Photoplay/Volume 36/Issue 2/My Boy Buddy

My Boy Buddy

By B. H. Rogers

Editor of The Olathe, Kansas, Weekly Mirror

Photoplay at last finds the father of a screen star who tells his own story

The future Paramount star at the age of four, a daring equestrian on his own Shetland pony. In those days Buddy hoped to be an editor like his dad when he grew up.

"NAMING the Baby" was the momentous question in the home of Mr. and Mrs. B. H. Rogers, Olathe, Kansas, on the evening of Friday, August 13, 1904, following the arrival of an eleven-pound boy. Our home was then on the west side of the public square, where now is located one of the largest buildings in Olathe, housing a garage and automobile sales room.

Although it was the 13th—and Friday—there was no thought of bad luck, although it was a mooted question whether the plump baby should be named for me, Bert, Junior, or Charles Edward—Charles for a deceased brother of mine and Edward for his maternal grandfather, Edward Moll. The latter was finally chosen but it was never used. As baby, boy, and young man he was never called anything but Buddy, so the name was given to Buddy's brother, who came six years later.

As to the origin of the name Buddy—a sister, Geraldine, almost three, really named him thus, which was as near as she could come to the word "brother." The name stuck—he never was called Charles until after he had finished high school, when, on entering the University of Kansas, he was obliged to enroll as Charles. But that was all we ever heard of Charles during his three years there until he was made a star in pictures. Then Paramount officials thought Charles would be more dignified, as he grew up in pictures—but even they couldn't make it "stick." His fans would not have it any other way.

Here is the whole Rogers family outside the Olathe home. From left to right: Mr. and Mrs. A. E. Moll, Buddy's grandparents; Buddy, his mother, his father, his sister, Mrs. John Binford, of Lincoln, Neb., and his younger brother

To my absolute knowledge, not once in my life have I addressed him as Charles—always Buddy. It may have been rccounted before, but a wire came for him to Olathe, addressed to Charles Rogers, and I sent it out to the country to a cousin of his for delivery. His diploma at graduation from High School was issued to Charles Rogers, but all his teachers with one exception called him Buddy.

Much of his rearing was in the office of my paper, The Olathe Mirror', the oldest weekly in the State of Kansas. It was established in 1857 and has never missed a single issue, though, during the war, guerrillas plundered the town. The office was wrecked, some of the machinery destroyed and much of the type thrown out an upstairs window.

There were always bills to distribute—and I paid him the same as anyone else for handing them out, so he usually came to the Mirror office the first thing after school. He spent all day Saturday here, even before he became the regular devil at nine years of age. As devil he started fires, swept out, carried coal and kindling, ran errands, delivered Mirrors', as well as The Daily Kansas City Star. He had a route of sixty-three customers.

During school vacation Buddy put in full time and his pay was $1.00 for a full day. Then, as he learned to run the job presses and the big cylinder press, he was paid more. During his high school years, he contributed to the Mirror a column of high school news weekly and, during vacation of the last two years, he assisted me in the front office, getting news, advertising, keeping books and doing the stenographic work.

There's just a little bit of Scotch and a lot of Irish in Buddy and, with him, a dollar made was a dollar saved. To the amount he actually saved each week I would add fifty per cent in order to foster the thrift habit. When he would save $40.00 or $50.00 he would turn it over to me, and I would give him my note for the amount. On this I would pay him seven per cent interest.

As he grew older I paid him more wages, until, when he was fifteen years of age, he had saved $500.00, on which I paid him interest. When he was chosen to go to the Paramount school at the age of twenty, I returned to him something more than $700.00 and it was with this earned money that he paid his necessary expenses while in the Paramount Training School. So, in reality, he financed himself in the big venture.

