Photoplay/Volume 36/Issue 4/Father Knows Best

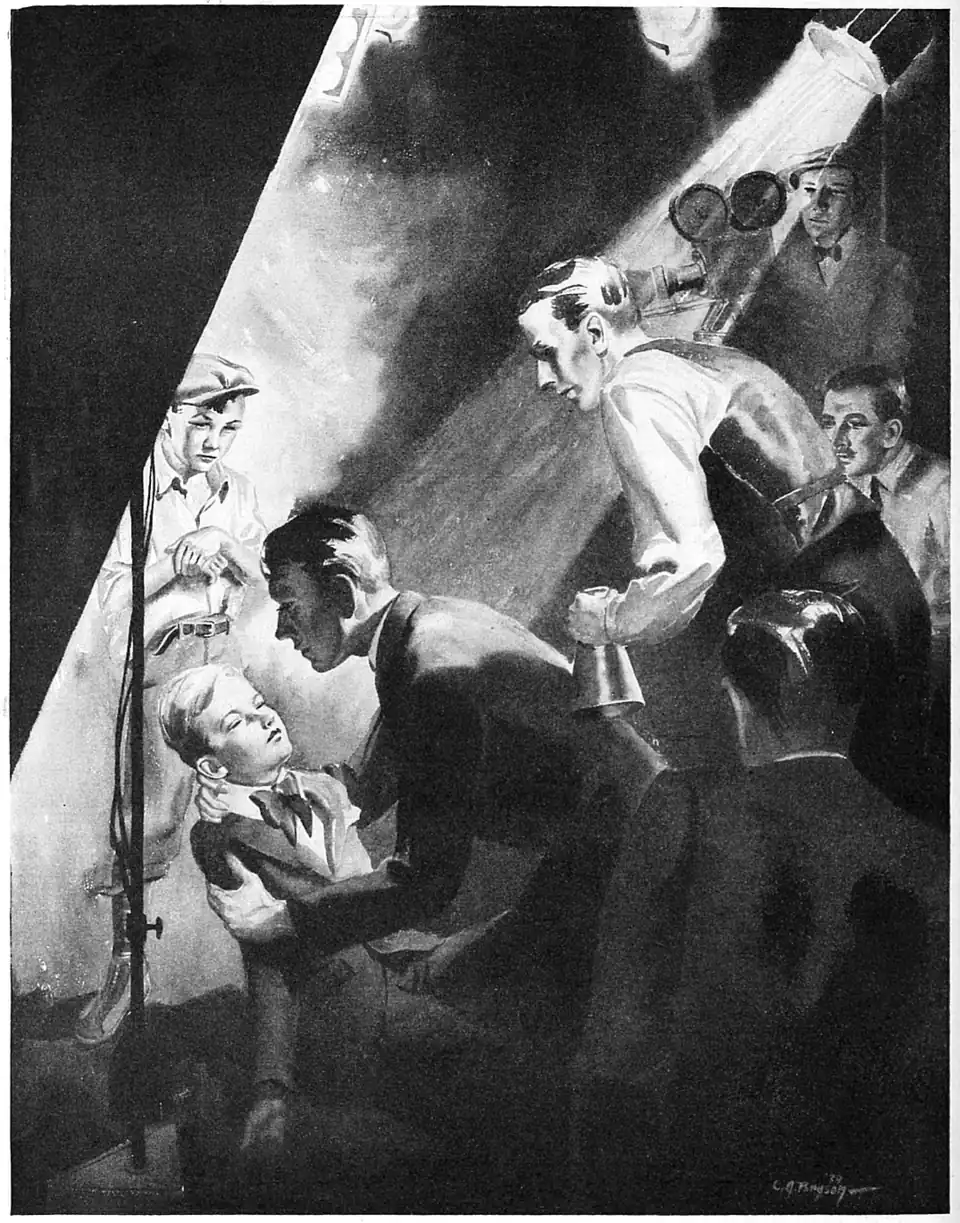

BEFORE anyone could reach him, Johnny's father had skinned down from the rafters and gathered his son in his arms. So light a small burden! So white and pinched a little face!

Father Knows Best

By The EDINGTONS

Illustrated by C. A. Bryson

A different sort of movie story by the authors of "The Studio Murder Mystery"

WHEN Johnny's father went to the hospital to see his first-born, he had difficulty in keeping himself from grinning fatuously, for there was a strange and effulgent swelling inside him. He felt like he used to in church, at Christmas time. He felt set apart, someway, and a little scared.

Of course he knew that Johnny's mother had wanted a girl, and that she had set her heart on calling her Patricia... such an elegant-sounding name, implying wealth, and position. If he had thought that Johnny's mother still cared what sex their first-born happened to be, after she had felt its funny, little fuzzy head, he would not have suggested that she call it Pat—short for Patricia. Johnny's mother had not thought it funny. Instead she had snapped peevishly.

