Page:Punch Vol 148.djvu/473

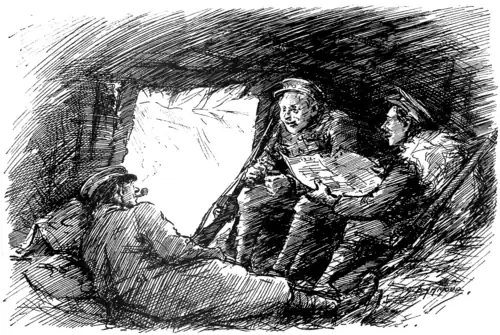

THE BUDGET AT THE FRONT.

First Tommy (reading belated news.) "Looks as if them poor beggars at 'ome may have to pay six bob a bobble for whisky."

Second Ditto. "Well, thank Heaven, we're safe out here."

OUR BOOKING-OFFICE.

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

Except that a distinguished author is entitled to have his joke like everybody else we do not quite see why Mr. H. G. Wells should have disclaimed the authorship of Boon, the Mind of the Race, etc., etc. (Unwin), in the "ambiguous introduction" he has prefixed to that work. Boon was a popular novelist, with a great vogue among American readers—Aunt Columbia he calls them collectively—and a profound contempt for the work that brought him in the dollars. The things he really wanted to write were skits upon his contemporaries, new systems of philosophy, and so forth; and here we have them in his literary remains, as prepared for publication by his friend "Reginald Bliss," a writer with whoso previous work we are regrettably unfamiliar. The whole is set forth with the assistance of subsidiary characters who act as a foil to Boon in the manner of Friendship's Garland and The New Republic. The brightness of Matthew Arnold's famous jeu d'esprit will hardly be dimmed by the new competitor, nor has Mr. Mallock much to fear from it, but the chaff of Boon's fellow-craftsmen is sometimes excellent. Occasionally it is embellished with thumb-nail sketches, the best of them being the caricature of Dr. Tomlinson Keyhole, the eminent critic who when he suspects a scandal "professes a thirsty desire to draw a veil over it as conspicuously as possible." If Mr. Wells should find himself in trouble over these indiscretions and plead ignorance, he must expect to be told that ignorance is Bliss, and Bliss is ———.

All the pleasant things that I have said in the past about the work of Mr. Henry Sydnor Harrison I should like now to repeat and underline after reading Angela's Business (Constable), which seems to me quite one of the best samples of fiction that has come to us over the Atlantic for a long tine. Perhaps it may not enjoy the widespread popularity of the same author's Queed; but there is no question of it as a book to be read. I will not tell you the story; though even if I did it wouldn't greatly matter. Briefly speaking, "Angela's Business" was to meet the demand there always is in the world for nice, normal, not too intellectual girls; more briefly still, it was to marry the first eligible man to whom these qualifications appealed with success. Angela was a home-maker. In the book we see her and her lifework through the eyes of a young man, Charles Garrott; and the argument of it is a contrast—one might almost say a competition, though unacknowledged and unconscious—between Angela's methods and those of another woman, Mary, the independent, wage-earning career-maker. Incidentally, a story of American town-life in which none of the characters is beyond the need of financial economy has a novel and refreshing effect. But there is any quantity of refreshment and novelty in the style also. Mr. Harrison has a quality in his writing that I can best catch by the epithet "sensitive." While preserving his own impartial, slightly aloof attitude towards his characters, he is quick to respond to every shade of change in their relations with each other. There is, too, a very lively and engaging wit about him. He writes American undisguised, and you may even be astonished, in your insular way, to find what a capable and vigorous medium he can make of that quaint language. Altogether Angela's Business must certainly be everyone else's also.