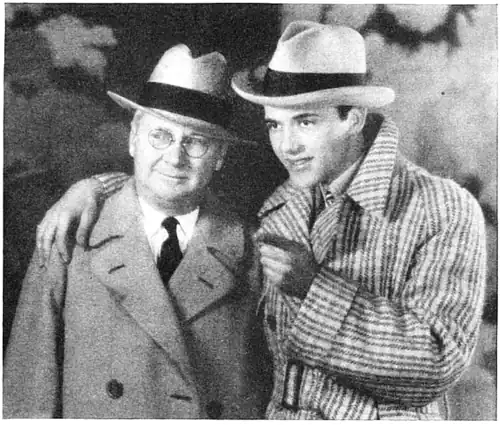

Buddy Rogers and his father, who wrote this story of his son for Photoplay. B. H. Rogers' newspaper is the oldest weekly in Kansas. Buddy started by distributing hand bills for his dad

So he did during his three years in the University of Kansas, at Lawrence, by playing drums and trombone in his college dance orchestra. His entire college expenses did not cost me a single dime—in fact, after his three years schooling, he returned to Olathe, having saved $150.00.

During the summer of 1922 Buddy took his orchestra over a Chautauqua circuit of thirteen states in the Middle West. For his services as drummer and trombonist, as well as leader of the orchestra, he received $60.00 a week, with transportation paid. Each Monday morning I received from him, to be banked in his name, all but $8.00 or $10.00, which he reserved for eats—often going without breakfast in order to send that much more home to be put in his savings account.

Nor did he stop at the best hotels on the way, as you may have surmised from the amount saved. He had a cot and slept in the Chautauqua tent. The savings of that summer, something like $700.00, he applied on the purchase of a farm near Olathe, which we now own in partnership.

It was purchased at a bargain in order to settle an estate. As it had been rented so long, it was run down, and as a result, we bought it very cheaply. We sowed the entire eighty acres to sweet clover, the greatest fertilizer known.

Now, after four years it is in wheat and it is said to be the best field in the county. The farm has doubled in value.

During the summer of 1923 Buddy and a fraternity brother, Dean Boggs, together with twenty other college youths, went to Spain as chambermaids to a shipload of 800 mules. A Spanish buyer had purchased these in Kansas for shipment to Barcelona, Spain. Each boy received $1.00 per day and expenses on the trip. They toured the country, then came back on a steamer, as steerage passengers, landing at New York, where they bought an old Ford, drove through to Olathe, arriving here with but ten cents each in their pockets. The Ford was traveling then on four rims.

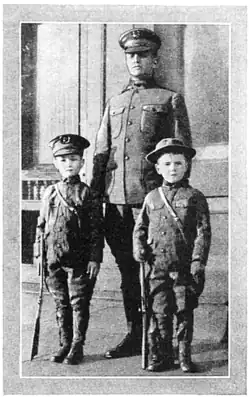

At the left you see Buddy. At the right is his chum, Robert Thorne. The military guardian is Buddy's uncle, A. G. Moll, of the U. S. Army

JUST here I want to say two things about Buddy, which to mean mean infinitely more than his immense salary or the unlimited publicity he receives. First—he has never given me a minute's anxiety in his whole life of twenty-four years; second—he has not changed in the slightest degree from the day he was five years old or ten or fifteen or twenty.

I think more of a statement of his, which you may have read, than I would think of a gift of a million dollars. That statement was made some weeks ago, when an interviewer asked Buddy what his reaction was to all this fame, wealth and the receipt of 23,000 fan letters a month. As you know, he leads all men of the movies by a wide margin. Among actresses, only Clara Bow and Billie Dove receive more. The statement is as follows:

"It may sound funny when I say it, but the truth is that the public has been so kind to me, that my ambition is to return some of that kindness by being thoughtful and considerate of everyone with whom I come in contact.

"I'd like to prove by my conduct in life that I sincerely appreciate the good fortune that has come to me."

WHEN I read this tears came to my eyes and a lump in my throat, for I knew the words came from his heart. No high-powered publicity man ever made such a human interest statement and attributed it to the person interviewed. As I write this I am affected in the same manner. I ask the readers of this article if you can conceive of a more appealing answer? Or one that would please you more if he were your boy?

