Page:Punch Vol 148.djvu/344

knew all about bloodhounds with chickens, Jimmy says, but his slippers wouldn't let him; they hadn't any heels and kept coming off in the soil. Jimmy says the man went on talking to himself over his slippers and looking for something to throw. But there were only the snowdrops, so he wont to the coalhouse as fast as his slippers could go.

Jimmy says the man wasn't a very good aimer, although Faithful gave him every chance. Faithful kept fetching the coal back for the man and then putting the chicken up again, but the man didn't hit the chicken once. Jimmy says the man had just emptied a little heap of gravel out of his slippers that he had forgotten about for the moment and was taking a very good look at Faithful when the man's wife came out and began to talk to him from the doorstep.

She said his name was Alexander and that he had to come in―did he hear her?―with coal at 30s. a ton. But the man had reached out too quickly to stroke old Faithful with his foot, and Faithful was busy trying to make the man's slipper growl at him in one corner of the lawn. Jimmy says the man is a good hopper, you could tell that from where he left his slipper when he did it. It was like swimming with one foot on the bottom, the way the man did it, Jimmy says, and when Faithful saw the man beginning to do that at him he couldn't bear it and went away. Jimmy says bloodhounds are like that, it unhinges them.

The man told Jimmy of a scheme he had for his bloodhound. It would make him look like a sieve, he said. He said Jimmy's bloodhound was an animal.

All this took up time and made Faithful quite late on the trail, and Jimmy was afraid his bloodhound would be too unnerved for really fine work. However, he led him up to the sausage shop, where he caught his first spy, and loosed him there.

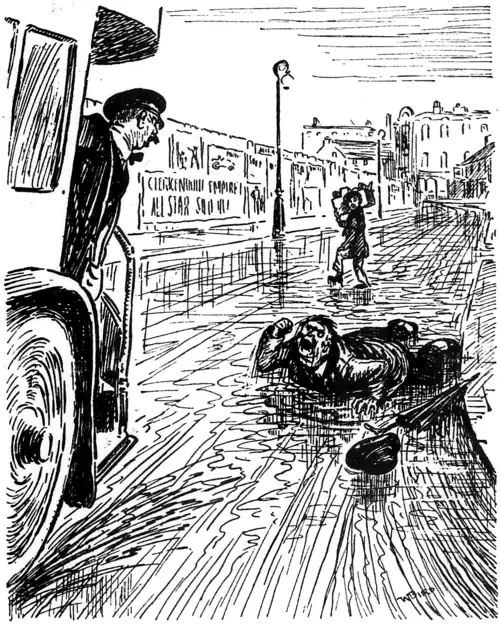

Faithful cast about for a little, scratched himself, then suddenly dashed into the shop hot upon the scent of another of those sausages with the red husk. He couldn't reach those in the window, so he went behind the counter and picked up the trail of one that must have been hiding under a glass dish. Jimmy heard the glass dish smash in the struggle. So did the man. He came running into the shop and threw a chopper for Faithful to fetch. Jimmy says the man got very excited and drew a revolver and fired at Faithful, and then shouted, "Mad dog! Mad dog!" as hard as he could.

Jimmy says that people were looking everywhere for the mad dog, and he was glad he hadn't fixed that sign the milkman told him of on to Faithful.

They had to tear the sausage from Faithful's mouth because his fangs were locked. The policeman was surprised at the sausage, Jimmy says; he said it was a wolf in sheep's clothing. That was because it contained a bundle of new bank-notes, done up in oilskin, instead of proper sausage dough.

Jimmy said it was a fraud, and the policeman said the banknotes were also, he thought. But he was so pleased with Jimmy that he played him a tune on his whistle.

Faithful followed all the policemen into the shop―you see he had tasted blood―and while the policemen went to talk to the man he kept the sausages at bay. He rustled them about a good deal, Jimmy says, and kept daring them to bite back at him.

Jimmy says his bloodhound got so exhausted with his work that he soon had only strength enough to lie down near a pork pie and place his tongue against it

It was not the same kind of spy as the other one Jimmy's bloodhound tracked down; it was a naturalised one.

Jimmy says they used Faithful as a bit of evidence, and the policeman had to swear he was a dog within the meaning of the Act.

Jimmy says the man made banknotes as well as sausages―better, the magistrate said. The man didn't want people to know he made bank-notes, so he put them in a sausage skin, and another man used to come and take them away. He was a confederate, like you have when you do tricks, Jimmy says.

The man kept the bank-note sausages under a glass dish so that they wouldn't stray away and mingle with the others.

The magistrate said that you couldn't always tell sausages by their overcoats. Some of them were whited sepulchres. The bank-notes were for a fund to aid German spies, and so they couldn't be sent by post, as the letters might be opened and the bank-notes leak out.

The man who used to come for the bank-note sausages has not been caught yet―he is still at large; but then so is old Faithful, Jimmy says.

"You started before I was ready. I'll have the law of you for this!"

"Now then, old submarine―none of yer frightfulness!"

In a recent issue we quoted the order issued at an Indian camp that "any Volunteer improbably dressed will be arrested." Judging by the following extract it would appear about time that the military authorities at home took similar action:―

"The greater portion were clad in khaki, some were in blue, whilst others wore semi-military dress. A section of the men wore greatcoats and ordinary caps―one man had donned a Trilby and another a felt hat, while a Morecambe company wore mittens."―Daily Dispatch.

In Scotland things are even worse, for we read in the prospectus of a certain Volunteer Training Corps that―

"It is proposed that the only uniform to be worn to begin with shall be a Hat (conform to Regulations) and a Brassard to be worn on the left arm."

FLOREAT ETONA.

Where Justice falters at a fear of Hate.

Our Head may plead, "Oh, humble not the Hun!"

Our speech is with the Enemy in the Gate.