"Call him Johnny... call him anything... I don't care!"

The way she said "Johnny" made Johnny's father think of a stray puppy. He felt like putting the baby's small head, with a protective, sorry feeling.

And so, from the day of his birth, Johnny's parents were of two minds concerning him. His father's lips were closed straight away by the doctor, warning that his mother's heart had been strained by the birth, and that a shock might kill her.

Johnny's father put a wall about his own heart. He went on earning the living, leaving Johnny to his mother's care. Sometimes he thought Johnny might be dead when he got home. He knew that babies do swallow pins, and fall downstairs, if they are not watched, when mothers sit absorbed in novels. But miraculously Johnny lived on, and miraculously, out of his ill-tended and colicky infancy, came a wistfully beautiful little boy.

WHEN this beauty came to his mother's eyes, she changed in her attitude. From what she had been, she became the most careful of mothers. Johnny's small head was brushed until it fluffed into a mass of shining curls. She stopped calling him Johnny, and one night when his father greeted him as usual―

"Well, how's Johnny boy?"

She exclaimed impatiently,

"Don't call him Johnny! I hate that name! Such a common, ordinary name! I have renamed him Marion!"

"That sounds like a girl's name!" protested Johnny's father instantly.

"Men are named that, too. He's going to be Marion Glendenning, and he's going to have his name in fan magazines, and over theaters... and have his own dressing room... and contracts!"

She spoke dreamily, her eyes looking into some picture of her own. When Johnny's father made an explosive sound of wrath, she turned pale, and pressed her heart, but repeated with weak-voiced tenacity:

"Yes... Marion Glendenning!"

"Marion Glendenning!" he mimicked disgustedly. "That's a hell of a name! How do you get that way? What's the idea? Ain't my name good enough? It's the name you married me by, and by God it's the name my kid was born under! He was born Brown, and Brown he's going to die!"

|

|

| His mother rechristened him Marion Glendenning and taught him it was vulgar for boys to fight |

To his father he was always Johnny Brown, a real kid and not the "little prince of pictures" |

JONNY'S mother shivered away from him in distaste.

"Do you have to shout and curse?" she asked scornfully. "If you'd behave like a gentleman, I'd explain to you!"

"I don't know anything about behaving like a gentleman, and I don't want to. I'm trying to act like a man. Go ahead and explain, but it'll take a damn lot of explaining to get that fool name over to me!"

"I guess you must be blind. If you weren't I wouldn't have to tell you why. Marion was made for pictures! Everyone else sees it. They all tell me I'm silly to let you stand in his way... and I have to take it from them... how you, his father, working right there in the studio, won't lift a hand to better your own child."

The man went suddenly, coldly calm.

"Let me get you straight," he said quietly. "Are you trying to get me to say you can put Johnny in pictures?"

"Yes, I am," she said, meeting his cold eyes defiantly.

"Well, it won't do you any good. You know how I feel about kids in pictures. I've seen a lot of 'em. D'you think I want my kid going to a sanitarium with a nervous breakdown? D'you think I want him to be wise to everything in the world... spoiled and petted and pampered, before he's got a chance to know what life means, or what it's all about? Not by a damned sight! He's going to grow up like a normal kid. He's going to go to public schools. He's going to get his face dirty, and his shirt torn off him. He's going to be real. He's not going to be a spineless, egotistical little snob! If he wants to go into pictures after he's through high, I don't care. He ought to know his own mind by that time, and he can make a lot of money, and get a lot of good things out of life from the openings he gets in a studio. But I'm going to let him decide when he's old enough to know what he's doing!" Then Johnny's mother got to her feet with angry, red spots burning in her cheeks, and with fury blazing in her eyes.

"You men! You make me sick! I'd like to know what right you've got to stand there and say what's going to be done about my child! Yes... my child. A lot you did about Marion's coming into the world! Your son! He's mine. I suffered for him and you're not going to cheat me out of what I've dreamed for him... you're not!"

SHE was sobbing now, hysterically. She had gotten very white. Johnny's father said quickly,

"All right. I won't stand in your way, but don't expect me to help you. You know how much pull an electrician's got in a studio like Superior Films! I couldn't even get you in the front gate!"

"You don't have to! I'll never ask you to help me. I know better! All I have to do is show these..." she bent swiftly to a drawer in her dressing table and brought out a sheaf of photographs, which she held out to him. "Here... these are all Marion needs to get him in! He's already signed up for work at Universal and at Paramount, and today I've an appointment with Morris Keppel. I guess you know who he is! Casting Director at Superior Films, that's all!" she finished triumphantly.

For answer Johnny's father said only:

"How'd you get these pictures? I know what things like this cost."

"Just like you to stand there arguing over the cost, and not caring enough to even look at them!" she burst out bitterly, and flung herself, sobbing, on the bed.