Buddy's sister, Geraldine, now Mrs. John Binford, was a student at the U. of K. and Buddy often went up to see her and attend fraternity dances while he was still in high school. He learned that college boys playing in a dance orchestra often made from $12.00 to $15.00 a night at Friday and Saturday night dances. So, at the beginning of his senior year in high school, he bought and paid for, out of his own money, a full set of drums and traps, and, as there was no one to teach him in Olathe, he bought records for our phonograph, where drum music predominated, and played with the phonograph until he learned to play the drums well.

He learned the trombone in much the same manner as the drums, using a battered brass horn, which I had purchased for his younger brother.

This old trombone he played in his own orchestra, which he organized during his last two years in school.

Then he took it with him to the Paramount school, where he played on the sets and during the noon hour, greatly to the delight of everyone. This one thing gave him a great boost with the school authorities and, in reality, is probably the largest factor in his success today. Later he learned other musical instruments, until he could handle five, besides the piano. In his first all-talkie, "Close Harmony," he plays all these, besides singing.

At the age of nine, Buddy Rogers was the baritone of the Olathe Boys' Band. You will note Buddy in the second row from the top, the third from the left. Little did Olathe think then that Buddy would become a movie star

NO doubt you are familiar with the manner of his selection for the Paramount Training School, which was the direct means of his entering the movies and today being a star. In the advertising of the Paramount-Famous Lasky studio, published some days ago, his name was listed as one of their nine stars, though there are thirty-four feature players listed. And, by the way, of this forty-three, all but Buddy and two others have had stage or screen experience, according to a statement by Paramount.

I was on intimate terms with S. C. Andrews, owner of two local picture theaters. When Paramount made known that they were about to open a training school, where young people would be taught to be actors, and those who made good would be given contracts, he at once submitted Buddy's picture to the district manager, Earl Cunningham, Kansas City (one of the 35 centers throughout the United States where applications were received).

Mr. Cunningham informed Mr. Andrews that such a boy might have a chance. So I filled out the necessary blanks.

You see, Buddy knew nothing of it at all. He was busy studying journalism at the U. of K. in order to be able to come back and help me on the paper.

I saw that the instructions were to get two recommendations. Then and there I conceived the thing that put Buddy in pictures, though of course he could not have gotten in if he had not filmed well. I said to myself, "I'll not stop with two stereotyped recommendations, such as are many times written—'I have known so and so a long time. He is O.K. Please do what you can for him and oblige me.'"

I went first to Mr. Andrews and asked him to give a general account of Buddy and what he considered he might bring to the screen, if selected.

Then to eleven others in Olathe, in entirely different lines of business, all of whom had known Buddy since he was born, and had also known his mother and me for years, as we were both born in Olathe. I asked them to write at some length of their views on Buddy, in his associations with them in their particular lines.

So these letters were written by his two bankers, F. R. Ogg and S. B. Haskin; his minister, the Rev. Mr. Brown, of the First Methodist church; Judge G. A. Roberds, of the District Court; his Sunday school teacher; Superintendent E. X. Hill of the Olathe High School; F. D. Hedrick, county attorney; the Honorable C. B. Little, Congressman from the 2nd District of Kansas, who lives near my home; State Senator John R. Thorne, who lives near us; Dr. C. W. Jones, our family physician, who piloted the stork to our house with Buddy; F. M. Lorimer, President of the Chamber of Commerce; and John W. Breyfogle, Olathe editor.

YOU can imagine that Buddy was pretty thoroughly "covered" by the time these twelve letters were written, all from a different angle.

Buddy had just recently had some pictures taken, one of them mounted on a large folder, somewhat larger than the letterheads on which his recommendations were written. I stapled his recommendations to this picture, which we thought very good. Then I put a nice cover sheet over all, on which I printed, "Character Sketch and Characteristics of Buddy Rogers by Twelve Olathe Men."

I did all this work myself at the office at night, as I didn't want to have to explain to my force what I was doing. I feared that Buddy might fail to land the place.

And just here I want to say that, after Buddy had been in the school some two or three months, Mr. Lasky. himself, called him into the office one day and said, "Buddy, do you know how you happened to be selected to enter the school?" Buddy answered that he did not, but that he had often wondered to what to attribute his good fortune.

