star cannot afford a scandal

THERE was a lawyer named Herman Roth. He represented Ben Deely, one of the husbands of the late Barbara La Marr. He knew his Hollywood, did Mr. Roth. He knew that when a screen star was at the height of popularity and in the big money, that was the time to snatch for the pocket book. Miss La Marr was riding the crest. Mr. Roth decided that perhaps something could be accomplished if Ben Deely sued for divorce and named a score or two of corespondents.

He knew, of course, that the very filing of such a suit might wreck her career. But he didn't file the papers―there isn't much money in just filing a divorce suit. He merely let Miss La Marr and the gentleman who had thousands of dollars invested in her pictures know what he was planning to do. Oh, yes. He was going to name a long list of corespondents, and a lot of well-known fellows they were, too. He would do it immediately―unless―well, he might reconsider and perhaps drop the matter entirely―but a lawyer had to be paid for his services just like anyone else.

Barbara La Marr decided she wouldn't stand for the shakedown. So she told Mr. Roth she would pay for his silence and arranged a meeting. She paid him in nice new bills. And when he had thanked her profusely, tucked the bills in his pocket, promised to forget the affair and bowed a polite adieu, a newspaper reporter and a large policeman closed in on him and appropriated the bills, which had been carefully marked.

For this little service to Miss La Marr, a jury awarded Mr. Roth a nice new denim suit covered with service stripes.

The moment anybody's salary in Hollywood tops the hundred a week figure some several hundred, or perhaps thousand, racketeers start concocting some scheme to cut in on it. The agents and business managers are always in the front rank. Now let it be understood that there are many reputable agents and some very capable and honest business managers. But there are just as many who are neither reputable, capable or on the level.

The favorite agent racket at the moment is this:

EVERYONE, of course, knows the financial possibilities of a "find," a new screen discovery with a chance to scale the heights. They start off as seven-fifty a day extras and ascend like rockets into the thousand dollar class. An interest in their potential earnings may turn out to be worth a fortune.

The self-confessed agents peel their eyes for promising material, for any boy or girl who looks as if he or she might possess the necessary attributes of stardom. In a realistic recital, they sell themselves. This picture business is a tough game, they declare. You've got to have somebody tooting your horn, somebody with entrée to the casting directors―somebody who knows where the bodies are buried. Give them a little time and they'll land a contract. It all sounds plausible. The youngsters tumble and sign an agreement under which the agents are to be paid a certain percentage of anything they get on a contract―any contract. They are sucker agreements, but a lot of the kids have signed them.

The agents go to work. Their efforts consist entirely of telling the youngsters they are pulling strings and promoting their interests generally. They always advise them to keep working as extras, which is an essential part of the plan. Sooner or later some director notices them and perhaps gives them a chance. Maybe a studio signs them to a short contract, with options if they make good.

In steps Mr. Agent and claims the glory. He was the man who brought this great fortune to pass. Nine times out of ten he didn't have a thing to do with it―but he collects under his little agreement just the same. The agent can't lose. If one of the youngsters gets a contract, he collects. If none of them do, it hasn't cost him a dime.

THEN there is the high-powered agent who gets his clients plenty of work but makes strange errors of bookkeeping. A case in point was that of Felix Young and Noah Beery. Mr. Young secured a job for Mr. Beery. The producer who wanted this excellent actor agreed to pay $2,500 for his services and Mr. Young accepted. However, Mr. Young must have been thinking of some other deal when he told Mr. Beery the terms of the contract.

As he explained it, Mr. Beery was to receive $1,500 and a share in the profits of the picture―and $1,500 was all Mr. Young paid. It seems that Mr. Beery subsequently discovered that the producer had paid Mr. Young $2,500 for Mr. Beery's services and had said nothing whatever about giving him a share in the profits. Mr. Beery, being rightfully wroth, had Mr. Young arrested for divers illegal practices. A jury saw it that way, too, and recommended that Mr. Young be awarded free room and board in the state penitentiary, a sentence that was never carried out because Mr. Young was granted his plea for probation.

