Page:Punch Vol 148.djvu/408

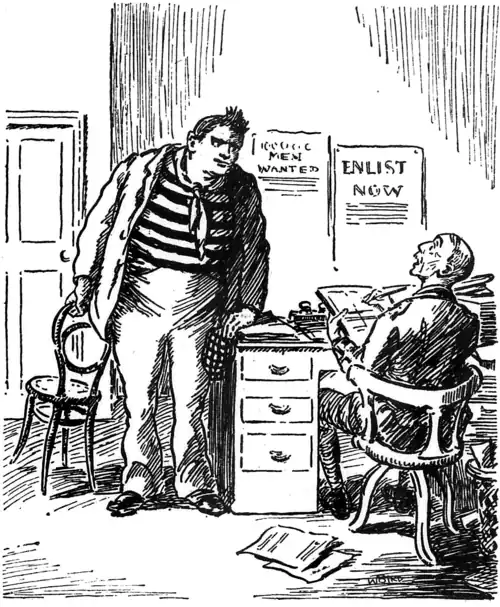

"I'd like to join the flying corps."

"What!"

"Oh, I mean the chaps wot 'olds on to the flying-machine while the pilot gets into it."

REST CURES.

An Innovation.

We were discussing rest cures, and everyone had a special kind to recommend.

One said that there is nothing like bed. Bed for a fortnight. But that seems to me to need great strength of mind. Personally, my horror of bed after the sun has begun to knock on the windows is only equalled by my desire for bed as the hands of the clock draw near the hour which our lively neighbours (and allies) call Minnie.

Another advised Cornwall and no newspapers. There is something to be said for this scheme. If there were no newspapers, life would be restful automatically. It is the news that wears us out. The advanced age which Methuselah succeeded in reaching was probably due to the total absence of any Euphrates Chronicle or Mesopotamia Mail.

Another suggested a hydro with frequent baths; but would not the atmosphere of the place go far to modify the merits of the treatment?

Another counselled a sea voyage; but the prevalence of frightfulness on and under the ocean has made this a questionable scheme just now.

It was then that I chipped in. "I have discovered," I said, "a new and perfect kind of rest cure. It is simply this: to lend your house to nice friends and then to go and stay with them as a guest."

They asked me to amplify, and amplification being my long suit I gracefully complied.

The merits of the arrangement, I told them, should leap to the eye. To begin with you are at home, which is always more comfortable than an hotel or a hydro or anyone else's house. Hotels, to take one point only, disregarding their fussiness and restlessness and the demand made upon one to instruct foreigners in English, cannot cook or prepare the most important articles of food for those in need of repose—such things as bread and butter, boiled potatoes, mint sauce, horse-radish sauce (they often do no more than shred the horse radish and pour cream over it, the malefactors!), roly-poly jam pudding, bread-and-butter pudding, Yorkshire pudding. When it comes to grills, they can beat the private kitchen; but again and again the private kitchen beats them, and always in the essentials.

As for hydros, let us forget them, I said. And as for other people's houses, however comfortable they may be, they lie under the charge of being not your own. They have to be learned and there is not time to learn them. One is on one's best behaviour in them, and that is contrary to the highest restfulness.

One's own home, I went on, is not necessarily perfect; but quite a number of its drawbacks are removed when someone else is occupying and running it. Take the inevitable item of bills. Here my hearers all shuddered, and very rightly. Bills lose much of their minatory aspect when they are being paid by others. The disturbing thought as to the ruinous cost of butchers' meat which assails one directly the cover is removed no longer has any power to vex. The sirloin still represents too massive a pile of shillings, but the shillings are to come from other pockets—always a desirable state of affairs. Coal again. In one's own house normally one trembles, and particularly so just now, every time the poker is used; but in one's own house when one is a guest how blandly one stirs the embers into a richer glow.

Life can be made enormously more piquant in this way. Indeed it can really become worth living once more. One settles down in one's own well-tried chair; one looks round the room at one's own pictures and books; and all the time the coal that burns so fiercely and consolingly in one's own grate is being paid for by others. No stint either! Could there be a more delightful arrangement?

The disabilities of the scheme are trifling. It is, of course, a bore to find that one's private bath-time has fallen to the temporary owner, or that lunch is now half-an-hour earlier; but these are nothing. The great thing is that one is a guest here at last—that after years of striving to make both ends meet and having all the anxiety on one's own shoulders, suddenly it has gone; and when, instead of the modest claret which is all that one's own cellar can normally be induced to disgorge, however one may search it, the new occupants are found to be in allegiance to "The Widow," the rest-cure is made complete. Here, one says, is the solution. Now will I be reposeful indeed.

"That is my discovery," I concluded. "I made it a few weeks ago and I shall never forget it. All that one has to be careful about is the choice of friends to whom to lend the house."

"But supposing," someone asked, "they don't invite you to stay with them—what then?"

"That," I said, "would be awkward, of course. In fact it would ruin everything. But one must be clever and work it."

"How did you get your invitation?" another inquired.

"If you'll borrow my house, I'll show you," I said.

"A few days after we saw some deserters come in from the desert."

Daily Dispatch.

Native troops, we presume.

"The Kronprinz Wilhelm risks interment."

Daily News.

If the Crown Prince gets killed many more times he will not only risk it but get it.

"Stolen or strayed, from 51, Port-Dundas Road, Scotch terrier, answers to Mysie; if found in anyone's possession will be soverely dealt with."—Glasgow Citizen.

Poor Mysie may well say, "Save me from my friends!"

"Andler having explained the decifision to Leben, who knows English imperfectly, the prisoners then bowed to the magistrates and returned to the cells."

Liverpool Daily Post.

Andler must have found his gift of tongues severely taxed.