Then Mr. Lasky said, "It was not on account of your good looks. You are good looking enough, for that matter, but that wasn't the reason. It was on account of those marvelous recommendations. Never have I read such good ones, and you are living up to all that was said about you. We believe such a boy as you will be a power for good in this school and in pictures."

But, do you know how nearly Buddy missed being in pictures today? One of his instructors, Mr. Currie, told me the next summer after the school had opened in August, that they had seen nothing to indicate that Buddy had any talent at all for pictures. He thought he was a nice boy—but that was all.

That, at the end of the first month, they were on the point of sending him home (a right they reserved), when all at once—it seemed over-night to them—his latent talent showed up to an amazing degree. They realized that he had simply been assimilating what he had learned in the first four weeks. From that moment, Mr. Currie said, Buddy was the outstanding member of the class.

OF the 40,000 applicants for this school, only twenty were chosen, and four were sent home at the end of the first month. This left eight boys and eight girls in the school and, of this number, only five are now in pictures, and only three with Paramount—Thelma Todd, Jack Luden and Buddy.

Buddy was by far the youngest of the boys, and the only one of the twenty who had had no stage or movie experience. His was limited to good parts—usually the lead—in grade school and high school entertainments and plays.

In his senior year he was given the lead in a class play, "Clarence," the part taken by the late Wallie Reed in the movie, "Clarence," and many said his work in that was almost equal to Wallie's.

No one will ever know the heartaches that were Buddy's during the first few weeks of the six months' term of the Paramount school. He was a shy, quiet, country boy, whose experience was limited to a small town, save for his brief years at the university. As all the others in the school, with the exception of two, were from New York or Hollywood and had seen a great deal of the world, they knew what it was all about. Buddy didn't.

He was made the butt of many ill-timed jokes and often referred to as the country kid or "Merton of the Movies," and I believe this had much to do with his appearing rather slow to learn.

He knew it and wrote very discouraging letters to us, saying, "I guess I'm just too dumb to learn. I guess I'll be sent home and I'll have to go to work for Dad." At another time he mentioned that someone had said that he was about as humorous as Lincoln looked.

It was heart-breaking to us knowing how he was trying so hard for our sakes to make good. He never had failed us in a single thing, he knew our disposition and feeling toward him, and that we believed he could do anything. That's why he felt he simply could not fail us.

When particularly discouraging letters would come, we would either call him up, send a night letter of fifty words or a special delivery letter to cheer him.

Do you wonder what advice I gave him when we drove to Kansas City, Missouri, twenty-five miles from Olathe, to put him on the train for New York to attend the training school? It was just the same as I gave him when he started to Europe on the mule boat—and just exactly the same as I gave him when he left home for the university.

You're wondering how each could have been the same. The answer: None! Not a word of advice, or don'ts. I was the last one to kiss him goodbye and, with choking voice, said only, "Buddy, I want you to feel that we know you'll always do the right thing." And never once has he failed us.

When he went to Spain with the mules, his grandfather Rogers, now deceased, told him, "Buddy, I have only this to say. There's always just two things to watch—your morals and your health. Your morals are already fixed. Watch your health."

How could any boy get away from such faith and trust as this—even if he wanted to. No doubt there are many, many boys in the world as good as Buddy—but there are none better. And Hollywood has not changed him one iota, except that it has made him more thoughtful, more considerate.

I believe the biggest day of my life was when the Junior Stars (the Paramount class) came to Kansas City to appear in person in the class picture, "Fascinating Youth," at the Newman Theater. Buddy had the lead. The others of the class had been traveling with the picture, making personal appearances, but Buddy had been sent on to Hollywood to work, for he was the first one assigned to a picture, after the school had closed. However, he was sent back to Kansas City to appear with the class.

THE whole town turned out, as this was Buddy's first visit home. The band played, flags were out, signs were up everywhere and at dinner several hundred came to the hotel. Different organizations read resolutions, complimentary to Buddy. He was hoisted to the shoulders of business men and high school boys, carried outside and presented with a ring which carried his initial, B.

Then he was placed in a donkey cart all covered with banners, such as "Welcome Home, Buddy." There was a parade around the square.

