Page:Punch Vol 148.djvu/610

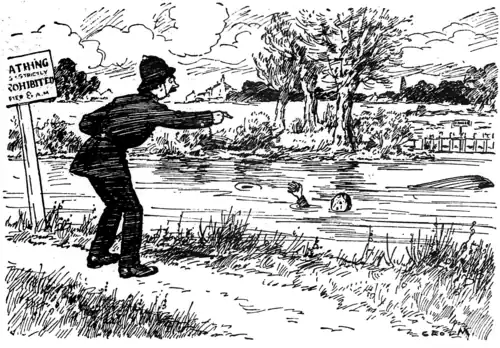

Rural Constable. "Now then, come out o' that. Bathing's not allowed 'ere after eight a.m.!"

The Face in the Water. "Excuse me, Sergeant, I'm not bathing; I'm only drowning."

OUR BOOKING-OFFICE.

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

It is pleasant to watch Mr. F. S. Oliver in Ordeal by Battle (Macmillan) hammering upon the noses of his and his friends' enemies, or gaily drawing the fangs of his particular black beast, the political lawyer, and to reflect on the charming appositeness of that honoured pseudonym Pacificus. But in truth one cannot jest about this profoundly serious book. Here is a writer who is abundantly justified by the result in breaking the silence of that loyalty which constrains even the most talkative and critical of us plain men a writer who can classify and summarise his political thinking in swift phrases which have the bite of epigram with a wit and precision Gallic rather than British. Yet not its wit or its lucidity but the fire and sincerity of it make this book. Of necessity hurried, it is neither hasty nor glib. Behind it lie the thoughts of strenuous years. There is anger in it, but not a mean or a cheap stroke. With more truth than such heroic simplifications usually possess he sets before us the German system as, essentially, the domination of that always baleful thing, the priesthood in politics—that is of the highly skilled and drilled "pedantocracy" with its irrevocable dogmas and surrender of all critical judgment; our own British scheme as, in effect, the creation of the dominant lawyer, not so much corrupt as corrupting; cognisant rather of precedents, ordinances, appearances than of realities; adroit in debate, hectoring in cross-examination; a seeker rather after verdicts than truth; hesitating in action; a man not of affairs but of aspects of affairs. Neither party is spared. Some distinguished personalities are faithfully dealt with. He pleads that we have been given (are being given) the stone of lawyerism when we hunger for the bread of leadership. He criticises with a welcome frankness the incredibly futile reticences, the unmeasured distrust of the people, the empty-smooth phrases of the politicals—such, for instance, as "the triumph of the voluntary system." If we win it will not have been any triumph of what may reasonably be denied the attribute "voluntary" and is most certainly not a "system." "The triumph of the voluntary system," said a French officer "is a German triumph; it is the ruin of Belgium and the devastation of France." Perhaps if there be any spleen in this book it is directed against those who not merely ridiculed but denounced the great soldier who warned them of this "calculated" war and the price of averting it. Do they make any amends, register any confession of mistaken judgment? Let me as one who humbly a fought in their camp and murmured their shibboleths answer regretfully for them. They do not. Mr. Oliver makes us see ourselves as we are seen. His book is a flame that will burn away much cant and rubbish; it will "light a candle which will not soon be put out."

It is not usual to notice books of verse in these limited columns, but the appearance of 1914 and Other Poems (Sidgwick and Jackson) seems an occasion on which a departure from this rule may fittingly be made. Of this little volume, which contains the last things written by Rupert Brooke, it can be said at once that no one who is cares for the heritage of our literature should omit to read and possess it. Inevitably from the circumstances in which the collection has been made it includes work of unequal value, some of which perhaps the poet himself might have wished to amend. But of the best of it, and especially the five already famous sonnets with which it opens, one can only repeat a criticism made upon their first appearance: they will rank for ever among the treasures of English poetry. Even to-day we can be grateful that the writer lived long enough to leave behind him a memorial of such dignified and noble beauty. Not that the book is all solemnity. No record of Rupert Brooke could forget his laughter; it sounds delightfully through the buoyant audacities of "The Fish's Heaven;" more gravely through "The Great Lover," where he tells over the list of pleasant things that have delighted him, much as Whitman might, but less laboriously. To generations unborn Rupert Brooke will become a tradition, another figure in the group of poets whom the gods loved and crowned with immortal youth. "The worst friend and enemy is but death," he wrote, facing with happy courage a fate of which he seemed to have fore-knowledge. To himself death may have come as a friend indeed, but to us as an enemy whom it is hard to forgive.

A long study of tales of crime and detection has led me to the proud conclusion that I am not easily to be baffled by their mysteries; so it is incumbent upon me to confess that Sir A. Conan Doyle, in The Valley of Fear (Smither, Elder), has fairly and squarely downed me. The first of his tales is called "The Tragedy of Birlstone," and here we have as rousing a sensation as the greediest of us could want, and Sherlock Holmes solving the problem in his most scientific manner. In the second tale, "The Scowrers," the scene of which is laid in America, we have the story of a society which devoted itself to murder and crime, and we discover why Mr. Douglas, a Sussex country gentleman, was concerned in the Birlstone Tragedy and was also a doomed man. "The Scowrers" is rather overcharged with bloodshed for my taste, but in spite of this I can only praise the skill with which a most complete surprise is prepared. Respectfully I take off my hat to Sir Arthur. In addition let me say that dear old Watson is actually allowed a short but brilliant innings, for I can imagine no finer achievement on his part than to score one off Sherlock, and this for a fleeting moment he is permitted to do. (Cheers.)

"The editing of King Edward VIII., in the series of the 'Arden Shakespeare,' published by Messrs. Methuen & Co., London, at 2s. 6d. net per volume, has been committed to Mr. C. Knox Pooler."—Scotsman.

Is not this perhaps a little previous?