Page:The Strand Magazine (Volume 7).djvu/533

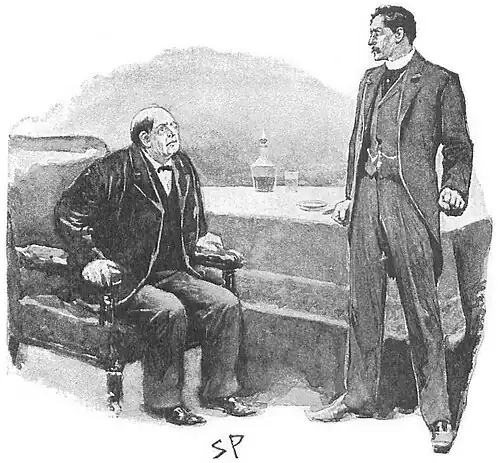

"I set back my chair and stood erect before him. This grovelling wretch, forcing the words through his dry lips, was the thief who had made another of my father and had brought to miserable ends the lives

"I stood erect before him." of both my parents. Everything was clear. The creature went in fear of me, never imagining that I did not know him, and sought to buy me off; to buy me from the remembrance of my dead mother's broken heart for £500—£500 that he had made my father steal for him. I said not a word. But the memory of all my mother's bitter years, and a savage sense of this crowning insult to myself, took a hold upon me, and I was a tiger. Even then, I verily believe that one word of repentance, one tone of honest remorse, would have saved him. But he drooped his eyes, snuffled excuses, and stammered of 'unworthy suspicions' and 'no ill-will.' I let him stammer. Presently he looked up and saw my face; and fell back in his chair, sick with terror. I snatched the pistol from the mantelpiece, and, thrusting it in his face, shot him where he sat.

"My subsequent coolness and quietness surprise me now. I took my hat and stepped toward the door. But there were voices on the stairs. The door was locked on the inside, and I left it so. I went back and quietly opened a window. Below was a clear drop into darkness, and above was plain wall; but away to one side, where the slope of the gable sprang from the roof, an iron gutter ended, supported by a strong bracket. It was the only way. I got upon the sill and carefully shut the window behind me, for people were already knocking at the lobby door. From the end of the sill, holding on by the reveal of the window with one hand, leaning and stretching my utmost, I caught the gutter, swung myself clear, and scrambled on the roof. I climbed over many roofs before I found, in an adjoining street, a ladder lashed perpendicularly against the front of a house in course of repair. This, to me, was an easy opportunity of descent, notwithstanding the boards fastened over the face of the ladder, and I availed myself of it.

"I have taken some time and trouble in order that you (so far as I am aware the only human being beside myself who knows me to be the author of Foggatt's death) shall have at least the means of appraising my crime at its just value of culpability. How much you already know of what I have told you I cannot guess. I am wrong, hardened and flagitious, I make no doubt, but I speak of the facts as they are. You see the thing, of course, from your own point of view—I from mine. And I remember my mother.

"Trusting that you will forgive the odd freak of a man—a criminal, let us say—who makes a confidant of the man set to hunt him down, I beg leave to be, Sir, your obedient servant,

"Sidney Mason."

I read the singular document through and handed it back to Hewitt.

"How does it strike you?" Hewitt asked.