Slowly Johnny's father opened the folio, and looked at Johnny, naked as the day he was born, wearing a cute little quiver of arrows; Johnny in diminutive golf togs; Johnny at the wheel of a new model sports car; Johnny looking out at the world with all the wisdom of all the vamps in moviedom; with all the coyness of a Wampas star; with the poise and assurance of screen maturity...Johnny at five years old!

HIS father wondered if this were really his child, and he marvelled at the mother's adroitness in training him to these expressions.

"So! You've already made a little nincompoop out of him! Trained him like a performing dog to do his tricks! D'you suppose for one minute, he knows why he's looking like this... or this... or this? And you're doing it so you can sell your child's body, and live off the fat of the land! You know what I'd call you if anyone asked me? A maternal prostitute!"

Johnny's mother screamed, and covered her ears.

"That won't do you any good. You'll hear me to the end," said Johnny's father, and ripped the photographs across and across.

"And that won't do you any good!" cried Johnny's mother, sitting up in bed, and laughing wildly. "I can get dozens more! I didn't have to pay for them! Mr. Green was glad enough to let me have them when I said he could use Marion for posing in some art studies.

"WELL, you've beaten me. But get this! You're not to use one penny of that kid's money on the house. Understand? I can keep a roof over my family's head. I'll do it without my kid's help!"

Johnny's mother ended the argument by fainting, and this time it was a genuine swoon of emotional exhaustion. Her husband sat rubbing her wrists and applying restoratives, knowing that so long as this woman was his wife, and the mother of his child, he'd have to take care of her. So long as she was going to faint every time he crossed her, he would have to give in to her wishes. So, silently bearing his burden of sorrow, he gave up his son. From that day he lived alone, going to the studio, and working... coming home and eating... going to bed; saying little, and turning his words and his thoughts inward.

Sometimes he wondered how his wife had the strength to go about to the studios... miles apart... in the heat of summer, with Johnny in one hand, and a heavy package of clippings and photographs in the other; climbing on and off crowded buses; filling her lungs and the child's with the poisonous exhaust of the jammed boulevards. Yet she came home and sat way into the night, too tired to get his dinner, but bending her frail back patiently over Johnny's exquisitely hand-tailored little garments. He had no answer to this, except a shrug, and the realization that women were funny.

He lived in dread of the day when he would have to tend the lights over Johnny's blond, Dutch-bobbed head, and when, in the presence of his fellow-workers, he would have "to eat his words..." for had he not, with them, made disgusting remarks about various child stars who paraded beneath him, mimicking grownups, and grown-up emotions, and going about their pathetic little ritzy ways? He knew he would feel like a knife in his heart the silent, but none the less sentient, contempt of his colleagues for his own spineless self!

AND now days came when Johnny's father seldom saw his little son. One afternoon, coming home early, he met Johnny returning from the private school he attended. What a skinny, delicate little fellow he was! Pipe stem legs. He slumped. There was the wrong kind of a slant in his chest, and where was the ridiculously bursting little stomach most small kids possessed? He was about to reach the boy, when a raucous voice was hurled down from a tree-top across the street.

"Hey... pretty face! Been for your permanent? Did you get yourself a lipstick, too, mama's doll baby?"

Did Johnny's father imagine that the pipe stems, marching ahead of him, quaked?

The owner of the taunting voice shinned down the tree and tore across the road.

"Dare you to fight!" he challenged, and danced up and down with balled fists.

Johnny retreated, getting pale. He threw his arms up about his head in an instinctive protecting gesture.

"Oh, Micky, let me alone! Please don't, Micky! Please don't touch me!"

"Why not? I know, you poor little sap! You're 'fraid you'll get a mark on your lily white face! You poor cream puff!"

"But, Micky, I have to work tomorrow! Oh... Micky... please...."

Johnny's voice rose to a wail, and he fled, with Micky in pursuit. Johnny's father let out a roar and, overtaking the belligerent one, hooted him back across the street. "God Almighty!" he breathed feelingly, seeing his son's tear-stained, frightened face. Then he took him by the arm and tried to tell him things. Boy things and man things... about not being a coward, and learning to stand on your own two feet, and never running―growing into a man among men... but he gave it up when Johnny turned his great, wistful eyes upon him, with now a look of baffled misery in them, and said:

"But daddy, mother doesn't want me to fight! She doesn't want me to be coarse and common! She wants me to be a gentleman! And anyway, it will kill mother... just kill her, if I ever get into a vulgar fight! She'll die!"

"Who told you that?"

"Mother told me herself! You know, she's slaving her life away for me... just to make me famous!"

