Page:The Strand Magazine (Volume 42).djvu/303

dinner. I told myself over and over again as I performed my simple toilette that I would make Miss Goodridge eat her words before she had done, though at that moment I had not the faintest notion how I was going to do it.

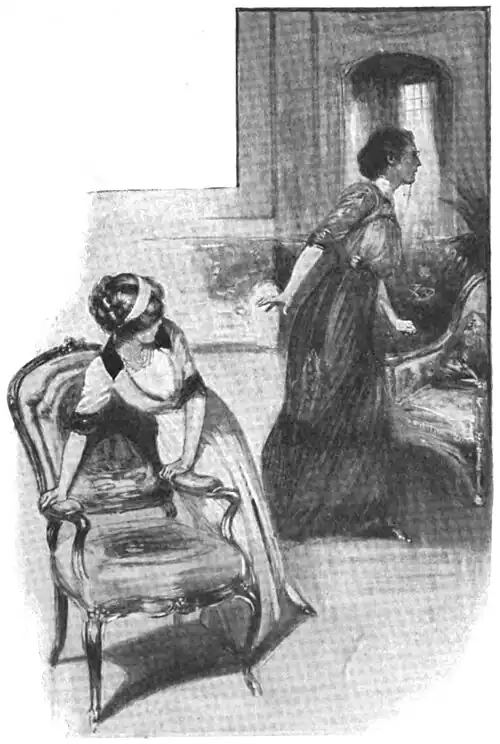

"Get out of my way! Don't you ever dare to speak to me again."

That was a horrid dinner—not from the culinary, but from my point of view. If the dinner was horrid, in the lounge afterwards it was worse. Miss Sterndale actually had the audacity to come up to me and pretend to play the part of sympathetic friend.

"You seem to be all alone," she began. I was all alone; I had never thought that anyone could feel so utterly alone as I did in that crowded lounge. "Miss Lee, why do you look at me like that?" I was looking at her as if I wished her to understand that I was looking into her very soul—if she had one. Her smiling serenity of countenance was incredible to me, knowing what I knew. "Have you had bad news from home, or from Mr. and Mrs. Travers, or are you unhappy because Mrs. Hawthorne has gone? You seem so different. What has been the matter with you the whole of to-day?"

I was on the point of giving an explanation which I think might have startled her when I happened to glance across the room. At a table near the open window, Mr. Sterndale was sitting with Miss Goodridge. They were having coffee. Although Miss Goodridge was sitting sideways, she continually turned her head to watch me. Mr. Sterndale was sitting directly facing me. He had a cigarette in one hand, and every now and then he sipped his coffee, but most of the time he talked. But, although I could not even hear the sound of his voice, I saw what he said as distinctly as if he had been shouting in my ear. It was the sentence he was uttering which caused me to defer the explanation which I had it in my mind to give to his sister.

"Of course, the girl's a thief—I'm afraid that goes without saying." It was that sentence which was issuing from his lips at the moment when I chanced to glance in his direction which caused the explanation I had been about to make to his sister to be deferred.

Miss Goodridge had her coffee-cup up to her mouth, so I could not see what she said; but if I had been put to it I might have made a very shrewd guess by the reply he made. He took his cigarette from his lips, blew out a thin column of smoke, leaned back in his chair—and all the time he was looking smilingly at me with what he meant me to think were the eyes of a friend.

"It's all very well for you to talk. I may have had my suspicions, but it is only within