Page:Punch Vol 148.djvu/285

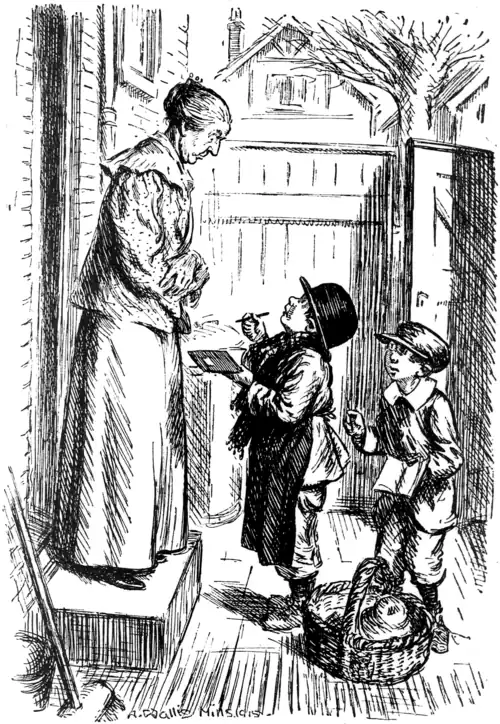

THE SHORTAGE OF MEN.

"Now then! what do you little boys want?"

"'E's ver baker, 'n' I'm ver burcher. An' we've come for orders."

PORTSMOUTH BELLS.

Right through the Harbour mouth,

Where grey and silent, half asleep,

The lords of all the oceans keep,

West, East, and North and South.

The Summer sun spun cloth of gold

Upon the twinkling sea,

And little t.b.d.'s lay close,

Stern near to stern and nose to nose,

And slumbered peacefully.

Oh, bells of Portsmouth Town

Oh, bells of Portsmouth Town

You rang of peace upon the seas

Before the leaves turned brown.

Beyond the boom to-day;

The Harbour is a cold, clear space,

For far beyond the Solent's race

The grey-flanked cruisers play.

For it's oh! the long, long night up North,

The sullen twilit day,

Where Portsmouth men cruise up and down,

And all alone in Portsmouth Town

Are women left to pray.

Oh, bells of Portsmouth Town,

Oh, bells of Portsmouth Town,

What will ye ring when once again

The green leaves turn to brown?

BÈTES NOIRES.

We were indulging in one of the minor—or possibly major—pleasures of life. We were discussing the kind of people we most disliked. I don't mean the real criminals, such as those cabinet makers who construct, and those furniture-dealers who sell, chests of drawers in which the drawers stick. They are miscreants for whom there should be government machinery of punishment. I mean the people who mean well—always a poisonous class—but irritate subtly and in such a way that you can't hit back: the people, for example, who take one of your own pet stories, begin to tell it to you and won't stop even when you say that you know it. People like that, and people who are so polite that they make ordinary decent manners appear brutish by contrast; and people who continually ask you if you know such and such a celebrity and seem shocked if you don't; and people who want to know if you are doing anything on Friday fortnight; and people who could have done such and such a thing for you if you had only asked them three minutes sooner.

Those are the kind of people I mean, and we had each named one variety when it came to the Traveller's turn.

"I'll tell you the people I most dislike," he said. "They are the people who have always seen, in foreign places, the best thing of all, and it is always something that you yourself have missed. You are comparing notes, say, on Italy (it is usually Italy, by the way). 'Of course you went to Castel Petrarca,' says your companion. 'No.' 'Why, it's perfectly wonderful and only half-an-hour's drive. There's the most exquisite view there in the world and a villa overlooking the river, with a garden—well, all other gardens are ridiculous ever after: even that jewel of a place near Savenna. You know—on the right of the road as you drive out to Acqua Forte.'"

He paused for breath and then continued: "Or you are talking of pictures—the work, say, of Binatello of Porli, that little known but supreme master. 'Of course' (they always begin with 'of course')—'of course you have seen the Annunciation in the little chapel at Branca Secca?' you are asked. 'No! But how appalling! You too!—to think of you missing it, of all people!' (This is a particularly horrid stab). 'Why, it's the best thing of all; it's Binatello at his very finest. It has all the charm of the Parmosan Madonna, with the broader, stronger manner of the Orefico Deposition added. It's marvellous. Fancy you not seeing that. Well, I am sorry.'

"Those are the people I most dislike," said the Traveller.