Pet Birds of Bengal/The Bhimrāj (Racket-tailed Drongo)

THE BHIMRĀJ

(DISSEMURUS PARADISEUS)

It is strange that some of the forest birds, properly so-called, living far away from the haunts of man, are our dearest and most loving pets. The Shamā is one of this class, the Bhimrāj or the Racket-tailed Drongo is another. The perfect sang-froid with which both these birds accept the fellowship of man is remarkable. Both seem to regard the love and confidence of their keeper as sufficient compensation for their loss of liberty, and both become most intimate with their master. To win the confidence of naturally shy birds, no little tact is required. Great credit is therefore due to the Indian bird-fancier who accomplishes this feat. He is unacquainted with the modern process of bird-keeping, yet he seldom fails in his attempts to bring up the most delicate birds, the rearing of which baffles the skill of even an up-to-date aviculturist. His lack of scientific knowledge is counter-balanced by a a loving heart, patient care, and the wisdom of following the traditional methods instead of hazarding innovations. He, at times, works wonders by his primitive methods. His protege is often as tame as a cat or a dog.

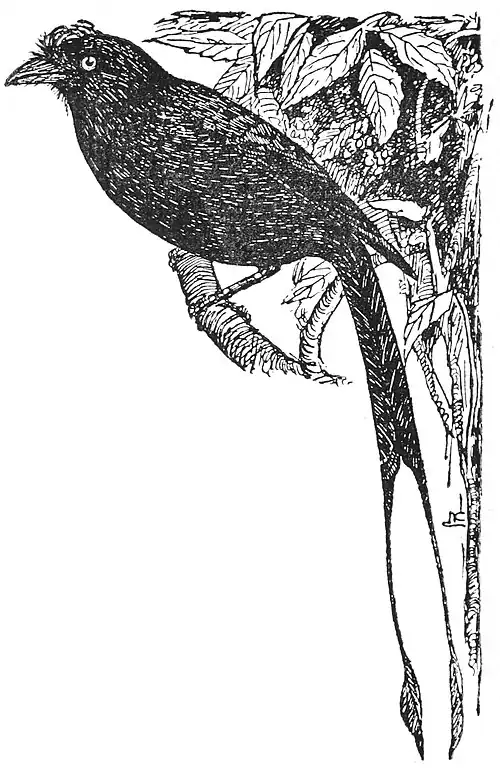

The Bhimrāj is quick in reciprocating the caresses bestowed on it by its master. Under the latter's guidance, it grows to be a most alluring pet. Nature has endowed it with a boldness of spirit, a sense of aggressive self-defence, a charming song and an unlimited power of mimicry,—traits which become prominent even in captivity. The peculiarities of its body are found at the head and the tail. The head is ornamented with a raised and somewhat incurved crest, while the posterior appendage has two of its feathers unusually exaggerated to a length of over a feet and a half, the shaft being bare for a few inches and ending in a racket-shaped expansion. Its dense black colour with dark steel-blue sheen makes it a very handsome bird.

A bird of many qualities, can scarcely fail to attract notice. The Bhimrāj's fame has crossed the seas, and foreign writers have spoken of it in superlative terms.

To the scientist, the Bhimrāj is known as Dissemurus paradiseus. On the mainland of India, two types of the Bhimrāj are seen,—the continental and the peninsular, the latter having the crest and tail shorter. Scientists had a controversy over its division into more species than one. But Oates, in the Fauna of British India, rather arbitrarily included both the types into one single species under the genus Dissemurus. Mr. Stuart-Baker, who is at present editing the second edition of the Avi-fauna of British India, in his Hand-list of Indian Birds, published recently in the Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, has split up the genus into seven species. Under the trinomial system of nomenclature adopted by him, the bird known as Bhimrāj in Bengal has received the appellation Dissemurus paradiseus grandis.

