Page:Punch Vol 148.djvu/554

in subsequent events belongs, for the little it is worth, not to Langton but to John Inglis, who had known the first Mrs. Langton, and, meeting Miss Tancred at Palermo, tries to induce her to surrender the necklace, and incidentally falls in love with her. There is besides some matter of hypnotism, of no moment, and even the pearls fail to provide anything more thrilling than a muddled incident, which may have been meant for burglary on Inglis' part, but only confused me as to his integrity. Mr. Squire shapes and polishes his material prettily, but I express my hope that he will put a little more stuff into the next consignment.

Humour is such a subjective and unstable quality that a book which professes it must always be faced by the reviewer with some diffidence. From this start you may perhaps guess already that I have found myself baffled by Windmills (Sekcker). Frankly, this is so. Still more frankly, the book not only bewilders me, but causes me a feeling of distress, the more acute because it is signed by so distinguished a name as that of Mr. Gilbert Cannan. How far it is still permissible to be facetious about the War may, I suppose, be a matter of opinion. But, if one must poke fun at it, the least and lowest test is that it should be amusing, and this is precisely what Mr. Cannan's dreary absurdities about "Fatland" and the "Skitish Empire" do not even begin to be. There are other satires in the book, one of which, "Out of Work," is not without beauty. Another, which I will not specify, appeared to me simply disgusting. I am sorry to have to use so painful a candour about a writer of Mr. Cannan's known artistry. But the fact remains that Windmills seems to me a foolish little book, by no means free from offences against what I might call (with no flippant intention) the elementary canons of good taste.

If many more authors take to telling their tales in consecutive books, publishers will have to adopt some kind of synopsis, on the you-can-start-now system. For example, in The Invisible Event, you need a little previous knowledge of the circumstances to understand why Betty is discovered so greatly worried about what answer she is to give Jacob. Of course, however, if you are familiar with the previous books of Mr. J. D. Beresford (as you should be by now, if you are concerned for the best in modern fiction), you will remember that Jacob has just asked Betty to manage and share his life—and this though there was a discarded but undivorced Mrs. Jacob still in the background. The present volume, which is the last of the Jacob Stahl trilogy, tells you what Betty did, and what sort of thing she and Jacob made of their joint existence. Like the other two, it is a piece of work remarkable for a rare gift of insight into personality. The relations between the only two characters that matter are realized with extraordinary truth and detail. One is tempted here, as in all these photographically realistic novels, to wonder how much is autobiography. Mr. Beresford indeed deliberately provokes this temptation by making his hero a novelist, and (rather less excusably) by causing The Morning Post to review Jacob's first novel in precisely the words of the notice of the author's own previous work in that journal, printed here by Messrs. Sidgwick and Jackson in their advertisement pages. As a reviewer I am by no means certain that I approve of this hauling of a brother craftsman out of the critical stalls and over the footlights. That, however, is a small point. Waht matters more is that The Invisible Event justifies those who have saluted Mr. Beresford's earlier volumes as the work of a distinguished writer.

I have an idea that Mr. and Mrs. Hugh Fraser intended me to find points to admire in some of The Pagans (Hutchinson), but I confess that they seemed to me one and all very unpleasant people. Even Nita Hardwick, who "carried her own atmosphere with her," a "spiritual perfume," indulged quite freely in a quantity of minor lies and meannesses which she could fairly easily have avoided, though she showed a dislike of the grosser misdemeanours of the extremely smart circle in which she moved. Tressida Sackwood, on the other hand, infinitely beautiful and intent only on her own game, was a much more thorough-going person, though rather after the manner of a newspaper feuilleton. Then there was a handsome retired naval officer, Tom Carew, the only man whom Tressida had ever loved (Lord Sackwood was an absolute waster, and in any case, being her husband, would hardly have counted). Tom fell deeply in love with Nita, and being unwilling either to give Tressida away or to lower himself in Nita's eyes vainly tried to arrange to be on with the new love without the old love's noticing anything. I was not sorry that he failed; but he did so more dismally than I should have expected in a man of some wits and a good deal of experience. The real dramatic intent came at the end. Tom Carew, who was a widower, had a daughter, who loved and was loved by his friend Cochrane. Forgiven at last by Nita for his offence and its concealment, Carew was brought suddenly up against the same offence in Cochrane, lately freed from Tressida's toils. Could he too forgive? The authors stated this more painful problem, but it was obviously impossible for them to deal with it in a book of this kind, where the whole thing is on the melodramatic rather than the tragic plane. The conclusion therefore hardly cleared things up. But I was not really keen enough on any of the people to care very much.

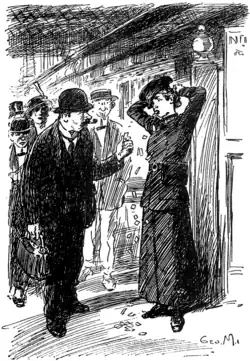

A Railway Ticket Collectress has an unhappy moment with her coiffure.