A CURIOUS result of the incident was this: Despite the fact that the jury found Mr. Young guilty as charged, and there was no particular reason to think the jury was wrong, there was considerable indignation around the village over the fact that Mr. Beery had taken the matter to court. After all, it was argued in various quarters, Mr. Young wasn't such a bad sort of a fellow and the fact that he had trimmed Mr. Beery, an actor, out of a few hundred dollars was no reason for telling the cops about it. Since when had it become illegal to rob an actor?

A dishonest business manager, if given sufficient leeway, can reduce his client to a state of abject poverty. He can, for instance, advise the purchase of worthless securities—and split the commission with the salesman from whom they are purchased. He can put through padded expense accounts. He can make personal purchases on his client's charge accounts, providing the latter doesn't scrutinize the bills too closely. If he has the privilege of signing checks he can get away with almost anything.

Strangely enough, a surprising number of picture people have entrusted the handling of their personal affairs to irresponsible young men and women who have promptly proceeded to separate them from enormous quantities of loose change.

AT the present moment Hollywood and its environs are suffering from an acute attack of too many and much too smart income tax experts. Income tax experting may not be a racket but, judging from the wails of anguish of the maimed and mangled, it has turned out to be, in several instances, anything but a legitimate business.

In common with a hundred million other Americans, picture stars have never been able to make head or tail out of the federal income tax. Their problem has been more puzzling than average because their incomes are large and their exemptions comparatively small.

Eight or nine years ago several ambitious young men and women undertook to solve the problem for all concerned. They set themselves up as experts in the matter of making out returns for screen artists. They were corking salesmen for themselves and in no time at all an imposing list of celebrities had surrendered their tax headaches to the care of these specialists.

The immediate results were gratifying. The experts charged plenty for their work, but look at the money they saved you! It was worth it. The experts got bigger and better clients. The rescued ones told their friends, who gathered up their checkstubs and climbed aboard the bandwagon. Thanks to these financial geniuses, federal income tax had ceased to be either an expense or a problem. It was just like a dream―but―

CAME dawn―and the awakening. All the headaches that had been handed over to the experts came boomeranging back―with interest at six per cent and appropriate penalties for fraud. It was a great big morning after. A whole trainload of steely-eyed young men came from Washington to Hollywood to see the picture stars―and their books of account. There were investigations, demands for tax―back tax―hundreds of thousands of dollars' worth of it. Two of the most popular experts were indicted by the federal grand jury on charges of conspiracy to defraud the government. Dozens of the most prominent people in pictures rushed into panicky huddles with their attorneys. Many of them were called before the federal grand jury. Some of them were permitted to revise their tax returns and pay large gobs of additional tax. By and large, a good time was had by all.

Maybe the whole business was only a careless mistake, but it seems more likely that the income tax experting business was a great racket while it lasted. All of which, I hasten to state, doesn't mean that there are no excellent tax men in the village. The government didn't indict all of them.

MRS. JOHN JONES, whose husband is an honest plumber―let's not start that argument about there being no honest plumbers―has a toothache. She goes to a dentist. He inspects the ailing molar or bicuspid, as the case may be, and sends her over to Dr. Forceps to have it yanked out. His charge for this inspection and advice is perhaps three dollars―not more than five at the most. Dr. Forceps turns on the gas, jerks the tooth and submits a bill for five dollars.

Gladys Fitzfancy, queen of the box office bets, has a toothache. She goes to the same dentist. He looks her over and fusses around―maybe he tells her to come back tomorrow. Eventually he sends her over to Dr. Forceps to have it extracted. For this sage advice he bills her for a hundred dollars or more. Dr. Forceps, after a great fanfare and tooting of trumpets, finally accomplishes the astonishing dental feat of removing the offending tooth from the lady's jawbone. A few days later Miss Fitzfancy receives a bill for two hundred and fifty dollars―no discount for cash.