That was the night Johnny's father sat at the lonely kitchen table tipping up a bottle until it was empty, and he was sodden. That was the night Johnny's mother decided the man whose name she bore was coarse and common, and not fit for association with herself and Marion Glendenning. He was brutal and uncouth, unappreciative, and unwanting of the finer things, and indifferent to his only child's welfare. That was the night she flayed him scathingly, and he in turn, loosed his drink-fumbled tongue in stuttering, but none the less stark truths upon her.

After she had fainted, and he was mechanically doing those things he had learned by habit, he cursed unfeelingly over her prostrate form, for the first time.

A portentous silence now hung over the house, and out of its bitterness came the inevitable parting of the ways. Johnny's mother divorced Johnny's father and moved into a smart flat on Hollywood Boulevard. She legally took the name Glendenning.

And then, through sheer persistence, coupled with Johnny's own appealing beauty, she got him a five year contract to star in child pictures at Superior Films.

JOHNNY'S father had no need to work steadily now. He seemed to lose his morale, and took jobs only when the notion struck him. He disappeared for days, and people said he had gone off to drink, but no one ever saw him intoxicated. He was so far away from the select world into which Johnny had gone, that he looked upon the little star, Marion Glendenning, as upon a small stranger. There was one scene out of the past, that still kept the tie between them... and often and often the man re-lived it. He had been telling Johnny stories, about going camping and doing boy things in the woods. Johnny had listened, spell-bound, his eyes shining.

It was when the child burst out excitedly, "And oh, daddy, next summer can you and I go to the mountains and build really camp fires? Can I build one, myself, daddy?" that his mother came and snatched him away, exclaiming,

"Now I suppose he'll go out and try to set fire to himself in the backyard, and get himself filthy dirty! I suppose you think it isn't any work to keep him clean... his head shampooed and his nails done? A lot of help you are... trying to make it harder for me all the time!"

She said a lot of other things, and finally Johnny screamed. He raised his small fist and shook it in a familiar, trained gesture. His face began to jerk and grimace like a miniature Lon Chaney's, but the tears and the outraged little voice were real, when he cried hysterically,

"Stop it! Stop it! I won't have you bawling the tar out of daddy!"

THREE years after Johnny's mother signed Marion Glendenning's contract, Abraham Rosenthal lent his advisory mind to the kid series. Something was wrong with them. Exhibitors were getting cold on them. The President of Superior Films, and the director of the kid series, Jim Stoddard, sat side by side, watching Marion Glendenning on the screen. Rosenthal said little but grunted repeatedly during the showing of the last made film. When it was over, he got to his feet ponderously.

"VELL, I do not blame the exhibitors. If anybody tried to sell that to me I vould be disgusted. If that film gets out to the public that boy is ruined. Killed deader than a mackerel! He iss too big to act like a baby! He iss too skinny! He acts all the time like he has a fear complex about everything! He looks like a valking skeleton. Ve vill be attacked by the Cruelty to Children people! How long iss his contract yet?"

"Two years to go, and one hundred thousand dollars still tied up in that series written by the foremost author of child books in the country," returned Stoddard glibly.

Rosenthal groaned.

"Vas all those stories about a sissy? Vell, ve got to change them! Take that long-haired poodle to the beach and get him tanned up. Fill his stomach for vonce, maybe. I vill get Miss Hunt to re-write those stories. Ve don't care vat the author says. It's got to be done, or ve are ruined! Ve put some real American boy stuff into it. You know. Boy Scout stuff. Fights!"

Stoddard laughed,

"My God, Rosie, you know his mother! She'll drop dead!"

"A mother like that should to drop dead! Say, did you ever see my Izzie? He could lick that poor liddle nodings vid vone hand tied. Vat you think he does when he sees that picture? He throws rotten eggs, I bet! Vat for do ve make kid pictures? For the kids, ain't it? Vell then, ve got to give them a hero they don't vant to bust in the nose! I tell you. Ve vill put him in some fights, and then've vill make an aviator out of him. Send him up in a plane. That's good stuff. Ve vill advertise him as a young Lindy. Ve put some punch in that stuff, and maybe too ve save that kid from starvation, ch?"

"Oh, I don't know, Rosie. Maybe it isn't as bad as that. Some kids are just naturally skinny. Maybe he's the skinny kind!"

The President only grunted skeptically.

WHEN Stoddard told Johnny's mother, she stormed and wept and all but fainted.

"Take it or leave it, Mrs. Glendenning," said Stoddard.

"But we've got a contract! His contract doesn't call for fights, and going up in aeroplanes! Rosenthal can't break a contract! Nobody can break a contract! It's all written down!"

"What has been done, can be done," said Stoddard cryptically.

"But we all agreed he was to be the type he is... not coarse and vulgar! He's not that kind of a little boy!"

