Page:The Strand Magazine (Volume 6).djvu/37

my method of patting him to be in many respects the best. When I see Coolie against the bars and looking amiable (for Coolie), and I feel disposed to pat him, I call North, and authorize him to pat Coolie on my behalf. In this way I have become quite friendly with Coolie, who is as affable under my pats as if I were his keeper. I shall always pat Coolie like this; I am able to devote more attention to the general superintendence of the proceedings when I have an assistant to attend to the manual detail. Sometimes Sutton helps me pat the lions in the same way. It requires a little nerve, of course, but I am always perfectly cool.

Charlie.

Good wolf or bad Collie?

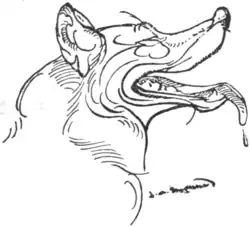

Bob, the Eskimo dog, lives in the next cage to Coolie, and in the next cage still there are a pair of prairie wolves, whose improvement on the common wolf lies only in externals. To look at, they seem a kind of collie, but with a finer model of head than any collie-breeder can produce. Except in appearance, they are far back in the blackest ages of wolfdom. One of them—Charlie—has an offensive habit of sitting up on the coping-pier from which the cage division-bars spring, because that is regarded as a sort of feat of gymnastics, impossible to the other wolves, since they are too big. If you particularly want him to perform, for your amusement, he won't do this trick, small as it is; but when you are not looking he persists in it, by way of annoying the neighbours who can't perform it. Perhaps, after all, the Dog in the Manger wasn't a dog at all, but a prairie wolf. The man who called him a dog didn't examine him closely enough; few people stay long to examine a loose wolf. Like a dog as the prairie wolf is—and he tries his utmost to maintain this respectable appearance—his drooped tail, his snarling mouth, and his small eyes, expose the pretence. He is attempting his promotion in the wrong way—merely by imitating the uniform of the superior rank.

Good old dog!

Eh!

There can be no reasonable doubt that the wolf wants to be a dog if he can. He quite understands his rascally inferiority, but will never give up his social ambition, especially when so many visitors encourage his vanity, time after time, by mistaking him for a dog. There are times when such a mistake is natural—almost pardonable. On a hot day, for instance, a wolf, to cool his mouth, will muster up a most commodious smile—present an open countenance, in fact—strikingly like that of an amiable retriever out for a run. But the wolf is too sad a