Its range may roughly be said to extend over all the forest-regions of India, Burma, and Ceylon. All the birds have a crest, and two racket-like tail-feathers,Distribution but both are shorter in the South-Indian and Tenasserim specimens.

The Bhimrāj is found in lower Bengal and the Sunderbans, in Central India, Orissa, Chota Nagpur, and Assam. From Khandesh all along the Western Ghats up to Travancore it is numerous, but the birds of the Deccan are smaller than those of Northern India. Along the Eastern sides of the Peninsula, however, the Bhimrāj is comparatively rare. Ceylon is inhabited by the Peninsular form of the bird. From India its range extends eastwards to Burma, and through Tenasserim to Siam and Malaya, but here again, the continental type is replaced by the Peninsular.

Thick and luxuriant forests or jungles, jungle-clad river-sides or low hills which are full of tall trees are the favourite resorts of this bird. In certain localities,Field Notes for example in Burma, it does not absolutely avoid the neighbourhood of man, straying sometimes into the outskirts of villages on the borders of a jungle. In the outlying groves of the villages or in the trees bordering an unfrequented tank, it may be seen chasing an unfortunate Woodpecker which had the audacity to trespass into its domain. The Bhimrāj has a special dislike for the Woodpeckers. It is not an unusual sight to see these short-tailed, many-coloured birds dashing, as if for very life, with a long-tailed swarthy Bhimrāj in hot pursuit. Even the hen Drongo is a perfect amazon and heartily joins in the chase. This Drongo is a highway-man of the bird-world and a veritable swash-buckler. It seldom allows its neighbours a peaceful life. As soon as it notices a smaller bird from its lofty perch, it charges down to secure perhaps the insect which the latter has in its beak. Robbery is not always the purpose in its pursuit of other birds. It often would give chase in sheer mischief, only to enjoy the discomfiture of the frightened birds. For it has been noticed that though the Bhimrāj sweeps down on other birds, it does not always follow them upwards. Its boldness increases during the nesting season when, with its mate, it attacks and drives off, from the neighbourhood of its nest, preying birds like Harriers or Eagles. Its anxiety for its brood would even lead it to attack quadrupeds. Major Bingham, when out for an excursion in a jungle in Burma, passed close to a tree in which a pair of Racket-tailed Drongoes were nesting. Says he, "I was wading across the mouth of the Theedoquee, when my attention was attracted by seeing a pair of above birds dart from a small tree and sweep down at my dog, not actually striking him, but nearly doing so."

Its predatory nature, however, does not make it an unsociable bird with its own kith and kin. The Drongoes as a class are not over-fond of company. It is otherwise with the Bhimrāj. Generally, it goes about in pairs. But it is not unusual to see parties of four or more together. These birds seem to care little about territorial possessions and never restrict their movements to any limited area. Flying from tree to tree in search of food, they cover daily a wide range of ground. Ocassionally, one sweeps down and picks up an insect on the wing swallowing it as it mounts up again. Sometimes the prey is carried to a branch to be eaten. It seldom alights on the ground for its prey. It is an excellent catch and is very clever at taking flies on the move. Frequently, it feeds like the common king-crows  from a fixed position on a branch whence it whips up insects or makes swoops at those flying past. Its flight is usually undulating, when proceeding any distance, but when making short sallies after insects, they shoot up rocket-like. At such times, one cannot help admiring the ease with which it uses its long tail which does not seem to obstruct its movements in the least. A writer remarks, "No high-born dame ever carried her

from a fixed position on a branch whence it whips up insects or makes swoops at those flying past. Its flight is usually undulating, when proceeding any distance, but when making short sallies after insects, they shoot up rocket-like. At such times, one cannot help admiring the ease with which it uses its long tail which does not seem to obstruct its movements in the least. A writer remarks, "No high-born dame ever carried her

court-train with greater grace". The food of the Bhimrāj consists of large bees and wasps, locusts and dragon-flies. Lizards and rats also occasionally form its menu. It is always restless, flying from branch to branch, jerking up the tail and making frequent plunges for insects from its elevated position. Between these movements, it is repeatedly calling to its mate who is engaged in similar activities in a tree close by.

court-train with greater grace". The food of the Bhimrāj consists of large bees and wasps, locusts and dragon-flies. Lizards and rats also occasionally form its menu. It is always restless, flying from branch to branch, jerking up the tail and making frequent plunges for insects from its elevated position. Between these movements, it is repeatedly calling to its mate who is engaged in similar activities in a tree close by.

