Page:Punch Vol 148.djvu/574

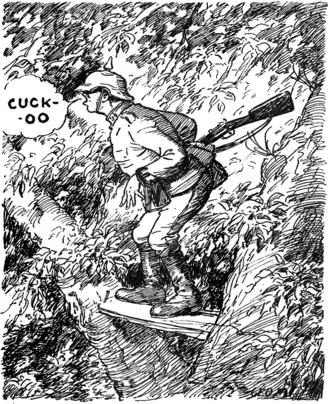

Artful device resorted to by a German sniper who thought he was observed.

OUR BOOKING-OFFICE.

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

I am not quite sure that we haven't had enough of white-hot War-books. All that can be said without further, and as yet unavailable, evidence as to the causes of the Great Tragedy has been said by many competent men, and perhaps in fewer, though certainly not more eloquent, words than by Sir Gilbert Parker in The World in the Crucible (Murray). And yet I think these forceful vigorous pages will find many readers and drive home some terrible convictions. Our new baronet's method of select quotation from adversaries is open to the objection attaching to all work of the sort, that it raises a certain kind of doubt in the fair-minded reader. No doubt one might find some German book composed exclusively of hot-headed and very yellow utterances by Englishmen, arranged as a complete justification of this "Preventive War," or proving guilty machinations on the part of Albion the always perfidious. The best part of the book is the summary of German war crime, from the beginning of August last to the sinking of the Falaba; and the significant reminder of the fine chivalry with which Japan and Russia conducted their desperate struggle in the opening years of the century. Said the Japanese officers to Sir Ian Hamilton when he congratulated them on the conduct of their men: "We cannot afford to have any people connected with this army plundering or illtreating the inhabitants of the countries we traverse." While of the Russians he wrote: "The Muscovites haven't lifted so much as an egg, even during the demoralisation of a defeat." That is the answer to those sensitives who sit apart and murmur, "All war is terrible," with the implication that the kind waged by Germans is no worse than the others. It simply isn't true, and because it isn't true there are old and stodgy merchants who have never done anything more adventurous than miss the 9.45 up-train, yet, if there were any talk of premature peace, would be clamouring to be sent across the Channel in protest to the death.

I think I ought to warn you against prejudging The House of Many Mirrors (Stanley Paul) by the picture on the cover. The pale man with staring eyes who is holding up a lamp depicts indeed the hero of the tale, but the actual circumstances are not so melodramatic and creepy as their presentation suggests. Indeed, though there is drama, and grim drama, in Miss Violet Hunt's latest story, it is not of the sensational kind. It is a story of a woman's self-sacrifice, and as such has done much to strengthen me in a previous conviction that self-sacrifice can be one of the most terrible forms of selfishness. Consider the facts. Rosamond Pleydell, a woman of the idle, not quite well-enough-to-do set, loved her husband, whom she supported out of her own income. The husband was one as one of several possible heirs to an old uncle, but was supposed to have lost his chance by marrying Rosamond, the betting being strongly in favour of Emily, a female cousin, who had been sent to look after the old man—in more senses than one. Rosamond, finding herself stricken with mortal disease, and knowing her death would leave the man she loves without his little comforts, conceals her state, and, having persuaded him into a protracted visit of ingratiation to the will-maker, herself goes off abroad to die alone. She even prepares a batch of cheery letters, to be sent at regular intervals before and after her death, in order to keep the husband from deserting his task. Naturally when, having got the inheritance (and incidentally complicated matters by falling in love with Emily), he finds out the truth, he suffers as any woman who cared for him could surely have foreseen. My admiration for Miss Hunt's real cleverness of style made me sorry that she has wasted it here—and not for the first time—upon a sordid tale of unpleasant people.

Tares (Chapman and Hall) is the name that Mr. E. Temple Thurston has given to a collection of short stories and sketches. To save you from a wholly unjustifiable misapprehension, I should perhaps explain that the title is simply taken from that of the first story in the book, and has no reference to the general character of the whole. "Tares" itself is a very well made and poignant little sketch of certain events in Malines, centred in the historic and terrible pronouncement made from the pulpit by a priest of that town. Both here and elsewhere in this book Mr. Temple Thurston has shown himself able to write about the War with passion and yet with dignity and restraint. A rare gift. There are other sketches, semi-satiric studies of the female character divine, which are of more unequal merit. Some of them, to be honest, hardly seem quite to have earned their place. The best of the humorous batch is the last, a story told with delightful humour of an engaging idiot named Cuthbertson, who thought he could box and was tempted into a Surreyside ring—with disastrous consequences. I liked especially the touch which depicts him, confronted with the peculiar aroma of the dressing-room, and observing that it was "a bit niffy"; though, as the author points out, "this was not his usual method of speech. He was doing as the Romans do in Rome." Perhaps Mr. Thurston won't thank me for saying that I place some of the contents of this modest volume much above his better known novels. But I do

A selection of the verses which have appeared on the second page of Punch during the War has been published by Messrs. Constable at 1s. under the title War-Time.

More Commercial Candour.

Draper's notice in the middle of a sale week:—

"I have no guarantee that these blouses will last till Saturday."