"My dear little woman," said Stoddard wearily, "you've stood in Nature's way long enough. You seemed to be getting by with it pretty successfully, too. But now you've bumped up against something different. Mr. Rosenthal saw that last picture today, and it's thumbs down! You've been here long enough to know that what he says... goes... and that what he decides is pretty nearly always right, and square shooting! Kid stuff isn't so strong these days that you can afford to sue Rosenthal. Anyway, the first thing you know Marion's going to be in the gawky age where he's no good for pictures. You'd better he saving for a rainy day, and grab what you can get now and you know it!"

Full well she knew it, as every theatrical mother knows it! Just when their long hours of patient striving have been rewarded, and they settle down, relievedly, to enjoy the fruits of their labors, looms the gaunt spectre of the lean years... the years when milk teeth come out, and leave ugly gaps in pouting little mouths; when dimpled arms and legs shoot out overnight into string bean-like tentacles that wind and twist and wriggle without reason. It was this period that Johnny's mother had been trying to postpone by every means possible short of actual abuse.

AND now Stoddard had named it to her, and in so doing had brought the thing close, to stare at her through the night! When Johnny chafed her wrists, and held the smelling salts through her dark hours, she saw, in a panic, how the baby softness of his hands was leaning away! She had a hard night, but she was on hand next day, for work.

"Now, before we get Marion's hair cut, we'll start him in this picture as a mother's darling. We pull the fist fight, and the victor drags him to the barber shop. After that the kids get together and build an acroplane. We're going to get one of the big plane factories to send us miniature parts that can be assembled by the kids on the screen. Maybe you think that won't go over with a bang!" said Stoddard enthusiastically.

Of course it was Johnny's ancient enemy, Micky, who was the little extra called in to play the bully. It would be! Johnny's knees repeated the old-time tremolo when he saw him. The starch, what there was of it, was taken out of him before the boys ever went to the mat. He stood scared stiff. His stomach was a heavy cold lump inside him. His heart pounding so it vibrated his little Lord Fauntleroy ruffled shirt. Micky puffed out his chest and danced about, fists balled, as he used to do, keenly anticipatory, and sicking Johnny on to fight with the same old raucous jibes!

What was it in Johnny's subconscious mind that rose up and clutched his vitals... bound his arms and his chest like an iron band? A well-learned lesson:

"If you ever get into a vulgar fight, it will kill mother... just kill her!"

Helplessly he looked to his mother for aid, for some release, but there was none. He turned his big eyes on his director...

"Go ahead, Marion! Snap into it! Do your stuff now. Give him a sock in the jaw!"

"I can't fight, Mr. Stoddard!" Johnny mumbled shakily. Cold sweat on his forehead. Cold sweat in the palms of his helplessly hanging little hands.

AND there was cold sweat on the brow of Johnny's father, astraddle a beam up over the set, minding the light that shone down on Johnny's head... down on the little weakling who was his son, and his first-born! Johnny's father leaned far down, trying to send to the little hoy something of courage and help.

Micky yelped impatiently.

"Get going! What's the matter? Scared stiff, ain't you, like you allus wuz! Sissy! Fraidy cat! You poor little scrap of nothin'..." for it didn't matter to one of Micky's make that he talked to the child star of Superior Films. He had never been on the lot before, and studio caste was an unknown thing to him.

"IF you'd ever been fed anything but soothing syrup, you'd have some guts in you! I'm damned glad my maw didn't do that to me! I'm damned glad your maw wasn't my maw!"

At that, something inherent in Johnny made him go forward and raise awkward, ignorant fists. Micky had insulted his mother. Men fought for that, he knew.

"Atta boy!" yelled Stoddard instantly, spurring him on. "Atta boy! Snap into it! Sock him one!"

Micky eagerly took the words unto himself, and shot out a grimy, hardened fist. He caught Johnny under the point of the jaw. Then the floor rose up and smacked Johnny on the back of the head.

Before anyone could reach him, his father had skinned down the rafters and gathered his son in his arms. So light a small burden! So white and pinched a little face! Only parents know the hurt of that!

"Hospital," growled Johnny's father, and made for the stage door, the entire crew following, brought up in the rear by Micky, blubbering loudly,

"I didn't mean to kill him, Mr. Stoddard! Honest to God I didn't!"

Johnny's mother ran after, emitting hysterical screams. She tried to push Johnny's father out of the hospital, crying, "You put him down! Don't you touch him! You let him alone!"

But the father shouldered her, unanswering, out of the way. Tenderly he put his son down on the bed, and turned to the nurse.

"Get the best doctor in town. If you want anything―money, or anything... let me know."

"We have the best doctor on call all the time, you know, Mr. Brown, and the studio pays for it. But I'll keep you posted. Now everyone go away. The doctor will be right out, and he'll want to examine him immediately."

Johnny's mother tried to talk to Johnny's father in a shrill, excited voice, but he walked past her unhearing.

