Page:Punch Vol 148.djvu/340

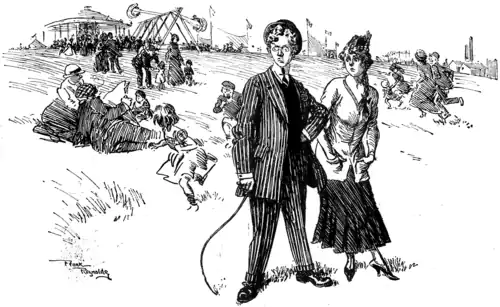

She. "Look here, George, I'm going 'ome if you're going to talk about the War all the time! If you feel so pent-up, why don't you go an' 'ave a shy at the coker-nuts?"

MANY A SLIP.

I think I have mentioned Jessie as a champion cup-crasher before. There are people who can drop cups and glasses without breaking them. Jessie can break them without dropping them. It is a gift, and she has it. She has other gifts, including that of kindness to Peter, and these have prevented our side-tracking her so far.

Alison has tried to cure her by threats of dismissal, but threats only encourage Jessie to higher flights of smashing. She knows by now the low breaking strain of vegetable dishes to an ounce, yet in her daily intercourse with these utensils she cheerfully subjects them to such stress as would shatter a brick. With cups and saucers I think she must practise secret jugglery in the pantry.

Every month-end, or nearly so, after Alison has paid her wages, she says, "Jessie really will have to go; two more plates broken and another badly cracked;" or "The handle has been knocked off the Lowestoft jug; Jessie says she was dusting it, and it simply dropped off;" or "Poor Aunt Emily's present [a Dresden group] has lost an arm."

Last Saturday night I felt that the climax had been more than reached. Peter found the base of our only Venetian glass vase, the pride of the combined family heart, under the drawing-room sofa. The rest of it had disappeared into the dust-bin.

I traced in the air the letters J.M.G. Alison asked what I meant.

"Jessie Must Go," I said impressively, "before she makes another raid on our unfortified crockery."

"I suppose so," said Alison wearily. "But really I don't know where I shall find another maid like her."

"I don't want you to find another like her," I said. "I want you to find someone as unlike her as possible. She's an image-breaker, an iconoclast. I begin to suspect her of being of German extraction. Give the girl an Iron Cross and let her go."

"You forget," said Alison, "that she is simply invaluable with Peter."

"True," I said, "she is kind to children. Well, she shall have one more chance."

*****

Sunday passed off quietly. Jessie spent her spare time knitting socks for soldiers. My witticism about her breaking the Sabbath was not so well received as I thought it deserved.

On Monday evening when I arrived home, Alison looked so down in the mouth that I felt sure there had been another breakage, a bad one, and I was right.

"Let her have her passports at once," I said, "for goodness' sake. She's breaking up the happy home on the instalment plan."

"No," said Alison firmly, "I can't give her notice this time."

"Then come and watch me do it," I said. "What's she broken?"

"It's rather a nasty breakage, too," said Alison.

"Come," I said, "out with it. Not any of the Chinese dessert service on the dresser; not the———"

"No," said Alison, "she was saving Peter from falling downstairs and—"

"Well," I said.

"She slipped," said Alison, "and broke her collar-bone."

*****

And now Jessie is a heroine, and when she returns from hospital with the medal for personal bravery she will be firmly established for ever in our household, with licence to break whatever she chooses.

"The use of steel for the making of guns was begun by Alfred Krupp, the master of Essen, probably the ablest metallurgist that the world has ever seen. He died long ago, and Sheffield knows many of the secrets that died with him."—Glasgow Evening Times.

These dead secrets always somehow get about.