Page:Punch Vol 148.djvu/550

AT THE PLAY.

"Armageddon."

THE JACKDAW OF RHEIMS.

Abbé of Rheims Mr. Martin Harvey.

Von der Trenk Mr. Charles Glenney.

In his series of tableaux parlants Mr. Stephen Phillips conducts us on a kind of Rundreise, or circular tour. Starting from Hell and returning to Hell, we assist at the bombardment of Rheims; a domestic scene in an English orchard; the operations of the Official German Press Bureau; and the capture of Cologne by the Allies. Imagination, you will gather, is brought into perilously sharp contrast with the realities of to-day; and it is not confined to the realm of Satan, but permeates the Headquarters of the 5th German Army Corps before Rheims, where the types are almost incredibly un-Teuton in appearance.

In two of his more practical tableaux the author wisely resorts to prose. A third scene, where an English mother learns of the death of her son in action, lends itself more easily to poetic treatment; yet even here we are conscious of the old incongruity of blank verse as a medium for the emotions, however elemental, of the hour that is. The verse suffers by its association with actuality; and the realism of the drama suffers by the literary form in which it is conveyed. The most unlikely people are made to poetize on Hellenic lines. Thus the mother and the girl who is betrothed to the soldier-son hold a sort of antiphonal competition, like the half-platoons of a Greek chorus, on the splendours of military service; and later, when they have heard the tragic tidings (delivered in prose by the boy's late tutor), and are both broken with grief, they start a fresh argument on their comparative claims to the crown of sorrow.

But in the fourth of the terrestrial tableaux there was a chance for heroic declamation. It is true that you might not expect the Generals of the advanced armies of France, Belgium and England to utilize the occupation of Cologne for the delivery of a résumé of the motives actuating their respective countries. But the conditions may be allowed to pass for the sake of the noble eloquence with which the French and Belgian Generals (and in particular the latter) claim the avenger's right to sack the city. The English General, pleading the loftiness of England's cause, opposes himself to their passion for reprisal; and, though shaken by news of the death and mutilation of his own son, reiterates his resolve to forgo revenge, and is confirmed by a vision from the unseen world (Heaven, in this case). The purpose served by the apparition (it was Joan of Arc in full armour) might have had some plausibility if she had presented herself to the French, and not the English, General. And so it was in the original book; but when I tell you that the actor-manager took the part of the Englishman you will understand the reason for this disastrous substitution which was the ruin of the scene. For, apart from the unfortunate relations established a few centuries ago between Joan of Arc and the English, General Murdoch was already inclined to a policy of humaneness, whereas General Larrier stood in plain need of conversion.

The scope for humour—humour, that is, of intention—was naturally limited in a play about Armageddon. But Mr. Phillips found a fairly easy and obvious occasion for it in the scene of the German Official Press Bureau. It had been foreshadowed by Belial, "Lord of Lies," who, along with the shade of Attila, had, in the Prologue, been given a commission on the Headquarters Staff of Hell for the period of the War. His claim had been advanced in the following words:—

In such assembly, and appear to jest,

Remember, in losing humour we lose all;

The thought provokes a spiritual sweat."

So now we know where the Spirit of Comedy comes from. For the humour of Hell is apparently cosmopolitan and not merely Germanic. One catches a hint in it of the manner of our own censorship. Thus:

Belial. I am content that this report go forth,

But hold myself no way responsible."

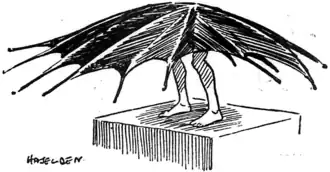

I don't know Satan really well, in a personal sense, and so cannot say whether Mr. Martin Harvey was a good imitation of him. But I gather that the Master of Hell wears fewer clothes than his subordinates and talks enormously louder than anybody else. His long pointed wings—faintly suggestive of a butterfly existence—afforded good cover when used as an umbrella to keep out the searchlight of Heaven. For the rest, the author made a brave show with his arch-devil, though perhaps a little conscious of the literary effort that was asked of him in view of the fact that Milton had already passed that way.

Satan (Mr. Martin Harvey) takes cover from a searchlight.

The play, as always with Mr. Stephen Phillips' work, contained some great lines, and the actors, with one or two exceptions, did justice both to rhythm and rhetoric. Best, perhaps, was the passage, finely delivered by Mr. Fisher White, in which the Belgian General, clamorous for revenge, rehearses the wrongs of his country. Herr Weiss, Director of the Official German Press Bureau, was almost the only alien enemy who succeeded in suggesting his origin, and Mr. Franklin Dyall was excellent in the part. Mr. Cooke Beresford, as his First Reporter, whose business it was to manipulate the lies about London, was quietly effective. Mr. Glenney, as Count von der Trenk, was blustering and brutal, but might have come from anywhere but Germany. Mr. Edward Sass was very sound and workmanlike as General Larrier, and so was Miss Mary Rorke as an English matron.

Also a word of compliment must be given to the brief performance of Miss Maud Rivers (as a French peasant-girl), who cleverly skirted the fringe of melodrama. As for the supers, Mr. Martin Harvey was always a little