NIGHT settled down on the busy place. From far out on the back lot great sweeping rays of light raked the sky like comet tails, and plunged back toward the earth. Somebody was shooting night stuff. But in the studio grounds proper it was very still. Lannigan, the night watchman, walked past the hospital, making strange Gaelic prayers for the fate of the little fellow who lay there, and MacDougal, the night gateman, minded a time when his own girl had lain in that same bed, sore distressed. Once he went to the hospital gate and inquired after the little actor.

"Just the same," said the nurse. "You never can tell about these concussions. He might stay in a coma for days."

"D'ye ken whether or not it will be fatal?"

"I hardly think so. But there's always a possibility. Everything's being done."

MacDougal saw Johnny's father, walking up and down the gravel paths. He had a great sympathy for the man. He would have helped him if he could. But even he could not see into Johnny's father's heart, reproaching itself that he had allowed this thing to happen to his child. Over and over an old refrain echoed in the father's cars:

"If you ever get into a vulgar fight, Johnny, it will kill mother, just kill her!"

What had his boy thought when he stood there, afraid? What had he thought when the world reeled and he went down under Micky's fist? Perhaps psycho-analysts would tell him Johnny was even now laboring under the black pall of that lesson, drilled into his subconscious mind from infancy... and that it was helping to retard his return to consciousness!

"God, it ain't right! It ain't right my kid should believe a thing like that! Maybe that's what he's thinking right now. That his mother's dead because he got into a 'vulgar fight!' I got to reach into him someway and tell him it isn't so!"

He went in, and asked the nurse to let him see his boy. "For just a minute," she agreed.

The father went down on his knees and held the skinny little claw in his own hot, rough hands he looked long at the deepening blue hollows where the long lashes lay.

"Johnny... your mother's not dead. And you mustn't believe you could ever kill her... no matter what you did! If she ever dies, it will be God that takes her. Little boys can't do things like that!"

Looking at Johnny made him remember his own little boyhood. Its bewildering, wondering moments, when his child's brain had become be-mazed in things it could not understand. Long passages from the Bible, that had, when he sat and squirmed miserably in his Sunday go-to-meetings, seemed impossible of comprehension or meaning, began to clear up for him now. One mandate kept recurring in his mind: "Thou shalt not put other gods before me!"

That was what Johnny's mother had done. She had made a god of fame, and set it up like a Golden Calf, and prostrated herself before it! If Johnny's mother died of the shock of what had happened, it would be that God struck her down in his wrath. He must find words to explain to Johnny when that time came... and still spare his mother!

TWO things happened on the third night after the accident. One was that Johnny regained consciousness, and the nurse dared to relax her vigil, and go to her room for rest. The other was that Marion Glendenning dis-

appeared. Disappeared as finally as though the earth had swallowed him up. Unbelievably he had been abducted from out a place whose every entrance was guarded! It was a distracted nurse who sent out the news.

"I only took forty winks! I never heard a thing!" she protested.

The studio grounds and the nearby district were thoroughly searched, for fear Johnny had walked in his sleep. He was not found. It was a plain case of kidnapping.

Johnny's mother went into hysterics. She fainted. Recovering she rushed to the telephone and called up all the newspapers.

"TO think of anything like that happening to Marion! With a watchman and a gateman here all night, and everything locked! There's something back of it! It's a plot... a plot!" Her voice rose high, and higher. Isadore Cohen, Production Manager, whose nerves were none too strong, hugged his head against that shrill voice.

"Please, please, won't you to calm down vonce? Ve vill do all ve can. Vait until Mr. Rosenthal gets here. Ve vill put detectiffs to vork! Ve vill spare no money... I tell you vait and I vill call Rosenthal right offer!"

"You know something about this, Mr. Cohen! I can see you know something more than you are telling!"

"And you haff the nerve to say that to me, when've stand to lose a hundred t'ousand dollars because of your boy being kidnapped! You haff the nerve! Don't screech no more. I vill get Abie right avay!"

"You just bet you'll get Abie! Something's got to be done about this! It must be in all the papers... everybody must join in the search. It must be broadcasted right away!"

"The newspapers! Broadcasted! Mein Gott, and right after that Hardell murder mess! Oi, is it ruined you vant us to be!"

Just now Abraham Rosenthal, followed by a gang of reporters, entered. Mr. Rosenthal had learned a great deal through the Hardell case. He knew that it was better to talk to reporters than to create an atmosphere of mystery by "refusing to make a statement!"

"NOW boys," he said, handing out his costly cigars with a generous band, "here is the little boy's mother. I vant you should get the whole story from her. Ve vill giff you photographs and efferything. The more people vat know about this business, the quicker he vill be found."

t was three hours before they got away from Mrs. Glendenning. They had taken at least fifteen poses of her, clasping some article of Marion's to her bosom, and staring out with wild, anguished eyes.