Its notes deserve mention, though it is difficult to hit off an exact description in a few words; for it can produce an immense variety of sounds from bass to soprano, some of which are beautifully clear and melodious. Oates gives it the premier place among the song-birds of India. Its general note is a deep sonorous cry like tse-rung, tse-rung, tse-rung. Jerdon describes it as "consisting of two parts, the first, a sort of harsh chuckle ending in a peculiar metallic sound, something like the creaking of a heavy wheel." It indulges in these metallic calls early in the mornings and evenings. A favourite pastime with the Bhimrāj is mocking all sorts of birds around it. It has been heard to imitate perfectly such different birds as the Malabar Black Woodpecker, Malabar Grey Hornbill, Cuculus micropterus and Eudynamis honorata.

This stalwart bird breeds and rears up its young between the months of April and June. It always selects big trees for nesting, and the nest isNests and Eggs built at inaccessible places. The extreme tip of a branch, on the top of a tree about 20 to 25 feet from the ground, is the the place generally chosen. Here in a fork, the cup-shaped nest is clumsily built up of twigs and creepers, with an inner lining of dry grass. The nest hangs like a cradle below the fork to which it is strongly attached. Three is the usual number of a clutch of eggs, which are long ovals, pointed towards the small end and without any gloss. These eggs are seldom uniform in colour, varying from white to a rich pink and spangled with markings of red, purple, reddish brown or inky grey. These marks are in some cases large blotches, while in others mere specks sprinkled over the surface thickly in some, thinly in others, but as a rule, the largest blotches are about the large end.

A large cage, at least three feet square, is the most suitable dwelling for the Bhimrāj. In an aviary, it would no doubt thrive splendidly, but if itCage-life be a mixed one, this ruffian would make the place hot for the less sturdy inmates. With pigeons and chukor partridges, it will readily form an entente cordiale; but if other species of Drongoes or smaller birds like Magpie-robins be there, bloody strife is sure to occur. Therefore, this Knight-Templar should be housed with such birds as can hold their own against it.

Though its behaviour towards its kindred is typically hunnish, it is a marvel of good conduct with its keeper. With him, the bird is perfectly sociable and its knowing and intelligent ways afford him a great deal of amusement. It loves to be noticed and fondled and is never so happy as when carried about on the finger and petted. Under the fostering and almost paternal care of its keeper, its naturally robust disposition gets full play to develop all its good points. A life of captivity does not at all dull its talents. Its power of mimicry not infrequently enables it to indulge in fun at the expense of other birds. A Bhimrāj was known to frighten a Shama by mewing like a cat. As a ventriloquist, it gives the palm to no Indian bird. It can render with perfect fidelity, and perhaps with added charm, not only the songs of other birds within hearing, but various other sounds. It can yelp like a puppy, mew like a cat, bleat like a lamb, and imitate the voices of poultry.

The Indian bird-keeper does not find much difficulty in steadying the Bhimrāj. The ordinary satoo mixture with a constant supply of insects, maggots, and a few cockroaches keeps it fit. In the Calcutta Zoo Gardens, it was noticed to hawk upon rats and lizards straying into its aviary. It will never come down to the ground for picking up its food. So its food-cups must be tied high up near its perch. Occasionally, but sparingly, very finely minced meat may be given. Too much of this food may bring on indigestion. It is not a frugivorous bird, though it has been, in captivity, noticed to take fruit. It loves bathing and should be provided with a fresh-water bath. It does not ail much in our climate except for bad moult. The only treatment for this seems to be good food and cleanliness.

