Page:Punch Vol 148.djvu/551

provincial in the matter of these accessories.

I cannot close without warning my friends to take their respirators with them when they go to view Armageddon, for there is an asphyxiating shell (three-inch and French) which penetrates the German Headquarters and reduces its occupants to a condition of permanent coma (painless, you will be glad to hear), in which they preserve the attitude of the moment; and its fumes achieve the object of all dramatic art, which is to get across the footlights.

O. S.

"The Angel in the House."

What ought a critic to do when he finds by the continuous ripple of laughter throughout the performance that a play is obviously more attractive to other people than to himself? First, perhaps, to examine the condition of his liver; and next, if he finds nothing amiss there, to ask himself, like the fox-terrier in the advertisement, "What is it that Master likes so much?" Messrs. Eden Phillpotts and Macdonald Hastings, the authors of the new comedy at the Savoy, owe a good deal of their success, I fancy, to the all-round excellence of the cast, the skill of the "producer," and the brightness of the First Act. We are introduced to a fine old English family in a fine old English country house. Sir Rupert Bindloss, Baronet and widower, is one of those benevolent and slightly eccentric old gentlemen whom Mr. Holman Clark plays so well. His household consists of two charming daughters (Miss Vera Coburn and Miss Mary Glynne), their fiancés, and their chaperon, Lady Sarel. But it is presently increased by the Hon. Hyacinth Petavel, son of an old flame of Sir Rupert's, and commended by his mother in a letter written in articulo mortis as "an angel in any house." Preceded by a quantity of luggage, including a parrot, and accompanied by three lapdogs, Hyacinth arrives. He proves to be "a mother's darling" of the most pestilential variety—selfish, hypochondriacal and opinionated—and at once shows his intention of taking command of the family.

In the Second Act, a fortnight later, we find him fully installed as domestic tyrant, with all the household, save the two young men, at his feet. Sir Rupert has acquiesced in the alteration of his meals, the disfigurement of his garden by "topiary" monstrosities, the keeping up of gigantic fires in August, and the banishment of his family portraits and Greek busts in favour of Futurist productions, on which Hyacinth lectures at interminable length. He even persuades the girls that in the interests of Eugenics and the "unborn" it is their duty to break off their engagements and exchange lovers. This is the last straw. The young men plan revenge.

The Third Act finds all the party picnicking at the Temple of Eros on an island in the lake. The lovers arrange that Hyacinth and Lady Sarel shall be left stranded as night falls, reckoning that the "angel's" susceptibility to cold and Lady Sarel's obvious penchant for him will bring them together. So it falls out. A capital scene, in the course of which Hyacinth consents to borrow her ladyship's flannel-petticoat, ends in his proposing marriage on account of her "beautiful temperature." Lady Tree gives an admirable portrait of the amorous widow, and Mr. Irving is absolutely lifelike—in the Second Act I found him almost too lifelike—as the bore. The play would be improved if it were taken a little more quickly, and if the "angel's" speeches were slightly curtailed. Some of the "eugenic" jocosities could perhaps be spared with advantage, though I am bound to say that the audience seemed to enjoy them.

L.

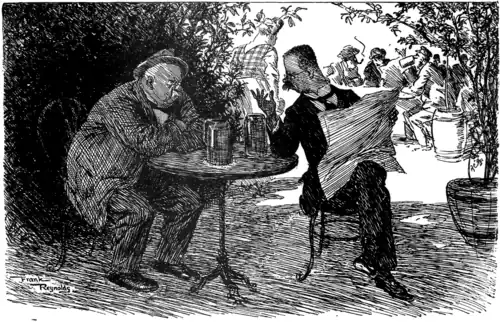

"My friend, I don't like the look of things. They mean business. No one in England now kicks the cricket-ball."

"The French official report shows that the weather has stopped fighting."—Daily Mail.

It is good to hear that our most dangerous enemy is hors de combat. But for how long, we wonder?