"Some tragedy queen, Mrs. Glendenning," one of the newsmen had dared to say. She was pleased by the compliment.

"Oh, I know my boy gets all his talent from me," she admitted, "but I've always found my happiness in slaving for him! I've given up my life for him, gentlemen!"

It was not until one of the gang suggested diplomatically that they had better bring their stories to a close by the statement that, "Mrs. Glendenning, mother of the famous little star, is prostrated by the news, and under the care of a nurse in a sanitarium," that she subsided.

"Yes... yes... I am prostrated. Simply prostrated!" she moaned. The nurse took her cue and led her away to bed.

"MEIN Gott, if only Smith vas here!" deplored Rosenthal, when a week's combing the country failed to reveal the whereabouts of the little prince of pictures.

"You act like this man Smith was the only detective in the world with any brains! Why don't these other men get busy, I'd like to know!" exclaimed Mrs. Glendenning. "If you were interested in finding him, you'd offer a reward! I'll bet that's all the kidnappers are waiting for! Did you ever think of that?"

"Yes. I thought of it. I haff decided to do it. But you must remember, Mrs. Glendenning, already ve are losing money. If that boy iss not found, just like that all those pictures he vas in are vorth nodding! Ve cannot finish the series. Ve paid a big sum for those stories. Ve cannot afford to lose it! It vill come very close to bankrupting us! Haff you effer thought of that, I ask you?"

"What difference does that make? You can always get money for more pictures! Men in Wall Street are just crazy to buy motion picture stock!"

"Hm... vell . . . mebbe..." said Rosenthal dryly. "Anyvay, 1 make an offer off ten thousand dollars for the return of the boy. Now go ahead and phone all the papers!"

And the days went on, even after the reward was offered, and yet no word of Marion Glendenning came from the numerous sources of the various rescuers. Once, when Mrs. Glendenning came to him seeking some new angle to throw into her daily story to the press, Rosenthal got up and pounded his desk furiously.

"I vant you should stop talking to the papers! Vat good is it doing? Do you see me going around posing for those reporters, and giffing out interviews? No, I am putting my mind on some vay to locate that boy of yours! If my Izzie he gets himself lost from his mother, you know vat she does right avay? No? Vell I tell you. Right avay she goes to the synagogue and prays that he vill be returned safe and sound! How do I know? Because that is the vay my Rachel is by her children! Maybe you could pray a little? I got great faith in prayers by the mother. Now get out!"

But lost fortunes, and prayers, and countrywide search, were alike fruitless. The only man who could have thrown light on the mystery was MacDougal, the gateman, and he swore solemnly that he did not see anyone take Marion Glendenning through the gate.

THERE is a hilltop running back from the sea, where vineyards bring their purple fruit to sweetness every year, and running along the hilltop is a road known as the Empire Grade. It is an old, sandy wagon road, and automobiles do not go there. Below the hill lies the little town of Santa Cruz, a day's travel north from Los Angeles. Summer brings_many visitors to this district, but the old Empire Grade is an out-of-the-way place, and only old Tony, and a few other early Italian settlers remain there. It was an evening in spring, when a new moon was rising in a pale lavender sky, that Tony heard his dogs give tongue and he went out to stand under the grape vines on his trellised porch to see what was up. He saw a man staggering toward his house, with a burden in his arms. He knew the man. He

had given him shelter off and on for years. But now the visitor did not waste time in greeting.

"Open the door, Tony. This is my kid. He's been hurt. Go down to town and get a doctor. I'll have to have your wife to help right away."

"Va biene! Maria! Maria!" called Tony, and the man stepped aside for the buxom Italian woman, who bent over the child with little indrawn sounds of sympathy.

"TONY not a word to anybody! Tell the doctor you want him for one of your kids! But make him come. I can pay him well! But not a word! You understand, Tony?"

"Si... si..." returned Tony impatiently, hurt at being doubted.

It was after the doctor had come and tended Johnny, that his father told the two other men his story. He saw by their eyes that they were with him, and would stick by him. When the doctor rose to go, after draining a glass of Tony's good wine, and eating a big slice of thick Italian bread and white cheese, he held out his hand.

"You can count on me, Brown. The boy's all right. He'll get good nursing from Tony's wife."

All that, now, was months past. Summer had come and autumn, and the emerald green fruit had ripened, and gone, in great numbers down Johnny's greedy mouth. Tony's boy, Angelo, and Angelo's small cousins, let into the secret, had helped to guard the little prince of pictures. To be sure, promise of a generous reward aided their natural childish love of the mysterious. Unknown to themselves they had metamorphosed Johnny. He was as brown as any of them. He was as fleet-footed as any of them... and... as hard-fisted! Even now, as his father leaned against the cabin door, watching, Angelo dared him to fight.

"Coma here, you keed, you! Let's maka the grand fight!" No hesitation now, Johnny leaped at him.