In England, successful attempts have been made to acclimatize the bird. There it requires a good deal of careful treatment. It cannot stand cold at all, and so, except in summer, artificial heat is necessary to keep it warm. Reginald Phillips prescribed for it the following diet—"cockroaches, earwigs, chafers, wood-lice, flies, beetles, grasshoppers, grubs, almost any living creature. Naked nestling canaries and sparrows would form a valuable change, also baby mice cut up would help. Mealworms are indigestible. A grape or two may be placed within the reach of the bird as medicine."

The Bhimrāj is the finest and the most sightly bird of the Drongo family. Its whole body including the bill, feet, and claws, is clothed in sable,Coloration but the colour is not the funeral black of Il penseroso. Except the throat, lower abdomen and vent, the rest of the body is glossed with blue, which shows brilliantly in sunshine. Its forehead is tufted with feathers of varying length,—the birds of Northern  India having the tuft quite two inches long, while those of Southern India and Burma have one or even less than one inch. The characteristic feature of the bird is the great elongation of its outer tail-feathers like those of the Bird of Paradise. The inner webs of these two tail-feathers gradually thin off and the shaft is bare for some length. The terminal portion is webbed and twisted upwards. The web on the inner side of the shaft is very narrow. The bill is large, strong, and compressed towards the tip. The culmen is well-curved, hooked, and distinctly notched. Iris is red in the adult and brown in the young. The crest of the young birds just after leaving the nest (in July) is not long enough to curve backwards, the long tail-shafts are not denuded in the middle as in adult birds, and the wings have a green tinge.

India having the tuft quite two inches long, while those of Southern India and Burma have one or even less than one inch. The characteristic feature of the bird is the great elongation of its outer tail-feathers like those of the Bird of Paradise. The inner webs of these two tail-feathers gradually thin off and the shaft is bare for some length. The terminal portion is webbed and twisted upwards. The web on the inner side of the shaft is very narrow. The bill is large, strong, and compressed towards the tip. The culmen is well-curved, hooked, and distinctly notched. Iris is red in the adult and brown in the young. The crest of the young birds just after leaving the nest (in July) is not long enough to curve backwards, the long tail-shafts are not denuded in the middle as in adult birds, and the wings have a green tinge.

From tip to tip, the Northern bird is about 26 inches in length. This dimension is due to the long tail-shafts which alone sometimes extend up to twenty inches. The middle tail-feathers are not more than five or six inches, and the body proper does not exceed a foot.

In Vol. XIII of the Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, Finn records a case of albinism in the present species. In the specimen, the upper and lower wing-coverts except the primary coverts, inner scapulars, axillaries, upper tail-coverts and the lower plumage from breast downwards were white, edged with black; the rump and the under tail-coverts were entirely white. There were also some white streaks on the lower breast and a shading of white on the inner webs of the tail-feathers and innermost secondaries, and on the outer webs of the outer secondaries. The bird was obtained from a bird-dealer of Calcutta. Finn was not inclined to accept it as an aberration. He writes, "Taking into consideration the extreme rarity of symmetrical albinism (except in the case of albinoid or pallid varieties) and the fact that the appearance of this specimen is not suggestive of ordinary albinism, but rather of specific difference, I venture to characterize it as new, and name it Dissemurus alcocki. "

Birds with black plumage are not infrequently prone to albinism. But a symmetrically albino specimen is a case of extreme rarity. Finn says that he was informed of three similar other birds having passed through his bird-dealer's hands, all of which were procured from Sigowli in the Gorakhpur district. I am inclined, however, to put little trust in the testimony of his bird-dealer, and in the absence of sufficient data, I cannot but regard Finn's specimen as an aberration. The occurrence of a couple or two of birds with symmetrically white parts (even if we believe the bird-dealer) is not sufficient, in my judgement, to warrant the haste, as Finn has shown, for species-making.