Page:The Strand Magazine (Volume 6).djvu/47

received a letter from his son, a Captain in a crack French regiment. Ce cher Alphonse had been playing baccarat, it seemed, and to meet his losses the Count was compelled to withdraw for the moment the whole of his balance in the hands of the bank, though it would be replaced a few days later by remittances from other sources.

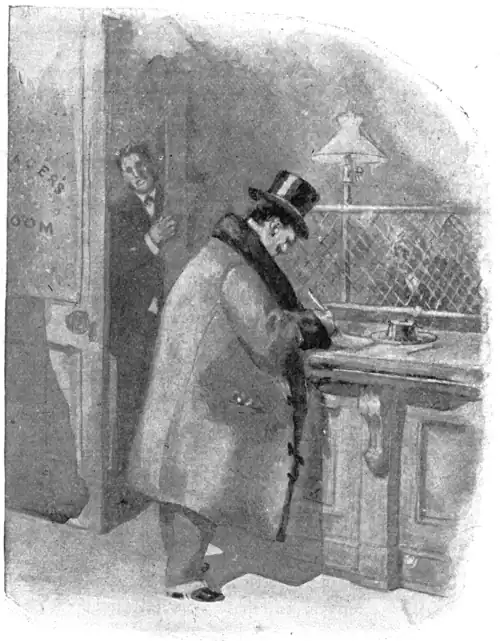

"He drew a cheque for the amount."

I instructed a clerk to see how the Count's account stood, and the balance having been ascertained, he drew a cheque for the amount and departed with the money. "The plot thickens," said Macpherson, when I told him of the visit. "The grand coup is in all probability for to-night."

We watched accordingly. So soon as we had dined, we took up our position in my office. Our first proceeding was to cover up the bull's-eyes in the floor, that no light might shine through to the vault beneath. Macpherson next muffled the clapper of the electric alarm, so that it should give no sound beyond a faint tapping, sufficient to call our own attention, but not loud enough to be heard beyond the room in which we were. We wore felt slippers, that our footsteps might be noiseless. I had brewed a supply of strong coffee, to help to keep us wakeful, and on the table lay a couple of revolvers, and some lengths of sash-line wherewith to bind our expected captives. O'Grady was told to hold himself in readiness to come down to us instantly on receiving an agreed signal.

These preparations made, we sat down to beguile our vigil with a game of chess. At ordinary times we were very equally matched, but on this occasion Macpherson found me an easy victim. I could not keep my thoughts from wandering to the possible issues of the coming struggle. If all went well, I had but little to gain; whereas if—(an awful "if" that)—Macpherson's plan broke down, and the attempt at robbery succeeded, my career as a bank manager would be utterly blasted. At this moment I must own I heartily regretted that I had allowed myself to be drawn into so Quixotic an enterprise, when I might have saved myself all anxiety by placing the matter in the hands of the proper guardians of the peace, or simply reporting it to the directors.

Macpherson, on the contrary, appeared to be troubled by no misgivings, and played even better than usual.

"Fail!" he said, when I suggested the possibility of such an event—"we can't fail any more than I can fail to win this game, which I undertake to do in four moves. Check!" I made the best fight I could, but in four moves I was checkmated.

I was nettled at my defeat, and determined that he should not again win so easy a victory. With a strong effort of will, I concentrated my whole attention on the game, and thenceforth played as coolly as though the hidden enemy were a hundred miles away. We played on with varying fortune till about eleven, when the faint