Page:Punch Vol 148.djvu/223

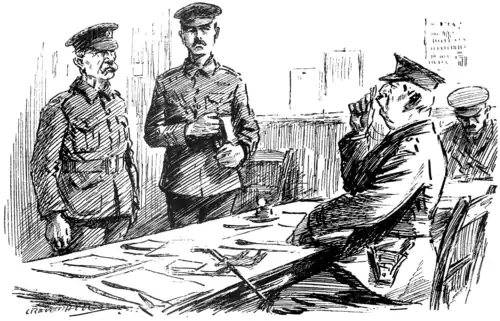

C.O. (to delinquent brought up for having a dirty rifle). "Ah! a very old soldier! I suppose you made yourself out to be years younger than you are when you re-enlisted. Well, what were you charged with the last time you were brought up to the orderly-room?"

Delinquent (stung to irony). "'Avin' a dirty bow-an'-arrer, Sir!"

MEANS OF COMMUNICATION.

The offices I have just taken are very convenient.

I can sit in the inner sanctum and, by leaving the connecting door slightly ajar, can see right through to the outer door, and observe incomers before they have time to spot me. To a man starting without a clientèle this is extremely useful. It does not look well to be caught lolling back in one's arm-chair reading light literature at, say, 11.30 A.M., especially if one's feet are on one's writing-table.

When my typist is in the outer office of course I can throw precautions to the winds.

I only moved in last Wednesday, and if I happen to be alone and hear or see the outer door open I usually spring to attention and bring the telephone receiver smartly to my loft car, keeping the right ear and both eyes trained on the incomer.

Generally it is the typist coming in from lunch, or from the bank, or from wherever typists go for employers who are without business; but yesterday I received a shock. I was deeply engrossed in Blank's Monthly when a knock came at the outer door. I called out, "Come in," dropped the magazine into the waste-paper basket, and, taking the receiver off the hook laid it noisily on the table, then, putting my head round the connecting door, I said, "Please excuse me one moment. I'm talking to someone on the 'phone. Most important."

I had a fleeting glance of a man before I rushed back to the receiver, a man with a small black bag such as some solicitors wear. I motioned to him to be seated, and left the door ajar so that my visitor should not miss hearing anything that might be instructive from the inner office.

I disregarded the appeals of the telephone operator. "Please repeat that, Sir Robert," I said to the instrument. "I was called away for a moment by another client. Ah, yes, quite so. But I think you had better make up your mind. The duchess is after the property too. Yes, seven, fourteen or twenty-one years. Oh yes, the drains are in perfect order. Only stabling for six, I'm afraid. Well, yes. We have another in Hampshire. Don't like Hampshire? Well, let me think. Ah, of course, the very thing. Sir Carl Umptyum (I am afraid it sounded like that) has just put his place in our hands. Well, he finds the East Coast a little too warm just now. Oh, yes, stabling for thirty. Four greenhouses on cement foundations and—what? Yes, I'll have all particulars sent on to you by this post. Oh, certainly. Good-bye."

I hung up the receiver and throw open the connecting door. "I'm very sorry," I said, "to have kept you so long. Please come in."

Instead of speaking, my visitor handed me a piece of paper on which I read:—

"I am deaf and dumb; please help me by purchasing a typewriter ribbon or some ink-eraser."

The Literal Teuton.

Translation of extract from the Prager Tagblatt:—

"That at the present time acquaintance with the German language is none too widespread is plainly demonstrated by the issue of Punch for December 23rd, 1914. Here the German Crown Prince writes to his Father in an 'Unwritten Letter': 'Do not imagine that I am pulling your leg,' which is absurdly rendered: dass ich dir das Bein ziche. It is equally unintelligible when the Crown Prince expresses the fear: dass wir es überall in dem Hals kriegen."

Aren't they hopeless?