I'm quite sure all the Hollywood dentists don't use the same system of cost accounting, but I'm equally sure that some of them make a practice of charging film stars exorbitant fees for their services.

Doctors?

Well, a certain young gentleman not long ago received a bill of $10,000 for the removal of his appendix. Wealthy as he unquestionably is and accustomed to having the harpoons thrown into him from many directions, he balked at that one―actually refused to pay it and suggested he be sued. He wasn't. A compromise was made at a much lower figure, which was still a lot higher than an ordinary mortal would have been asked to pay for a similar bit of surgery.

There was an instance where a medico was forced to turn his patient, a famous director, over to a specialist. In doing so he advised the specialist that he was just a blithering idiot if he charged less than $5,000 for the job. The specialist, an old-fashioned young man, submitted a reasonable bill, to the great annoyance of the first doctor who, no doubt, felt that such a pinchpenny scale of rates might start the movie great to believing you could really be cut open and renovated without having to mortgage the old homestead.

Of course, maybe it isn't all the doctors' and the dentists' fault. There is always this to be said: if it only cost Gladys Fitzfancy five dollars to have her tooth pulled she would probably have felt much worse than if she had left it where it was. Only five dollars for the job! Why, you couldn't even pull a tooth for that, let alone do it correctly. And there are plenty of people in pictures who, if they were billed a mere five hundred dollars for an appendix operation, would worry themselves to death for fear the doctor had left his scalpel in the incision.

THE advertising racket. There's a good one―well-organized, conducted by experts and highly remunerative.

There are a number of trade publications―some powerful and influential, some insignificant little sheets―that either exist or pay extra dividends on the advertising of stars and lesser players or anyone receiving regular salary checks. It goes like this:

The magazine cooks up a "special number." Perhaps it's in honor of Mike Zemansky, the biggest exhibitor in South Dakota―he owns all the theaters. It's Mike's twentieth anniversary out of the glove business.

A fine fellow, Mike, a power in the industry. He deserves recognition, a monument to his achievements. Out go the wily salesmen after the stars. They request a page of personal advertising for this great tribute to Mike. The impression they create is this: Mike's a funny guy, a proud old fellow who takes care of his friends.

He's certainly going to be interested in knowing who remembers him and who doesn't. The only way to pay him tribute is to buy a page in this special number. Won't he be tickled to see your picture on a full page with something nice under it like, "Good luck, Mike?" You bet he will. He'll call his advertising man and say, "Pete, look at the nice thought this fellow has for me. The next time one of his pictures comes to town give him a break―a big break."

You aren't interested? Now listen―if Mike doesn't see your name in this issue he's just as likely as not to bar your pictures from South Dakota. You've got to play ball with these fellows. It's good business.

You still aren't interested? Wait a minute. We've always played ball with you. We ran pictures of you in (pause while card is consulted) twenty-two of our issues last year. We've always shot square with you.

You don't want to? All right, just wait until we review your next picture. Just wait and see what kind of a break you get.

It's a lot of canal water, of course. Mike probably never as much as glances at the pages of paid advertising. But it works―you have no idea how well it works. Thousands and thousands of dollars are spent by film stars every year on this sort of advertising. It's a racket, but they are afraid to offend. It's cheaper to buy a page in Mike's special number, even if it hasn't a dime's worth of advertising value.

A NEW beach club is being organized. The promoters want some prominent names to head the membership list. They call on Reginald Merryweather, a star of the first water. They would be honored to bestow upon him an honorary membership at absolutely no cost or expense to himself. That sounds reasonable to Reginald, so he accepts. Six months later the club goes broke, with a huge deficit. Is Honorary Member Merryweather stuck for his share of the debts? The answer is "yes."

Would the feminine social leaders of the metropolis lend themselves to a racket? How about this one?

