Page:Punch Vol 148.djvu/560

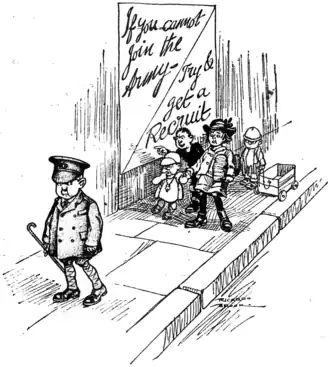

Voice of Envy. "Garn! 'E ain't no real Bantam! They jest dressed 'im up to kid blokes wot fink they're too little to join."

THE WATCH DOGS.

XXI.

My dear Charles,—Perhaps it is that I have not been quite myself lately; at any rate, whatever the inner cause, a change has come over me and I am no longer able to suffer fools gladly. Between ourselves, I have conceived the utmost dislike for these Germans, a dislike which is all the more remarkable since I happen to be fighting some of them at the moment, and I'm sure that to fight against people is to get to know them better and to appreciate all their good points. However insufficient my data may seem to be, I am convinced that these Teuton fellows are quite impossible, their manner atrocious and their sense of humour nil. I surmise that at their officers' mess they overeat themselves methodically four times a day, making nasty noises. I suspect them of having very ostentatious baths in the morning, at which they are offensively hearty, and yet really, if the truth were known, only wash the parts that show. I can picture them talking exclusively about themselves, shouting down each other and putting such a mixture of superior virtue and patronizing joviality into their morning greetings that the genial and kindly "Gott strafe England" becomes little more than a sullen menace to the addressee. And if they ever do stumble upon a joke, I am quite certain they repeat it ad nauseam and end by quarrelling about its inner meaning. All this I have gathered from the noises they make behind their parapet, and the way they shoot or don't shoot at us. Possibly there is one little group of better men in the middle, by the ruined farm-house, whose sympathies are all with us and who shoot at us only because they must shoot at something, being at war, and cannot shoot at their own people because it would crick their necks.

Having been driven to this opinion of the enemy I have been reluctantly compelled to put a little frightfulness into my personal campaign. With the kind assistance of my men, I have been able so to arrange our rifle fire in my platoon that, at the busy time when everybody who is anybody is firing, every five rifles make a tolerable imitation of a maxim, thus giving the enemy the impression that we have twelve machine guns per platoon, that is one hundred and ninety-two to the battalion. At other times we do an organised sulk, refusing to fire for hours at a time. Nothing is more trying than a silent foe; he's bad enough when he's shooting, but when he's quiet he's very likely preparing something more dreadful, possibly coming across to you in the dark to stick a piece of cold steel into you. And so we get him thoroughly nervous and craning much too far over the parapet, and then we suddenly recover our good spirits and burst into a very rapid fire of our own invention, to a merry sort of syncopated beat.

Another way to punish Germany (by human agency) is to take a couple of dozen empty tins, fill them half-full of stones, tie them together, leaving a very long tail-piece of string, and send the whole out, in the dark, to be placed by an audacious and impudent patrol amongst their barbed wire. You then wait till the quiet time of the next day, and when you think you've got your enemy just dozing off you give the long string (which your patrol brought back) a series of spasmodic pulls. You can always judge the extent of your success by the mileage of artillery, of all weights and diameters, which your simple device sets in motion.

I can offer you another suggestion for what it is worth. About once a fortnight I send up a flare in broad daylight before breakfast, and my accomplices carry the signal along the line by doing the same at intervals. In civilian life fireworks by day serve no useful; but in war time their very incongruity and inexplicability give them a sinister air of mysterious import. To us these signals mean nothing; to the enemy they suggest, I hope, the very worst, in whatever shape their guilty minds may conceive it.

Our best effort was quite unintentional. A subaltern (whom I will not advertise by name, since goodness knows what he'd be doing next if I did) came into possession of a new kind of automatic pistol; he is always coming into possession of a new kind of something or other, and must always try it forthwith. In the absence of available targets upon which we could see the hits, he had the original idea of proceeding down the sap which runs out in front of our parapet, and shooting from there at the lonely tree in the middle of the beyond. He was followed by eight other subalterns, who were by no means prepared to admit the superiority of this pistol, for all its newness, over their own weapons in the matter of speed. I do not include in the official starters either D'Arcy or the machine-gun officer who dragged out a maxim to set the pace. D'Arcy's revolver has all the distinction of being an heirloom and all the disadvantages of capricious senility. It is at present on strike, but he refused to be left out of the competition and turned up with a hand-grenade to provide, as he said, the comic relief... It was a good start, and for sheer rapidity easily surpassed anything in this or any other war. We were so pleased with the affair from our own point of view that we forgot all about the Germans and their point of view. For a long time after it they were obviously irritable and nervy. It didn't occur to us that of course anyone would be moved by so sudden, terrific and peculiar a noise, which would have been bad enough if it had come from our parapet, but must have been intolerable when arising, as it did, from what was supposed to be the unoccupied midst of a well-known and highly-respected turnip-field.

Anything annoys them now. Even our singing God Save the King and cheering loudly, with caps raised on bayonets, on the occasion of His Majesty's birthday, raised a storm of indignation expressed in rifles, mortars and Jack Johnsons. I cannot understand their feelings; however German I was myself I should regard such a question as the enemy's own business and not mine and leave him to it and