They were in the dust. It was Johnny who sat astride of the other's back and called, "Holler quits! Angelo! Holler quits!"

BUT the smile of pride left the man's face as quickly as it had come. When Tony walked up, he said, "Well, Tony, the time's come. My boy's ready to go back!" Tony shrugged.

"I thinka you one beeg damn fool to take that keed back. They maka the sissy out of him again, you see! I tella you straight!"

"He's got a mother, Tony. She worked hard for him. He's all right, anyway. He's a different kid now. He'll start out different!"

"You going, too?"

"Just to take him down. I'll come back and go shares with you, like I said. I'll get that truck while I'm there. Yep. I'm coming hack. The kid might need me... and this place again some day. He might come back..." the man's voice broke. He shoved himself abruptly off the door jam and walked away.

"God damn!" swore Tony with soft emotion, "God damn! I thinka he breaka his heart over that keed for sure!" Then he shrugged. "Va biene... the keed he gotta the love for his dad, all right. He come back some day, you bet!"

IT was night when they rolled down Cahuenga Pass, and into Hollywood. As they stopped for the traffic signal at Highland and Hollywood boulevard, Johnny looked eagerly at the old familiar lights.

"Gee, dad, there's something about them, at that! I guess I think a lot of Hollywood, after all!"

"Glad to get back, kid?"

"Uhuh! Of course, I'll never forget the ranch, and the kids, and you... and everything... but..."

"That's all right, son. I only want you to be happy. Now let's see, you lived somewheres on Melrose... wasn't that your last place?"

"Yes. But I guess mother's had to move, dad. That place cost an awful lot of money, and maybe she couldn't afford to keep it."

"Oh, I guess they kept on with your salary. Rosenthal's a decent sort, and it wasn't your mother's fault I kidnapped you!"

"Gosh, dad, you sure did that slick! What gets me is about old Mac! He's got eyes in the back of his head, we used to say. I never knew him to miss anybody going in or out, before!"

"You're wrong about the eyes in the back of his head, son," said Johnny's father with a chuckle. "I know he hasn't got any!"

"How do you know?"

"Because he had his back to me when I walked out!"

"Gosh. Say, did he do it on purpose, or did it just happen?"

"Here's your corner, boy," evaded his father hastily then, and began slowing toward the curb.

"Golly... say... I guess I'm excited about being back! Why, dad... say... there's old Beany! The policeman on our beat, you know!" Before his father could stop him, Johnny was calling shrilly, "Hey Beany! Bcany! It's me! I'm home!"

And then Johnny found himself lifted out bodily and set down on the walk before he could say Jack Robinson, and the car that had brought him was breaking the speed limit down the street. The policeman grabbed his arm. It had taken him a moment to recognize, in this sturdy, upstanding lad, his little friend of the studios.

"Who brought you? Who was that man?" he demanded excitedly, blowing his police whistle, Johnny snatched it from his mouth at first sound of the blast.

"That man? Oh... well, he was just a man I knew, Beany."

"Did you get his car number?" demanded the policeman.

"Why... it's just a number. Just any old car number, Beany!"

"Say, little feller, what's wrong with you?" Beany shook Johnny until his head wobbled, "You act like you was drugged! Did he give you anything?"

"I'll say he did! He gave me the time of my life! And say, Beany, it won't do you police guys any good to third degree me, because I'm never going to tell who he was, and I'll take the secret to my dying grave!"

"Well... fer crying out loud," said Beany helplessly, and scratched his head.

"Beany, does my mother still live there?"

"Saw her come home 'bout an hour since."

ABOUT two weeks later a little group sat at a private preview of Johnny's latest picture. There was Stoddard, the director, and Abraham Rosenthal, and a few select others, besides the star and his mother... and his best friend. They watched on the screen one of the doggondest best fights that ever went on a film, and every scenario writer knows what a good fight will do to put over a picture.

"Look at 'em, Rosey! Look at 'em! I tell you the fight in 'The Spoilers' can't hold a candle to it for spirit!" He chuckled, and slapped his leg. "Wait until that bunch of exhibitors gets an eyeful of this! Why, say, they'll eat it up and come back for more!"

Johnny's mother sat stiff and dry-eyed through the film. It was hard for her. She had not yet quite become accustomed to this new little boy who whistled and shouted through the house. And yet she was trying. Already she had learned to repress the too numerous "don'ts" and to keep silent when Johnny and Micky, now bosom pals, engaged in practice battles in the backyard. Now she closed her ears to Micky's gleefully chortled:

"That's a Hell of a good fight we put on, kid... if we did do it ourselves! Wait until my old man gets a squint at that! He's just naturally goin' to swell up and bust, he's going to be that proud!"

"So's mine!" whispered Johnny so that only Micky's grimy ear heard.