You can well imagine how I felt. I had a similar feeling, no later than last week, when Buddy's first all-talkie, "Close Harmony," had its world premiere in Kansas City at a midnight preview.

I was proud to have been invited by the manager to press the button which started the picture, as it was Buddy's first all-talkie. It also was my first. I had never heard one before.

I might add, here, that the midnight showing broke any previous record for midnight previews, there. With the single exception of "The Singing Fool," it easily broke any other record for the week—and by several thousand dollars. Probably one reason for this is that Kansas City, being so close to Olathe, "claims" him, as, of course, Olathe properly does. Moreover, it was on the Newman stage that his first screen test was taken, more than three years ago.

When his first picture, "Fascinating Youth," showed in Olathe for three nights, the crowds were so large that Mr. Andrews made enough money to buy a new car, which he called his Buddy Car. Recently he had another of his pictures and, since two years have elapsed, his car needed to be traded in and he made enough money to buy another Buddy Car.

You may be sure that I have a funny feeling whenever the local picture owner brings in the mats and the press sheet for one of Buddy's pictures. My instructions always are for his pictures to get a "great big mat" for that week, the ad is complimentary, no matter what the size and, in addition, I run a half column of reading matter on the front page, being careful to put as a lead an article that is copied from the company's press sheet.

IN such cases as this I am a combination of editor and father—but the preponderance of "father" is easily seen. Pictures for the paper are cast with hot metal from mats and often the face of the metal must be scraped down to print clearly and avoid a blur. We had been doing this with a sharp chisel and hammer, but it often would spoil the picture. So, when Buddy entered the school, my foreman said, "Will you buy us an electric router when we get Buddy's first advertisement?" I answered that I would—and, when it came in about a year, I was held to my promise to buy one and at a cost of $300.00. So Buddy has improved the looks of the Mirror'.

It seems that Buddy has always wanted to be a musician. Even as a baby and little boy he would get a drum, horn or fife for Christmas. Once, in Kansas City, we saw a vaudeville act where one man played eight or ten band instruments and, from that day to this he has always wanted to be a one-man orchestra.

In "Close Harmony" he leads his jazz band, plays all these instruments, sings and then turns a hand spring, standing on top of the piano, to the floor. I have heard from a half dozen towns playing "Close Harmony" and in each instance the box office record has gone tumbling.

Buddy Rogers lives quietly in Hollywood. Despite his stellar salary, he still resides with his pal, Dean Boggs, paying $16 a week for his board, room, garage and a kennel for his police dog

For several months Buddy worked in "Wings," completing it just two years ago, and then he was drawing a salary on his contract of but $75.00 per week. Now he is working under a new contract and his former salary is simply pin money now. Since making "Wings" he has worked in "My Best Giri" with Mary Pickford, "Abie's Irish Rose," "Varsity," "Someone to Love," "Close Harmony" and others and is now making "Magnolia."

Buddy is diversifying his investments. real estate, stocks and bonds, building and loan, and he still continues to live with Dean Boggs at his home in Hollywood, paying $16.00 per week for his board, room, garage and kennel for his German police dog, Baron. He refers to Mrs. Boggs, Dean's mother, always, as "My California Mother." Both boys are members of the Phi Psi fraternity.

'Lest you should get the impression that all Buddy's spare money goes into investments of some kind, I want to say that before his present new contract (just signed) when his salary was not large—as movie salaries go—he sent a great deal of money home to his family. Paid the expenses and purchased complete wardrobes for his mother and sister on their frequent trips to New York and Hollywood to visit him.

I well remember his first bonus for good work on his first starring picture, "Varsity." He wired all the money home except $200.00—and almost that much on subsequent bonuses.

The first Christmas following his entering pictures we found at our door, on getting up late Christmas morning, a brand new automobile with only this to identify it—

"To my family

Merry Christmas and Love

Buddy."

Just a year ago, when coming through Olathe, going to location at Princeton University, he found his kid brother had done so well in his junior year at Olathe high school, both in books and athletics, that he purchased a sport coupe for him.

If anything, he has been too generous with us in money matters. But he says that is his greatest enjoyment—that, and having some member of his family with him just as much as possible.