They call them showers―same old variety―everybody comes and brings a present. They've spread over Hollywood like Texas fever spread over the cows. They are held for birthdays, betrothals, brides and babies. Imogene is being married. Gertrude says, "I'll hold a shower for you. What do you need most, dearie?" "I could use a complete set of table crystal," says Imogene. Gertrude phones out the invitations with specific instructions. "It's a crystal shower," she says. "We've picked out a set of crystal down at Blink's that we think she'll like and we've decided it would be a good idea for everyone to get pieces of the same set." She neglects to state that "we" doesn't mean Lindbergh and The Spirit of St. Louis. It means Imogene and Gertrude.

But they fall for it―honest they do. They trot right down to Blink's and buy that set of crystal for Imogene, who has money enough to buy herself ten dozen sets of crystal, and heaven help the one who arrives last and has to go for the service plates―the only thing left. And the next week somebody else gives another shower for Imogene and the same set of guests is invited and has to run down and buy something else for the blushing bride.

CHARITY―ah, sweet charity. That's a racket that leaves a bad taste in the mouth. The district attorney's office thought so, too, and is still chasing a couple of bright lads who were getting rich on charity. They would go to some worthy organization and offer to stage a benefit in its behalf. They would either guarantee a definite sum or work on a percentage. The deal closed, they would leap on their bicycles and pedal furiously for the hunting ground of Hollywood.

The average actor, if he has money in his pocket, is a soft-hearted cuss. He is sincerely moved by a plea for starving children, poor devils fighting tuberculosis, suffering of any sort. He contributes gladly and sometimes quite generously. It's a pity that these sharpshooters retain perhaps eighty per cent for themselves and turn over twenty per cent to the charity. Unfortunately, as soon as one phony dodge is exposed, some smart fellow comes along with another.

That Coty perfume racket was a slick one. Just before Christmas a suave young man invaded the studios and contacted the men―stars and executives. He had smuggled in a lot of fine French perfume from Mexico. He was offering it at a third the usual price―great Christmas gift for the ladies. What kind was it? Coty―you know about Coty. He showed them the bottles, Coty bottles with the familiar Coty label. He let them smell. Some of them recognized the fragrance. They bought a lot of it―the young man literally disposed of gallons, at a third of the regular price. When the girls opened their Christmas presents there was no great rejoicing. Some of them inspected the bottles care- fully. Coty? The labels didn't say Coty. They said Cody. The contents didn't smell like Coty, but more like a careless mixture of bay rum, rubbing alcohol and essence of jockey club. Well, you couldn't have the boy arrested for that. Maybe he did say Cody. And nobody had bothered to inspect the labels very closely.

There are dozens of rackets for gaining entrée to studios and stars in order to sell them dozens of articles they don't want and couldn't possibly use. There is the acting school racket―very profitable―that awards the student a diploma which won't even gain its holder a hearing on Poverty Row. Talking pictures have precipitated a deluge of vocal teachers, voice coaches and instructors in every dialect from Siamese to Milt Gross.

I don't suppose all, or even many, of these rackets are native to Hollywood. It's only that the town has a stupendous number of loafers to work them and a positively colossal number of suckers to fall for them.

FOR the benefit of glib-tongued and fleet-footed young men who might be interested in turning a dishonest dollar. I offer the one that was worked on me as recently as yesterday afternoon.

I was not at home―naturally wouldn't be in the afternoon. A messenger boy―just a racketeer, or may be an apprentice racketeer, in disguise―rang the doorbell. He carried a neatly wrapped package. The maid answered.

"Package for Mr. Rogers," said this fiend in human form. "Two dollars and sixty cents collect."

It seemed unusual, but it sounded plausible. The trusting girl shook four quarters and sixteen dimes from the baby's bank and paid the wretch.

"What's in the package?" my wife asked when I came home.

"Package?" quoth I.

She handed it to me. My correct name and address was on the label.

"That's funny," I said―and opened it. I won't keep you in suspense. For $2.60 I had purchased, from party or parties unknown, an empty beer bottle and a badly worn and entirely worthless gentleman's shoe.

![]()

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1930.

The longest-living author of this work died in 1966, so this work is in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 58 years or less. This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse