Page:Punch Vol 148.djvu/429

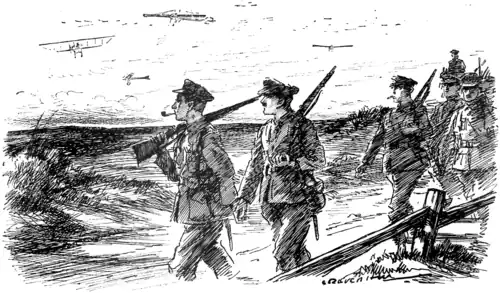

Tommy (on Salisbury Plain). "Mr, Bill! Ain't they tame round 'ere?"

THE EVER-ALERT.

I met my old friend the leader-writer on his way to work. His eye flashed his brow gloomed, his powerful jaws were set, his step was firm and determined. Shelley's lines floated into memory:—

I beheld, with clearer vision,

Through all outward form and fashion,

Justice, the Avenger, rise."

The third rhyme may not be quite up to modern standard; but the spirit is there, and it was the spirit that affected me. I felt that I too was in the presence of something very like Fate.

"What ho!" I said. On the warpath?"

"If you mean, am I going to the office? yes," he replied.

"Going to let some one have it hot?" I continued.

His demeanour increased in vehemence. "Of course," he replied.

"Who is it this time?" I asked. "Who is the last tired official who, after months of hard work and anxiety, has failed to reach your high-water mark and must therefore be lashed in public."

"I shan't know till I get there," he said. "There's certain to be some one. But how did you guess?"

"Not difficult," I replied. "Your very look showed me that. I can see that your duty is as plain to you to-day as it was yesterday and always has been. But for you and your punctual pen I don't know where England would be?"

His sternness relaxed. "I'm glad you think like that," he said.

"I do," I replied. "I think England was never to be so felicitated on her Press as to-day. Her leader-writers were never so vigilant for defects in our administration or so instant in proclaiming them for everyone to see."

He beamed.

"I hope so," he said. Then a shade of anxiety flittered over his brave stolid countenance. "You don't think there's any danger of our striking the rest of the world as a nation divided against itself, do you?" he asked.

"My dear fellow," I assured him, "what a ridiculous idea!"

He seemed to be relieved.

"The truth is above all," he said.

"It is," I replied, "far above. Out of reach for most of us, but never inaccessible to the grave and sagacious Press. You journalists know. All is simple to you. There are no complexities in administrative work. Black is black and white is white when one is governing a country, and there are no half-tones as in all other walks of life. Every mistake must be branded; no one's good faith must be trusted; no one in a difficult position must be helped. Don't you agree?"

"It is a mighty organ," he said. "I think that the importance of the Press as a critic of those in power cannot be over-estimated."

"With its eye and ear at every hole and all its agents busy, it must obviously know so much more about a department than the department itself," I said.

"Of course, he replied; "and in addition it frames standards and ideals of perfection by which it measures all those in authority; any falling short must be castigated."

"Immediately," I said.

"And without mercy," he added.

"In war time and under such a strain as the country is now experiencing you cannot be too drastic," I said.

"Exactly," he said. "There is more at stake; the Press has a sacred duty."

"Is all the Press equally sacred?" I asked. "Are the racing forecasts, for example, as sacred as the leaders?"

"Nothing is so sacred as the leaders," he replied. "Next to them the correspondence columns, where all kinds of scandals and abuses are ventilated and other attacks not necessarily less merited are made on those in whom the responsibility for England's success is vested."

"But what about the news?"

He fumed terribly. "There is hardly any news any more," he said. "The Censor in his benighted besotted folly..."

But I did not wait to hear the rest of the leader.