Page:The Strand Magazine (Volume 5).djvu/579

The two fellow-workers on Punch—Mr. Burnand and Mr. Furniss—run pretty level in their ideas. A happy thought is often suggested to both of them through reading the same paragraph in a newspaper, and they cross in the post. We spoke of Punch's Grand Old Man—John Tenniel—of clever E. J. Milliken, whose really wonderful work is yet but little known. Mr. Milliken wrote "Childe Chappie"—and is "'Arry." Of Linley Sambourne, whom Mr. Furniss once saw walking down Bond Street, and had the strange intuition that he was the artist, connecting his work, and walk, and bearing together. He had never seen or spoken to him before. Charles Keene's name was mentioned. It was always the hardest matter to get Keene to make a speech. He far preferred the famous stump of a pipe to spouting. Mr. Furniss hurt Keene's feelings once with the happiest and kindest of compliments. It was at a little dinner party, and Mr. Furniss linked Keene's name with that of Robert Hunter—who did so much to provide open spaces for the people. He referred to Keene as "the greatest provider of open spaces!" Keene said he was never so grossly insulted—he never forgave Mr. Furniss. He failed to see the truly charming inference to be drawn from this remark.

We went into the drawing-room, and together ran through the pages of a huge volume. It contained the facsimiles of the pictures which comprised one of Mr. Furniss's biggest hits—what was in reality an attack on the Royal Academy. His "Artistic Joke"—a sub-title given to this exhibition by the Times in a long preliminary notice—created a sensation six years ago. He attacked the Royal Academy in a good-natured way, because he was not himself a member of that influential body. But there was a more solid and serious reason. "I saw how cruel they were to younger men," he said; "the long odds against a painter getting his work exhibited, the indiscriminate selection of canvases."

This really great effort on the part of Mr. Furniss—this idea to caricature the style of the eminent artists of the day—kept him at work for more than two years. There were eighty-seven canvases in all. His friends came and went, but they saw nothing of the huge canvases hidden away in his studio. He worked at such a rate that he became nervous of himself. He would go to bed at night. He would wake to find himself cutting the style of an R.A. to pieces in his studio at early morn—in a state of semi-somnambulism. He fired his "Artistic Joke" off, the shot went home, and the effect was a startler for many people and in many places. It advanced Mr. Furniss in the world of art in a way he never expected, and did not a little for those he sought to benefit. One of these "jokes"—and a very dramatic one—is reproduced in these pages.

"The assassinated scarecrow, sor!"

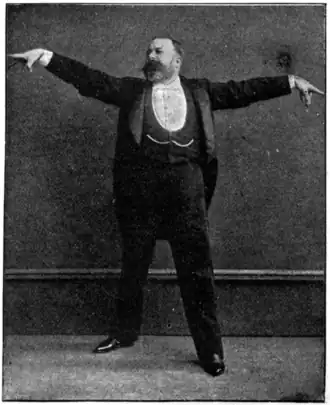

The hour or two passed in the little drawing-room after dinner was delightful. We had his unique platform entertainment. Mr. Furniss was induced by the Birmingham and Midland Institute to appear on the platform as a lecturer. This was followed by his lecturing for two seasons all over the country, but finding that the Institutes made huge profits out of his efforts, and that his anecdotes and mimicry were the parts most relished, he abandoned the rôle of lecturer for that of entertainer with "The Humours of Parliament." As soon as he had crushed the idea that it was a lecture, people flocked to hear his anecdotes and to watch his acting, the result of his first short tour resulting in a clear profit of over £2,000.