Page:Punch Vol 148.djvu/161

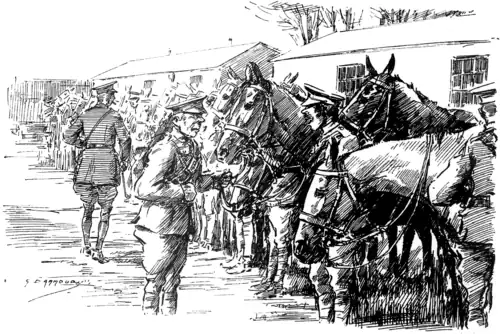

Recruit (who had given his age as 33 on enlistment). "Did you 'ear that? Told me my bridle wasn't put on right! Bless 'is bloomin' innocence! And me bin in a racin' stable for the last five-and-thirty year!"

A TERRITORIAL IN INDIA.

IV.

My dear Mr. Punch,—In case you formed any mental pictures of my first Christmas as a Territorial in India, let me hasten to assure you that every single one of them was wrong. I neither took part in the uproarious festivities of the Barracks nor shared the more dignified rejoicings of the Staff Office in which I am condemned for a time to waste my military talents. An unexpected five days' holiday, and a still more unexpected windfall of Rs. 4 as a Christmas Box (fabulous gift for an impecunious private) enabled me to pay a visit to some relatives, who live at, well ———. One has to be careful. The Germans are getting desperate, and they would give worlds to know exactly where I am.

——— is a place rich in historical interest and scenic beauties. Freed from the rigid bonds of military discipline and the still more hampering restrictions of official routine, I was at liberty to enjoy them to the full. It was the opportunity of a lifetime to see something of the real India. Did I take it? No, Mr. Punch, to be honest, I did not.

After hundreds of years (so it seems) of Army active service rations, of greasy mess tins and enamelled iron mugs, I found myself suddenly confronted by civilised food waiting to be eaten in a civilised fashion. And I fell. Starting with chota hazri at 7 A.M., I ate steadily every day till midnight. That is how I spent my holiday. I may as well complete this shameful confession; it was the best time I ever had in my life.

I feel confident that my stomachic feats will never be forgotten in ———. I shouldn't be surprised if in years to come the natives are found worshipping a tree trunk or stone monolith rudely carved into the semblance of an obese Territorial. It is pleasant to think that one may even have founded a new religion.

But I am grieved and troubled about one thing. I ate plantains and guavas and sweet limes and Cape gooseberries and pomolos and numberless other Indian fruits (O bliss!), but not custard apples. Custard apples, it appears, are the best of all, and they went out of season just before I arrived in India and will not come into season again for months and months.

I am confident that you will appreciate my predicament. I want the War to finish quickly, but I want to eat custard apples. I want to get to the Front and have a go at the Germans, but I desire passionately to eat custard apples. I want to get home again to you, but after all I have heard about them I feel that my life will have been lived in vain if I do not eat custard apples. It is a trying position.

Home was very much in my thoughts at Christmas time. The fact of having relatives around me, the plum pudding, the mince pies, the mistletoe, the clean plates, the china cups and saucers, the crackers, the cushions, the absence of stew,—all these and many other circumstances served to remind me vividly of the old life in England. And when regretfully I left ——— and (like a true soldier cheerfully running desperate risks) travelled back in a first-class carriage with a third-class ticket, I found at the Office yet another reminder of home and the old days. My kindly colleagues had determined that I should not feel I was in a strange land amid alien customs. They had let all the work accumulate while I was away and had it waiting for me in a vast pile on my return.

That is why this is such a short letter.

Yours ever,

One of the Punch Brigade.