Page:Punch Vol 148.djvu/512

AT THE PLAY.

"The Day before The Day."

I only wish the stage were a mirror of life in the matter of the spy śpied-on; for in Mr. Fernald's new play, as in The Man that Stayed at Home, the alien enemy within our gates is gloriously confounded. In the present case he is not defeated by superior wit; the author relies upon the superb bravado of his hero and the no less superb credulity of his audience. Between the two of them they bring about the collapse of a diabolically ingenious organisation.

The plot was not so clear in detail as we should have liked it, but we never permitted this defect to cloud our confidence in a happy issue. For on a happy issue depended not only the existence of our nation, but the author's chance of a run for his trouble. All the same we were kept in a right state of tension for two-thirds of the time.

The chief notes of the play were revolvers and musk. Musk was the scent worn by the envelopes which contained the letters written by von Ardel of the Prussian Guard to an English girl, Victoria Buckingham, who had once been engaged to him. The interception of one of his letters had laid her under suspicion, and von Ardel's idea was to bring about a meeting with her on the strength of their former relations, and to place in her hands a false plan of invasion which would be sure to fall into the clutches of the War Office and put them on the wrong track—Northumberland, in fact, instead of Kent. The envelopes in which his secret instructions arrived were strewn all-over the stage, and one could almost sniff the asphyxiating perfume of their musk in the tenth row of the stalls.

A STAGE BARRIER

Max von Ardel Mr. Gerald Lawrence.

Victoria Buckingham Miss Grace Lane.

Guy Howison Mr. Lyn Harding.

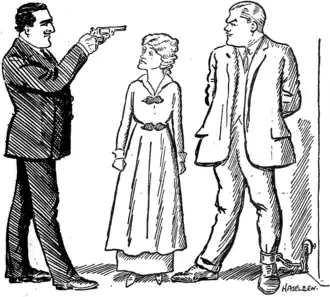

As for the revolvers, it is a long time since I have seen so many whipped out at one moment. The only one amongst the spies who never could get his weapon out in time was an American, and you would have expected him to be the handiest of them all. Fortunately, not a single revolver was discharged, except "off" and between the Acts, so that the report of it only reached us verbally. But there was a period, that seemed interminable, during which the only thing that intervened between von Ardel and his target was the frail form of a woman—an obstruction that a resolute man ought easily to have circumvented. Nothing but the fact that he had other designs for the lady could have deterred him—being a Prussian—from letting the bullet take her en route.

The first scene of the Second Act was extremely well done. It gave us the East Coast haunt of the spies—a member of the Prussian Secret Service, a stockbroker, a German-American and a Professor of Infernal Mechanics. They talked German and English alternately with equal ease, though the Professor felt it incumbent upon him to correct the American's pronunciation of the ch in ausgezeichnet.

The scene flattered the German spirit, showing its thoroughness, the intensity of its purpose, its readiness to sacrifice the individual for the cause, the iron discipline which directs its licence and organises its passionate hate. The man who came out of it worst (for Mr. Fernald is not very tender to his countrymen) was the American Schindler, who never got much farther than a protest against brutality to women, and a hint of what his nation might do if it was annoyed. "You're not a nation," said one of the Germans, "you're a mass meeting."

The second scene (unchanged) of this same Act was a little dragged out. For a long time Captain Howison, the British Intelligence Officer, has nobody to talk to on the stage. He has been left alone in the dark, gagged and bound and riveted to the wall. With his free foot he reaches a chair and rubs his and gag off on one of its legs. With the additional breath thus acquired he reaches a table, and luckily finds a knife in the drawer of it, and so cuts the ropes that hold his arms. With fresh prehensile power he now reaches a long pole with a hook to it, fishes a box from across the room, finds it contains the very tool he wants, and unrivets his leg. All this took time, and so did the long interval, largely devoted to the levelling of revolvers, before he could get to grips with von Ardel.

But Mr. Lyn Harding was equal to his responsibilities and kept us alert. Indeed he shone in action much more than in speech. Twice he was called upon to cope with improbable conditions. When, in the First Act, he suddenly returns from the dead (out in Alaska) the author provides him with no argument (except his falsely-reported death) by which to explain to the lady of his heart a two years' unbroken silence. His manner was abrupt and halting, and you wondered a little why he was selected for the Intelligence Department. In the Second Act, again, when he appeared, unarmed and unannounced, among the gang of enemy spies, his method of introducing himself was extremely unconvincing, and it seemed incredible that he should not have been shot at sight with all those revolvers about, or at least have been thrust into the Professor's electric crematorium under the stage.

The honours of the evening went to Miss Grace Lane, who played the part of Victoria Buckingham with a most compelling sincerity. From the first there was need of great candour on her part to disarm the suspicions both of her friends on the stage and us in the audience. But Miss Lane made an easy conquest of all the hearts that were worth winning. Of the spies Mr. Frederick Ross, Mr. Nigel Playfair and Mr. Edmund Gwenn were horribly German. Mr. Gwenn indeed might have been the author of the Hymn of Hate. But Mr. Gerald Lawrence, as von Ardel, lacked something of the true Prussian manner, and had not even taken the trouble to disguise himself as a 'blond beast."

The return of Miss Stella Campbell (playing a quiet American woman, loyal to the land of her adoption) was very welcome; and Miss Chesney seized her brief chances as a British hostess with admirable effect. Of Mr. Dawson Milward and of Mr. Owen Nares, who